The Royal Bride Who Wore Pink

Remembering The Royal Bride Who Wore Pink

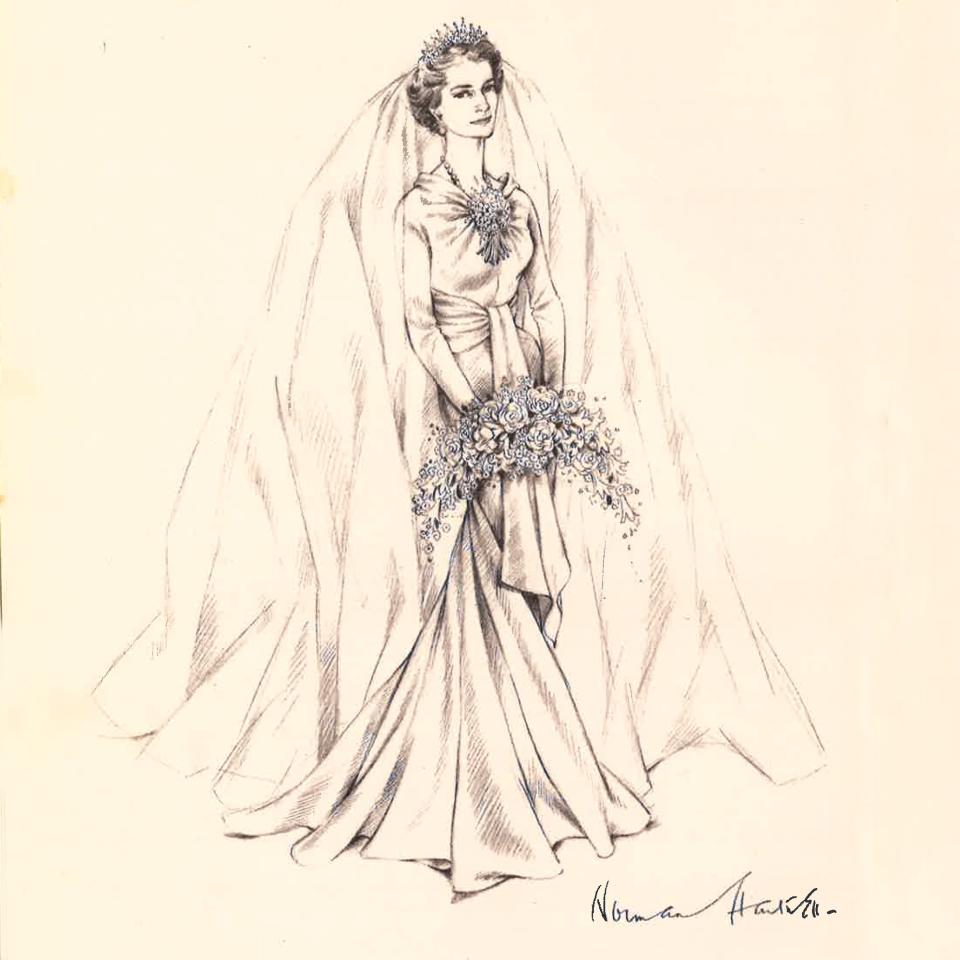

Norman Hartnell’s sketch of Princess Alice, Duchess of Gloucester’s a blush-hued wedding gown, 1935. From Silver and Gold by Norman Hartnell, 1955.

Photo: Courtesy of Evans Brothers Limited

Princess Alice, Duchess of Gloucester, wearing her custom Norman Hartnell gown, on her wedding day, November 6th, 1935.

