Rob Harvilla, ‘90s Authority, Picks the Best Rock Year of the '90s

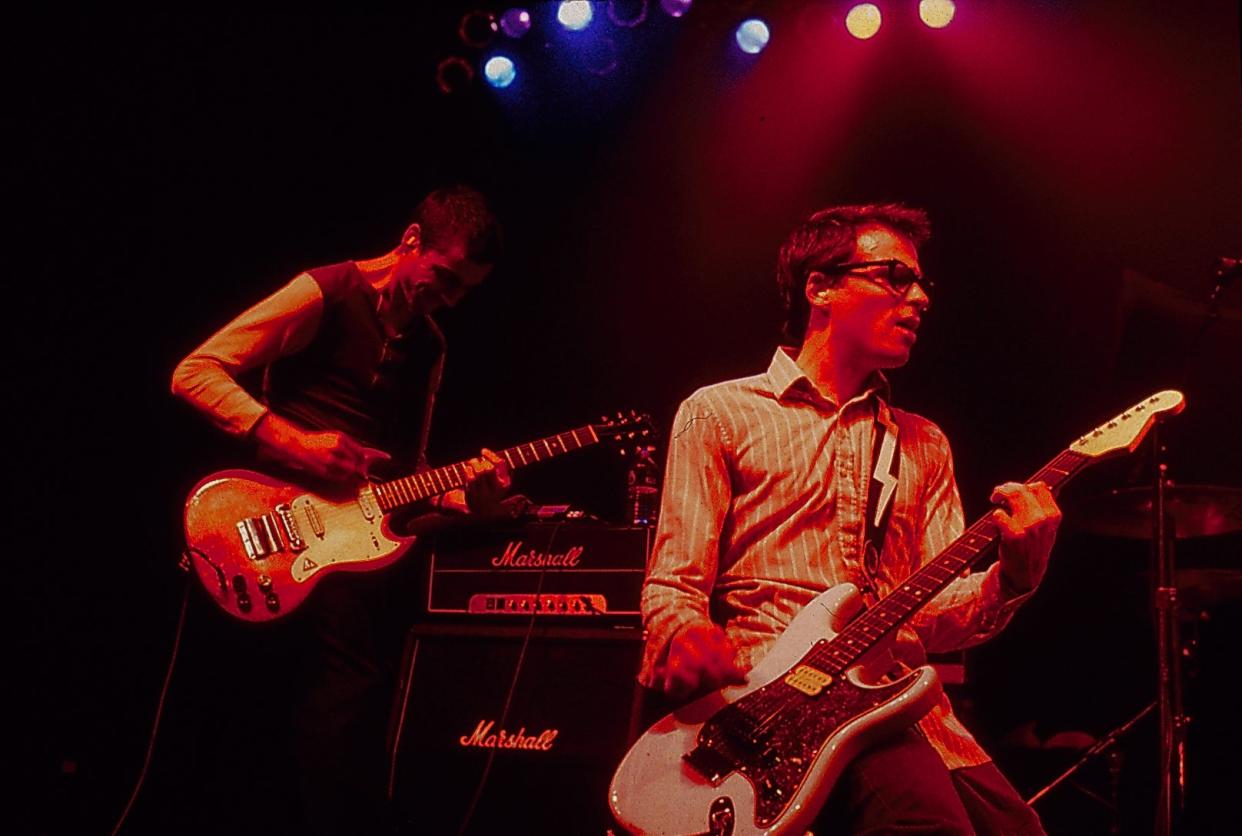

Ebet Roberts/Getty Images

Let us now run a flannel up the flagpole in praise of Rob Harvilla’s 60 Songs that Explain the ‘90s, an instant-classic work of rock criticism worthy of the transformative, nonsensical, unpindownable decade it somehow manages to encapsulate. It gets crazy with the Cheez Whiz; it cooks the breakfast with no hog; it explains the songs that remind you of the good times, and it explains the songs that remind you of the better times; it believes in life after love. A print companion to Harvilla’s Ringer podcast of the same increasingly-inaccurate name (110 episodes and counting), it’s easily the year’s funniest music book, but also the most critically-incisive, the most egalitarian, the most fearlessly quasi-autobiographical, the most generous and humane. (Read an exclusive excerpt right here.)

