Ripped: My Life as a Competitive Bodybuilder

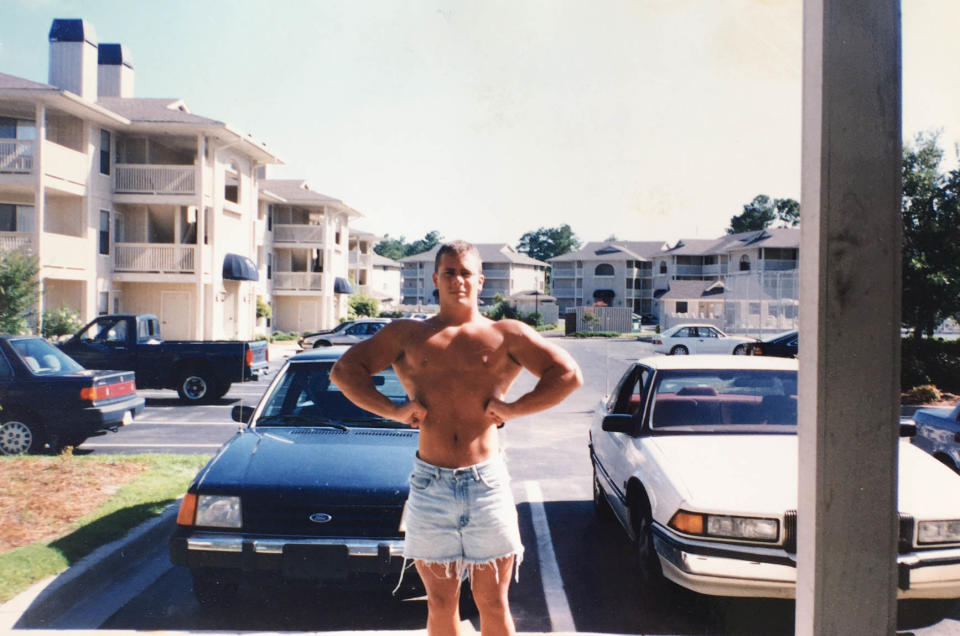

In the deadening heat of an afternoon in 1990, fifteen years old and recently shucked by my first girlfriend for a football star, I wandered over to my uncle Tony's house and found him weightlifting in the pro-grade gym he'd installed in one half of his cobwebbed basement, AC/DC yawping from a set of speakers. The song? "Problem Child." Tony lived across the street from my grandparents, where my father, siblings, and I ate dinner each weeknight, and so I'd known about his gym-he'd built and welded most of it himself-but never had a reason to care about it. Earnestly unjockish, I'd long considered myself the artistic sort. My hero was the reptilian rock god Axl Rose. Filthy and skinny, he looked hepatitic and I thought I should too.

But there in my uncle's basement, my sallow non-physique mocking me from a wall of cracked mirrors, I clutched onto one of the smaller barbells and strained through a round of bicep curls, aping my uncle, who for whatever reason did not laugh or chase me away. And with that barbell in my grip, with blood surging through my slender arms, entire precincts inside me popped to life. Engorged veins pressed against the skin of my tiny biceps, and I rolled up the sleeves of my T-shirt to see them better, to watch their pulsing in the mirror.

Wordlessly I did what my uncle did, trailed him from the barbells to the dumbbells to the pulley machine, trying to keep up, mouthing along to the boisterous lyrics. And in the half hour I spent down there that first day, I had sensations of baptism or birth. Those were thirty minutes during which I'd forgotten to feel even a shard of pity for myself. I didn't know if I was lifting weights the right way, but I knew that I had just been claimed by something holy. I'd return to his basement the following day, and the day after that. I'd return every weekday for two years.

Motherless, I was brought up in a blue-collar New Jersey town by men for whom masculinity was not just a way of being but a sacral creed. My father and uncles and grandfather-we called him "Pop"-admired weightlifters and footballers, wrestlers and boxers, lumberjacks, hunters, woodsmen. Celebrants of risk, they valued muscles, motorcycles, the dignified endurance of pain. Their Homeric standards of manhood divvied men into the heroic or the cowardly, with scant space for gradation. Heroes were immortalized in song, cowards promptly forgotten. This wouldn't have been an issue growing up except that I wasn't like them. I was made of other molecules, of what felt like lesser stuff. As the firstborn son, as the fourth William Giraldi, the pressures were always there, the sense of masculine expectation always acute.

