Runner, Interrupted

The sounds of the city grow faint. The air smells of pine, and the wind whispers through the branches. The Alaska Pacific University Trail is rough with rocks, and Marko Cheseto struggles for balance as he runs. Looking for even patches in the dirt, he chooses his steps carefully. Each one is a decision. Once, when he had feet, he flew through these woods. He flew through them faster than anyone ever had.

Cheseto, 30, remembers how things once felt beneath those feet: the light touch of the track, the roll of the trails, the give of the red earth he grew up running on. He remembers how far those feet carried him—from a tiny village in the Kenyan Highlands across the world to Alaska and a new life as a star runner. He remembers how they propelled him to victory. Sometimes, he forgets he doesn’t have those feet anymore.

But not today. Today he remembers. Today he’s wearing metal feet inside his running shoes, and they are no match for real feet that slide over rocks and roots like water.

Cheseto has run this trail countless times since arriving at the University of Alaska Anchorage in 2008. It was through these woods that he pushed himself and his teammates and helped forge the Seawolves into a national force. And it was here that he took that last run, the one that transformed him from the greatest runner the school had ever known into…someone else.

We stop running and Cheseto searches his memory for the map of that run. He looks into the trees.

“This way,” he says, stepping off the trail. We walk along a boggy moose track until coming to an opening in the trees.

“Tumefika,” he says. “We have arrived. This is the opening. I remember seeing a light from over there.”

We stand and look at the place.

“I knew the route,” he says, pointing up a hill. “I was going to go from campus, around this way, then go home.”

“What were you thinking when you left campus?” I ask.

He shrugs. “Nothing. Kukimbia tu.”

Just to run.

As we make our way back to the car, Cheseto is subdued. This is not his usual manner: Normally, he is quick to joke. He can talk for hours. He can make you laugh so hard your stomach hurts. These are things everyone says: Marko’s a goofball. Marko’s the best. Marko was the first Kenyan I really got to know. And this: Marko was the one who brought the team together.

And soon enough, he’s joking about having more legroom in cars than he used to (which he does). We arrive at his apartment, a yellow stucco building on a street filled with identical apartments. He ascends the stairs to the second floor in a sideways manner, walks down a dark hallway, and opens the unlocked door.

Inside, David Kiplagat, the first Kenyan to come to the University of Alaska in 2004, is making milky Kenyan tea in the kitchen (formerly a professional runner and assistant coach, at press time, Kiplagat had joined the U.S. Army). Cheseto greets him before taking a seat in the living room. He takes off each Vari-Flex XC prosthesis, then leans back and dozes off.

