How to Rewrite Royal History

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

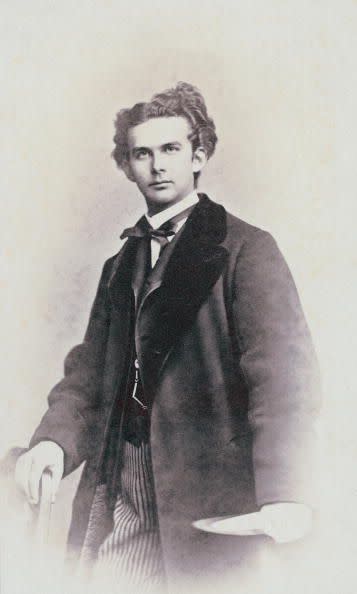

Any student of fairy tales can tell you that the origins of these well-worn stories are almost always darker than we’ve been led to believe. The same applies to the lives of Ludwig II and Empress Elisabeth, two 19th-century monarchs who helped shape our conception of what fairytale royalty should be. Ludwig’s spun-sugar German castle, Neuschwanstein, is credited as one of the inspirations for Cinderella’s Castle at Disney World, while depictions of Elisabeth’s bucolic childhood in films like Sissi fall somewhere between Snow White and Bambi. In fact, there were no happy endings: the two cousins and friends led lives of immense privilege and beauty that were also marked by betrayal, madness, and murder.