Photo: Getty Images

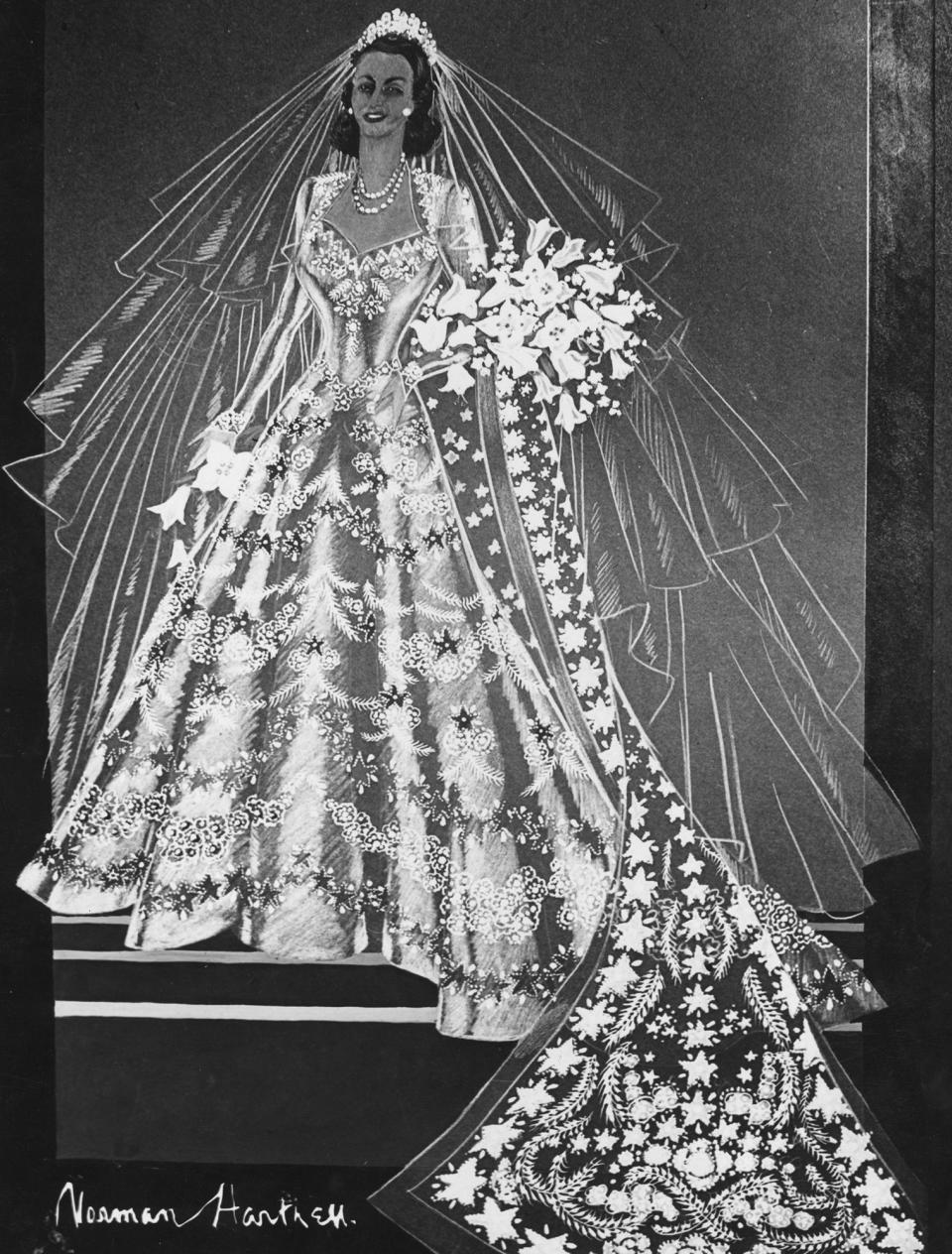

Norman Hartnell’s sketch of Princess Elizabeth’s wedding gown, 1947.

