Robert F. Kennedy Jr. Says He Would Take a Covid Vaccine

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The quarantine has been okay. The monotony is no fun, but he can’t complain, and doesn’t. Mostly Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is just at home in Brentwood, Los Angeles, with his family, working and doing some surfing with his kids once in a while. One day everyone got attacked by bees in the yard—that was scary for a few minutes.

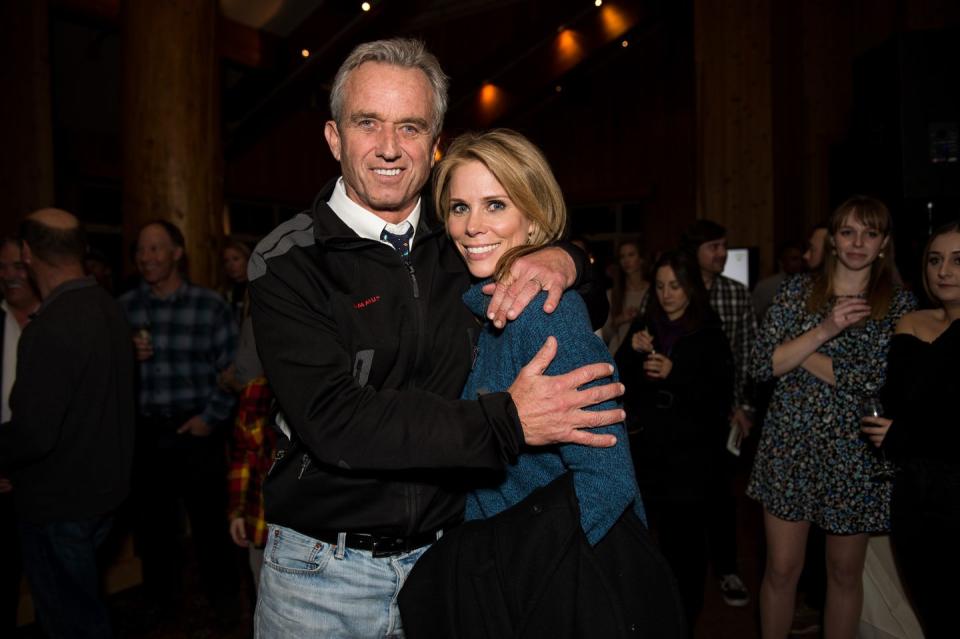

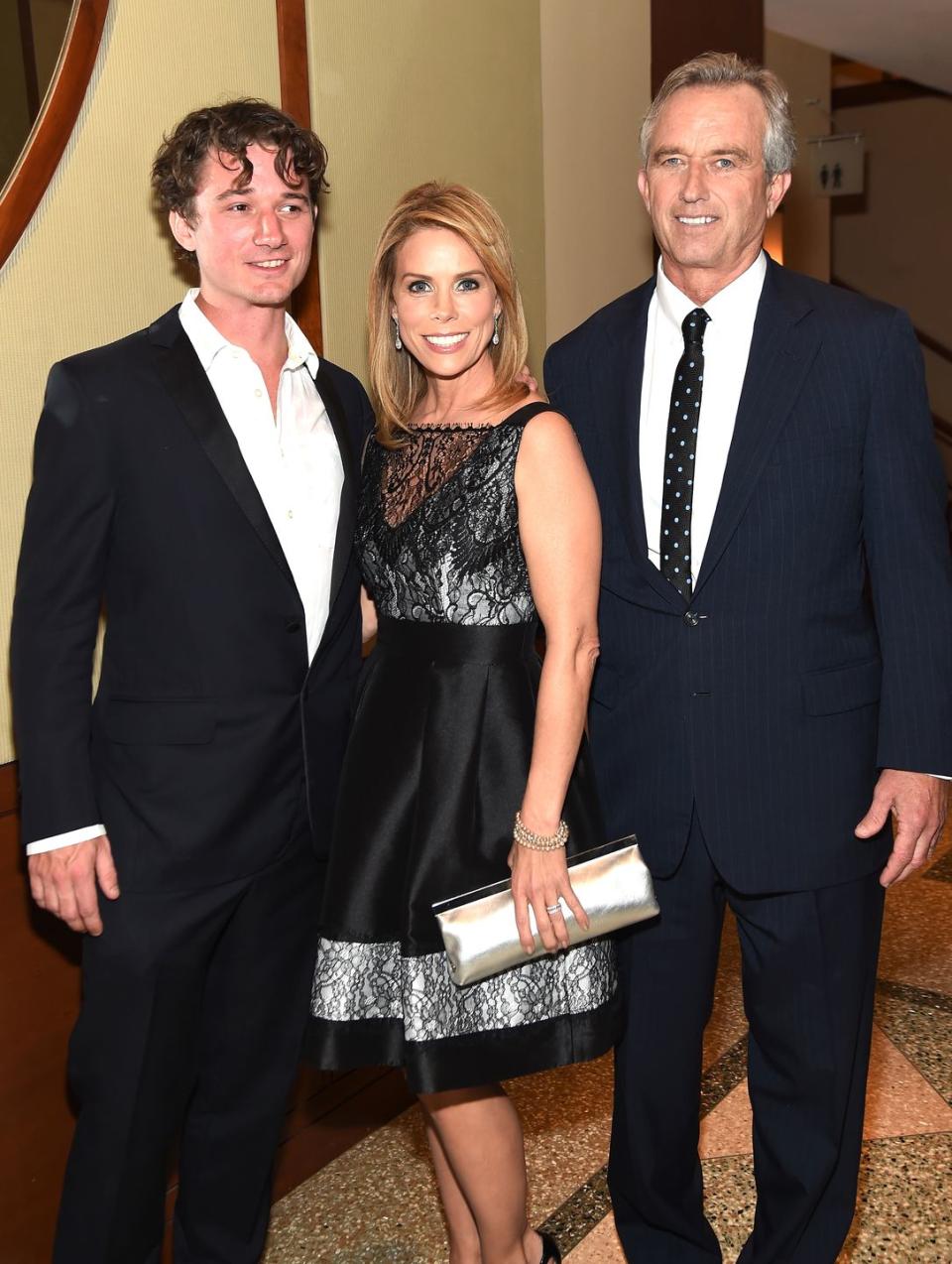

Between them he and his wife, the actress Cheryl Hines, have seven children. Six are Kennedy’s (two with his first wife, Emily, and four with his second wife, Mary, who died in 2012, after they were separated); one is Hines’s daughter from a previous marriage. It is mid-August and five of the kids, all between the ages of 16 and 25, have been at the house for the whole quarantine. Everyone’s on a different eating schedule, it seems. The men grill a lot of meat. There is the occasional tension about dirty dishes.

