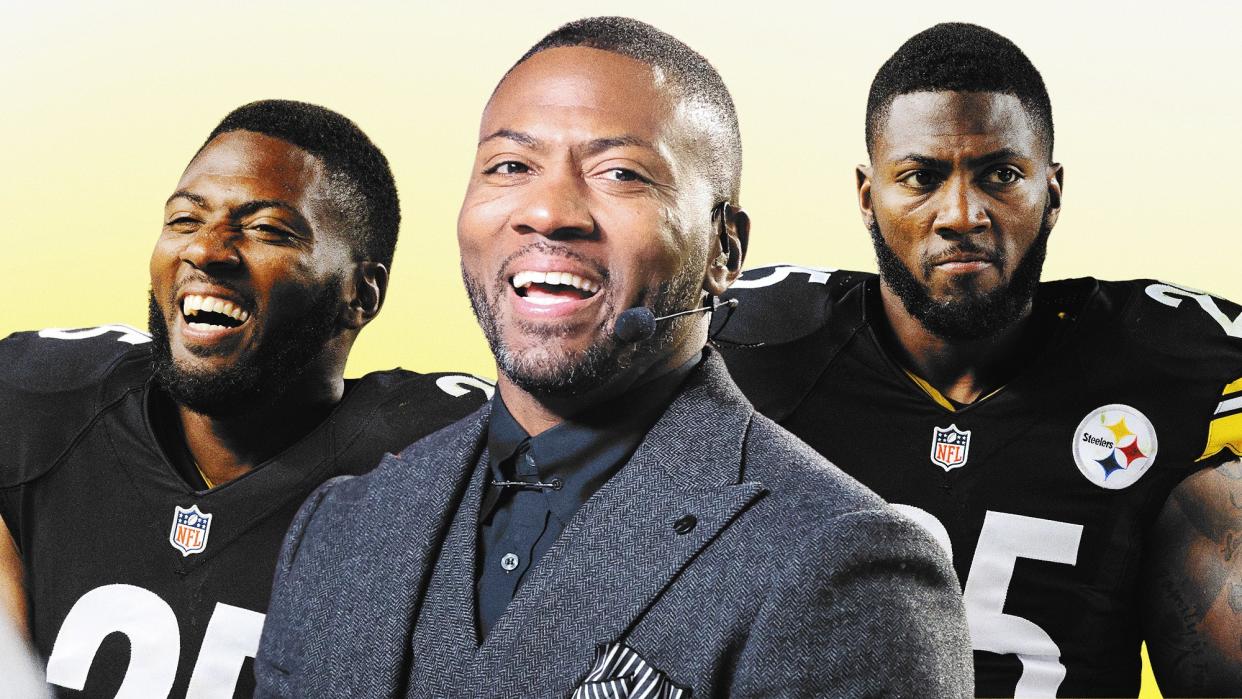

Ryan Clark Is as Good as Football Media Gets. He's Still Not Sure TV Is for Him

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Photographs: Getty Images; Collage: Gabe Conte

During his 13 years playing safety in the NFL, Ryan Clark’s primary concern was fortifying the backend of the defense, sometimes by any means necessary. “I didn’t care who liked me then,” Clark, 44, tells me with a laugh. “I wanted the other team to be like: ‘That dude’s dirty.’” But in the similarly cutthroat and results-driven sports media industrial complex, where Clark began working as an active player, he understands the necessity of broad appeal.

The Pro Bowler and Super Bowl champion brings candor and acuity to various ESPN programs, from Get Up to SportsCenter with Scott Van Pelt. He hosts the ESPN podcast DC & RC with UFC legend Daniel Cormier, as well as The Pivot with fellow former NFL players Fred Taylor and Channing Crowder. This fall, he became the host of a revamped Inside the NFL, which has relocated to the CW, leading a panel featuring Crowder, Chad Johnson, Chris Long, and Jay Cutler.

Inspired by the late Stuart Scott, Clark has a knack for weaving pop culture references into his analysis to engage viewers who perhaps aren’t as familiar with concepts like 12 personnel and light boxes. Flair aside, Clark’s work stands out due to a clear-headed perceptiveness shaped by his time in the league. That was strikingly evident during Week 17 of the 2022 NFL season, when Buffalo Bills safety Damar Hamlin’s heart stopped during a Monday Night Football game.