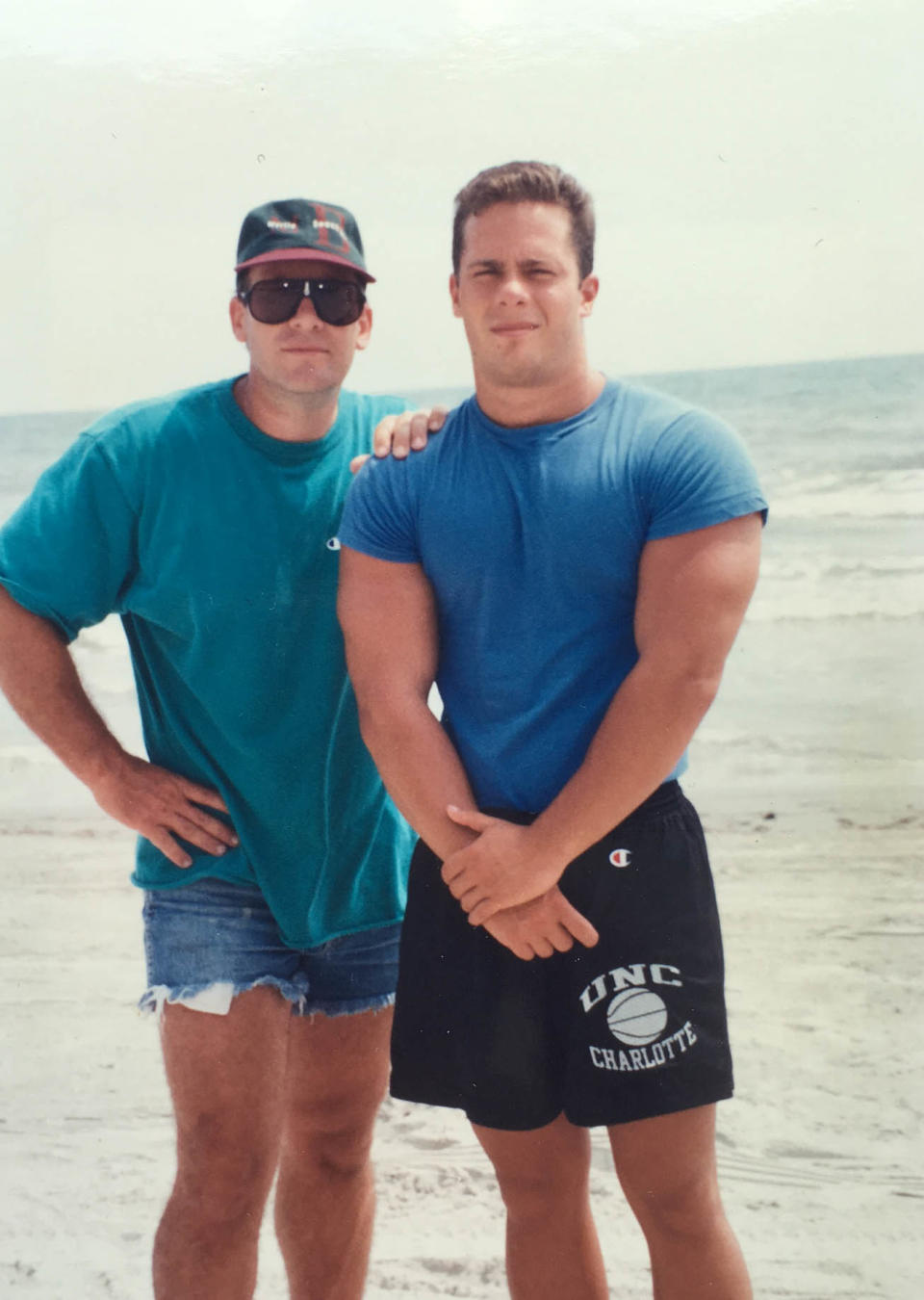

By the time I graduated high school in '92, I had gained full occupancy of the bodybuilding headspace. A coven of boyhood friends had begun training at a gym in the next town called the Physical Edge. I'd known for several months that the dungeoned isolation of my uncle's basement would no longer suffice. Every bodybuilder will eventually require an atmosphere of incitement, a dynamizing gym republic, full membership in the cult.

Set back in a spottily wooded industrial park, behind leaning plots of corn, the Physical Edge was a crimson-and-silver sprawl of modern equipment and Olympic free weights, five thousand square feet of mirror and metal. An aerobics room of chants, an alcove of stationary bikes, treadmills, and StairMasters. Manifold machines of transformation, pulley machines and Smith machines, squat racks, flat and incline and decline benches, a battalion of gray dumbbells, black barbells, red faces pinched and grunting under them. Framed photos of pro bodybuilders in muscular tableau. Everywhere the iron-to-iron slap of plates beneath speakers pealing Soundgarden, Nirvana, Metallica, such distortion-fueled bruit. Everywhere the scent of rubber, oil, and sweat.