At least there aren’t many animals at the moment—just the dogs, one of them a rescue pit bull, and some tortoises. They don’t have the emu anymore.

The room that Kennedy, who is 66, uses as an office is walled with books on shelves stacked six high from floor to ceiling, hundreds and hundreds of books. On top of those: a long line of framed photos like cars on a freight train—old ones, recent ones, black-and-white, color. A sprawling L-shaped sofa with blankets and pillows, a big TV.

One sunny day this summer, Kennedy’s niece and her husband came by with her kids for a swim, and everyone was out in the backyard. Except Hines, who was scheduled to participate in the reading of a new play via Zoom.

She was in her office overlooking the pool, in the middle of the reading, when she suddenly heard a scream—high, loud, shrill, suggestive of catastrophe. She looked out the big windows and saw kids running everywhere, grownups chasing them, people grabbing their hair, people jumping into the pool—and heard the unending scream, which had multiplied to more screams.

“The dad has two of the toddlers under his arms, and there’s another toddler screaming and they’re all screaming. And Bobby’s running around, the dogs are barking,” Hines says. “I’m thinking, Do I need to stop this and call 911?”

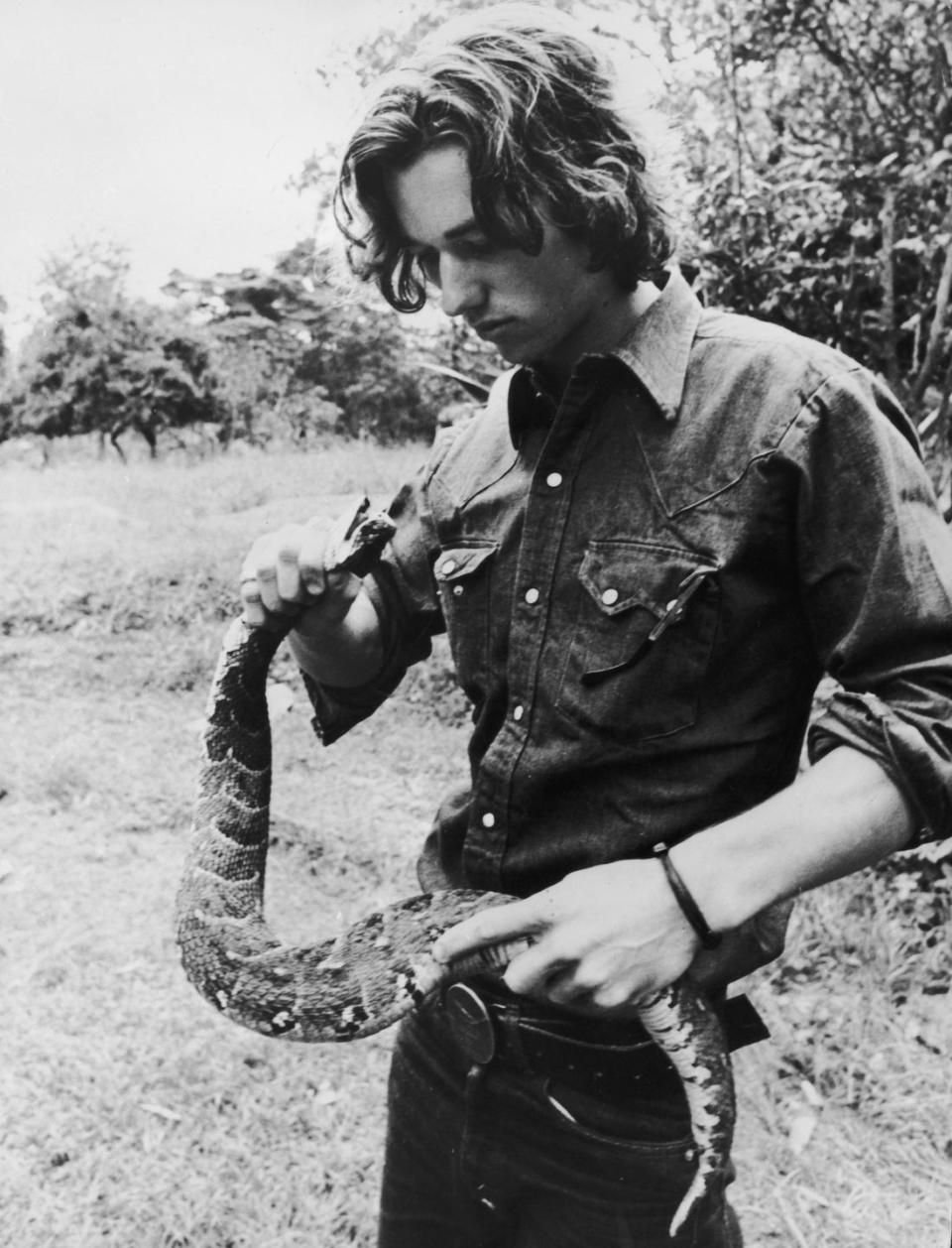

But in the back of her mind she knew that Bobby would know what to do, because he knows what to do in these situations. He’s an animal person. Like that time not long ago when he was hiking with their friend Michael Baum, a lawyer Bobby has worked on cases with and who used to be his neighbor in Malibu, and they saw a rattlesnake. “We’re going along this hike with his dogs, and he sees a rattlesnake right in the middle of the path. He says, ‘Michael, get your phone, get a picture of this snake—here, take my phone, take it,’” Baum recalls. “I’m worried about Bobby, because he’s leaning down within a foot and a half, getting his head down there, ready to grab and catch the snake so he can hold it up and get a picture of it. The look on his face while he’s catching it, with a smile, and the delight he has in doing things in nature, is hilarious and charming.”

It turned out that in the backyard during Hines’s reading, someone had accidentally knocked a bee’s nest, and the bees were stinging everyone. But Hines saw everyone begin to calm down—Bobby calmed the dogs. Bobby tended to the children. She took a breath and turned back to her reading, quickly trying to find her place.

