Reykjavík in Wintertime Is a Dream Destination for Book Lovers — Here’s Why

Each holiday season, there’s only one thing on Icelanders’ wish lists: a stack of new books.

Axel Sigurðarson

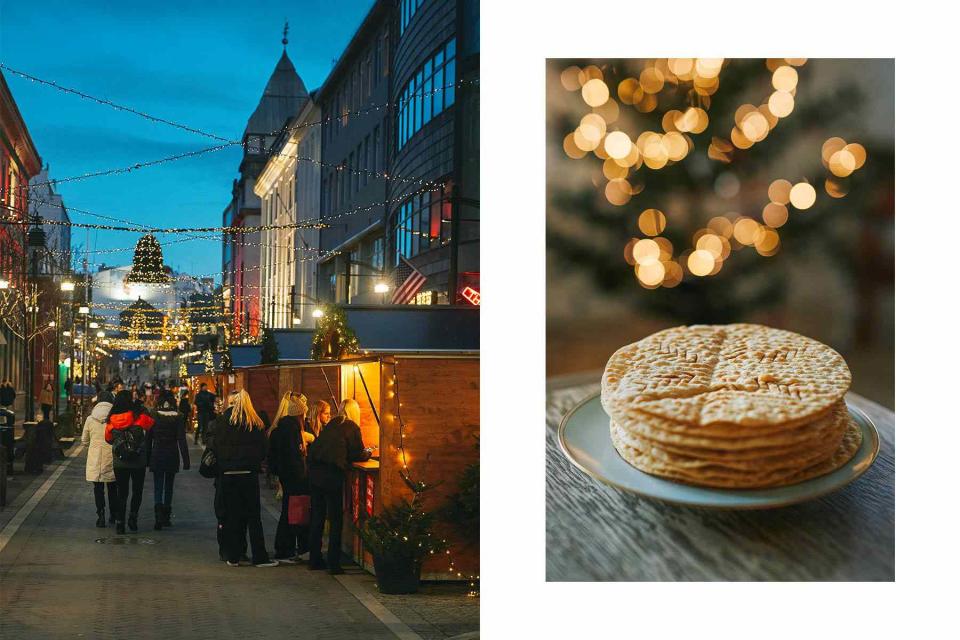

From left: A Christmas market on Austurstræti; Laufabrauð, or leaf bread, is a typical Icelandic holiday treat.In Iceland's Heiðmörk Nature Reserve, just outside Reykjavík, I sat in front of a small fire and waited for the reading to begin. It was raining steadily, but Icelanders do not cancel for bad weather. After a small crowd had gathered, Sunna Dís Másdóttir read an excerpt from "Olía," a book she co-authored with five members of her writing group, who call themselves the Svikaskáld, or “Impostor Poets.” “Each of us wrote one character’s voice,” Másdóttir told me later, “and we wrote intensely in a cabin, away from distractions.”

Literature is central to Iceland’s identity — the storytelling tradition stretches back at least as far as the sagas that were recorded in the 13th century. These novel-like accounts, which describe the conflicts between the Norse and Celtic families who lived on the island from the ninth to 11th centuries, have inspired several modern works, including The Lord of the Rings. Today, one in 10 Icelanders will become a published writer, and 1,500 new books are typically released each year. Since 2011, Reykjavík has been designated a UNESCO City of Literature, for both its long literary history and its contemporary writing festivals and conferences.

Each year, the country’s love of the written word culminates in Jólabókaflóðið, or “Christmas Book Flood,” a tradition that first emerged during World War II. Wartime restrictions were more lenient on paper than on other goods, so giving books as gifts became popular. To help Icelanders make their selections, every November the Icelandic Publishing Association sends a catalogue with the past year’s new titles, called the Bókatíðindi (“book bulletin”), to each home. On Christmas Eve, loved ones exchange the books they ordered and then read late into the night.

Axel Sigurðarson

Sunna Dís Másdóttir reads from a book she co-authored with a group of other IcelandersWhen I visited Reykjavík before Christmas last year, I found author readings at pop-up markets and at long-standing institutions like Bókakjallarinn, a rare and antiquarian bookshop that houses a printing press in the basement. One day, I walked to Ingólfur Square and found a temporary ice rink — where a dozen children in puffy snowsuits skated in circles — surrounded by wooden stalls. Vendors sold wool clothing, hangikjöt (smoked lamb), honeyed almonds, and laufabrauð, a thin, circular flatbread decorated with snowflake cutouts. From one of the stalls, I purchased a to-go cup of jólaglögg, an Icelandic version of mulled wine, spiked with vodka and flavored with cardamom and cinnamon.

Sipping my jólaglögg, I walked along Austurstræti and popped into a Penninn Eymundsson, a national chain of bookstores (the oldest was established in 1872). Eager to see if a friend’s book was available and translated into Icelandic, I was disappointed to find it was sold out — but happy for my friend. I did, however, find several children’s books about the seasonal myth of the Yule Lads and their cat, Jólakötturinn, often known as Jóla.

The myth has softened over the years, but legend has it that Jóla will eat any child who does not receive a piece of new clothing on the holiday. The Yule Lads — 13 mischievous Santa Claus–like figures who, in the original telling, were more like trolls who terrorized children — come down from their mountain home one by one for the 13 nights before Christmas, leaving treats in young ones’ shoes. The ill-behaved, however, may find rotten potatoes waiting for them the next morning.

Axel Sigurðarson

Winter light on Tjörnin, a lake in downtown Reykjavík.In Iceland, Christmas Eve is reserved for unwrapping gifts and singing songs around the tree after a traditional meal of wild grouse or smoked leg of lamb. Christmas Day is a day of rest. It’s also when, the story goes, the first of the Yule Lads departs for his mountain home, to be followed by each of his brothers over the next 13 days until Epiphany on Jan. 6. That’s when Icelanders will gather around bonfires and bid farewell to all of the Yule celebrations until next year. Still, for many, the books received over the holiday will remain a source of comfort during the dark winter months ahead.

A version of this story first appeared in the November 2022 issue of Travel + Leisure under the headline "A Christmas Story."

For more Travel & Leisure news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Travel & Leisure.