On my first day there, I tried to carry myself as if I were accustomed to such onsets of stimuli, but I'm not sure I succeeded at that. You've seen a six-year-old at a summer carnival, his eyes and limbs manic to take in, to test, all things, all at once? It was like that for me. For two years I'd been reading in muscle magazines about gyms such as this-the grotesque men I studied and aspired to join looked like a mash-up of the mechanical and the human-but those articles must have been too puritanical because they forgot to tell me about the humming sexuality, the pre-orgasmic splendor of the place, those about-to-give-birth attitudes.

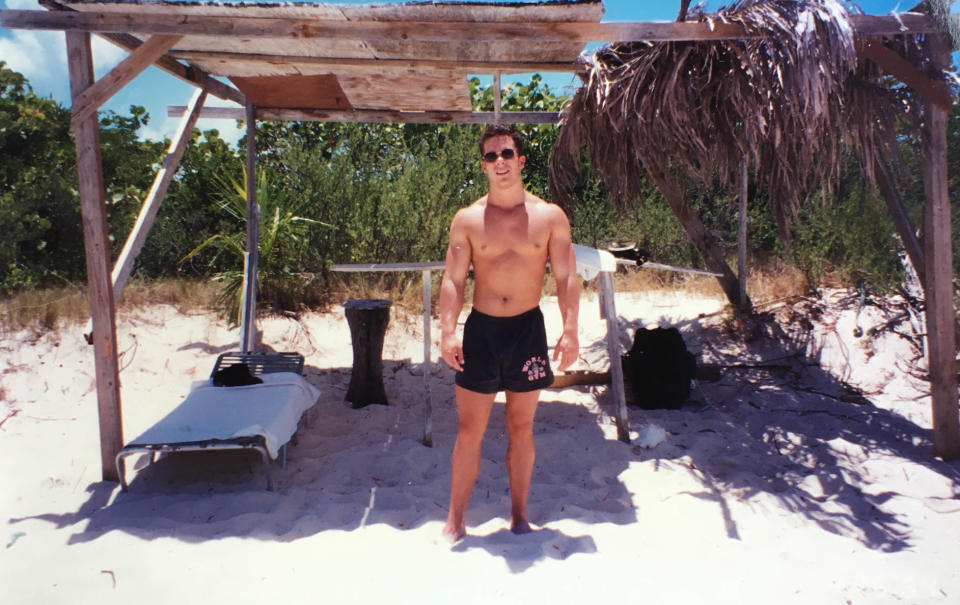

It wasn't long before I was adopted by the grandees of the Physical Edge, enormously muscled men who saw in my body stage potential, the necessary symmetry and fluidity of physique to be a competitive bodybuilder. My training partner, Victor, had competed before, and a pair of guys we called Rude, after the pro wrestler Rick Rude, and Sid, after the pro wrestler Sid Vicious, knew more about diet and training than anyone else at the Edge. These three chaperoned me into the cosmos of competitive bodybuilding, an underground of truly hell-bent individuals.

The bodybuilding stage, with its strictness of rules, its rigidity of judgment and ferocity of competition, its stress and its heat, destroys any possibility of eroticism.