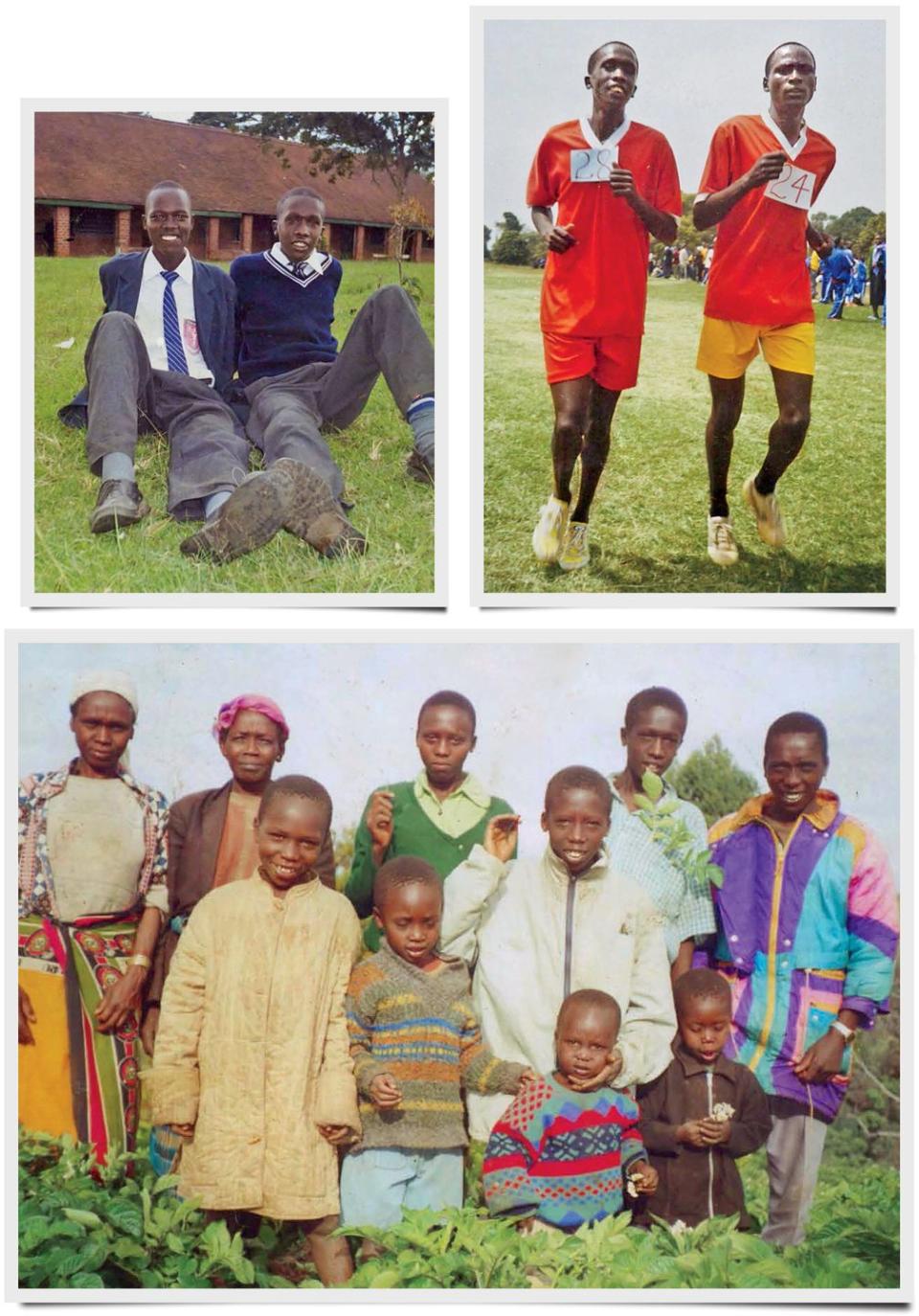

As he naps, I page through his photo album. There are images of Cheseto running races in Kenya, with friends at a Rift Valley overlook, and posing with his family of 13 (he’s the third oldest of 11) on their farm in a village called Ptop. In the background, the rolling hills are covered with small fields of crops. They farmed everything from potatoes and onions to corn, and if the crops did well, they had enough to eat.

“This place is a lot different than Kenya,” Cheseto had told me. “A lot different. Kenya is on the equator. This is the North Pole. Alaska is the end of the earth.”

Ptop, it seems, was also at the end of the earth. No buses traveled through it. Save for the sounds of chickens, cows, and goats, it was quiet. Cheseto’s father owned around 30 cows and 100 goats, and before he started school, Cheseto’s job was to look after the animals. The goats were very fast, but he was faster.

The village was far from anything. So when Cheseto started school, he would put on his blue school shorts and his white school shirt, shove his notebook into his bag, and run six miles down the dirt road to Ptop Primary School. Sometimes, he’d run home for lunch, which meant by the age of 6 he was logging up to 24 miles a day. Some years he ran barefoot. Other years, he had shoes. Sometimes he raced kids from other villages through the fields. He often won, but it was just a game. Running, for Cheseto, was never something you did apart from the rest of your life. Running was life. If you wanted to get anywhere in this world, you ran.

In 1999, in eighth grade, he represented his school at a district competition against 25 other schools. He finished fourth. It was his first hint that running might be more than just a mode of travel.

It was a time when thousands of other Kenyans were having the same realization. Worldwide, there was an explosion in the number of races offering prize money. With it came the allure of un-imagined riches. Kenya’s Commissioner for Sports and 800-meter Olympic bronze medalist Michael Boit openly encouraged his countrymen to seek profit from their talents, and soon foreign coaches and agents began flooding the country searching for the best of the best. Young Kenyan runners flocked to the training hubs of Iten and Eldoret, and in highland towns, hundreds fought on makeshift tracks for a place at the front, all hoping to be noticed by a running camp or a coach and secure a manager or a scholarship at a foreign university. The competition was brutal; they were all, in a sense, running for their lives.

Over the years, Kenyan authorities have voiced concern about foreigners exploiting the country’s surplus of talent and desire. But for most athletes, trading family, friends, and home for the dream of a better life is an exchange they’re willing to make. Hardship is something most Kenyans know well—a few years of intense pressure and long hours on an American campus can seem a fair price to pay for the opportunities it may create. Indeed, Michael Boit himself moved to New Mexico in 1973 as a student-athlete, went on to get his doctorate, and then returned home in 1987 to help change the face of the running world.

As Kenyans began to dominate distance running in the 1990s, Cheseto occasionally heard the name of his aunt, Tegla Loroupe, on the radio. She won marathons from New York City to Rotterdam and Berlin, setting world records in both the marathon and half marathon. With her first marathon win—New York in 1994—she took home $35,000.

Cheseto kept running through high school, where he grew tall and his stride grew long. Every year, he ran in the district competition, and every year, he finished third. He traveled with his school team to races, and for the first time he saw the bright lights of Nairobi, the shores of Lake Victoria, the vast blue of the Indian Ocean. With each trip, Cheseto’s horizon stretched a little farther from the hilltops of Ptop. Traveling around Kenya—and getting free bread and milk!—made him realize what being a runner could mean.

After high school, he attended teachers college in Egoji, thinking he’d eventually get a job in Ptop near his daughter, whose mother was a high school girlfriend. Over his two years at Egoji, Cheseto became a force on the track. His long, relaxed stride belied an aggressive, front-running racing style and a devastating finishing kick. In 2006, Cheseto traveled to Kigari, a small town east of Mount Kenya, for the Kenyan Teachers College Sports Association Athletics Championships, the last of his events as a student. The races were run on a simple grass track marked out in a field, ringed by spectators and set against the dramatic backdrop of Mount Kenya’s lonely silhouette.

One spectator stood out: a mzungu—white man. Word spread that he was a coach from America. Indeed, Jon Murray was from Texas, and it was the coach’s fourth trip to Kenya to scout running talent for Abilene Christian University. The small school in a dusty corner of tornado alley didn’t typically attract top U.S. runners, but in Kenya, Murray could meet as many as 80 serious recruits for one or two slots. Hard as it was to cull through all those lives—all that hope—it was a good problem for a coach to have. And Murray always had good luck at the KTCA Athletics Championships—the runners had both the book smarts and the speed to excel in the U.S. system.

After watching Cheseto finish second in both the 5K and 10K, Murray approached him. He handed over his business card, told Cheseto he was looking for runners to come run for his team, and suggested he look up ACU online. Cheseto nodded, Yes, yes, of course.

But on the long ride back to Ptop, he looked at the card and scratched his head. “There were a lot of things I didn’t know—Email? Online? Upload? I didn’t do anything because I didn’t know about online and web pages,” he says.

Electricity hadn’t even reached the village, let alone the world wide web. And besides, by then he had another daughter with a college girlfriend to support and he needed a job. So at the end of the summer, Cheseto started teaching for about $200 a month. On Murray’s advice, he took the TOEFL exam—Test of English as a Foreign Language—and did well. But beyond that, he wasn’t sure what to do.