Bobby knew what to do.

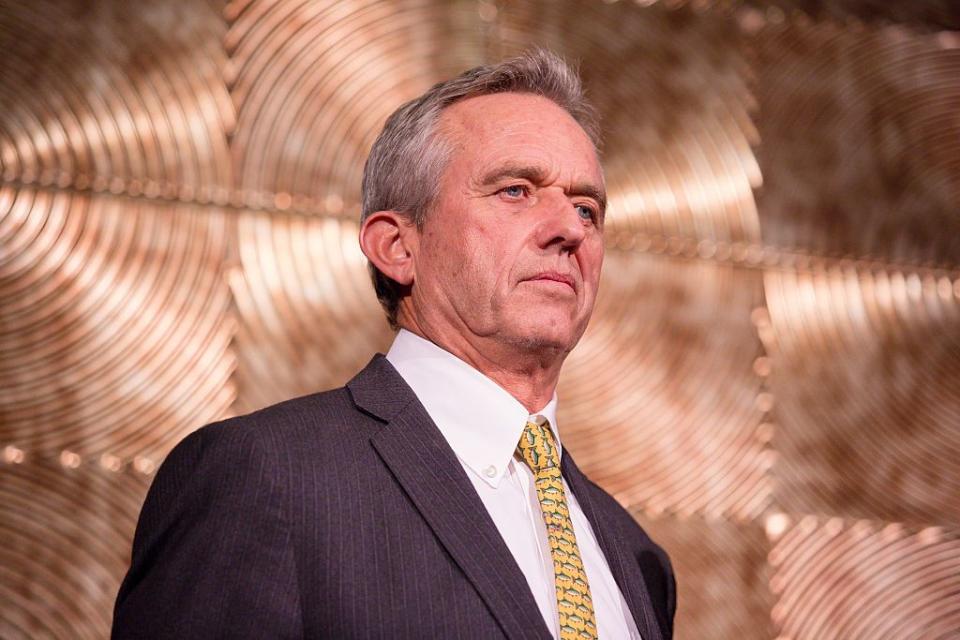

He is not an easy man to talk to.

Not because he is hard to reach (he isn’t). Not because he is smarter than you (which he is). He is hard to talk to because there is only one subject he really wants to talk about.

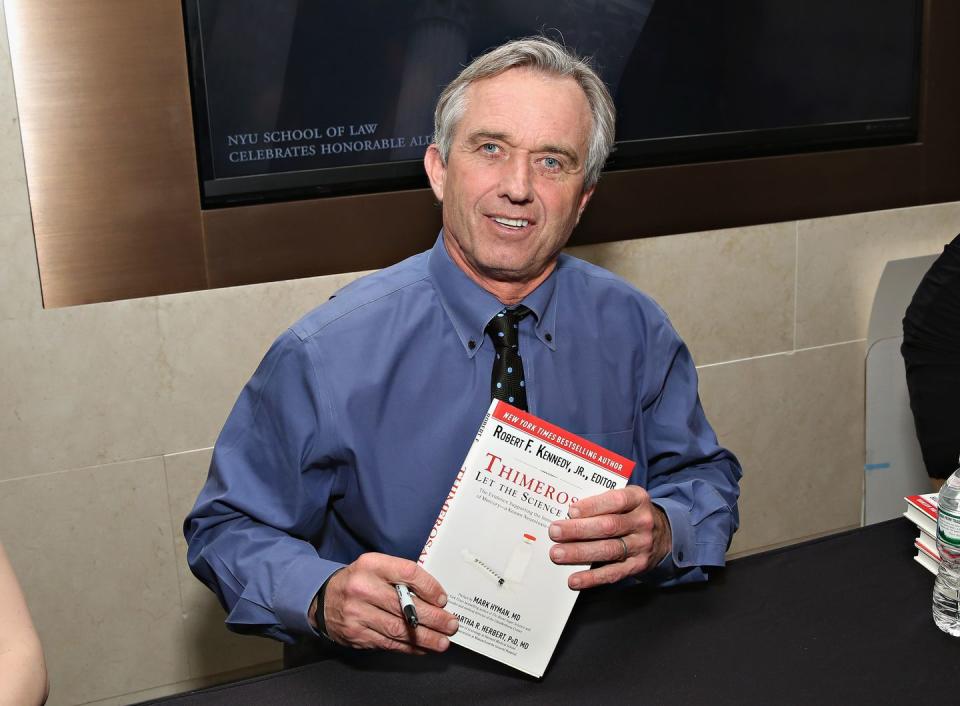

It’s not the bee incident. Or life in quarantine. Or Biden or Trump or his pit bulls. When you talk to Bobby Kennedy Jr., much of what you end up talking about is studies and statistics and, of course, vaccines. It is the preemptive subject of almost any discussion. He has a kind of hoarder’s wall of journal references and esoteric studies and dense spreadsheets of data, which you have to climb over and around to reach him.

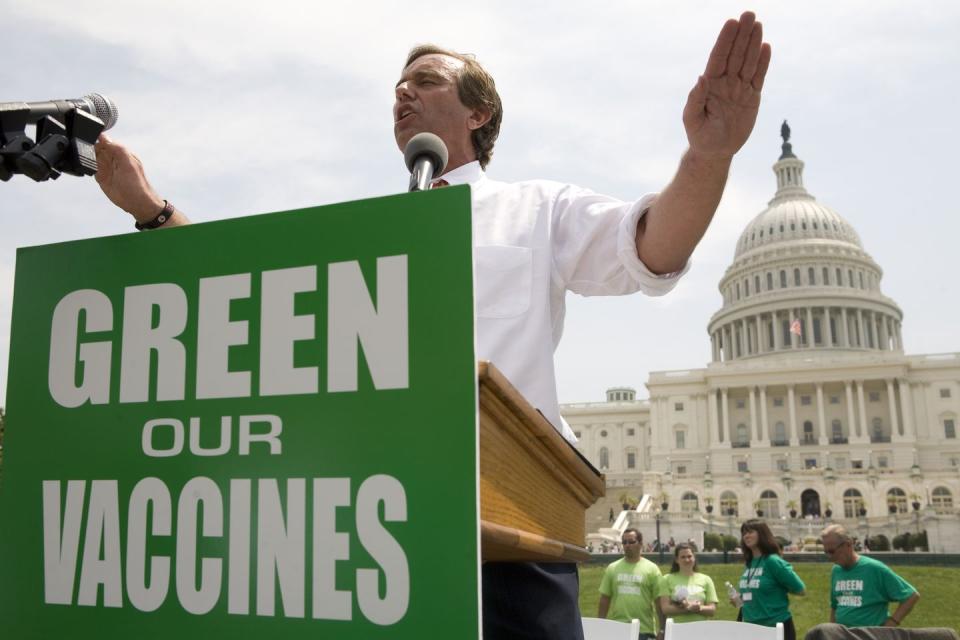

He insists, famously, that most vaccines pose a grave danger to public health, causing everything from autism and other intellectual disabilities to allergies to cancer. He is equally skeptical of the dangers of any of the potential Covid-19 vaccines.