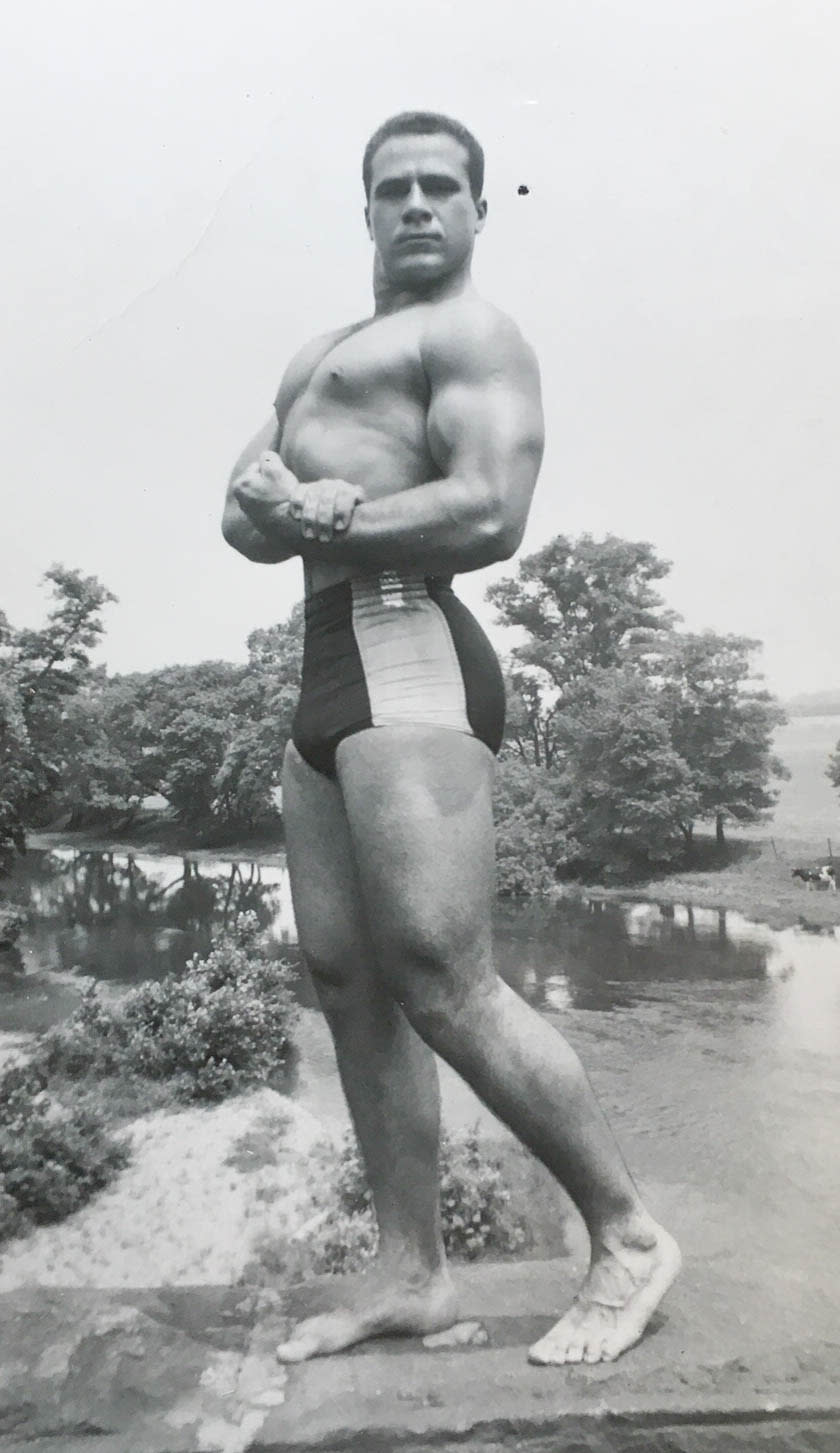

For working-class kids who came of age in the bigness and bluster of the Reagan '80s, who were soused on the action flicks of Schwarzenegger and Stallone, on the bombast of Hulk Hogan, muscled physiques were simply what you pined for. What happened to me in the early '90s was part of a grander cultural trend that had jumped to life a decade earlier when the American political mood took a hard right turn. Cartoonish musclemen, typified by Schwarzenegger and Stallone, arrived to supplant the "girlie-men" of the '70s, to redeem us from the humiliating failures of Vietnam and the emasculating victories of feminism. If we wanted to win wars, actual and cultural and personal, we needed all the muscle we could get. In Rambo: First Blood Part II, when Rambo's former colonel springs him from prison so that the great warrior can return to Vietnam in search of POWs, Rambo asks, "Do we get to win this time?"

Unlike the UFC, which in recent years has burst into the mainstream, bodybuilding remains a cult sport, in part because its status as a sport is not entirely accepted: it looks and feels more like spectacle than sport, more performance art than athletics. The following, adapted from my memoir The Hero's Body, is an account of my first bodybuilding show, when I was nineteen years old, in Point Pleasant, New Jersey.-WILLIAM GIRALDI

The morning of the show, the prejudging portion, a muster of attendees mistaking gaudiness for godliness, not an overweight ice-cream lover among them, skin enough for a porn convention, outfits with an emphasis on both the "out" and the "fit." The air inside the auditorium was charged and hard to breathe, crammed with bovine strut, men grazing from containers, ripping protein bars with their teeth.

Victor stood with me in the queue near the face of the stage so I could sign in, receive my number badge, and hand over the CD with my posing song for later that night. We tried to spot the other teens, to gauge my competition, but they all looked the same: sandals, thigh-flared workout pants, hoodies zipped to the throat, duffel bags like pocketbooks beneath their arms.

Backstage, Victor sprayed another sheath of bronzer on me, then added an enamel of posing oil, its odor like the flavored lubricant in your bedroom. The noxious fumes of the body paint were a smog in that tight air, every man backstage laminated with the stuff, his face scrunched, trying not to inhale it. We stood or sat in our posing trunks before mirrors, eighty mostly-nudes from all weight divisions, pumping up with dumbbells and barbells, some lying on the floor with their legs up on benches to reduce water retention in their legs, eyeballs spookily aglow against newly coppered hides, nobody speaking, each sizing up the other, everybody emotionally withered from the diet.