That winter, an envelope arrived from America. Murray was now at Texas Tech University, and the envelope contained an application and magazine articles showing Kenyans at Texas Tech winning the Big 12 Conference Championships. As he paged through it all, Cheseto felt the smallness of his classroom. “Teaching was fun,” he says, “but I was hungry for more. So I thought, This is something I need to pursue. It’s better if my kids miss me and have something to eat than if I was there in Kenya and they had nothing.” He sent his application to Texas.

For months he heard nothing. But he was determined to see how far running could take him, and so that summer of 2007, he left for Eldoret.

Training camps dotted the city and runners were everywhere. Cheseto found a group to train with, and in the mornings they ran fartleks or repeats of 20 × 400 meters at 75 seconds or three-hour hill runs that climbed 4,000 feet through the Kerio Valley. They ran again in the afternoons and sometimes in the evening. On weekends, Cheseto did time trials with members of a student-athlete training camp that helps runners with their training and taking the SATs. He dropped his 5K down to 14:30.

Meanwhile, his paperwork circulated in America. Division I age restrictions made Cheseto, by then 23, ineligible for Texas Tech, so Murray forwarded Cheseto’s file to Division II schools. It landed on the desk of coach Michael Friess in Alaska. Interested in the Kenyan’s potential as an athlete, Friess e-mailed Cheseto (who now had regular web access) about running for the Seawolves.

Kiplagat had arrived at the University of Alaska Anchorage nearly four years earlier, in 2004. With Coach Friess’s help, he had brought his younger brother, Paul Rottich, over to run as well. Slowly, the school established a reputation as a welcoming place for Kenyan runners.

Alaska? Cheseto had never heard of it, although he had read about igloos in one of the geography books he’d used as a teacher. In any case, it was America. A once-in-a-lifetime chance. Of the thousands of runners he saw every day, he’d be one of the few who made it. He would run and study and work and send piles of money back home. He could send his kids to good schools. Maybe he’d become his family’s Tegla Laroupe.

Before he left Kenya, Cheseto met with Kiplagat, who was home briefly to visit his wife and kids. Cheseto peppered him with questions about life and running in Alaska, and the veteran runner assured him everything would be fine. A few weeks later, Cheseto said goodbye to his family and his kids and stepped off the red earth onto a bus for Nairobi, where he would board a plane for the land of the midnight sun.

When Cheseto landed in Anchorage in late August 2008, the sun was high in the sky. He arrived with Alfred Kangogo, a runner he’d met in Eldoret who’d also been accepted by UAA. The pair moved into a dorm with two other track-and-field student-athletes. They all spoke English, but it took weeks before they could understand each other’s accents.

Training started almost immediately. And almost immediately, Cheseto was the top runner. He liked to get out front fast and stay there. “One thing I noticed about Marko and the other Kenyans,” says Yon Yilma, a 2:29 marathoner and Cheseto’s former teammate, “was they can always dig deep and hang on when the race gets really tough. They never back down from a fight.”

Tough as he was, he had a lot to learn. In his first race, Cheseto thought he was supposed to keep up with the lead bicycle and took off like a rabbit. He ran so fast he wore out the cyclist, who had to be replaced, and eventually ran out of steam himself and finished second. Friess advised him to throttle back, and the next time out, he won.

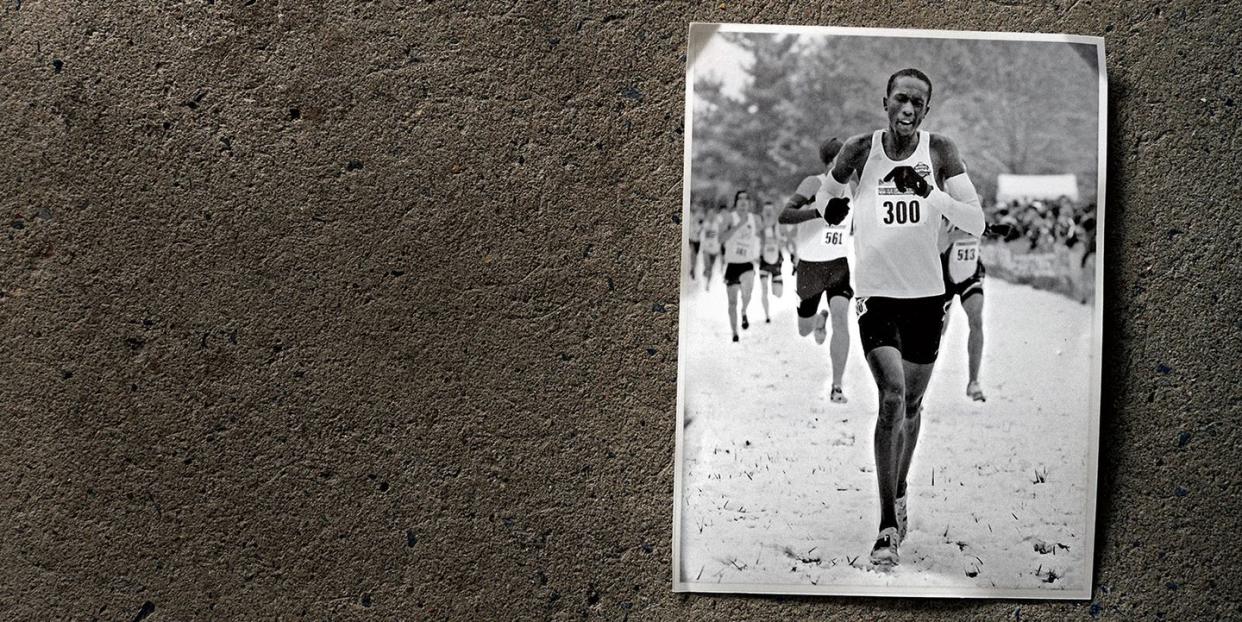

That fall, Cheseto led the cross-country team to nationals, where they finished 11th and he finished ninth—making him both All-American and the Great Northwest Athletic Conference Cross-Country Male Athlete of the Year. At outdoor track championships that spring, he was named All-American in the 5,000 and 10,000 meters, finishing fourth and seventh, respectively. He set university and conference records in the 5K, running 14:02.45, and in the 10K, running 29:08.28 at the Mt. SAC Relays.