The most contemporary, too—the ‘90s have never been further away than they are right now, but as a culture we’re working harder than ever to atone for and comprehend them, from the national reckoning over how dirty we all did Britney Spears to the jokes in Barbie about Matchbox Twenty and mansplaining Stephen Malkmus fans. Harvilla’s book feels like a part of that same historical process; it doesn’t leave out already-canonized epoch-definers like Kurt or Alanis, but it gives the same weight to the out-of-nowhere brilliance of Mannie Fresh and “Particle Man,” to the brilliant-stupidness of “Pretty Fly For a White Guy” and Third Eye Blind, and even Limp Bizkit emerging from a giant commode, because all of it meant something to somebody.

“Either it wasn’t that deep,” Harvilla writes at one point, toward the end of an inspired riff about—of all inspiring things—the song “Stinkfist” by Tool, “or it was bottomless.” The great noble truth this book understands is that the best ‘90s music was always both.

Harvilla's book is in stores now; he spoke to GQ over Zoom in early November.

GQ: Craig Finn of the Hold Steady has written and talked a lot about the idea of “rock and roll before the Internet,” when information about your favorite bands was harder to come by and rumors filled in those gaps. This book feels to me like an ode to the very end of that time, when people—especially young people—learned about music from MTV and Rolling Stone and maybe Spin and Vibe, and that was it.

ROB HARVILLA: Yeah. When people are like, Why the Nineties?, my glib answer—which in time became my very sincere answer—is, I was a kid in the nineties. I was a teenager, I was in high school and college. Of course I'm going to love this music more than I ever love any other music for the rest of my life, because that's how it works. But when I try and drill down on what sets the nineties apart, I do think we get to the fact that it's the decade right before the internet atomizes everything, before Napster destroys the music industry as I understood it. I cannot explain to people how important MTV was to me and to everybody. They're like, The TV station that plays Ridiculousness 23 and a half hours a day? Yes. MTV was everything to me in the Nineties.

I was raised by MTV, from whenever it started to 1996 when I went away to college, and it was marching orders. Winger is very cool. I’m like, Yes, I agree, Winger is very cool. The next day: Nirvana is very cool and Winger is the worst band. Yes. I agree with that completely. I walk into junior high the next day with my Pearl Jam Stickman T-shirt and my flannel and I'm all in on the alternative rock revolution, and that's down to MTV, that's down to the alt-rock station in Cleveland where I grew up. It’s me standing in front of a wall of CDs at Camelot Music with $20 in my hand like, What's my new identity? Is it Pablo Honey? Is it Bandwagonesque? I try and explain these things to young people now, and I even try and explain these things to old people like me now, and we don't even believe it was actually like that anymore—but it absolutely was.

So were the ‘90s actually the last cohesive decade, or are they just the last years we can collectively get our minds around, because we didn’t have a limitless Internet’s worth of information and options coming at us every single day?

I still go back and forth on the idea of the monoculture—the insistence that everyone was listening to Thriller in 1983, or that everyone was listening to Appetite for Destruction in 1989. In some ways it sounds like bullshit to me—but it’s true that whatever was on MTV was what was popular, and I just bought into it wholesale, and I feel a nostalgia for that. People say it was harder to get into music. You had to go out and find it and find the cool things and track down the imports or whatever. But it was also easier. You could just take whatever was fed to you and convince yourself you loved it, even if you didn’t, necessarily. But I think Jann Wenner, for example, recently sort of revealed the limitations of letting a precious few people determine your worldview when you were a teenager and the stuff you have to unlearn about that, even if you only learned it subconsciously.

The 90s do feel cohesive, though. I try and filter out my personal nostalgia and I try and filter out the whole pre-Internet element of it, but it does feel like the Macarena could only have happened in that moment, that “Achy Breaky Heart” could only have happened in that moment. Or “Smooth.” Every generation, every era, every year has its fluke hits and its out-of-nowhere sensations, but it all just felt different back then, and I'm still trying—after 110 episodes, after 600,000 words of monologuing, after 85,000 words of a book, I still can’t quite articulate why that is. The “explains” in the title has always been a joke and it remains very much a joke, but you'd think by now I would be able to explain it, even as a joke, and I still can't. But I love it for that. I love the unknowing part of it.

When people talk about “The Nineties,” as an era with specific cultural signifiers, they're really talking about the early ‘90s. It feels like there's almost a generation gap within the decade, between the grunge ‘90s and, say, the Spice Girls ’90s.