Even when you try to steer the conversation into areas of humanity or hobbies or history, you often end up back in an obscure scientific journal or a questionable tale about Jonas Salk or a screed against Anthony Fauci.

On this subject, I think he is dangerously wrong. But that’s not the most interesting thing to talk with him about, nor is it the subject of this story. You can judge his arguments for yourself on your own time. The debate about whether vaccines are safe rages every day, and you can go online and read studies and opinions on every side. You can read almost any story by or about Kennedy and you will encounter the substance of his beliefs in detail. There aren’t many doctors in the world who think it’s a debate at all, of course.

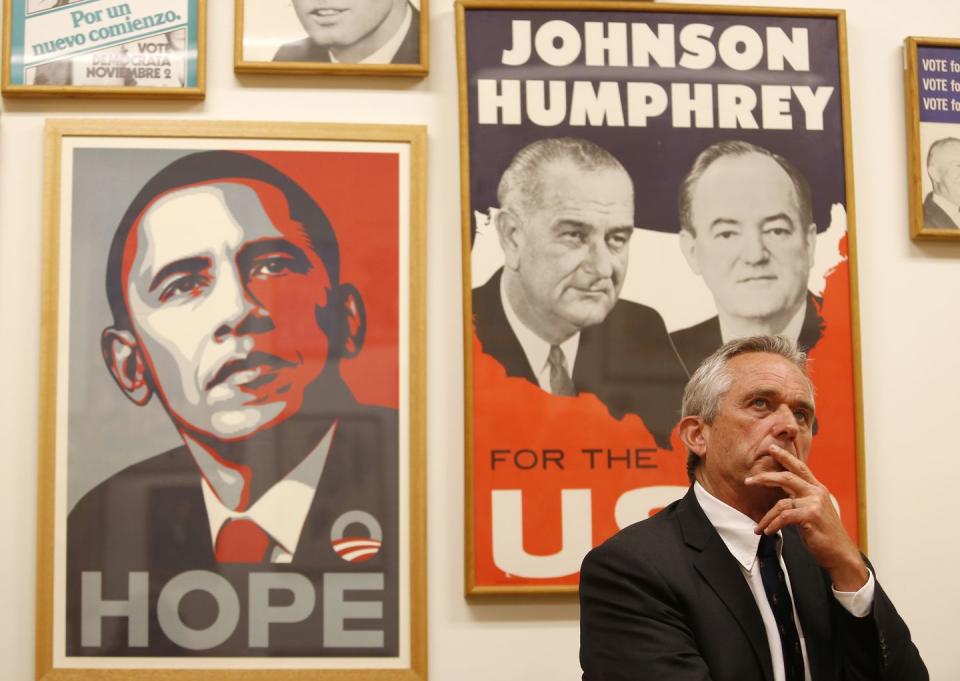

A deeper question than whether he’s right or he’s crazy is why Bobby Kennedy Jr. is doing any of this. There was a time when he was almost universally admired, a fighter for conservation and the environment—perhaps the dominant issue of our time—and a shining figure worthy of his family’s legacy. Now he is shunned by many of his former allies and admirers, ignored by much of the once fawning media, and just tuned out by many who are uncomfortable with his sometimes hectoring obsessiveness.

How did he get to this place? He is unbending in his views on a subject that is, at best, in severe dispute, and that has made many of his own friends, even some people in his own family, dismiss him as uninformed and dangerous.

What is it about his life so far that has made him so willing to be considered, well, crazy by so many?

The bee incident—kids running around, bees stinging, dogs barking, tortoises inching along somewhere in the bushes, everyone back in the pool afterward—could have played out at Hickory Hill 60 years ago.

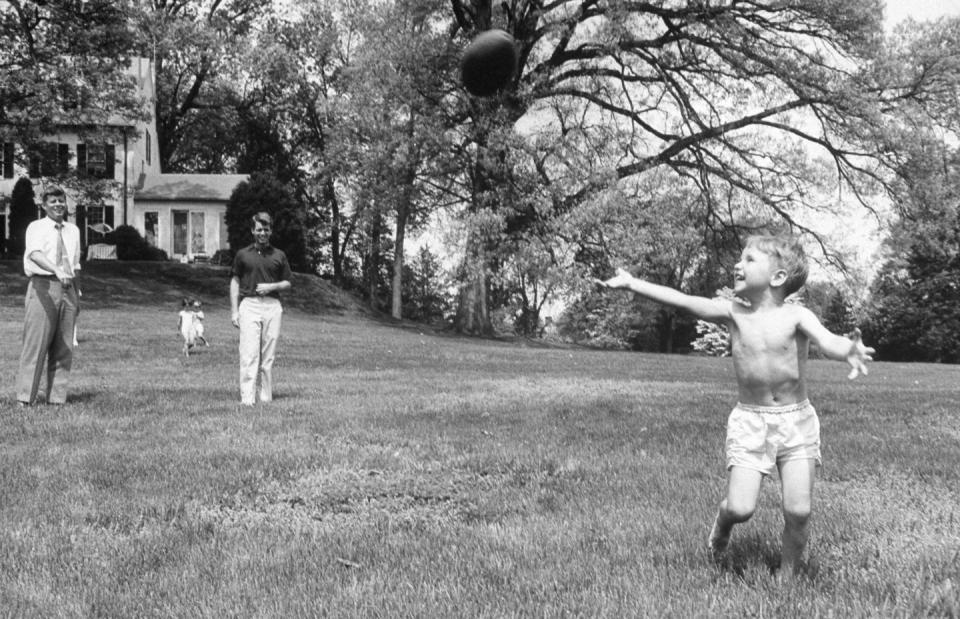

Hickory Hill was a kind of farm, six acres outside Washington, DC, in McLean, Virginia, where Kennedy grew up. His uncle Jack and aunt Jackie had bought it in 1955, when Jack was a senator. A year later Jack sold it to his brother Bobby and his wife Ethel, who would fill it with 11 children.