“He was our best cross-country runner, our best 5K, 10K, and 1500 runner if he wanted to focus on it,” says Friess. “He was very assertive.”

As the year wore on and his English improved, Cheseto’s personality came out and his humor and humility won over his fellow teammates. He’d tease the women about how many cows each of them were worth in Kenya (blondes netted 100; brunettes, 10). He invited the whole team to his apartment for ugali, the stiff maize porridge of home. Thanks largely to Cheseto, the wall of politeness and self-effacement that had long separated the Kenyans and the Americans started to crumble. He became the leader pushing the team to work together, and they responded.

“He always made me feel like such an awesome person,” says Ivy O’Guinn, who was a freshman on the team during Cheseto’s third year. “Like I was the best kid on the team and a great athlete. I loved running with him.”

“He said something early on,” says assistant coach T. J. Garlatz. “He said, ‘No matter the size of a tree, it can never be called a forest.’ Basically, one runner can’t make a program, and it was time for us to come together for the sake of the team.”

In Cheseto’s second year, he moved off-campus with four other Kenyan runners. They shared a car and gave each other rides. They all put in long hours studying, working, running. Cheseto worked at the library, coming home anywhere between 10 p.m. and midnight. Whoever got home first would chop onions and cabbage and meat to serve with a giant pot of ugali. As the apartment filled with the smells of home, it filled with its languages, too: Kalenjin, Pokot, Swahili, English. The runners toggled between Kenyan news on their phones and American television.

Their apartment became a kind of decompression chamber from the strange, high-stakes world they lived in. Everything in America was different: the food wrapped in plastic, the small class sizes, the way everything—including relaxation—had to be scheduled. Time was regimented in a way it had never been in Kenya—10 a.m. meant 10 a.m., not “sometime before early afternoon.” Americans were so busy, so involved with their own lives—they lived alone, ate their meals alone. Even the noise of the city was odd: Cheseto would sometimes wake up at night hearing people talking and motors running, and wonder what was going on. The apartment became a place where they could feel a little closer to home, where the struggle to adapt felt a little easier because it was shared.

But the hardest thing was the sun—its near constant presence followed by its near total absence. In summer, Cheseto had to cover his windows to sleep, and in winter, his Vitamin D levels dropped so low he started using a SAD (seasonal affective disorder) light box whenever he could find the time, which wasn’t often. The Kenyans spent more time indoors than they ever had in their lives.

“It reaches a point in Alaska where you remember home, and then you’re like, ‘Why am I here?’” says Micah Chelimo, an engineering student and 10-time All-American who came to Anchorage a year after Cheseto. “We start missing our parents, our place, and those kinds of things. It makes you feel…not the same.”

All the Kenyan runners experienced the “acculturative stress” (the preferred term to “culture shock”) that comes from immersion into a new world. Such stress can manifest as depression, anxiety, and psychosomatic problems like sleeplessness and ticks. It can take years—up to 12—before a person can reconcile where he is with where he came from and integrate his new identity into his old one.

“We know there’s some culture shock,” says Friess. “But ironically, there’s not much. It gets frustrating sometimes when people say, well, ‘Why are these Alaskans recruiting Kenyans?’ They don’t understand that Anchorage has one of the most diverse populations in the United States. I think it smacks a bit of racism when people suggest that a Kenyan somehow isn’t able to come in and adapt to an environment like this.”

Whatever acculturative stress they may have felt, all the Kenyans in Alaska had worries—they worried about home and school and the future, but they rarely talked about them. You just didn’t do that as a Kenyan—life was hard, and you either laughed it off or toughed it out. Whatever issues you had, you dealt with them yourself.

Cheseto certainly didn’t escape the stress, but for a while, he did exceedingly well. By his sophomore year, he was at the top of his nursing classes and dominating his races. That fall, he won nearly all of his cross-country races, and the Seawolves once again made it to nationals, finishing 17th. In the spring, Cheseto set a conference record of 13:58.85 in the 5,000, and finished sixth at nationals in both the 5,000 and 10,000 meters and was again named All-American. And he had successfully lobbied Coach Friess to recruit his younger cousin, William Ritekwiang, a promising student and runner from Kenya.

Ritekwiang was as shy as Cheseto was gregarious. But he was quick to laugh, and he loved to dance and would show off his moves in the weight room. The cousins became constant companions—eating, training, studying, and watching movies together. That spring, the pair ran the Twilight 12K road race in Anchorage—Cheseto set the course record of 37:07, and Ritekwiang finished a strong second. By the fall of Cheseto’s junior year, his cousin’s speed was sharpening and there were days when Cheseto struggled to keep up. Everything seemed fine, better than fine.

But as his third winter approached, and the snow started to fall, and the North Pole tilted away from the sun, Cheseto started feeling down. He couldn’t figure out why. Maybe it was the surgery he’d had to fix a lazy eye. Maybe it was just “normal stuff,” as he puts it, the pressures of home, of school, of life. Maybe the stress of acculturation was catching up to him. Maybe it was the darkness. Maybe it was all of these things.

He lay awake at night, unable to sleep, not knowing why he felt bad, what to do, or how to fix it. At practice, he was no longer the gregarious goofball, and his teammates worried. Coach Friess intervened and got Cheseto into counseling, from which he also got sleeping pills. Both seemed to help.