A paramedic stood sentry in a starched white button-up in case someone passed out, his stethoscope round his neck and ready to sound our unhinged hearts. I nudged Victor in unease, nodded to the teens who dwarfed me, the full lobes of their pectorals. Two teens in particular were blessed with size and superior scaffolding, both humped with muscle; their ears looked muscled. I'm sure I'd never duped myself into believing that I had those same genetic gifts, and yet there I was, having been talked into this, an impostor backstage with these teen freaks who would trounce me.

Victor whispered, "You're shredded, bro. That dude's not peeled like you," and "You're nails, man, got veins everywhere," and "Don't sweat them dudes. You're nails."

But it was impossible not to sweat because I was wearing nine layers of epidermis in a Sahara of body heat. There were eight guys in the teenage division and I was sure-it was a stomach-pit surety-that I was better than only two of them.

So: sixth place for me, it seemed. You don't get a trophy for sixth place, and you make no one proud.

Soon the teens were summoned to center stage, lined up by number, elbow-to-elbow, our backs flared, legs and abs tensed, behind us a silver-spangled curtain on loan from a strip show. The announcer called the first move, four quarter-turns to the right, and then he called out the mandatory poses, one by one, beginning with Front Double Biceps. We held each pose for twelve, thirteen seconds, and although that's not long to clench your breath, the body feels it as much longer because the flexing forces an onrush of blood, the dilation of veins, each muscle group leaping distinct and hard. What's more, you've got to be aware of the other guys because the wily ones will try to inch forward on the stage in an attempt to stand out.

I was pinned there between the two largest teens, crushingly aware of how little I must look, merely planar by contrast. I could hear Rude and Sid shouting at me, though not Victor (Victor didn't shout). I heard "Abs!" and "Calves!"-reminders to flex them, to pose from the floor up: calves first, then legs, then abs, then the upper body. During the rear poses, Rude shouted, "Hams!" because apparently I was forgetting about my hamstrings, which were rather easy to forget about because I didn't have any. Sid yelled, "Glutes!" and I squeezed my buttocks into striated squares.

We'd practiced each pose for several weeks and yet, when you're a first-timer, an unfortunate thing can happen up there. In the heat of it, all the posing prep falls aside and you begin simply trying to keep pace with those beside you, following whatever they do, because surely they have more experience than your sorry self. Pose by pose-Side Chest, Back Lat Spread, Back Double Biceps, and the rest-I simply tried to keep up with the leviathans who flanked me, looking side to side to see their poses, their stances, whatever in the world their faces were doing.

The head judge then scattered the lineup, microphoned where he wanted us to stand: "Number 22, next to number 19. Number 20 in between Numbers 21 and 18." This meant they were comparing the best physiques more scrupulously. I knew it was an ominous sign to be on either end of the line because that meant they didn't care to compare you, and not, alas, because you were incomparable. You wanted to be at the center of the lineup; that's usually where the top placers appear at this point. Although I wasn't at the center, I also hadn't been exiled to either end. So, the slightest fattening of hope, then, among such pounding doubt. And once again the judges bullwhipped us through the eight compulsory poses.

A paramedic stood sentry in a starched white button-up in case someone passed out, his stethoscope round his neck and ready to sound our unhinged hearts.

Those who contend that bodybuilding isn't a sport because it lacks utility, a specific function of physicality, have never attempted rounds of competitive poses in lanes of scorching spotlight. The skill lies first in the difficult mastering of muscle development and nutrition, in the wedding of power with grace-grace is the body thinking clearly-and then in this racking exposition of the outcome. Hitting and holding those poses in such heat, with a body that dehydrated, with the elbows, shoulders, and thighs of others nudging greasily into me, was as difficult, as technical, as building the muscles in the first place.

I can half understand the cynic's charges of homophilia: those male bodies, ninety-eight percent nude, grunting and sweating, slick together. But it doesn't come remotely close to feeling that way. It feels like combat, not prelude to coitus. The bodybuilding stage, with its strictness of rules, its rigidity of judgment and ferocity of competition, its stress and its heat, destroys any possibility of eroticism. The art/sport display, the objectifying of the body into pure aesthetics, into lines and form and flow, empties it of all sexuality. You actually forget you're naked. That's why no bodybuilder ever worries about sprouting an erection on stage; there's simply no space up there for an erogenous zone.

After that second round of compulsory poses, the judges dismissed us, thanked us, and I walked off stage cramping in my quads. Victor was there in the wings with a towel and he patted the sweat from me. The head of a Poland Spring bottle peeked from the side pocket of his shorts like a periscope, and when I grabbed for it, he swatted my hand away. I wasn't allowed any water-water would ruin the muscle striations I'd obtained after six weeks of dieting. He unscrewed the cap and carefully filled it with barely two milliliters of water, which evaporated on my tongue before I could swallow.