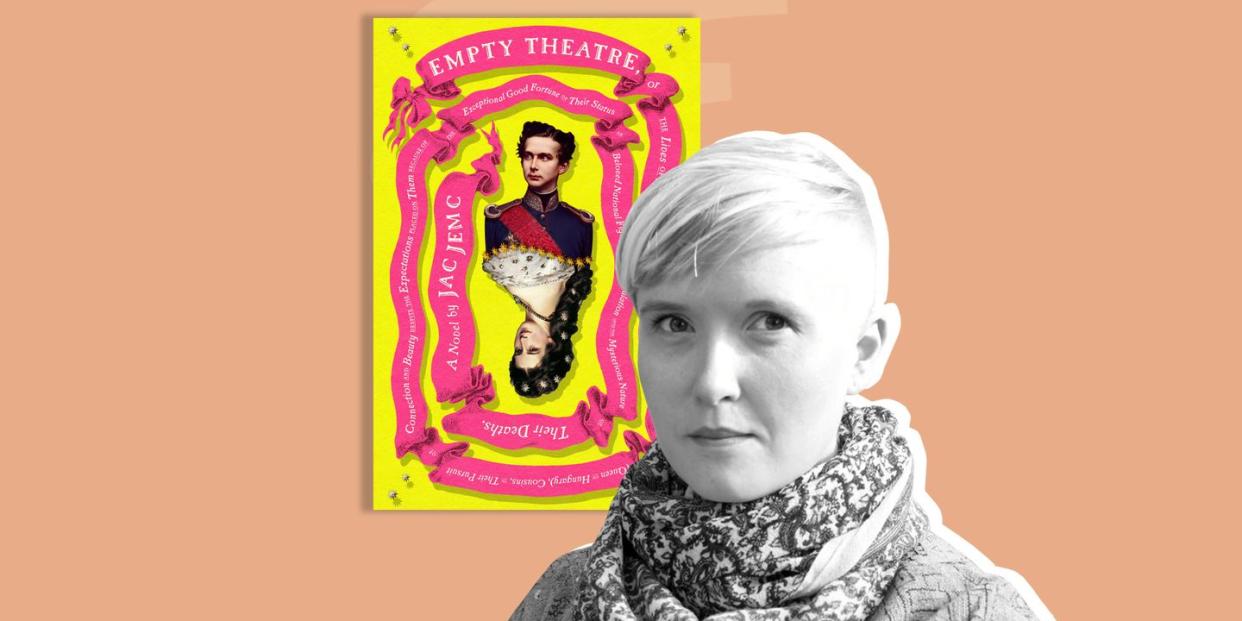

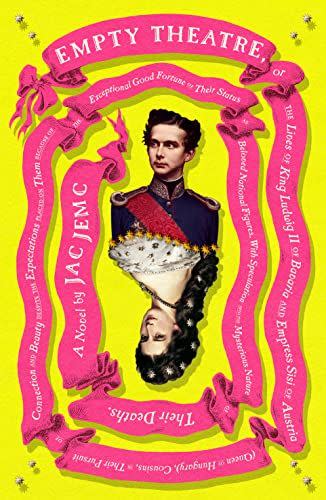

Jac Jemc’s latest novel, Empty Theatre, follows Ludwig and Elisabeth (also called Sisi) from their Bavarian childhoods to their ascension to their respective thrones (Ludwig as King of Bavaria, Elisabeth as Empress of Austria and Hungary), through the often painful years that followed, all the way to their deaths. The book’s scope is vast: readers are privy to the machinations that help to consolidate Austria and Hungary, as well as the North German Confederation, setting the stage for the wars of the following century. Great artists also make up the cast: Ludwig was in close contact with composer Richard Wagner, whom he called his “Great Friend,” and sculptress Elisabeth Ney and painter Franz Winterhalter also make appearances.

But more than any moment of world historical or artistic import, what will grip readers in Empty Theatre are the intimate, human moments that color the lives of these monarchs. Ludwig wrestles with his sexuality (particularly his longstanding attachment to stable master Richard Hornig) and shirks his responsibilities as a ruler to commission costly castles and operas. Elisabeth, straining against the restrictions imposed on her gender, struggles for the authority to raise her own children, to help unify her dual nations, and to maintain her fabled beauty, eventually seeking escape further and further from the stultifying Hapsburg court. Readers may be familiar with some of this history following Elisabeth’s recent on-screen breakout (her life was dramatized in the historical drama Corsage and the Netflix series The Empress). Reclusive and melancholic, both cousins also live under the threat of their own blood, being descended from the ancient (and heavily braided) Wittelsbach dynasty, one prone to mental illness.

Empty Theatre neatly avoids the temptation to dwell on the pathos of these stories. Jemc’s arch, anachronistic narrator moves swiftly between its two subjects, parsing out moments of joyful abandon and unhinged absurdity to counterbalance all the tragedy. The result is a book that offers much more than history—it recounts the lives of two one-in-a-lifetime characters, and leaves readers with a sense of possibility more than finality. To mark the release of Jemc’s latest novel, Esquire sat down with the author to talk about Ludwig and Elisabeth’s queer credentials, the stranger-than-fiction absurdities of their lives, and the small mercies of an alternative ending.

ESQUIRE: Let’s start with the basics. How did you land on these two characters? What drew you to them?

JAC JEMC: I first dove into Ludwig on vacation, visiting Neuschwanstein. When I saw that big, sugary castle and heard the story of his mysterious death I was sold. So I started learning as much as I could, and I realized that there were all these incredible, compelling women that were peripheral in his life. I wonder what it would be like to try to write a novel about him and them. There were other characters beyond just Ludwig and Sisi as main narrative threads initially, but it ended up getting boiled down to the two of them when I figured out what the book was actually about.

Which characters were reduced?

There was a long Lola Montez storyline. She’s the “Spanish” dancer (actually an Irish lady) who conned Ludwig II’s grandfather, Ludwig I, into stepping down from the throne by seducing him. The other main thread was the sculptress Elisabeth Ney, who Bismarck talked into sculpting Ludwig II and trying to bend his ear toward the side of the North German Confederation and Prussia. Both of those narratives end up with the characters moving to America to try and find some of the freedom that they felt they weren’t afforded in Europe, but ultimately they were cut.

When I first learned about Empress Elisabeth a few years ago, I treated her almost like an indie band. “Oh, this is a very niche figure, she’s kind of my ‘thing.’” Of course, she’s actually a huge deal in Austria, and in Europe more generally. What was your experience talking to English speakers versus German speakers about this project?