At Hickory Hill Bobby played among horses, dogs, turtles, pigeons, a pig, and other animals. Bobby was comfortable with wild things.

He loved wild things.

His uncle Jack was the president of the United States by this point, and Bobby got to meet with him in the Oval Office to talk about nature. The president arranged for his nephew to meet the secretary of the interior, Stewart Udall, an environmentalist. Bobby brought his tape recorder and told the man he was going to write a book about pollution and the bad people who do it.

When he grew up, Bobby did write that book. After graduating from law school in the early 1980s, he began his career by questioning anyone who would do harm to nature and he would hold them accountable.

But Bobby had no kind of boyhood, that much can be said.

The early years at Hickory Hill were fun, with the animals and all the kids and the parties and Uncle Jack popping over from the White House with William O. Douglas, the Supreme Court justice, for a swim. He knows he’s had a privileged life, and he uses that word. The money, the fame, the special treatment that being a Kennedy affords.

But, of course, there was more to it.

His Uncle Jack was murdered when Bobby was nine, and like the whole world, he saw it on television. After that his father was distant for a good while, walking alone in the yard with their sheepdog, speaking more softly than he used to. Sometimes not speaking much at all.

And then his father was murdered when Bobby was 14, and like the whole world, he saw that on television, too. The two most important men in his life died while doing what they thought was right for the world.

Bobby never talked much about his father’s murder, says Pete Jenny, who met him at Millbrook, a boarding school in upstate New York, and became a lifelong friend. But he talked about politics—he had views on major issues that Jenny had never thought much about. And Jenny says Bobby’s views were clear: “You knew that he was a kid who was always sticking up for the underdog. Boy, if he felt something was wrong, forget it. He’d fight anybody tooth and nail, often at his expense. That’s worth a lot.”

Millbrook had a bird-banding program, and the students used climbing spurs to get up into tall trees to put bands on young red-tailed hawks and great horned owls. “I can remember Bobby vividly, really a gutsy kid—but a little wild,” Jenny says. “The climbing spurs are dangerous, and these trees are really high. It was hard work, and I remember him going up a tree a little faster than he probably should have, and coming right down twice as fast… If you played with Bobby, you could get hurt. He was that kind of guy.”

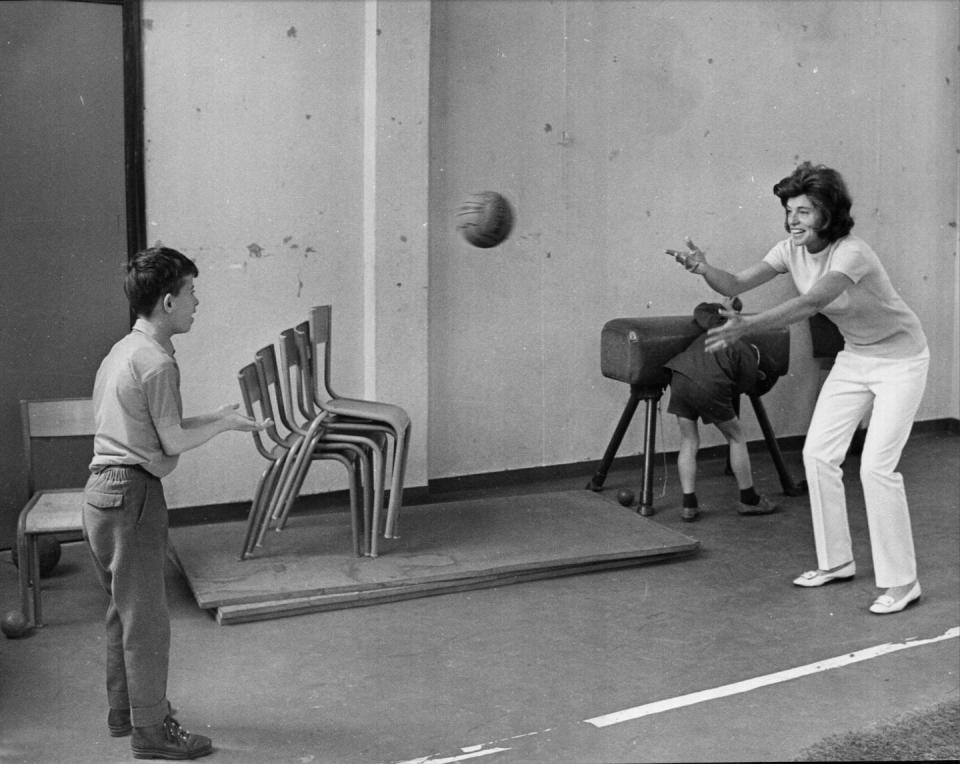

Back at Hickory Hill, Ethel did her level best with the 11 kids, including a baby girl, Rory, born just six months after Robert Kennedy was assassinated. When not at school Bobby used to spend a lot of time at the house of his Aunt Eunice—his father’s sister, and Bobby’s godmother. She ran a camp for children with intellectual disabilities, and she founded the Special Olympics in 1968, and Bobby remembers there always being people at her house who had Down syndrome, “at every meal, virtually. I was always around people with intellectual disabilities.”

Around this time, Kennedy volunteered at the Wassaic State School for the Mentally Retarded, in upstate New York. There he saw mentally disabled adults having sex with each other, in bedrooms and hallways that stank of urine and body odor. He saw children with intellectual disabilities left by their families, uncared for, unclean, unloved. They hid in corners and closets, moaning, masturbating, hungry, afraid.

When he was 15, a year after his father died, Kennedy started taking drugs. He would continue abusing drugs until he was nearly 30, at one point pleading guilty to possession of heroin.

Although he had long realized he had a problem, he says, he couldn’t make himself stop, and while he understands that that is the very definition of addiction, part of him doesn’t understand how it happened to him. He was taking heroin, all kinds of things, and it controlled him. It remains the only time in his life when he felt he couldn’t exert total control over himself.