Photo: Getty Images

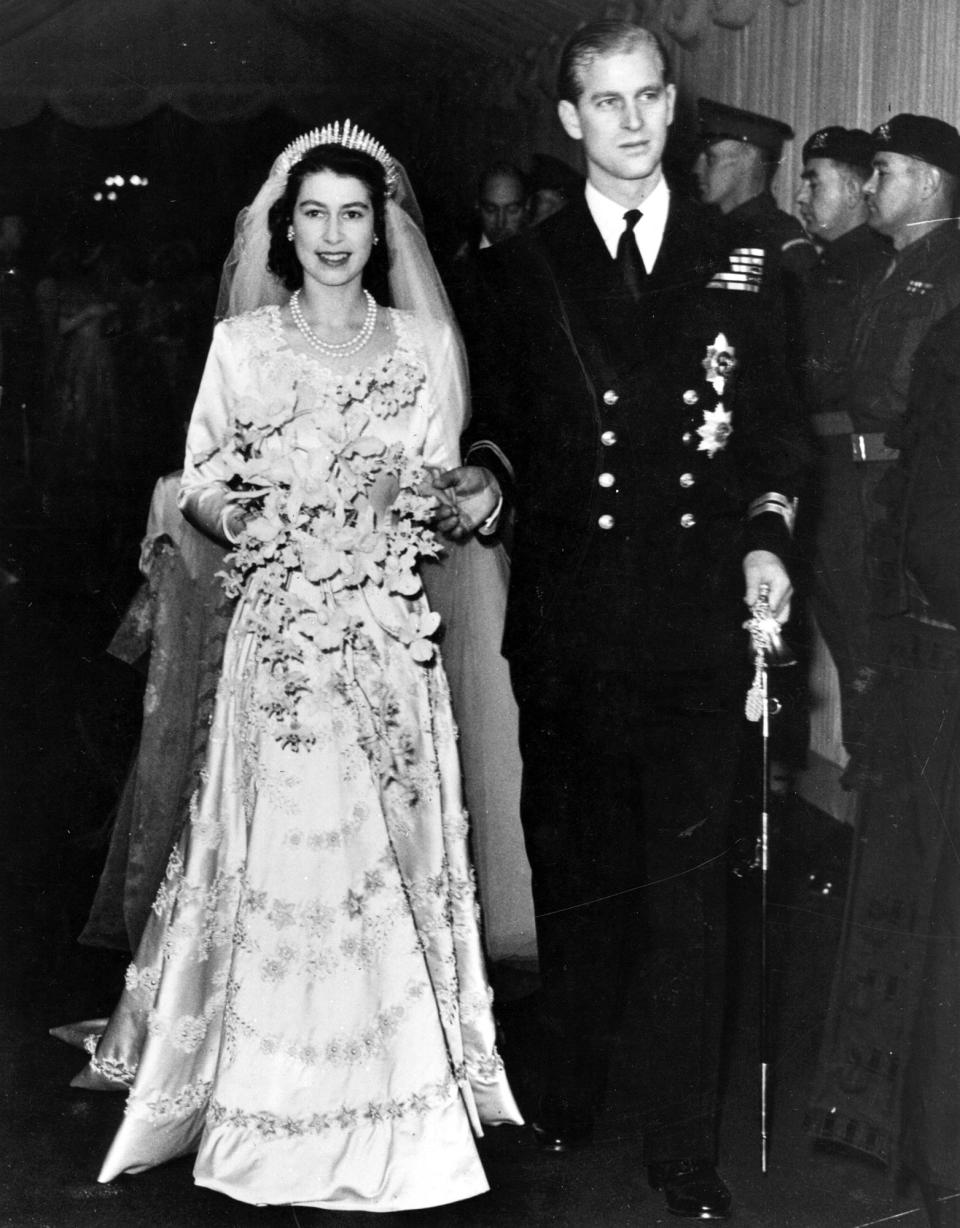

Princess Elizabeth in her custom Norman Hartnell gown on her wedding day, November 20th, 1947.

Photo: Getty Images

Norman Hartnell’s sketch of Princess Margaret’s wedding gown, 1960

Photo: Getty Images

Princess Margaret in her custom Norman Hartnell gown on her wedding day, May 6th, 1960.

Photo: Getty Images

Margaret Campbell, Duchess of Argyll’s custom Norman Hartnell wedding gown, worn on February 21st, 1933.

Photo: V&A Images / Alamy Stock PhotoWhen the elfin beauty Lady Alice Christabel Montagu Douglas Scott wrote to the London couturier Norman Hartnell from Drumlanrig Castle in 1935 asking him to design the dress for her November wedding, it set the designer on a career trajectory that would define him as one of Britain’s great royal image-makers of the 20th century.

Lady Alice was the daughter of the 7th Duke of Buccleugh, the largest landowner in Scotland, and was engaged to be married to the soldier Prince Henry, the Duke of Gloucester, son of King George V and the formidable Queen Mary, and younger brother of the future King George VI (and the Duke of Windsor). Most importantly for Hartnell, the Duke’s nieces Princess Elizabeth (the future Queen Elizabeth II) and her sister Princess Margaret Rose were to be bridesmaids.

To the horror of his parents, the Duke had had an affair with the dashing aviatrix Beryl Markham. It was thought advisable to marry him off to an appropriate consort as soon as possible. And pretty Lady Scott was certainly to the manor born, having been brought up between a series of treasure houses of such magnificence—along with Drumlanrig there were Boughton, Bowhill, Dalkeith, and Eildon Hall—that her future London residence, York House at St. James’s Palace, must have seemed humble in comparison (Prince Charles would subsequently make it his home). As for the Royal Pavilion at Aldershot, the couple’s first marital home, conveniently near the Duke’s regiment, his wife noted that “the only royal thing about it was my husband’s presence.”

The Duke was the first royal prince to have been educated at school (even his older brothers had tutors instead). He was, however, no intellectual, and like his brother the future King George V, suffered from speech impediments. His proposal to Lady Scott, the sister of one of his great friends, was singularly lacking in romance—he “mumbled it as we were on a walk one day,” she later recalled.

In his giddy 1955 autobiography Silver and Gold, Hartnell noted Lady Alice’s “beautifully moulded cheek bones and the smile which someone has described as ‘like that of a forest gnome’” when she came to his chic Bruton Street salon in a stately 18th century townhouse.