Sitting across from Van Pelt, an emotional Clark delivered thoughtful and compassionate commentary—extending support to Hamlin, his family, and everyone on the field with him, while also putting the human aspect of the moment into perspective for the millions of viewers watching from a distance. As always, Clark’s words were colored by his experience. Clark, who has sickle cell trait, missed most of the 2007 season after suffering a near-fatal splenic infarction due to the altitude at Denver’s Mile High Stadium.

Clark’s handling of Hamlin’s injury has become a defining moment of his broadcasting career. Earlier this year, he won a Sports Emmy for Outstanding Personality/Studio Analyst. “I meet people all the time who I know don’t watch sports, but they tell me: ‘You’re so great on TV,’” he says. “And they actually don’t know how good I am on TV, they just know how good I was that night.”

Someday, Clark hopes to spin his cross-platform success into a general manager position. Ahead of his alma mater LSU’s annual face-off against Alabama last month, Clark discussed his front office aspirations, the adjustment to hosting a TV show, how he handles being wrong within the unforgiving take economy, and more.

Not every former athlete is good on TV. What did you realize you needed to do to stand out, and has that evolved?

The first year, I just wanted to let people know that I wasn’t a dummy. I wasn’t a household name, I didn’t play quarterback—and honestly, being African-American, I knew people probably thought I was stupid. I’m from New Orleans; I talk a certain way. They were sending me to dialect coaches, and I was doing it and watching footage of people on TV, but eventually I realized there’s no way I was going out-Hasselbeck a Hasselbeck. How am I going to out-Riddick a Louis Riddick? But they also can’t out-Ryan Clark me.

I was walking down the hall with a colleague who covered me when I played. She thought I was really funny and she said she wished other people knew that, because I was so serious on TV. And I was serious because I didn’t want to be thought of as a fool. It was almost the fear of letting people know who I am, because then they get to reject that. You can’t reject these facts and this film, so it was just a matter of relaxing and learning how to be me in a way that felt authentic, but then entertaining and informative enough to reach people.

It was probably around the time that Get Up started, because the show was so awful at first that they had to lean on the talent. That’s when Dan became the touch-screen guy. It’s when the world actually met “Swagu” [Marcus Spears’ nickname]. Once you start being that person on Get Up, now First Take and SportsCenter want it. I tell people all the time: for me, at least analyst-wise, that show might not be the most popular, but it’s the star-maker.

Which analysts were you a fan of before you got into the business and why?

To be honest, I was a big Tom Jackson fan. Everybody watched NFL Primetime and NFL Countdown, and the dude was always so poised. It felt like he never said anything wrong. I was also a huge Stuart Scott fan. His ability to run the entire show, entertain, analyze, provide opinion but also humanize is, to this day, second to none. As I started to understand analysis, that’s why I wanted to host. I haven’t gotten anywhere near that yet, or being completely comfortable being me, because that’s what I loved about Stu: he was comfortable being him.

He opened the door for the way I do TV. I love music, movies, and culture, and I feel like others do too, so I think those references help people who may not understand what I’m trying to explain about the run game connect to sports because they understand how awful a movie The Shape of Water is. They may not understand what Jordan Addison creating 2.3 yards of separation is, or how he was able to run away on this dig, but they do understand how Jada Pinkett-Smith runs away from her marital responsibilities. They’re current events that give people a chuckle.

You’re also able to bring the proper amount of gravity to a situation when necessary. For example, when Damar Hamlin collapsed last season, which had to bring back memories of what happened to you in 2007. Was it even possible to separate that experience from the moment, focus on Damar Hamlin, consider how it affected everyone who watched it happen, then deliver something so coherent and empathetic?

I truly don’t mean to say this arrogantly, but who was better for it? We just did an episode of The Pivot with Ed Reed, who lost his brother. Ed lets a lot just roll off his back, but when he was talking about that experience, he said: “I didn’t know it when I was going through it, but I walked into work one day and Torrey Smith was crying because his brother had just died. And I was able to share my experience and empathize with him.” Don’t get me wrong: I didn’t go through what I went through so I could be ready for that moment. But I didn’t separate it. That’s why I was able to do it.

