Russia Is Going to Try to Clone an Army of 3,000-Year-Old Scythian Warriors

Russia’s Defense Minister suggested he wants to clone a group of ancient warriors.

That’s going to be tricky. To date, there haven’t been any human clones, and the odds are low for even non-human clones.

The legality of cloning is murky because of the medical uses for specific kinds of cloning.

When you hold a job like Defense Minister of Russia, you presumably have to be bold and think outside the box to protect your country from enemy advances. And with his latest strategic idea—cloning an entire army of ancient warriors—Sergei Shoigu is certainly taking a big swing.

In an online session of the Russian Geographical Society last month, Shoigu, a close ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin, suggested using the DNA of 3,000-year-old Scythian warriors to potentially bring them back to life. Yes, really.

First, some background: The Scythian people, who originally came from modern-day Iran, were nomads who traveled around Eurasia between the 9th and 2nd centuries B.C., building a powerful empire that endured for several centuries before finally being phased out by competitors. Two decades ago, archaeologists uncovered the well-preserved remains of the soldiers in a kurgan, or burial mound, in the Tuva region of Siberia.

Because of Tuva’s position in southern Siberia, much of it is permafrost, meaning a form of soil or turf that always remains frozen. It’s here where the Scythian warrior saga grows complex, because the frozen soil preserves biological matter better than other kinds of ground. Russian defense minister Sergei Shoigu knows this better than anyone, because he’s from Tuva.

“Of course, we would like very much to find the organic matter and I believe you understand what would follow that,” Shoigu told the Russian Geographical Society. “It would be possible to make something of it, if not Dolly the Sheep. In general, it will be very interesting.”

Shoigu subtly suggested going through some kind of human cloning process. But is that even possible?

To date, no one has cloned a human being. But scientists have successfully executed the therapeutic cloning of individual kinds of cells and other specific gene-editing work, and of course, there are high-profile examples of cloning pretty complex animals. Earlier this year, for example, scientists cloned an endangered U.S. species for the first time: a black-footed ferret whose donor has been dead for more than 30 years.

So, why are humans still off the menu?

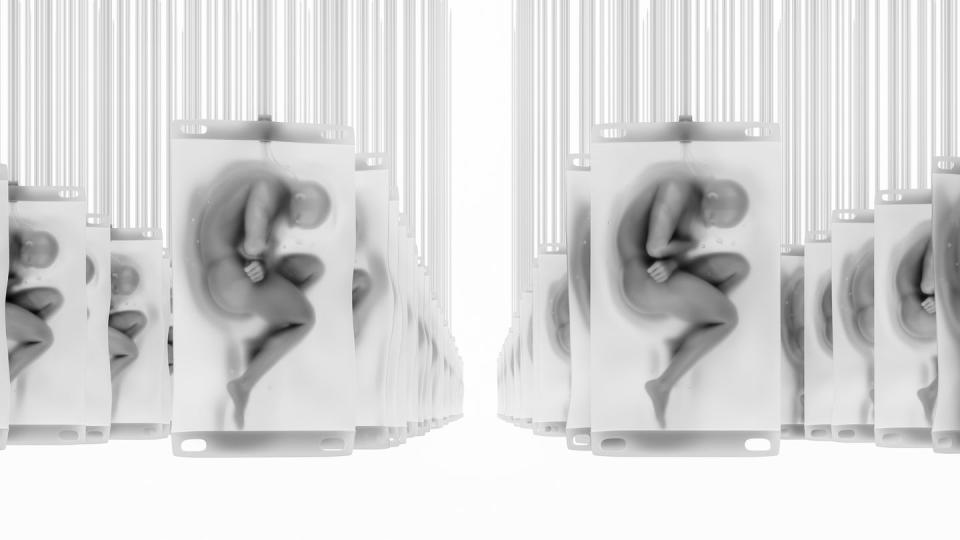

Blame a technical problem with the most common form of cloning, which is called nuclear transfer. In this process, a somatic cell (like a skin or organ cell, with a specific established purpose in the body) has its nucleus carefully lifted out, and this nucleus is deposited in an oocyte, or egg cell, with its nucleus carefully removed. It’s like a blank template waiting to have a new nucleus swapped in.

“From a technical perspective, cloning humans and other primates is more difficult than in other mammals,” the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) National Human Genome Research Institute says on its website:

“One reason is that two proteins essential to cell division, known as spindle proteins, are located very close to the chromosomes in primate eggs. Consequently, removal of the egg's nucleus to make room for the donor nucleus also removes the spindle proteins, interfering with cell division.”

You might remember spindle proteins from your mitosis diagrams back in high school biology. And while there’s a relatively easy way around this problem, it’s almost moot when cloning humans is considered extremely taboo in most of the world. In some places, it’s also explicitly illegal.

Curiously, the U.S. hasn’t banned the gene editing of embryos. But the NIH doesn’t fund research on the practice, and places like in-vitro clinics aren’t allowed to do any non-U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved manipulation of embryos under any circumstances.

That example starts to illustrate why the problem is so complex—because a lot of cutting-edge genetic medicine is walking right up to the line without crossing it. Making laws that address full human embryo cloning, then, requires a jigsaw puzzle of careful language that doesn’t rule out these kinds of therapeutic cloning.

But let’s say Russia ignores all legality in favor of Shoigu’s big plans. In that case, scientists would have to develop a way to lift out the human nucleus without damaging the cell beyond repair.

Scientists have cloned certain monkeys, so primates are at least hypothetically still in the mix, despite the spindle proteins. But the success rate even for non-primate clones is already very low—it took Dolly the sheep’s research team 277 attempts to get a viable embryo.

And what if all of that went perfectly? Well, the Scythians were powerful warriors and gifted horsemen, but scientists—or the Kremlin—must carefully monitor a cloned baby version of a deceased adult warrior for illnesses and other prosaic childhood problems. Who will raise these children? Who will be legally responsible for their wellbeing?

Shoigu may envision a future race of extremely capable fighters, but ... that’s at least 20 years away, with an added coin flip on nature versus nurture. After all, the Scythian warriors didn’t have plumbing, let alone smartphones. This is a whole new world.

🎥 Now Watch This:

You Might Also Like