Robbed of glory: the forgotten farmhand who uncovered the treasures of Sutton Hoo

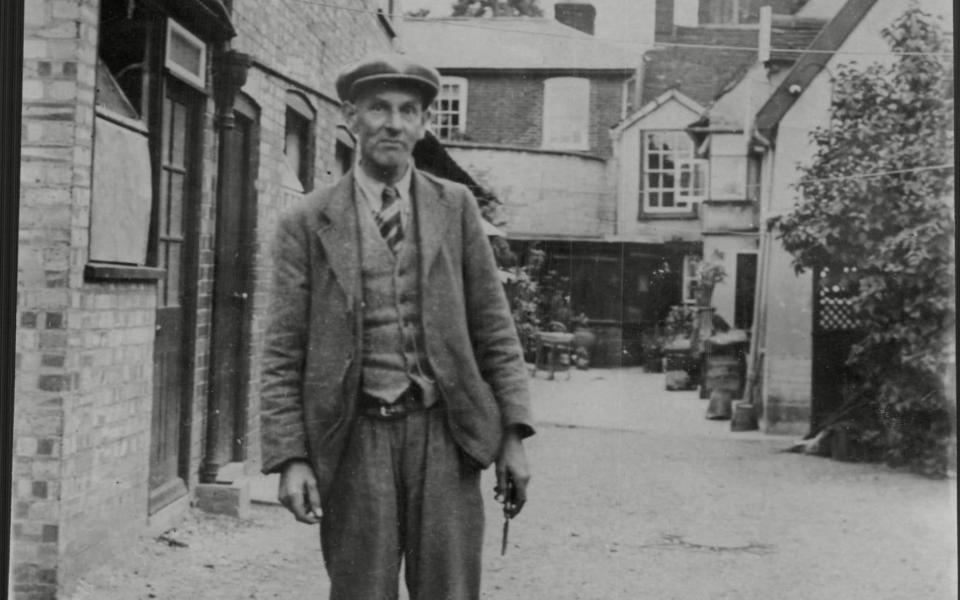

It is August 1939, and atop an ancient burial mound ten miles from the Suffolk coast, an extraordinary chapter in British archaeological history is drawing to a close. Four months after uncovering what the newspapers have called “Britain’s own Valley of the Kings”, Basil Brown, a former farm labourer, milkman and woodcutter, is preparing to leave Sutton Hoo. It’s evening, grass sways, the light is fading.

“I have told Mr Phillips that I expect your work to receive proper recognition,” says Edith Pretty, the owner of the estate, referring to the Cambridge University archaeologist who, ever since arriving at the site, has shown nothing but disdain for Brown’s “amateur” efforts. Brown looks askance - as well he might.

The scene, from The Dig, a new film about the world-famous Sutton Hoo excavation that took place on the eve of the Second World War, has been imagined by British dramatist Moira Buffini. But it is grounded very much in reality. For Brown, the true hero of the excavation and the man who first found the enormous Anglo-Saxon ship that was buried under Mound 1, as well as a 1,300-year-old burial chamber containing priceless treasures, was written out of his own story by Charles Phillips and the British Museum, to whom Pretty gifted the incredible hoard.

Instead, it was Phillips (played with exemplary pomposity by Ken Stott in the film) who was awarded an OBE and the Victoria Medal of the Royal Geographical Society for his contributions to the topography and mapping of Early Britain. Brown, meanwhile, worked anonymously for Ipswich Museum, travelling between archaeological sites in Suffolk by bicycle, until his retirement in 1961.

Now The Dig, which is based on a 2007 novel of the same name by the former Sunday Telegraph television critic John Preston, seeks to re-establish Brown’s place in the history books.

Weather-beaten and given to sleeping under hedgerows to feel better connected to the land, there is no question that Brown - played by Ralph Fiennes in the film as curmudgeonly, socially awkward, but with a winning twinkle in his eye - was far from your typical archaeologist. From a humble background, he had left school at 12 to work on his father’s farm.

But Brown was naturally brilliant. He had taught himself to read and speak four languages, including Greek, by the time he was 16. And he had developed an intimate knowledge of the Suffolk landscape and what lay beneath it. As Fiennes says in the film, “You can give me a handful of soil from pretty much any field in Suffolk and I can tell you whose land it’s from.”