My situation was different because it didn’t happen on the field. I went to the hospital on Friday, they played Cleveland on Sunday and lost. Troy [Polamalu], who’s Greek Orthodox Christian, came to my room and brought me some of his prayer idols. He brought me a bible and we just cried for hours, because at that moment, he’s looking at his best friend in the world—who, a month before, was 205 pounds and is now 160. I’m crying, because I can see how scared he is. And since I’d been going through it daily, I already knew what it was.

So when I’m looking at Stefon Diggs and Tre’Davious White crying, I know that look. The majority of the people who do my job don’t. They don’t know what it’s like when someone tells you they don’t know if you’re going to live, and then when you do, they don’t know if you’re ever going to play again—but you do. So you take a deep breath, pray about it, and ask God to guide your thoughts and words. I just gave the people me, and in giving them me, I think I was able to give them a glimpse into what Damar and the team were dealing with.

Did you talk to any of your former teammates immediately after that?

Everybody hit me up, but we didn’t really talk about me. We’re so far removed from that, and honestly, we didn’t live in it. As soon as I could get out of the hospital and they cleared me, I started going to games. They made fun of me because my clothes were too big, but you also have to remember that as soon as I got out of the hospital, Sean Taylor died. He was one of my best friends, so how could I sulk?

Discerning viewers know that ESPN is an entertainment vehicle. How do you balance the occasional ridiculousness with actual insight?

It’s hard, bro. Because those entertainment levels are what get you noticed, but then there are going to be people who critique the meat of what you say. And I do think you have to be able to do both, or you become a dinosaur. Because if you lean too hard into the entertainment part, you become a caricature. And if that’s what you’re comfortable with, then fine. But people are going to want to hear the truth about certain things, so you’ve got to be able to bring that, just for that credibility.

My truth is more about how the locker room of it all relates to me. I don’t care about fans. Every fan hates you when you don’t say something good about their team, so I can’t win with them. But if the players rock with you, that matters. So for me, being able to walk into any locker room and have people tell me they love what I do, they relate to me, or I inspire them? That’s what matters to me. The rest of it is what it is. But I think you do it based on the show and the topics. I feel like I’ve got to be different on every show that I’m on. To your point, here’s what I get all the time: “I like you so much more on The Pivot than I do on TV.” Which I respect, because I get it, but it’s two different platforms. I’m both people, right? I’m just paid to do different things on each platform.

Yes, I’m probably more likable when Michael Beasley is crying, I’m crying with him, and I’m trying to encourage him. I would like me more then, too, as opposed to when I’m talking about how many interceptions Josh Allen threw. So I had to remove the personal feelings of wanting people to understand or like me and just do the job to the best of my ability.

To your point, it’s not easy trying to come up with compelling ways to discuss the biggest stories in sports every day. But people do look to former athletes for their expertise. How do you avoid “take brain,” where people go off the deep end while trying too hard to make “good” television?

It’s hard. I think I’ve maintained it because I don’t know what makes good television for everybody else, but I know what I feel good about. Sometimes I hear it, sometimes I don’t. Sometimes, I’m like, “Yeah, I didn’t love that.” The harder part, for me, is that by the time I do NFL Live at 4 p.m., I’ve already done three shows and I’m being asked the same things. And I know that not everyone watches all three shows, but I get tired of saying it the same way. So then you try to think about how to make the same analysis intriguing, which I think is harder than trying to make great TV. It’s trying not to make the same TV, over and over again.

You also run the risk of being wrong and getting called out for it. I think athletes, especially football players due to the size of the rosters and the general precarity around the contracts, really understand the concept of accountability. Being called out when you’re wrong is being held accountable. How do you deal with that?

Regarding game predictions, I don’t care. You are wrong on those shows a lot of the time, because they’re asking for so much prediction. I’ve always hated: “Who’s going to have the bigger game?” I don’t know—that’s why they play the game. “Who’s under more pressure?” I don’t know—ask them. I love NFL Live because we can decide what we want to talk about within the matchup of the Chiefs defense and the Dolphins offense: do you want to talk run game or do you want to talk stopping Tyreek? Now I’m giving you an Xs and Os take that is: “I think these things need to be done, and if they’re done well, this team can be successful.” I’m never wrong on that because it’s based in film.