The salon had recently been decorated by the fashionable Norris Wakefield in faceted mirror paneling and painted a eucalyptus green-grey that Hartnell felt was the best neutral foil to his prefered rainbow palette of colors (Wakefield’s interior is preserved as one of London’s listed monuments of historic importance). The gnomic creature selected some ensembles from Hartnell’s collection for her trousseau (including a velvet going-away outfit), and they discussed the wedding dress. “Strict simplicity” was the bride’s command, which must have chilled Hartnell’s marrow, as he loved over-the-top theatrical effects and the “jolly twinkle of sequins.” His dress for the fashionable debutante beauty Margaret Whigham (now in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum) for her marriage to Charles Sweeney two years earlier is a case in point: With its wide hanging medieval sleeves and elaborate star embroidery edged in pearls, it took thirty seamstresses six weeks to make, but the bride was still appalled when Hartnell submitted a bill for 54 pounds.

Hartnell did, however, approve of Lady Scott’s insistence on a tulle veil, feeling that “a drifting cloud of crisp modern tulle is much more becoming” than dowdy heirloom lace that might hang “lank and discoloured with age” like “some attenuated judge’s wig.”

Hartnell did as he was told and produced a dress of modest simplicity, with long, narrow sleeves and a high neckline draped into a nosegay of artificial orange-blossom. The cathedral train was appropriate to the intended setting: Westminster Abbey. “Because of the dim lighting in the Abbey it was considered that the dress should not be in stark white, but in a soft tone with something of the glimmer of pearl,” noted Hartnell in his autobiography, discreetly overlooking the fact that the bride, at 34, (then considered relatively old to wed) perhaps also wanted a less maidenly tone.

Hartnell’s dresses for the adult bridesmaids were similarly austere, featuring wider sleeves and wider necklines, the latter decorated with artificial flowers. He initially conceived “sophisticated Empire-style” dresses for the young bridesmaids, but their grandfather, King George V, requested something “girlish” instead, and the original concept was replaced with short dresses of pale pink satin, trimmed with graduated tiers of ruffled tulle.

A lavish wedding was planned for Westminster Abbey, but the bride’s father died soon before the planned ceremony and the groom’s father, George V, was in fast-ailing health, so it was deemed appropriate to hold a far more modest wedding at the private chapel at Buckingham Palace. The bride wore an ermine blanket stole in the glass carriage on her way to the palace to guard against the winter chill. In deference to the circumstances of the wedding, there were no photographs during the ceremony itself, but afterwards the beaming bride and her diffident royal groom took to the famous balcony at Buckingham Palace, where she waved to the crowd with a whisking hand movement never seen before or since (British Pathe News was there to capture the moment). A stool was brought so that Princess Margaret Rose could see the crowd and the crowd could see her tulle ruffles.

In addition to the formal wedding party portraits, the bride sat for the fashionable photographer Madame Yevonde, famed for her surrealist portraits of society beauties and her innovations in Vivex color printing. In Madame Yevonde’s portrait, Hartnell’s “glimmer of pearl” satin clearly reads as blush pink and, rather astonishingly, the photographer has placed a bouquet of very dark red roses at the bride’s feet, perhaps intended to complement and set off the pink.

Hartnell’s pink symphony was well received: “We are very pleased,” said the formidable Queen Mary. “We think everything is very, very pretty.”

She soon ordered some evening gowns for herself, haggling over the price in a manner that can only be described as regal: She insisted that the 35 guineas Hartnell had asked for each of the three dresses she ordered was not enough, and made it clear that she would pay 45 each instead.

Delighted by what she had seen at Hartnell’s salon, the little princesses’ mother also became a client. Although the revered court dressmaker Madame Handley Seymour, who had made her wedding dress (copied from a model by Jeanne Lanvin), made the coronation robe, Hartnell dressed the Queen for the state visit to France soon after. When the Queen’s father died, her multicolored wardrobe had to be entirely remade in two weeks. Hartnell cleverly suggested that instead of funereal black, the dozens of ensembles should be made in tones of white, which also had a precedent for royal mourning. These clothes proved eminently photogenic, and the romantic Winterhalter and Hayter-inspired ball gowns had an impact on Paris designers including the young Christian Dior. Hartnell’s triumph led to him becoming the Queen’s official couturier for the rest of her life. (Hartnell was knighted by Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, in 1977.)

I visited the Hartnell salons in the 1980s, long after the designer had died, and saw there a mannequin of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother, who was still having her shimmering chiffon print dresses and spangled ball gowns made there by her loyal old dressmakers and tailors. Hartnell would subsequently design both the Botticelli-inspired wedding dress for Princess Elizabeth in 1947 and her magnificent coronation robe in 1953. Queen Elizabeth II’s sister Princess Margaret, meanwhile, was dressed by Hartnell for her wedding to Anthony Armstrong-Jones. Like Lady Alice, Armstrong-Jones also insisted on simplicity for his wife’s dress, and Hartnell’s austere design of white organdie set the benchmark for royal chic.

After a lifetime of royal service, Princess Alice, Duchess of Gloucester, having outlived her husband by three decades, died in 2004. She was 102.