“I spent a lot of years trying to quit on my own, and not able to—and being baffled by that, because I have iron willpower in other parts of my life,” he says from Brentwood on one of our Zoom calls. “I felt like I could do anything with willpower. I was bewildered that it didn’t work on drugs. I think the most demoralizing feature of addiction, for me, was that incapacity to keep contracts with myself.”

Kennedy got sober in 1983, and he attributes some of his success at this to his first cousin—the son of one of Ethel’s brothers—Michael Skakel, who himself had quit drinking and taking drugs the year before. The Kennedys and the Skakels were never close—the Kennedys were Democrats and the Skakels were oil-and-coal Republicans, and it just never quite worked. But a deep relationship grew between Bobby and Michael as both emerged from addiction, and they attended recovery meetings together, camped, took wilderness trips, and talked and talked and talked.

Kennedy still goes to meetings almost every day.

As part of Kennedy’s community service after his heroin conviction, he found himself working at a tumbledown farmhouse in Westchester County. The owner was a group called the Open Space Institute, and a new tenant would soon be occupying the house and barn: the Riverkeeper Association. It was a new organization, formerly known as the Hudson River Fishermen’s Association, devoted to holding polluters legally responsible for cleaning the water.

Kennedy was at work on the house when a man about the same age named John Cronin showed up. Cronin was at the time newly employed as the first Riverkeeper, responsible for patrolling the river in search of violators of the Clean Water Act.

Cronin hit it off with Kennedy almost immediately. “We both loved a fight,“ says Cronin, who is now the director of the Blue CoLab at Pace University’s school of computer science and information systems in Pleasantville, New York. The fight, he says, was their version of the public trust doctrine, that we are all part owners of the waters, and no one should be allowed a use that alienates the rights of others.

Kennedy became the association’s chief prosecuting attorney, a title they made up, and they went after towns, cities, and corporations that were polluting the river. In one case, New York City wanted to reopen an upstate pumping station that was polluting a reservoir. In a 300-page statement, the city contended that the pumping station did not kill fish by sucking them in through a giant intake pipe, because the fish sensed impending danger and swam around the intake area.

Dozens of people had read the document, but finally Kennedy said, while prepping an expert witness, “Wait a minute. Can fish ‘sense impending danger’?”

“And it absolutely destroyed the 300-page statement,” says Cronin. “That’s not an easy thing to do. You have to have a keen eye and a keen mind to say, where are the holes? And where are the facts that work against the people who are presenting their own facts?”

They soon formed the Environmental Litigation Clinic at Pace University’s law school, combining teaching with bringing down polluters. Kennedy tried hard to keep his name out of the press when they won big cases. “He wanted to prove that these cases could win on their merits,” Cronin says.

Today, as the Waterkeeper Alliance—of which Kennedy remains president—the organization has more than 350 waterkeepers in 45 countries, patrolling and protecting nearly 3 million square miles of waterways. “Bobby’s the kind of guy who walks over to the creek and goes and talks to the first fisherman he can,” says Gary Wockner, the Waterkeeper on the Cache la Poudre River in Colorado. “He gets into long conversations about the health of the creek, what kind of fish are biting.”

In 1999, Kennedy published the book he promised his Uncle Jack and Stewart Udall he would write. Written with Cronin, it was called The Riverkeepers: Two Activists Fight to Reclaim Our Environment as a Basic Human Right.

In 2000, Michael Skakel was charged with first-degree murder for the killing of Martha Moxley, which had occurred back in 1975. Moxley and Skakel, both 15 at the time, were neighbors in the Belle Haven section of Greenwich, Connecticut. Both were among a group of kids hanging out on the night of October 30, at several homes in town. Someone killed Moxley with a golf club as she walked home through her yard.

It is one of the most widely covered unsolved murders in modern American history, and Skakel’s arrest 25 years after the crime was a strange, shocking development. Skakel was found guilty in 2002 and served more than 11 years in prison. His sentence was overturned when a judge ruled that his lawyer, Mickey Sherman, had been incompetent.

Believing his cousin to be innocent, Kennedy took up Skakel’s cause with the same fervor he’d brought to environmental issues. In 2016, as Skakel was awaiting the state supreme court’s decision whether to reinstate the conviction, Kennedy published a book called Framed: Why Michael Skakel Spent Over a Decade in Prison for a Murder He Didn’t Commit. In it he lays out a complicated new theory: that Moxley was killed by two other teenagers, visiting from New York City, a 50-minute train ride away.

His theory was based in part on unidentified hairs found on a blanket on Moxley’s body. Kennedy claimed, among other things, that investigators lost that hair evidence, though the Greenwich police deny losing or destroying any evidence and Kennedy could never substantiate his allegation. In any case, forensic scientists say it is not possible to match hair definitively to specific individuals.

But Kennedy has never backed off his assertion that his cousin was the victim of a system that was sloppy, corrupt, or both. He is emphatic that his evidence is scientific, not based on opinion or insinuation. No forensic evidence—no evidence of any kind, in fact—ever inculpated Skakel in the murder.

Summer of 2013, a cloudless day in July. Classic Bobby.

He and his brother Max are out on Nantucket Sound, on Max’s 65-foot wooden yawl, Glide, with some number of assorted Kennedy nieces and nephews and sons and daughters scampering and sunbathing on the teak deck.

About a mile off South West Rock, between the Kennedy compound in Hyannis Port and the Point Gammon Light, Max spots a large leatherback turtle’s head bobbing off the port side, a bright yellow buoy tethered to its neck, the turtle struggling to keep its head above the waves. Max lowers the sails and he and Bobby dive in, both of them holding knives and pliers, and swim to the animal.

Mariah Kennedy Cuomo—the 18-year-old daughter of New York governor Andrew Cuomo and Bobby’s sister Kerry—is on the boat, filming the rescue with her phone. “Are you okay?” she shouts, and Bobby asks for a line to hold on to. Her cousin Grace, granddaughter of Teddy Kennedy, takes photos.

A fish net is wrapped around the turtle’s head seven times and around both its large fins, “tearing through its skin and incising into its neck,” Max says.

The brothers spend more than half an hour freeing the 500-pound turtle, fighting three-foot seas. The animal seems scared and confused at first, and keeps trying to escape and dive.

When they’ve cut the last line, the turtle, now calm, swims away.