But yeah, if you ask me who I trust more between Lamar Jackson and Jared Goff, when Goff has 28 touchdowns and four interceptions in the last however many games and Lamar is coming off his receivers dropping eight passes, of course I’m gonna pick Goff. But that doesn’t mean Lamar Jackson can’t play out of his mind and Jared Goff can’t have a stinker of a day. I can’t control that. And then the fans try to come at you like, “Yeah, you’re stupid”—no I’m not, that’s just how the game went.

As a former player, how mindful are you of how you critique current players?

That’s also hard, because when you get on those shows and just start talking, it can go left quickly. I try to root everything in film, study, and what I consider to be fact. I think if you can do it that way, you win. But people don’t always do that. I’ve also had to learn that social media counts, not only in terms of your initial thought, but the follow-ups when you’re responding to people who disagree.

For example, I met Keenan Allen for the first time when the Cowboys played the Chargers and I apologized to him. I apologized, because one day I was looking at top receivers [from a given year]. There were like, five receivers who had outstanding seasons, and someone asked who you’d want out of them. Somebody said Keenan Allen, and in that particular season, his stats and impact, compared to those guys, wasn’t the same. But on third down, Keenan Allen had the most catches of everybody in the league. It was during the offseason, I was bored, I just wanted to get some interaction, but I was like, “Nah, Keenan Allen wasn’t like these dudes this year.” Then everyone from the Chargers chimed in, and I reiterated that those receivers were the best five. He said something and I was like, “Fam, not in this conversation.”

It didn’t get ugly, but I was wrong and accountability is important to me. He didn’t hold a grudge, but I let him know that I had to clear that up. Even the joke I made about Tua—which was really just a joke to me. You don’t know how many oldheads and former players called me busting out laughing or texted me like, “Dog, I know what you were saying.” And it turned out that he purposely added weight to his lower half, but I was just telling a joke that I would tell if you and I were talking. But you have to realize that the way people digest and comprehend things is your responsibility as well. So I apologized because I didn’t mean it like that.

This year you started hosting Inside the NFL. What are some of the new responsibilities you’ve had to shoulder?

I think that’s the cool part. Being an analyst is boring [laughs]—and I’m in no way saying that to be negative. It’s just what I’ve always done, that’s how I started out in this business. But that’s evolved. I’m the only person who’s on-camera who’s in this Friday Zoom meeting I just got off of with directors, producers, graphics people, social people, the vice president. I’m the one who says, “No, I feel like this works” or “We should try this segment.” I’m pitching segment ideas, saying: “Chris [Long] would be perfect here” or “This is where Jay [Cutler] could be phenomenal” or “We need to figure out how to get Channing or Chad [Johnson] involved.” That’s everything I love.

When you look at my career, that’s how I made it. I didn’t make it because I was this talented dude that got drafted in the first round. I made it because I could tell Troy where it was best for him to be. I could tell James Harrison, “Hey, this is what’s coming. Rush now.” I could tell James Farrior, “While you’re doing the cross dog [blitz], the center’s going to lead to you.” That’s what I love to do and it’s what I do now. When I get there, I'm the only talent in the first meeting. When we get to the pre-production meeting where we’re watching the videos, it’s: Chris, what do you think about this? OK, you like that? You go first. Jay, you just come off of Chris, I’m not going to re-tee you.

What’s different about this, as opposed to ESPN, is that I’m getting to do a lot of what producers do in setting this show up. And I love the feeling of, “Oh, this conversation’s great. Let’s keep it going. Or, “Chad has something—go, Chad.” Getting to be a captain is cool, but they didn’t give me that trophy last year because they thought I might be a good host one day. They gave it to me because they thought I was one of the best analysts in the world. The hardest part is making sure that I can still do that on this show.

I was watching the episode of The Pivot with Mike McDaniel. You talked about the influx of younger head coaches in the NFL. I imagine it’s quite different for you to see guys who are roughly your age, and sometimes younger, taking the reins when Jim Fassel was your first coach.