It was impossible not to sweat because I was wearing nine layers of epidermis in a Sahara of body heat.

He and the others from the Edge would remain to watch the prejudging of the other weight classes, but they instructed me to return to the hotel.

"Go lay down, stay off your feet."

"Put your legs up on pillows to keep the water out of 'em."

"For the love of God, whatever you do, don't drink any water."

"Find a hamburger and eat it. You looked a little flat up there. You need to fill out. A hamburger will fill you out."

"Sips maybe to get the burger down."

"Sips, fucker, no more than sips."

"But overall, great, man. You held your own up there."

"You looked killer, dude."

"You looked great."

"You looked good. It ain't over. Tonight still matters. At this point, the judges are eighty percent sure of the placements, I'd say, so tonight still matters. You can't screw up anything between now and then."

"Yeah, you looked a little flat, as I'm saying. So go get a hamburger. Get two. No water."

That might sound counterintuitive, a mooing hamburger and bun, but my body fat percentage was so low at this point, my metabolism so high, and my anabolic rate so efficient after many weeks of training and diet, that the burger's density of fat and carbs would get stuffed directly into my muscle bellies, keeping them round and causing my veins to surge. A hamburger for the average American is a cardiac catastrophe in the making; a hamburger for a bodybuilder on contest day is a necessary nectar.

I found a plaque-friendly grill on the way from the auditorium-you could smell the cholesterol a block away-and bought the hamburgers. Trying to eat them in my motel room without any water took an hour. After jerking shut the blinds I dialed my house and then my grandparents', but no one answered at either place. Without traffic, Point Pleasant was an hour south of my hometown, and I wanted to remind my family to leave early enough; the show began at seven.

On the bed, on a sheet already dyed with streaks of bronzer, needing to sleep and feeling myself fill from the burgers, I lay half in dream, half in fearful remembrance, and what I dream-remembered was this:

Six months earlier, Victor and I and some others from the Edge attended the prejudging portion of a minor bodybuilding contest held at a high school auditorium in north Jersey. One of the competitors was mentally disabled, maybe twenty years old; you could see the slight warp, the frozen twitch, in his face. He wasn't just unmuscled-he looked shriveled from malnutrition, earnestly straining and oblivious. He'd applied a layer of oil and shaved his body, but nobody had told him about self-tanner, and so he glowed ghoulishly on stage next to dark copper hides, all of them many times more massive. The universal nightmare in which you're naked in front of a crowd of people mocking you? This blanched stick figure was that nightmare incarnate, except he didn't know it.

Those who contend that bodybuilding isn't a sport because it lacks utility, a specific function of physicality, have never attempted rounds of competitive poses in lanes of scorching spotlight.

Somehow this had been allowed to happen, but no one seemed to know what to do about it now. The judges and other competitors were paused in perplexity and embarrassment, and then determined to move forward, and then paused again. The head judge's voice in the microphone quavered with umms and errs. He looked left and right for help from the other judges, but no help came. The fifty or so spectators reddened, quaked with quiet laughter, and I could hear the cruel whispers around me: Who let a retard onstage?

The guys from the Edge slid low in their seats, their baseball caps yanked down over their brows, literally crying from the unexpected comedy of this. I was afraid my own tears would come then, and that they wouldn't be from laughter. That release of emotion would have been the end of me at the Edge. Because I could see, there in the front row, a blocky silver-haired man in mismatched garb, his eyeglasses built for star-gazing, something warped in his face too, pitched eagerly forward in his seat, ignoring the ridicule, beaming encouragement and faith up to the ghoulish kid who'd been wrongly placed on that stage-beaming at his son.

Backstage at the night show, after Victor varnished me with a final layer of posing oil, I could hear the auditorium filling, the balanced pre-performance din. I asked Victor to check if he could spot my family in their seats, but he couldn't make out anyone. Hundreds of spectating faces somehow coalesce into a single face. I'd heard someone say that the traffic on the Garden State Parkway was clogged for miles into Point Pleasant. Early August was the crest of beach season, carloads in swarm for a Saturday night's play. I guessed that my family was idling in that clog. The teens would be first to compete, and so I was certain that my father, Pop, and Tony would miss me onstage.