Mariah’s video ended up online, and in a weird twist, Bobby and Max—both licensed wildlife rehabilitators—were called out by the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration for violating laws that prohibit people from touching endangered animals. Nothing happened, no fines, but the NOAA basically said they shouldn’t have done what they did—mostly because of the danger. “You can get entangled, go under, and it can turn into a tragedy,” an official told the Cape Cod Times.

Bobby released a statement acknowledging the danger in messing with a quarter-ton turtle in choppy seas. But he was also startled by the way the NOAA publicly condemned his actions—risking his own safety to help a wounded animal that would have surely died. It was, to him, indicative of institutional forces standing in the way of individual freedom.

“Bobby said to me a long time ago that federal laws are designed to keep people apart from nature, and that they make the experts the only people who are allowed to interact with the animals,” Max says. “It’s sort of like the priests in the Middle Ages, when you couldn’t have a relationship with God. You had to have a relationship through the priest, because only the priest could really understand the majesty of God.”

A few years ago Kennedy took three of his children to the Los Angeles home of a man named Paul Schrade. Schrade was an old man—he’s 95 now—with a full head of white hair and a frank way of speaking.

Robert F. Kennedy would also be 95 today if he had not been assassinated in 1968 at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, with Schrade at his side. Paul Schrade was the director of the United Auto Workers in California and an aide for Kennedy’s presidential campaign.

He was also shot, and injured, in the chaotic exchange that killed Kennedy.

At Schrade’s home, Bobby Kennedy Jr. asked Schrade to tell his children what happened that night. They knew the details of what happened—from their own family, from their father, and because “you can’t be raised in America without knowing” what happened, Kennedy says. “But they didn’t know his details. He was standing next to my father that night. And the clarity of his mind is breathtaking.” Kennedy stood while his children sat and listened, one of them perched on the hearth.

On the way home, the children couldn’t stop talking about what the old man had told them. Schrade believes that the man convicted for Robert Kennedy’s murder, Sirhan Sirhan, did not fire the bullet that killed him. Schrade is not alone in this belief—there is a complicated narrative around what happened, even though it was captured on television—and even some of Bobby Jr.’s siblings have joined him in calling for a reopening of the investigation.

Bobby and others have implicated a man named Thane Eugene Cesar, a Lockheed employee who worked nights as a security guard at the Ambassador. In a 2018 Instagram post written the day Cesar died, a free man in the Philippines, Kennedy noted that he had only gotten the hotel job “about one week earlier” and that when Robert entered the Ambassador’s restaurant pantry, Cesar “grabbed my father by the elbow and guided him toward Sirhan.” He then notes the chronology and number of bullets fired, contending that it was impossible that Sirhan could have murdered his father. And yet, “police have never seriously investigated Cesar’s role in my father’s killing.”

The Los Angeles police have long considered the case closed. Still, Bobby is hardly alone in believing that the investigation of Sirhan was shoddy. His sister Kathleen Kennedy Townsend, the former lieutenant governor of Maryland, has also publicly expressed doubts about the case.

Sirhan Sirhan’s next parole hearing is scheduled for sometime in 2021. “His lawyer called me this week and asked me if I would testify,” Kennedy told me. “And I said yeah.”

Kennedy drives a minivan. It’s a Dodge Caravan, the granddaddy of minivans, midnight blue, and the dashboard is a crosshatch of scratch marks from the dogs. On the floor: the remnants of some T-Bonz dog treats, and what looks like hay. The end of one of the armrests in the back has been chewed into a foamy nub by some dog or another.

When this one dies, he will buy another minivan.

He drives minivans because they’re good for picking up stray animals, things like that. “If he’s driving down the road and he sees an injured skunk, he could pick it up and take it home and try to help it,” says Hines. “You can do that when you have a minivan.”

She smiles. If you’ve ever watched Curb Your Enthusiasm, the HBO show on which she plays Larry David’s wife and which made her famous, you know the smile: big, wide, a little sarcasm around the eyes.

“Our minivans smell like animal,” she says, the grin remaining. “But that’s what he likes about it, that you can pile kids in there and you can pile animals in there. And you never have to clean it.” (His father drove a beat-up station wagon that was also always full of kids and dogs.)

And then there’s the roadkill. “Bobby will be driving along, and if you pass roadkill he will get out of the car and check the skull to see if it’s been injured or crushed. If it’s whole, he’ll take it home and clean it. He has a collection of all the mammals in New England at his house. The children learn so much. But it’s so foul, the minivan,” says Max, 55, one of Bobby’s nine surviving siblings. (David died of a drug overdose in 1984, Michael in a skiing accident in 1997.) “A few years ago, oh my God, a seagull had died, and that was in there for way too long.”

It was his love of nature that got Bobby into the business of fighting polluters in the 1980s, and he says that his work fighting polluters got him into the business of fighting vaccine-makers. He sees this work not just as fighting corporations but as protecting children—perhaps from the same kind of fate he witnessed over those meals at his aunt Eunice’s house all those years ago, and volunteering at the home for the disabled.

I’ve spoken with Kennedy at length about vaccines, and I’ve spoken with doctors who have devoted their lives to medicine—to making children healthy and saving their lives. I’ve seen the consequences for parents to whom he suggests that they may have played a role in their child’s disability, illness, or death. I’ve heard him outline the breathtaking size and history of the conspiracy he believes exists. By inserting himself into the vaccine debate, Kennedy has lost friendships, business opportunities, and influence within the Democratic Party.

“Well, yeah. I lost a lot of friendships and business relationships and collaborators and partners and allies,” he says. “But I’m at peace, because I think this is the most important battle of our age.”

Joe Biden is also a man who has lost a lot in his life. I asked Kennedy if the two Democrats have spoken over the years of their shared experiences. “I used to talk to him a lot more often, but I haven’t…” He pauses, and chuckles pretty hard, and says, “I don’t talk to anybody anymore.”

He would, by the way, take a Covid-19 vaccine, he says, if one emerged that he felt was safe and effective. “Oh yeah, if it did what people think it’s going to do, which is, you know, if you get a single injection, and it was safe, and it gave you protection from Covid for life, of course I would take it, as I think everybody would,” he told me. But he is skeptical. “It’s hard to imagine that they’re going to find—they might! I mean, there’s 140 vaccines out there, and one of them might actually find a magic bullet.”