Before long, Ritekwiang, too, started acting strange.

He began approaching the other Kenyans, asking their forgiveness. They had no idea what he was talking about.

“He was saying, ‘If I have done something wrong to you, please forgive me,’” Kiplagat recalls. “And I was like, ‘Why do I need to forgive you? What have you done to me?’”

It was odd, but none of the Kenyans thought much about it. They were just all so busy. When Ritekwiang called Cheseto one cold day in February and said he had something to tell him, Cheseto told him they could talk later.

That night, Kangogo arrived home to the apartment and found the door—which they always left open—locked. He called Cheseto, Kiplagat, and Chelimo—none of them had keys, either. Ritekwiang didn’t answer his phone. The foursome stayed the night at another Kenyan teammate’s place.

When they returned the next morning, the door was still locked. Not knowing what else to do, they called the police, then Friess. Officers pried open a window, and Chelimo, the smallest of the group, climbed through and unlocked the door. The police told the friends to wait in the front entry while they cleared the rooms.

As they moved through the apartment, one of the officers saw a light coming from under the bathroom door. He pushed it open. Ritekwiang was hanging from the showerhead by an internet cable. His body was stiff.

Police did not immediately tell the friends what they’d found, but everyone knew it was Ritekwiang—he was the only one missing. Cheseto didn’t say anything. His mind spun. It didn’t make any sense. William? Why? Just the day before, they’d run together, had a great workout. His cousin had gone to all his classes—his bag was full of assignments to turn in. None of them knew what to say or think. Everyone was blindsided.

“There was zero warning,” says Friess. “Zero. We pay so much attention to these kids, how they’re feeling, how they’re doing academically. You’re with these athletes all the time, monitoring them all the time. That was the farthest thing from my mind.”

“I remember our last long run,” says Cheseto. “He was getting very fast. We ran along the Coastal Trail toward the airport, and I was struggling to keep up with him. He was so focused. That year, he was going to go to nationals. And we were going to Las Vegas for our spring break. He was so excited about going there, and enjoying the sun.

“It was such a happy life when he got here,” Cheseto continues. “Then he was gone. There was not one week of asking, ‘What might be going on with William?’ Not even a day. It was so abrupt.”

There were few clues into Ritekwiang’s state of mind. Police found an outgoing text on his phone from two days earlier that read, “Hey, pray for me bro, pray for me coz I am so down.” When Cheseto went to Ritekwiang’s Facebook page, he was shocked. Ritekwiang had deleted every photo. Erased every memory.

The only image left was Ritekwiang’s profile photo—a picture of the rolling hills and blue sky of home.

Ritekwiang’s body was sent back to Kenya. The runners tried to resume their routine, but a hole had been ripped in their team and their lives. They had lost Ritekwiang, and soon they would lose Cheseto, too.

Every day, all day, Cheseto ran a tape of questions over and over in his head. Was there something he’d missed? Had he pushed his cousin too hard? Should he have met him that day, instead of telling him he was too busy? Should he have brought him to Alaska in the first place?

The weight of questions without answers bore down on him. He couldn’t shake the feeling that Ritekwiang’s death was his fault, and he couldn’t find a way out of his terrible maze of thinking. There was no more bride-pricing. No more jokes. No more ugali dinners. “He was there,” remembers teammate Susan Bick, “but he wasn’t really there. He hardly talked to anyone.”

“After William died, everything changed,” says Chelimo. “Marko didn’t have the energy to study. He tried to read, but couldn’t. He had some classes that he didn’t finish, so he was afraid he wouldn’t finish school. And he was so close.”

To give him time to recover, Friess red-shirted Cheseto for the spring track season. Then in April, Cheseto took too many sleeping pills, and the university sent him to a supervised psychiatric unit at the local hospital. (Cheseto doesn’t recall wanting to commit suicide. He says he simply wanted to “feel better.”) There, he says, he was put on a “very high dose” of an antidepressant, along with an anti-psychotic. He didn’t run at all, and by the time he was released a month later, he’d gained 20 pounds.

Over the summer, he seemed to be doing better. By the time school started, he was back living with Kangogo, Chelimo, and Kiplagat (who were now in a new apartment). With one season of track eligibility left, he started training that fall for the spring meets. But he was out of shape—the former star was now the slowest runner on the team. Everyone could see he was struggling, so they tried to keep him involved beyond their workouts together. He became a team manager, traveling and supporting the runners he’d once led. As the semester wore on, he seemed to laugh and joke a little more, and his friends thought he was continuing to improve.

But then one Sunday in early November, he woke up in a dark mood. Throughout the day, he tried to talk to his friends about how bad he felt, but they were in a hurry. They had too much to do. They would talk later.

That evening, Cheseto went to school to drop off the car keys for Kangogo at the athletic center. He grabbed some antidepressants from his locker—he doesn’t remember how much he took. Then he went to the library to study, but didn’t feel like it. Instead, he felt like running. So at around 7 that Sunday evening, he headed out on the Alaska Pacific University Trail near the school. He wore two jackets, no hat, no gloves.

Falling snow muffled his footsteps. In the quiet that surrounded him, everything seemed very far away. At some point, he took a right off the trail and ran into the woods. That’s all he remembers.

He doesn’t recall taking painkillers the day he went missing, as later media reports claimed. Again, he says he wasn’t trying to kill himself. “All I remember,” he says, “is that I wanted to go running.”

Depression impedes memory, so it is possible Cheseto was trying to end his life. It’s also possible his medications played a role in his decisions that day: Certain antidepressants have been linked to increased thoughts of suicide, and an overdose can cause agitation, restlessness, unusual drowsiness, and sudden loss of consciousness, according to the Mayo Clinic—all of which Cheseto experienced. What he does remember is that he was under a lot of pressure, in some kind of fog, and feeling real pain. And the two things that helped him put his trouble behind him were pills and running.

