Richard Avedon’s Work to Be Focus of Gagosian Show

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“How many photographers is Richard Avedon?”

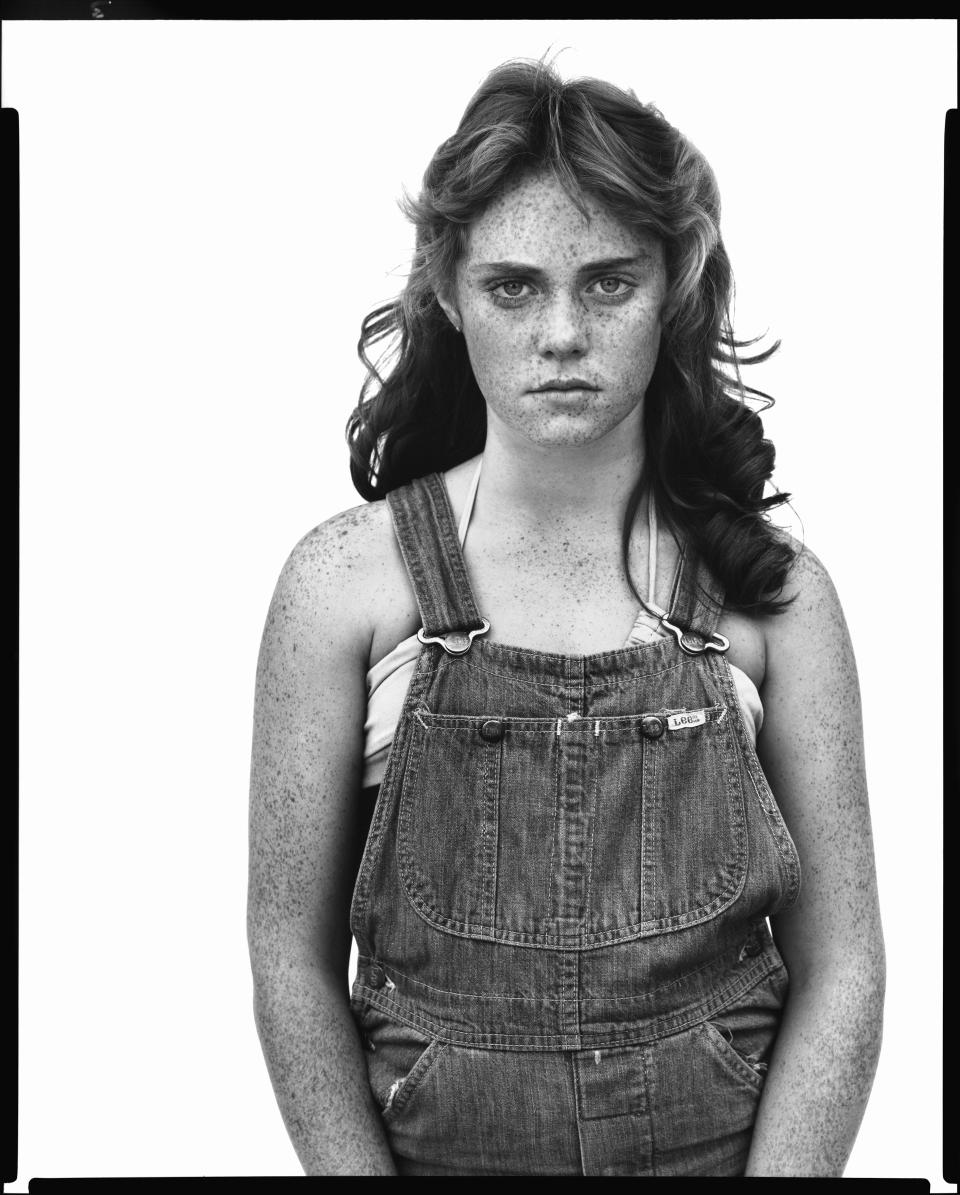

That was the conundrum for the executive director of the lensman’s foundation James Martin in laying the groundwork for “Avedon 100,” an exhibition that will bow at one of Gagosian’s Chelsea galleries in Manhattan in May. “Avedon was so prolific in his career that a lot of people have segmented ideas about his work, [thinking], ‘Oh, he’s a fashion photographer’ or ‘He takes these severe portraits’ or ‘This is his documentation of working people in the West,’” Martin said.

More from WWD

It’s easy to see how Martin, who first worked as an assistant, archivist, cameraman, printer and liason to Avedon in 2002 and joined the foundation at the request of the photographer’s family following his death in 2004, is inclined to speak of the legendary photographer in the present tense. Never mind Avedon’s ongoing influence on photography today.