His positions have also upset his relationships in his extended family. Last year his brother Joseph P. Kennedy II; his sister Kathleen, former chair of the Global Virus Network; and his niece Maeve Kennedy McKean, who was executive director of Georgetown University’s Global Health Initiative when she died earlier this year in a canoeing accident with her 8-year-old son, wrote an op-ed for Politico denouncing Bobby’s views on vaccines. The headline: “RFK Jr. Is Our Brother and Uncle. He’s Tragically Wrong About Vaccines.”

I asked him what family gatherings were like that year, after the op-ed. “I grew up in a milieu where we argued every night at the dinner table,” he said. “We were encouraged to argue and to maintain friendships with each other, all of our family love, so I don’t think it’s had any effect. It’s just that we differ about these things.”

His brother Max said of the op-ed, “I think literally it wasn’t a big deal at all. We argue and discuss things all the time, our entire lives. If you get into a fight on a football field, you leave it on the field. It wasn’t even—that’s not even something that would warrant terribly much discussion.”

Bobby is now in the seventh decade of his life, having lived 24 years longer than his father did—his father, loved by millions, fighting for underdogs, murdered for all the world to see. “My dad, when he came out against Vietnam, had everybody against him,” Bobby told me. “The New York Times, all the labor unions—he ran against Johnson, he had every friend basically abandon him when he ran against the president in his own party. He was called a traitor. If you look at anybody who you admire, from a historical point of view, they all went through periods where—it’s hard to think of somebody who hasn’t, whether it’s Magellan or Winston Churchill or whatever—all of the people you admire in history are people who nobody believed at some point, you know?”

He pauses here, looks down. The backdrop of books and photographs hangs behind him like stage set in a play about an aging novelist.

“I don’t know, I think throughout history, every person you admire are people who had the world against them at some point,” he says. “And, um. So. I feel like I’m really lucky. Because I got really lucky in the woman that I married, being somebody who’s incredibly wise and who makes me feel loved all the time every day, and whose judgment I trust. She argues with me all the time about this stuff, and she has very, very wise criticism. I feel like I have a very strong foundation that I can swing my fists from. And then I have great kids who make me really happy. It’s more than a lot of people have.”

After decades of fighting for cleaner water, he feels he has finally found an even better way to spend his time and his name and his considerable brain power, a battle he feels is more important. And if it means losing some of the broad admiration he once commanded, getting knocked down by critics? In a way, all the better.

“I just grew up knowing that’s what you do. That’s what Jesus did. That was the message of Jesus falling three times on his way to Calvary: It wasn’t that he fell, it was that he kept getting back up again,” he says. “I think that’s what everybody who’s lived a worthwhile life has had—that experience of failure and despair and being alone in the universe. I had that experience early on in my life, in my addiction phase and recovery phase, in ways that I learned a lot of lessons from: about how to be peaceful, and in times when it seems that the causes for despair and defeat are overwhelming, to be peaceful in that space.”

In late August, Kennedy traveled to Berlin, where thousands of demonstrators had gathered to protest, among other things, the encroachment of government into their private lives and what Kennedy terms medical and digital totalitarianism.

He stepped onto a stage before a sea of people. He wore a casual button-down and tie, no jacket. A young man in a T-shirt thanked him, in German, for being there, and then Robert F. Kennedy Jr. gave a 12-minute speech (of which he actually spoke for about six minutes, because there was a translator repeating everything he said in German) in which he spoke out against totalitarianism, Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, Anthony Fauci, 5G networks, vaccines, and oppression. His voice—despite a longtime condition, spasmodic dysphonia, that can cause spasms in the muscles controlling his speech—was strong and clear.

He said that people like Fauci “don’t seem to know what they’re talking about” when it comes to the pandemic, and yet they are “very good at pumping up fear.” And in his next sentence he brought up Hermann Göring, one of the most powerful leaders of the Nazi party. “The only thing a government needs to make people into slaves is fear,” Kennedy shouted to the crowd. “And if you can figure out something to get them scared, you can get them to do anything that you want.”

He went on to say that “they” are “using the quarantine to bring 5G into all our communities,” for the purpose of surveillance and data harvesting.

He quoted his uncle Jack, who stood in this same city in 1963 and declared, “Ich bin ein Berliner!” “All of us who are here today can proudly say once again, Ich bin ein Berliner,” he said, and the crowd loved it. “You are the front line against totalitarianism!”

In closing, he said that Bill Gates is trying to spy on the entire planet, and that “you think that Alexis [sic] is working for you. She isn’t working for you! She’s working for Bill Gates, spying on you!”

The day he got home, Kennedy called to tell me that while the media reported that he was in Berlin talking to Nazis and that there were only 38,000 people at the rally, he was in fact nowhere near the Nazi rally, and at his rally there were between 1.5 million and 3 million people, “the biggest gathering in German history. And it was the most joyous crowd.”

He had to jump off the call, and the next day I texted him asking to resume. “I transcribed your speech,” I wrote, “and I have to say, it’s a doozy.” He called me within a few minutes. At first it was the usual Bobby: Vaccines. Covid. Wuhan. Fauci. Science. He invoked his Uncle Jack. He invoked his father.

I told him that, as someone listening to his speech, it seemed clear that he was equating the Centers for Disease Control to Nazi Germany. “That’s not true,” he said. “That’s the problem. I use language really precisely, and I can’t help how people interpret it.” He talked more about threats to democracy, and more about his uncle, and more about his father. And finally I asked him, Is there something about martyrdom that’s attractive, or alluring, to him? Is having people write you off as crazy kind of like a form of assassination?

At first he chuckled at the question.

“Listen, I take a long view,” he said. “One of the great things about studying history is you get some humility from it. You realize how unimportant you really are in the grand scheme of things. It’s a beautiful thing.”

He again spoke of his righteous father, and how at the end of his life he felt he had nothing to lose and so spoke the truth. “I don’t think I’m being self-destructive,” he said. “I’m also willing to take risk, which is a risk in the belief that if I keep telling the truth, it might make a difference.”

We talked for a few minutes more, his voice staticky from across the country. He told me about a lawsuit he’s fighting this fall, which he’s feeling really good about. Then he said, “I’m just walking into an appointment. Do we need to talk more, or are we done?”

No no, that’s okay, I told him. I think we’re good.

You Might Also Like