As Cheseto lay in the snow that Sunday night, six inches of snow fell. The temperature dropped into the low 20s. When Monday morning broke, he remained still, his eyes closed, his mind somewhere else.

At 3 p.m. on Monday, a massive search was organized with the Alaska Mountain Rescue Group, the state troopers, local police, and Alaska Search and Rescue Dogs. They combed the trails. They flew helicopters over the woods. The dogs searched for a scent. They found nothing.

After practice that afternoon, Friess gave his team the news: Marko is missing.

Some of the runners wept. Some of them assumed it was Ritekwiang all over again. Most of them went back outside and ran along the trails that Cheseto knew. They called his name. They looked for footprints or lumps in the snow. They ran late into the night. And they, too, found nothing.

“I had a speech I was supposed to give the next day with Marko,” says Cheseto’s former teammate Yon Yilma. “I had to give it myself, but in the middle of it, I said, ‘I can’t do this.’ I walked out of the class in tears.”

The search continued through Tuesday, and by practice that afternoon, Cheseto’s teammates had begun to lose hope. Once again, no one knew what to say, or what to think. On Wednesday morning, dive teams were to be dispatched to search local lakes. This time, they would be looking for a body.

It was snowing when Cheseto opened his eyes. At first, he had no idea where he was. He assumed just a few hours had passed, but it had been days. It was around 2 a.m. on Wednesday morning, about 55 hours after he’d left for his run on Sunday evening. The temperature was 10 degrees. He was so cold.

Cheseto tried to lift his head, but it just moved limply from side to side. For a while, he lay in the snow beneath a tree, unable to move, getting colder and colder. His thoughts veered from his teammates, to his cousin, to his daughters, to Ptop. All the things in life he still had to do. He had to get out of the woods.

When he finally managed to sit up, he looked down at his feet. Covered in snow, they felt heavy as anchors. He grabbed the trunk of the pine tree and pulled himself up. Once standing, he walked in place until he began to feel his legs. He could not feel his feet.

Cheseto walked slowly through foot-deep snow toward the lights of a power station on a small hill. He eventually reached the trail he’d left days earlier, and followed it through the woods for nearly a mile until he came to a steep hill. He remembers this hill. He remembers it because of how he felt staring up at it—“I was so dead,” he would later say. On the way up, he stopped several times to rest. If there were another hill like it, he is certain he wouldn’t have made it. But at the top, he saw the lights of the city, of his school, and heard the sound of cars, and he felt “a kind of courage.” As he descended, he thought he saw a river before him. How could he cross a river? But his frozen mind was playing tricks on him. He summoned the strength that had once made him one of the fastest runners in Alaska, and one blocky step at a time, continued toward the lights.

He pushed himself through the front door of the Marriott Hotel. The air was warm. It was quiet. Flames were flickering in the fireplace. Cheseto collapsed on the lobby floor.

The night manager rushed over and helped him into a chair by the fireplace, and put a blanket on him. Cheseto was shaking violently. His hands were swollen to twice their normal size and his skin resembled thick plastic. His feet were hard as chunks of wood, and frozen to his running shoes.

Dehydrated and hypothermic, Cheseto was disoriented. He still didn’t know what day it was, and when he learned it was Wednesday, he was shocked at how much time had passed. Once at the hospital, doctors immediately rehydrated him, and began thawing his hands and feet in warm water, causing searing pain as the nerves awakened.

By 4 a.m. that Wednesday, phones were ringing across Anchorage as the word spread: Marko is alive. Friess, Garlatz, and Cheseto’s closest friends rushed to the hospital, overjoyed.

Days passed. Doctors used a gamma camera to look through Cheseto’s hands and feet and monitor the bloodflow. The skin on his hands was soft and puffy and covered in massive blisters, and when it started to slough off, it resembled a plastic bag. But his hands looked better every day.

His feet, however, looked worse every day. Gangrene began to spread. Cheseto could smell the rotting flesh. When he looked at the scans on the screen, both feet were darker than the night sky over his boyhood village.

His feet were dead. He knew this. He knew what it meant. And when doctors drew the lines on his legs where the cuts would be made, it was as if they were separating his past from his future; who he had been from who he would become.

When he woke up from the surgery, he didn’t feel any different. Were his feet still there? The nurse came in and asked if he wanted to look. He hesitated for a moment, gripped by a fear he’d never known—the fear of something that can never be undone. She lifted the sheet.

The cuts seemed higher than he had expected—about six inches below his knees. His stumps were swollen and bandaged and trailed off into nothing. Nothing to stand on. Nothing to run on.

The community of Anchorage rallied around Cheseto. The university set up a fund to offset his medical expenses and collected $17,000. Other double amputees visited him in the hospital to show him how life goes on without feet. Someone mailed him a copy of Oscar Pistorius’s autobiography. Others told him stories of successful amputee athletes.

Gradually, he learned how to get out of bed and how to get in and out of his wheelchair. Within weeks of his operation, he was walking unassisted on his prostheses. He learned to climb stairs. He worked out in the pool and spun on the exercise bike. His teammates—once anticipating their friend’s final triumphant season—now stood by him, awkwardly trying to support his efforts to adjust to this new life.

His hands hurt all the time, especially when a cool breeze blew. But worse was the pain he felt in the space where his feet used to be. Every day, it came in waves that washed over him and left him exhausted. Sometimes it felt like a knife was stabbing his invisible toe; sometimes it was a deep itch from inside his missing heel. “Almost every day, I have pain,” he says. “Every day. That’s when you remember you don’t have feet. But I know complaining about it will not help, or to think, Oh, it would be better if I had feet. Fortunately, that is a path I have been able to avoid.”

As a runner, he had managed the pounding pain of the final lap by focusing his mind. He did the same now, focusing hard on the fact that his feet were gone. Sometimes, it worked.