The chart that I talk about a lot—and it freaks me out every time I look at it—is a list of the top 10 most-played songs on modern rock radio from 2010 to 2020, and they’re all from 1990 to 1994. It’s Green Day, Nirvana, Alice in Chains, Pearl Jam, maybe one or two others I’m forgetting. Of course this is classic rock now, and that breaks my heart, it makes me feel ancient—but it still feels like modern rock. It feels like that's when rock peaked and or died, right in that little stretch. I don't know if the dividing line is when Kurt Cobain passed, necessarily, but from there Green Day sort of takes over and you have this bright, happy pop-punk moment. The Offspring.

But then you're getting into nu-metal, then you're heading toward Woodstock 99, and there's ska. The way ska blew up on my midwestern Ohio campus for nine months, from 1996 to 1997—I was in a ska band. I played bass in a ska band. How did that happen? It gets very bizarre and not nearly as cohesive after 1994. When I look at all the episodes that I've done, I’ve done a few songs from 1990 to 1991, I’ve done a few from ‘98 to ‘99, but the core of it is right there, in that Gen X sweet spot, those few years when alternative rock was everything, when the Wu-Tang Clan and A Tribe Called Quest were around. That was our generation. We just lived it on fast-forward for three or four years there, and that was it, and it was enough.

To your point about classic rock: It’s wild to watch the collapsing of ‘90s rock, with all of its factions and subcategories, into this one monolithic thing. Green Day are doing a world tour with Smashing Pumpkins opening. As someone who remembers those bands when they were new, and what they signified, that’s an impossible bill to wrap my mind around.

The example that I always think of is, I was supposed to go see Soundgarden like three days after Chris Cornell died. He was going to play a giant rock festival in a soccer stadium in Columbus. Soundgarden were going to be the headliners. And they get this news and the festival is scrambling to replace them, and they can't, really, but Bush played, and Gavin Rossdale sang “The One I Love” by REM in tribute to Chris Cornell, and I just could not process that. My inner 13-year-old just could not understand what those three bands had to do with each other, because back when I was 13, those were three different distinct universes in terms of integrity, in terms of talent, whatever. Just the context-collapse of the thing, right? People have been doing ‘90s package tours—they get Fastball, they get the Wallflowers, Sugar Ray. The way all that music just becomes “Nineties music” the farther you get away from that decade—that’s a fascinating creep to me, and I like interrogating it, but celebrating it at the same time.

That’s what I love about the book, and it’s what I’ve loved about the show. You’re taking things that, at the time, might have seemed inconsequential in the giant shadow of a band like Nirvana, and you’re giving them the same kind of intellectual attention.

One thing that really struck me in Everybody Loves Our Town, the grunge oral history that Mark Yarm wrote, is everybody hated Candlebox so much. The first wave of grunge happens, and everything blows up, and then the next band out of the chute is Candlebox in ‘95 or ’96, and it’s These guys are posers, these guys are terrible. They're just the biggest losers imaginable. I felt so bad for Candlebox. And then I remember driving around the suburbs of Ohio blasting the guitar solo to “Far Behind,” and it just felt like “Don't Stop Believin’” in that moment. It was just the greatest thing ever. I wanted to be a rock critic since I was 13. I grew up on Rolling Stone, on Spin, on all of it, and so I had this built-in elitism, or elitism-in-training, from the very beginning, but I do really love that song. What I know critically bumps up against what I knew emotionally when I was 12, and what I knew emotionally back then was Candlebox were just as good and just as important. A Seven Mary Three were going to last every bit as much as Alice in Chains.

I think this is what I've always loved and also what has always infuriated me about your writing is how much access you have to your humanity, and in this case your authentic 13-year-old humanity. It takes me many drafts to sort of replicate that kind of organic response to things.

That is very kind. I feel human most of the time. I'm trying. I think it's just that I remember things. I forget where I put my keys, or what kind of car I drive, or phone numbers, but I can remember the song I was listening to when I passed this intersection in 1990 after getting my teeth cleaned. Random songs and spectacularly, insultingly mundane settings just refuse to leave my memory and crowd out all sorts of other far more salient and important information, and this is just the way my head works and I'm trying to make it work for me. I'm trying to turn it into content.