Bro, Joe Gibbs was my second coach.

Then you got some of Bill Cowher.

In our Sean McVay episode, he talked about the end of my last season in football, because he was the offensive coordinator in Washington. I would just go into his office and chop it up on Monday. I didn’t play for him, so that was cool, but we talked ball, life, and leadership. I knew then that he’d be where he is now. I wasn’t walking into his office because of that—I think I just walked by his office and we started asking each other questions. I think the brightest minds in football, at the executive level, are starting to realize that it doesn’t have to look or sound a certain way. And when you look at what we’ve been asking from the minority head coaching hires, it’s sort of similar.

It used to look like Bill Belichick and Nick Saban. Now, it can look like Mike McDaniel. But it also happens when the “normal” doesn’t work every time. When it feels like Josh McDaniels should work, but it hasn’t—twice. And then the players go to you, as in Mark Davis, and say, “No, we want Antonio Pierce as the interim.” No coordinating experience in the league. No head coaching experience on any level but high school. But they wanted him because they relate to him. And as the media has become more player-driven, I believe executives and owners are starting to realize that coaching is, too. The ability to relate to and communicate with players is probably more important than how many times you can tell me to get to the middle of the field.

There’s been a recent decline in offensive production across the league. What do you think factors into that?

Here’s what I’ll say: development has changed. With seven-on-seven, these kids get so many pass play reps, both offensively and defensively. The problem is that offensively, they’re dialing back the knowledge and diversity. We’re gonna throw screens; we’re gonna throw you a go ball. We’re not teaching you the route tree. But defensively, you’re getting all these opportunities to see the quarterback and play the ball, so now we’re seeing how talented these DBs can become.

What’s also happening, in terms of defensive linemen, is now there’s all these incredible athletes. But because they don’t do enough in high school and college, offensive linemen aren’t developing like that. So it’s really just how development has happened, so now I feel like those defensive players are so far ahead, from a talent, development, and work level, that they dominate. And it’s fun to watch those individual matchups, but we’re also seeing what happens when people are freakishly talented. Tyreek [Hill]? Freakishly talented; nothing you can do. AJ Brown? Freakishly talented; nothing you can do. Ja’Marr [Chase], too.

You want to know some of the strange outliers? Justin Jefferson. Davante Adams. It’s almost like when a girl falls for a guy but she doesn’t know why. These guys just do the right things: master their craft and compete.

Was there ever a period of post-retirement existential drift where you wondered, even briefly, what was next for you?

I don’t love TV, so yeah, all the time. And you have to realize: I started working in 2013. I’m the first active player to have a TV contract, which seems like forever ago because now everyone has a podcast. For me, it was, “Oh my God, I can’t believe you’re going to work and play football” or “Isn’t that a problem?” All I’ve ever wanted to do is coach football. I’m probably never going to do that unless I do it in high school. But when I retired, my son was starting high school and told me he wanted to play college football. I told him I could help with that. So I just poured my life into my family and needed a job that would give me the flexibility to do that, and pursue certain passions. But there’s a lot of times where I’ve thought TV is not for me.

It’s a subjective, opinion-based business, both in the way you do it and the way you’re critiqued. One person might think I’m excellent, but another might think I’m terrible, and those are the people making the decisions. But I’m going to be a GM one day; that’s my next job. I prepare every day by talking to former GMs, putting together my list of priorities, and writing down what sort of coach I want to work with. What alignments are necessary in order to go out and pick players. What’s the physicality level of my offense? How do I want to play defense?

When I watch college ball now, I don’t think, “Oh, this team is great.” I think, “This is the best quarterback, now let me watch him.” I looked at the draft and thought there were three guys, then a fourth. Those three guys went first, second, and fourth. I thought C.J. [Stroud] was the best of them, but Bryce [Young] went first, then C.J., then Anthony [Richardson], and I thought Will [Levis] was a little bit off from there. In that sense, I was right because people saw it like me. Now you watch Will play through two games and maybe he belongs in that conversation as well. So I file away how I evaluated him, because maybe it helps me get that job.

Originally Appeared on GQ