And so, when Pretty, who had moved into Sutton Hoo’s 15-bedroom Tranmer House with her husband Frank partly because of the allure of the 18 burial mounds (or tumuli) that stood in the grounds, finally decided to excavate the site, Brown, then 51, was the obvious man to ask.

What The Dig conveys beautifully is the excitement that built around the site as the true extent of the find became apparent. The excavations started with Brown working alongside Pretty’s gardener, gamekeeper and another estate worker (Frank had died of stomach cancer in 1934). They initially opened three of the smaller tumuli, finding a few artefacts of uncertain origin. Then, after encouragement from Pretty, they took on Mound 1, the largest barrow.

It was here that Brown discovered a small piece of iron, which he identified as a ship’s rivet. The men, progressing with painstaking care and without any of the technology that would be used in a dig today, slowly uncovered more of the rivets, each of them still perfectly in place, outlining the shape of a huge 89ft-long ship that had, Brown surmised, been dragged from the nearby River Deben sometime in the 7th century and been buried to carry a king into the afterlife.

It was the largest buried ship ever found and, as Brown acknowledged to his wife, May, in a letter, the discovery of a lifetime.

And that wasn’t all - as far as he could tell, the mound had never been robbed, and if that was the case, it was possible that there was still an intact treasure chamber in the middle of the ship. Sure enough, after several weeks’ more work, Brown broke through to what appeared to be the remains of a container.

It’s hard to overstate the importance of the hoard that was uncovered beneath the tumuli at Sutton Hoo. Among the 263 dazzling treasures were weapons made of gold, silver and bronze, many of them beautifully crafted and several originating from the Mediterranean, Scandinavia, Egypt and beyond.

The Sutton Hoo helmet is perhaps the most iconic of all Anglo-Saxon artefacts, an object whose extravagant beauty shines like a shaft of light out of the Dark Ages. There’s also the Anastasius Dish, a silver platter hailing from Byzantium. It’s not certain who is buried in the ship at Sutton Hoo – most scholars have suggested that it’s the grave of King Raedwald of East Anglia - but the find fundamentally changed our understanding of our Anglo-Saxon forebears.

The quality of the jewellery alone revealed that these people had been extremely sophisticated, while the stamps on the silver dish proved that their trading routes stretched as far as Constantinople.

“Crude folk in mud huts did not create that armour,” says Alex Burghart, one of the world’s leading experts on Sutton Hoo (and also the MP for Brentwood and Ongar). “The moment that you accept that this is a highly sophisticated physical culture, you then acknowledge that they may well have been sophisticated in a host of other ways.

“The Dark Ages, although we don’t know all that much about them, were clearly, at least at one level, an integrated and connected society which took pleasure in the wealth of neighbouring cultures.”

Unhappily, Brown never got to explore the treasure trove in any detail. As soon as the importance of the dig became apparent, first his superiors at Ipswich Museum, and then Charles Phillips and the British Museum, swept in to steal his glory, and Brown was relegated to a menial role. In the film, he retreats into a kind of pained aloofness as the team unearth more and more astonishing treasures.

But, as well as telling the story of Brown and Pretty, The Dig is also a war film. One of the reasons Brown was pushed aside so ruthlessly, we are told, is the imminence of the Second World War, and the pressure all felt to finish the excavation and secure any finds before hostilities commenced.

The film is also about the “timelessness of invasion fear” says the historian Tom Holland, who stresses the mystery of the burial mounds and the possibility that they housed not a local ruler but rather a foreign interloper.

“The ambivalence of Sutton Hoo is all about asking whether this was an embodiment of England or an invader,” he says. “So then you come to the helmet and it expresses the ambivalence perfectly, because it can look very different if it’s on the head of someone protecting you or someone attacking you. Is Raedwald the face of a Nazi or the face of the Home Guard?”

Alongside these grander themes there is the story of a gruff, solitary man and his exclusion from the story of our greatest Anglo-Saxon find. As Alex Burghart says: “All Anglo-Saxonists are deeply indebted to Basil Brown - almost entirely self-taught, he was an exceptional amateur whose enthusiasm and attention to detail meant that Mound 1 was both explored and preserved. In the hands of another, it might not have been.”

The Dig will be released in select UK cinemas on Jan 15 and launches on Netflix on Jan 29