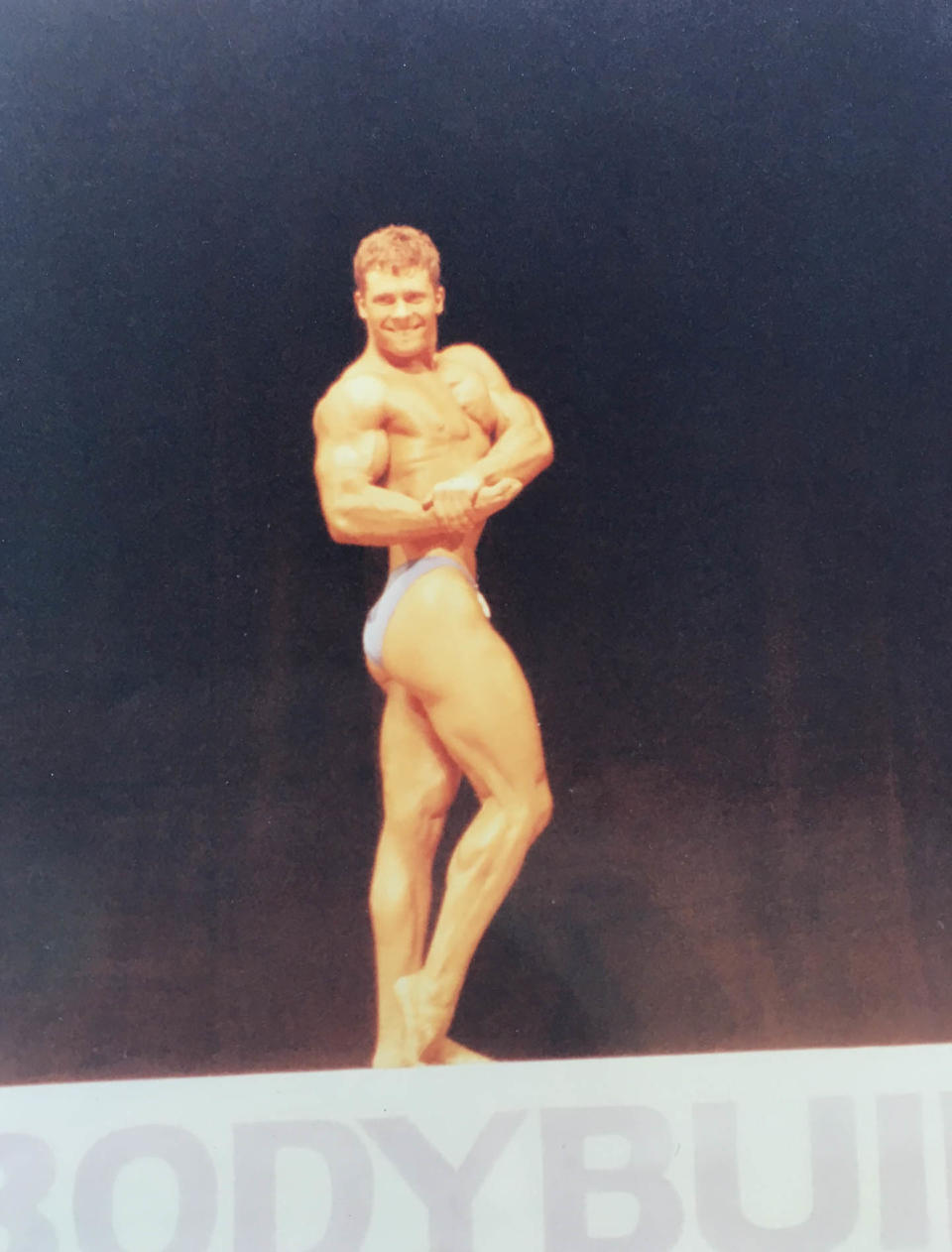

It all unfolded quickly then, in the way events do after so much buildup. The teen division was instructed to form a queue at the curtain, and each guy would perform his solo routine before we were called onstage for another posing competition. When it was my turn, the announcer sang my number and name in the drawn-out, faux-dramatic manner of every boxing announcer you've ever heard.

I walked in to the clapping, the orchestra of whistles and hoots from the Edge crowd. The way the lights were angled, I couldn't see farther than the judges' table and the first two rows. The rest was a bleary canvas of beiges and blacks. But my body could feel the noise of them all, their mass humming along my bones. Flashbulbs were going off to my right like a squadron of fireflies who knew my name. When the song began, I performed my routine-a banana-sack ballet, as I'd come to think of it-just as we'd rehearsed it for the last several weeks.

Or at least I tried to. It felt hectic up there, and I was conscious of missing certain beats, of being either a second too quick or too slow to hit a pose. I thought I could hear Sid or Rude shouting, "Time!" over my song, by which he meant Keep in time with themusic. The guys who'd gone before me looked somewhat clumsy in their choreography, and so I strained for agility, for elegance, aware that elegance can't be had by straining.