OK, so, impossible question: What year of the ‘90s is the most “‘90s” year? If you had to put one year in the time capsule, to stand in for the whole decade…

I guess I have to say ‘94. I was torn between ‘94 and ‘97, but I'm going to pick a side and say ‘94. It feels like the peak. I grew up an alt-rock kid. I was tribalist. I was on a limited budget. I picked a lane and stayed in my lane back when you had to stay in a lane, and so that meant my favorite five bands in 1994 were Smashing Pumpkins, Nine Inch Nails, Pearl Jam, maybe the Afghan Whigs, and They Might Be Giants. Pavement were exotic, by my standards, at this time of my life. I think I asked my friend to boost Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain, the cassette tape, from the super Kmart. Shout out my friend Scott. I was too much of a goody-goody to actually shoplift myself, and so I outsourced the shoplifting to my friend and he boosted it. I think it was actually in one of those anti-theft giant cases that make it harder, but he did it. He managed it. Thank you, Scott, for that.

Weezer’s “Blue Album”-- that’s 1994. 1994 is when Nirvana-mania peaks. Pearl Jam are starting to pull away from rock stardom, but they haven’t pulled away yet. And when you get Dookie, you sort of get a glimpse of what’s going to come immediately afterward, but ‘94 is the last moment where it feels like this could last forever. In retrospect, this is where it peaked, where it ended, and then it sort of atomizes, and cool stuff is always happening, but it never feels that cohesive and generational again the way it does in 1994, when you can listen to Superunknown or whatever and feel like, This is my music, and it’s going to be on top forever.

It’s funny that of those bands you just mentioned, the only one other than Nirvana that really seems to still be picking up new fans every year is Weezer. I don’t know if I would have bet, in 1994, on that being the case almost 30 years later.

Yeah. I mean, I would not have told you that Blink 182 were still going to be playing arenas with exorbitant aftermarket ticket prices in 2023. The whole value proposition of them at the time was like, This can't possibly last. These people are going to spontaneously combust with a spectacular sort of farting noise at any time, so enjoy it while you can. So that one’s really surprised me. I guess Weezer surprised me. The way Pinkerton went from this pariah album to defining that time and that generation, and now there are entire genres of music that seem to be based off trying to replicate Pinkerton, and that saga playing out in real time, where it comes out and everybody hates it and now Rivers hates it, and then everyone realizes that they love it, but Rivers still hates it, and you go through this years-long saga, and suddenly I'm on NPR talking about Weezer covering Toto’s “Africa” because somebody on Twitter told them to.

In 1994, I would not have imagined Rivers Cuomo as the most complex and varied and baffling rockstar personality in 2023. It would not have surprised me then that Billy Corrigan is still talking shit and having way more shit talked about him in 2023. That clearly seemed to be his deal, even back then. But just the depth, the anguish and the complexity of the Weezer arc has just been fascinating to watch as it unfolds. Because I remember—and again, unfortunately, I don't know what I forgot to make room for this—but I remember hearing “Undone (The Sweater Song)” for the first time, in Baltimore on a trip with my family, just driving around, and being like, This is incredible, but I didn't think that it was going to define this decade for the next 30 years. I would not have picked Weezer to be the band that endured to anywhere near the degree that they did, even if nobody likes any of their last 10 albums or whatever.

I think you’ve just posited a few answers to this question in your answer to the previous one, but if you had to name somebody other than Kurt Cobain as the “most ‘90s” person of the ‘90s, who would it be? Who’s the person from the Futurama frozen-head museum that you’d thaw out to talk about the decade?

I’ve had Biggie in my head for a few weeks. That's partially because of an upcoming show that I’m doing, but I go back to Biggie a lot. Just the shadow he casts. Those are always the most intimidating figures to write about—the tragedies, whether that's Biggie, Aaliyah, Selena, Tupac of course, Kurt Cobain of course. Chris Cornell. The larger-than-life, deified pedestal figures are the ones that really intimidate me. So what I try and do is rehumanize them, let them be just normal people who hadn't yet made it, who were still excited, who weren't jaded yet, who weren't painted into murals yet or whatever.

Missy Elliot still stands apart. The music she made in 1997 still feels futuristic. There are plenty of artists who were ahead of their time, but time’s caught up to them, to some degree. They predicted the future and then the future transpired. It doesn't feel like we've gotten to the future Missy Elliot was predicting in 1997 yet. Bjork is like that, too, but Missy stands apart. She’s in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame now. It’s entirely deserved, but it doesn't come close to encapsulating how great she is. It’s a weird feeling, but it feels like damning with faint praise, to put her in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. The hall that she belongs in hasn't been invented yet.

You really pull out some incredible details in this book. I had forgotten that Dennis Franz was in the Chicks’ video for “Goodbye Earl.” We don’t really talk enough about the cultural footprint of Dennis Franz, who was also naked on NYPD Blue, breaking a barrier for network television.