As the New Year began, he relearned how to do the simple things, and tried not to let his worries swallow him—worries about his visa status, what would happen if he were sent home, his pile of debt. He owed $30,000 in medical bills. His future was full of unanswered questions. So he focused on what he could control—what he could do. Without telling his doctors, he quit his antidepressants. In February, he appeared in a local TV special about depression. That spring of 2012, he served as a guest starter for a local race. And he ran. Using his walking prostheses, he couldn’t go far or fast, but at least he could go. Gradually, he started feeling better—more like himself. As he focused on what he could do, his darkness began to lift. With his teammates, he began joking more.

“We told him we need the Marko we used to know,” says Chelimo. “And he responded well. Now he’s like super-Marko. He jokes about everything.”

In June, he lined up for the 6K leg of the Twilight 12K & 6K. He was no longer Marko Cheseto, course record holder and Kenyan phenom. Now, he was Marko Cheseto, Paralympic class T43—double amputee below the knee. At the start, he took off as fast as he could on his metal feet. Sometimes he walked. Sometimes he jogged. He finished the 6K in 43:53, more than double his record-setting pace from two years before, when he’d run the event with William. He knew he could go faster.

That summer, he sat in his apartment watching the London Olympics and Oscar Pistorius—the South African was the first amputee to reach the peak of world competition. Cheseto got texts and calls from around the world telling him he could do that, too—he could become the next great blade runner.

The story of Cheseto’s struggle to run again eventually reached Brooke Raasch, husband of celebrity amputee triathlete and Ironman Sarah Reinertsen. Raasch works at Ossur, a prosthesis company that made Reinertsen’s blades, and he contacted Cheseto about testing a new product—the Vari-Flex XCs, a small, C-shaped curve with enough flex to serve as a hybrid walking/jogging foot. Raasch encouraged Cheseto to also apply for a grant from the Challenged Athletes Foundation. If approved, Cheseto would receive a pair of Flex-Run blades—prostheses designed specifically for distance running. Cheseto readily agreed to be a tester, and sent in his application for the blades.

The hybrid XCs arrived before Christmas of 2012. After a fitting with his prosthetist, Cheseto hopped around the room, ecstatic. It felt like he was on a trampoline. “When I got those, I thought they were so springy,” he says. “They were wonderful!”

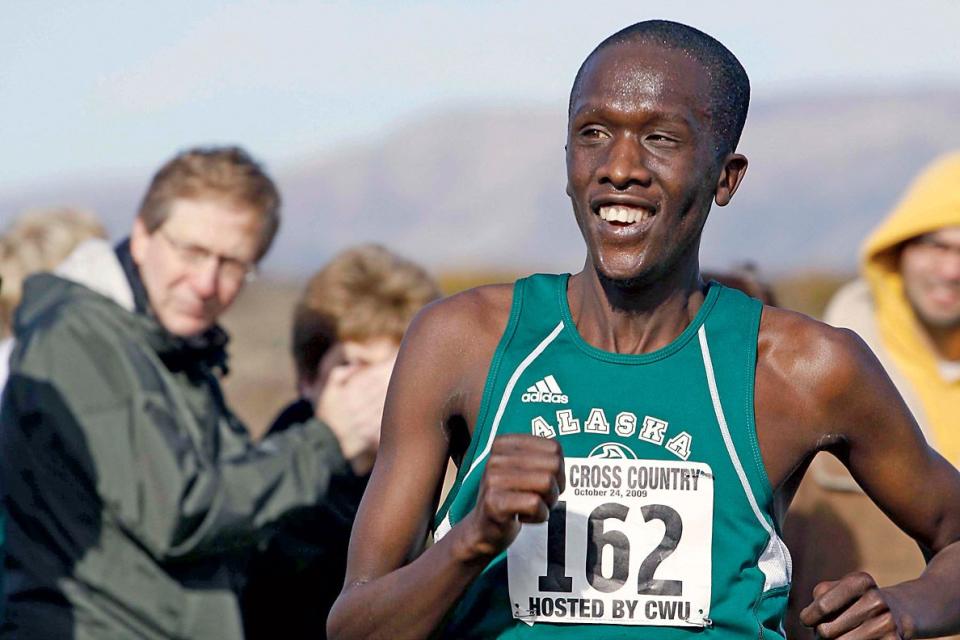

He started training immediately, building up to hour-long runs on the university’s indoor track. Eventually, he was logging up to 40 miles a week. In March 2013, he entered a local 5K and finished in 26:58—averaging three minutes per mile faster than he ran the previous year at the Twilight 6K. He signed up for the 6K again, certain that he could better his time.

One week before race day, the distance-running blades arrived.

Cheseto is sitting on the metal bleachers at an outdoor track near campus. It’s late May, and the afternoon sun is high above us. The Chugach Mountains cut a jagged line across the sky. In his hands, Cheseto holds one of the blades. It is a thing of beauty, an elegant arc of carbon fiber.

He’s had the Flex-Run blades just a few days—this will be his first real workout on them. He takes out his Allen wrench, unscrews his Vari-Flex XCs from the sockets that fit over his stumps, and attaches his new running feet. Then he stands.

The prostheses make him three inches taller and push his upper body forward. He struggles at first to keep his balance. He lifts up one then the other, slowly running in place. Then he lopes out onto the track.

The transformation is stark. When he runs in the XCs, his weight is oddly centered. His knees seem to search for the right direction of travel, and his legs never fully straighten. He is not graceful. But as he runs on the blades, there is a metamorphosis: His stride becomes fluid, light, as if the memories are flowing back into his body. There is an effortlessness and a familiarity to how he runs, as if he’s floating.