And just as I was starting to relax, to feel semi-assured in the routine, to remember all my beats, the volume descended and the song disappeared. I'd seen guys bow at this point, or else kiss their hands toward the audience in appreciation, but I swiped my wet brow and waved goodbye, squinting into the lights as I tried to spot my family.

I stood by in the wing, stage left, while the others performed, baby-sipping from a water bottle, hopped-up now, feeling a muscle tautness just shy of cramping, Victor behind me with a towel, blending my sweat into the oil, saying, "Killer job, you nailed it," but I didn't believe that. Gawking at the obsidian beauty who was just then performing to a hip-hop blend of Naughty by Nature and the Wu Tang Clan, I couldn't believe that. After the last guy's routine, we were all summoned to center stage to go through the mandatory poses. I was near the heart of the lineup again, dwarfed again, and if the guys from the Edge were yelling reminders at me, I couldn't hear them over the crowd.

Then came the posedown, an unscripted minute of free-for-all posing to whatever guitars burst through the speakers, all eight guys elbowing for a spot at the lip of center stage, the sweat and oil stink of us, trying to smile, some of us virtually hugging, trying to get around one another. The music stopped at sixty seconds, but guys were still hitting shots for the judges, and everybody had to be ordered back into line. This posedown was for the audience; it didn't matter for winning or losing because the judges had already finalized their decisions during the posing competition.

I strained for agility, for elegance, aware that elegance can't be had by straining.

Now we statues stood at the line, waiting to hear the top five numbers. When your number was yelled, you stepped forward. If your number wasn't yelled, you didn't place, and you remained lonesomely at the line. The top five would stand on the dais, but only the top three would be handed trophies-two-foot, two-tiered oak and silver-sprayed sculptures of a muscled demigod in mid-pose, forty pounds apiece, expertly crafted. My number was among the five. And so I'd be fifth place, I thought: fifth among eight. But when the announcer yelled the number for fifth place, it was not mine. Nor was fourth.

At this point, something begins to happen to the enlivened competitor, the formerly insecure one who an hour earlier thought he'd take sixth place. He begins to think not about the possibility of third place or second place, but about the possibility of first place. It's an optimistic delusion based upon the suddenly fortuitous, a reversal of fortune. My brief rationale was this: I thought I'd be in sixth place, but now I'm in the top three, and if I can be third, then I can be first, because the distance between third and first is much narrower than the distance between sixth and first. Well, of course it is, but that didn't mean that there was no distance between third and first, and to remind myself of this, to dispel the delusion, all I had to do was glance at the other two guys who remained in the lineup with me.

For working-class kids who were soused on the action flicks of Schwarzenegger and Stallone, on the bombast of Hulk Hogan, muscled physiques were simply what you pined for.

Third place was announced and it wasn't my number, and I began to suspect that major errors were being committed. I twisted the badge on my trunks to check it, to make sure I was seeing and hearing numbers correctly, because the kid to whom they'd just given third place outmuscled me by about twenty-five pounds. Only I and the obsidian beauty now, the toothpick and the sirloin, and when they gave me second place it felt like relief. Not relief that this madness was finally finished and I could down a canter of water and a chocolate bar, although that too, but relief that rightness had prevailed. The world now and then peddles justice.

It didn't feel anything like justice to the third placer. I wasn't aware of this at the time, but in photographs from that night, we three perched and posing on the dais with our trophies, I can see his indignant smirk, his awareness that he'd just been robbed of second place. And robbed he surely was, although why, I don't know; perhaps because the judges didn't like his attitude (he'd been pushy, arrogant during posing), perhaps because his skin was denser than mine, his routine less graceful.

I walked behind the curtain with forty pounds of trophy, through the backstage flurry to dress myself, to receive high-fives from Victor, congrats and shoulder pats from giants all around. In the silent, fluorescent hallway that led to my seat in the auditorium, I bent into the water fountain to gulp for an uninterrupted two minutes. But what flooded me then was a mix of pride and bliss, a mix I'd never felt before, and one I'd have to wait sixteen years to feel again, when my first son was born.

My father, Pop, and Tony were there in seats at the rear of the auditorium, and when I entered they rose to greet me, each grinning, nodding, and I hoisted the trophy to chest level as if to say, "Ta da."

"That's one hell of a trophy," Pop said. "I didn't think you'd make better than fifth place."

"You did good," my father said. "I had you at third place."

"I had you at second," Tony said. "You were better than that third place kid. He was big but he had no shape."

Before we took our seats, my father, with a calculated slyness, handed me a small paper bag, as if he didn't want anyone else in the auditorium to see it: an assortment of Snickers and Reese's Peanut Butter Cups. He said, "I thought you might be craving one of those."

I said, "How'd you know?"

He said, "I know things," and together we finished off that bag of chocolate.