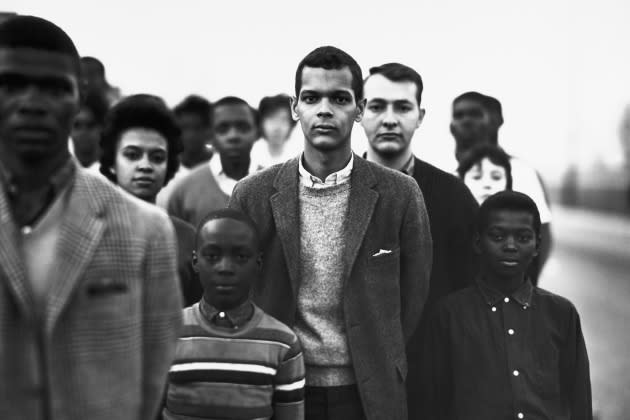

Organized to mark the centenary of Avedon’s birth, the exhibition will feature images from his “In the American West” series, social justice movement, as well as classic portraiture, advertising and fashion work. Nearly 150 cross-disciplinary talents have been tapped to select an Avedon photograph and highlight its impact on them. Naomi Campbell, Elton John, Spike Lee, Sally Mann, Polly Mellen, Kate Moss, Christy Turlington, Chloë Sevigny, Taryn Simon, Jonas Wood and Hilton Als are among the creatives that have agreed.

The range of talents is in synch with Avedon’s interest in the arts and “opening conversations with people in the cultural consciousness. He talked to writers all the time. Many of his friends were playwrights. All of that, I’m sure, influenced him and [affected] his understanding of his legacy,” Martin said.

The lensman’s 1962 photo essay featuring model Suzy Parker and then-comedian Mike Nichols being hunted down by the paparazzi is one example of Avedon’s influence on photography today. The set-up was a spoof of the real-life chase that happened to Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton through the streets of Rome, which was a relative new phenomenon at that time, Martin said. “It’s so funny how many echoes of Dick’s work are reflected in contemporary photography….You see these photo narratives that incorporate fashion into the surroundings in work that you see today.“

Early in his career, Avedon had the wherewithal to take models outdoors in Paris and away from the confines of a four-walled photo studio, preferring to showcase a Balenciaga-clad woman seated at a café with her dogs. That early idea of taking fashion out into the world also provided social context. Late in 1946, Avedon arrived in Paris to cover the reopening French couture houses, which had been closed during World War II.

“Paris then did not have the glamour that it did in its pre-war days. He was bringing these models out there to show that Paris was alive again. Fashion was alive again,” Martin said, adding that Avedon’s influence can still be seen in any fashion magazine.

Conversely with portraiture, Avedon laid bare the essence of whomever was before him by using an all-white background “to depict who this person is staring directly into the lens of the camera,” he said.

Movie fans may already know that Avedon was the inspiration for the fashion photographer in the 1957 musical comedy “Funny Face,” which was loosely based on how he met his first wife Doe. As the film’s visual adviser, Avedon would be on set to help Fred Astaire, who played fictitious fashion photographer Dick Avery, strike just the right pose as he photographed his costar, Audrey Hepburn. More proven industry stalwarts like Diana Vreeland and Alexey Brodovitch inspired other characters.

Legacy was very much a priority for Avedon, who “had his hand in every exhibition that he made and complete control over every production of his work that would be seen by a wider audience,” Martin said. In addition, his will mandated that there would be no posthumous printing of his work. Had Avedon been around for his 100th birthday, he would be reprinting everything and making all of the selections, he said, citing “exquisitely printed” silver gelatin prints from the photographer’s 1978 [largely] fashion exhibition [‘Avedon: Photographs 1947 – 1977’] at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Martin often sat with Avedon in his archives — which include about 500,000 negatives representing about 15,000 jobs that Avedon took on during his extensive career — looking at contacts and negatives from sittings. His practice of always having a second image — or sometimes a few more — to use for himself can be seen in the marked-up contact sheets, Martin said. Often the images that appeared in fashion magazines and other publications were not the ones that Avedon would print. Once selections were made, Martin would cut them out and shred the remaining material to ensure that future generations would not view all of the negatives as all of Avedon’s choices.

Furthermore, the photographer kept two logbooks — one detailing sittings with the names of the subject, hairstylist, the location and minimal other information and a second identical journal highlighting his appointments with such specifics as any animals that had been involved as well as participating agencies. During his lifetime, Avedon had Martin and others create databases with all of that intel, enabling them to track nearly hour-by-hour moments in his entire career, save for some missing holes in the early part of his career.

“From 1954 to 2004, we have a very firm idea of what he’s working on, who he’s photographing and that all was an eye toward building a legacy,” he said. “When the foundation started, we weren’t using any loose paper trying to recreate what Avedon is.”

Running through June 24, the exhibition will be on view at Gagosian’s location at 522 West 21st Street in New York and it being designed by architect David Adjaye. Just as Avedon was known to breeze through exhibitions of his work from time to time to eavesdrop on what visitors drew from it.

“He was really interested in how audiences received his images. Every artist works in a bit of a bubble. They don’t know what it is until it is released out there, and you hear people having real conversations. There is really joy in finding people have interest in areas, where you might not necessarily have those same interests,” Martin said.

To that point, casting out a wide net to all kinds of people — curators, artists, fashion models, musicians and other tastemakers — to participate in “Avedon 100” is a reflection of that eavesdropping. “Why are any of these people interested in any of this work?” Martin mused.

Extending that sensibility, a companion book will give readers a chance to eavesdrop on those conversations, he added. (The illustrated catalogue features an essay from Harvard University associate professor and Vision & Justice founder Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, as well as one from Derek Blasberg.)

“If you are looking at it for Dick’s intention, maybe go back to 2002, where you’re standing with him as he is eavesdropping on conversations that are happening [at The Met’s 2002 exhibition “Richard Avedon: Portraits”]. That’s what you’re going to get at this centennial exhibition in 2023.”