The “Goodbye Earl” video—I have never had that reaction to anything else that I've watched over the course of doing this. I cried watching that video, because I couldn't process what I was seeing. Just the precision of the tone, just the color and the joy of it, but it's also harrowing. Him grabbing the camera. Her eye makeup. It's this combination of whimsical and horrifying and triumphant that just overwhelmed me. It was just the coolest and most upsetting thing that I've ever seen. I think back to all the videos that were trying to shock me. Marilyn Manson, Nine Inch Nails, Tool, “Firestarter,” “Smack My Bitch Up”—none of them came close to the sheer terrified emotional reaction I had to “Goodbye Earl.”

As you dug into the history of an era that you’d lived through, was there anything that you came across that felt surprising or shocking, from a 2023 perspective?

There was a Q Magazine cover—it's Bjork, PJ Harvey, and Tori Amos, and the headline is HIPS, LIPS, TITS, POWER. Those are the gnarliest moments for me. Somebody in one of the other English magazines calling Tori Amos, like, “a turbo-driven fruitcake” or something. Tori says all kinds of kooky things, that’s why she’s so great, but something about the tone of the press. The press around Lilith Fair. Fiona Apple’s press in 1997. The way Tori and Fiona were among the first pop stars to talk about sexual assault, and just to see the word “rape” in a subhead. “Tori Amos talks to us about blank, blank, and rape”-- those are the moments that freak me out the most.

Sinead O'Connor is another example. I read her memoir and it's just the most harrowing book I've ever read in my entire life. To read the immediate reactions to SNL—Joe Pesci saying she'd get slapped, and just the way she was excommunicated. That's in the same vein, in a lighter way, as Fiona saying “This world is bullshit.” The way we treated Left Eye burning Andre Rison’s house down. Bjork’s swan dress. Anything where it was like, Kooky pop star does kooky thing that has no cultural value, but it turns out in retrospect that these were some of the most important and impactful moments of the nineties, and now we owe all of them an apology. We owe Pamela Lee an apology. We owe Lorena Bobbitt an apology. It just goes on and on and on.

There was no episode of the show that I put off for longer and was more afraid of than Britney Spears. I just could not wrap my head around it. The ground was still moving under my feet, and it still is. There was that period where we realized that we owed her this huge, global, years-long apology for everything that we did to her, but then we started apologizing so profusely that we put her in a separate sort of We're apologizing to you cage, and we then over-apologize to her for putting her in it.

As I get older I find myself in a lot of work environments where I’m surrounded by younger people, and it’s always interesting to find out in what respects I am a dyed-in-the-wool ‘90s guy. I remember once having a conversation with a room full of younger co-workers about whether or not to retweet a compliment, and one of the younger people laughing like they couldn’t believe I would even worry about how that would be perceived. But something about it went to the core of my being. I have this aversion to self-promotion and distrust of people who do it, which I feel like is a very ‘90s anxiety that I picked up in part from bands who felt weird about being famous. Right now you’re out on what’s essentially a self-promotional tour. What’s it like for you, as a ‘90s person, to be in that mode?

I guess these conversations don't feel much like self-promotion to me, because this show, and now this book—this is the most reaction I've gotten to anything that I've ever written, ever done by orders of magnitude. I get emails, I get DMs from people, and they like the show and they say very nice things—but what they really want to do is talk about the time they heard Fastball while they were driving to get their teeth cleaned. They want to tell me their own spectacularly mundane—but incredibly important, to them—personal memories, and then we're having a conversation.

I know that part of the reaction that the show has gotten is down to the parasocial nature of podcasts, and that it’s just my voice in people's ears, but I've always loved the level playing field of it—I've always loved the fact that it's not that I'm inherently interesting at all. It's just that I talk about the time I was in a car with people driving to Denny's and “Crash Into Me” came on and everyone went dead silent, and it was just this really holy moment that nobody else outside of that car is ever going to give a shit about.

But you have a similar memory, probably with some far cooler song, and so does everybody else on Earth, and all I'm doing is spurring your own personal memories, and that's what the show does, and that's hopefully what the book does. The promo tour I've been on—I'm just talking to people on podcasts, talking to people at radio stations, and they just want to talk to me about Phish, or about Primus, or about Harvey Danger or whatever, and I just want to listen.

Originally Appeared on GQ