He circles the track and sits down, and we’re soon joined by T.J. Garlatz, Cheseto’s former coach, and another assistant coach, Anthony Tomsich, who are at the track running their own workout. (Tomsich used to run for Western Washington University against Cheseto. “Sort of,” says Tomsich. “I was way behind him.”) They admire the blades for a minute until Garlatz asks, “Think you can do a few strides?”

Cheseto smiles. “I can set the pace.”

The trio jogs halfway around the track before Cheseto surges and the coaches, caught off guard, work to catch up. They follow the strides with a timed quarter-mile, clocking in at 75 seconds. After a few easy laps and a brief rest, Garlatz and Cheseto walk to the far end of the track for a friendly 100-meter dash.

The runners bolt off the line. At first, it’s hard to tell who’s ahead, but then it’s clear—Cheseto is leading. He holds the coach off, then overshoots the finish and runs far into the grass because he doesn’t know how to stop yet.

Garlatz returns to the bleachers, stunned. “He’s going to be fricking awesome again,” he tells me. He turns around and yells, “Hey, Marko! Maybe we can get you down to 14-flat again!”

After they leave, Cheseto and I sit on the bleachers. He rolls down his silicone liner and pours a pool of sweat down onto the concrete.

“So,” I say. “Looks like you’re going to be a runner again.”

“Looks like it,” he says.

“How does that feel?”

“That’s a very good feeling.”

Twilight doesn’t really come to the Twilight 12K and Skinny Mini 6K. The summer sun hangs in the sky until the small hours of the night. The race starts at 7 p.m., but it might as well be noon.

We arrive early. About a block from the starting line, on a strip of parkway that runs through downtown Anchorage, Cheseto finds a bench and sits down to change into his blades. I had asked him earlier if he was nervous. He’d said no: “Running is the easiest thing in the world. You just put one foot in front of the other and make sure you are going forward.”

Back On Track “I still have to do things in my life, and one of those things is being a professional runner. I need to compete again.” / Photo by Joe Pugliese

The local news media spot him quickly. They crowd around, peppering him with questions, which he answers patiently as he locks his blades in. As the cameras are rolling and reporters are in the middle of their questions, Kangogo and Ruth Keino (who arrived in Alaska a few days before Cheseto) jog past on their warmup. Cheseto jumps up and runs after them. “I’m coming!” he yells.

The three runners circle the block together, laughing and chatting. When Cheseto returns to the bench, he’s smiling in a way I haven’t seen before. Certainly, there is still much on his mind. His future is uncertain. As a grad student studying engineering and science management (he completed his nutrition degree in 2012, after switching out of nursing), he’s allowed to stay in the U.S. as long as he’s a student. After school, if he doesn’t land a job, he’ll likely have to return to Kenya. He’s still under a mountain of debt that he’s determined to pay off—somehow. And he hasn’t seen his family in more than five years. But one thing is certain—he is a runner again. In fact, he was never anything else.

“When people face challenges in life,” he says, “they spend so much time going back to, ‘How did it happen?’ and ‘Why did it happen?’ They spend so much time trying to judge themselves on what happened instead of forging ahead, instead of thinking of ways of going through it and making life better. I still have to do things in my life and one of those is being a professional runner. Having had over 10 years of competing, I have that in me now. I need to compete again.”

With just a few minutes left before the start of the 6K, Cheseto hurries over to the starting line beneath a giant inflatable arch. Several runners motion for Cheseto to move to the front. He walks over, leans forward.

A loud tone sounds and Cheseto sprints into the lead. For several blocks he stays there, until the road veers down a steep hill and he loses ground, not yet confident on his blades. The route crosses a small wooden bridge, which bounces and throws him off balance again. More people pass him.

He’s following a bike path along the ocean to the halfway point when a sharp pain shoots through his right leg—his socket is misaligned by a fraction of an inch. It gets steadily worse, but he focuses on the race and blocks out the pain.

Limping, he digs in for the final uphill kilometer and sprints through the chute. He finishes 28th out of 916 with a time of 26:19. He has knocked nearly 18 minutes off last year’s time, and another 4:43 off his 6K pace.

Cheseto is again mobbed by media hungry for comments, for insight, for inspiration. He’s tired, but he stands and answers their questions as best he can. Slowly, the reporters trickle away. He spots his teammates and limps over to them. Almost immediately the group is laughing as Cheseto goes over the highs and lows of the race, joking that he has another race record—for amputees!

He stands for a while with his friends. Beneath him, the blades bend slightly under his weight, the weight of so many things. After a few minutes, with the sun shining bright in the evening sky, Cheseto walks off across the grass with a smile on his face, having reached the end of one long road and the beginning of another.

Story Update · March 3, 2016 From writer Frank Bures: After this story ran, Marko Cheseto focused on qualifying for the 2016 Paralympic Games in the 200- and 400-meter events (the latter is currently the longest event available for double amputees). At the Drake Relays in Des Moines, Iowa, last April, he competed against double amputees, single amputees, and a blind athlete in the 200 meters, and while he finished last, he ran a PR of 24.36. Last October, he was scheduled to travel to Qatar with the Kenyan Paralympic team to run the qualifying rounds for the 2016 Paralympics in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, but the Kenyan government pulled the team’s funding at the last minute, and the trip was cancelled. Cheseto has since set up a GoFundMe page in an effort to secure training and travel funds for Rio. For now, he's training around his full-time job as sports coordinator for the Boys and Girls Club of Alaska—and his growing family. In 2014, Cheseto married an Alaskan woman who also attended the University of Alaska; the couple now has a 10-month-old daughter. That same year, Cheseto’s younger brother Henry joined the University of Alaska cross country team. As a freshman, Henry led the team to five first-place finishes and, in 2015, finished third at NCAA Division II Nationals. Cheseto is also working on a book about his life with writer Andy Hall, author of Denali's Howl: The Deadliest Climbing Disaster on America's Wildest Peak.

You Might Also Like