I was lucky enough to get to go over to Germany and Austria to do a bunch of research for the book. German speakers, they’ve read too much about both of these characters, right? Maybe they were just being polite to me, but I feel like they were still very enthusiastic about them and still very attached to them as romantic figures. But they are more than familiar with these stories. When I talk to American friends, sometimes they have at least heard of their names, but it’s definitely more of a cult status here than it is overseas, where they’re kind of the main figureheads of those countries’ histories.

And of course, we’re in a moment where Sisi is getting an incredible amount of attention. That was impossible for me to know back in 2016 when I started working on this, but I’m game. I think she’s such an interesting figure. The more interpretations, the better.

$28.00

amazon.com

Yes! I’m thinking of the Sissi trilogy starring Romy Schneider, which are these rosy, nationalist films, and Visconti’s Ludwig, which is very decadent and intense. I’m wondering if you watched those, and whether the tone of your book was at all a reaction to those films?

I don’t think it was a reaction, because I started the work without having seen either of those iterations. But I do think they both present a dominant narrative of these figures. Sisi is almost kind of a Disney princess in the way that she’s portrayed in the Romy Schneider films. Admittedly I’ve only seen the first one. And Ludwig, I mean, what a beautiful movie. You know, very long, could probably be cut a little bit, but very dark and dramatic.

When I was doing the research and trying to figure out the approach that I wanted to take with this, one of the things that was driving me was all of those beautiful, fascinating, unbelievable facts from their lives. Around every corner there was something that just seemed absurd and impossible and too good to not include. Tonally, the narrator that was forming as I was talking about the events of the novel, it’s tongue-in-cheek, it’s anachronistic, it’s making comments on the story from a different point in history than when the story is unfolding. At the time the two movies that were in my mind were Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette and [Ken Russell’s] Lisztomania. And then The Favourite came out, and I was like, “Well, this is very close to the tone that I’m hoping for.” This book is a little bit more narratively fragmented than that, but that ability to bring some humor from the now into this moment of the past was what I was hoping to do.

Some reviews of this book call it a satire, which to me implies exaggeration. But as you’ve said, so many of the real details are already absurd. Sisi put veal on her face as a beauty treatment; she washed her hair in cognac and milk. How much of what you were writing was about inventing something that felt plausible, versus turning it up to 11 and really blowing it out?

Most of the stuff in the book is not invented. There are characters who are consolidated to make the story easier to track, and there’s some speculation into some of the relationship between people that I’ve changed or manipulated, but when it comes to their behaviors, the details or idiosyncrasies of their daily routines, or the way they treated those around them, most of that I could find some basis in historical documents. So I’m in agreement with you. I don’t mind the word “satire” being attached to the project, but I also feel like the story is almost just doing that on its own, in its own reality.

The reason that I feel like it’s okay to call reality a satire is because so many of the documents that I’m looking at are controlled by the palace and are potentially exaggerating the characters’ actions for a certain goal, or these documents are written by people who are trying to manage the narrative in certain ways. I’m trying to tell a truthful story that takes some liberties, but what is the truth when it comes to people who are so diligently and creatively trying to manage their own narratives?

And even with all that narrative control, there’s room for a lot of ambiguity. I’m thinking especially about the end of your book, where you give Ludwig an escape hatch—a sort of alternate, kinder narrative to the end of his life. Why did you do that? Was it a charitable impulse?

Maybe it was a little bit charitable. For all of his faults, I really love Ludwig and wish he had a happier end than he did. I don’t believe the ending I wrote, but because of all the speculation around his death, I was intrigued by adding another possibility to the mix. Because none of the others are happy, none of the others give him any relief or hope for a future. And, this is spoilers for anyone who’s reading, it allowed for Ludwig to have a tender moment of connection at the end of the story, where he and Richard Hornig are allowed to collaborate on something and show their care for one another, which was something that felt owed to both of them.

While we’re on that topic, I am curious: how much of Ludwig and Richard Hornig’s relationship was documented?

My understanding is that many of Ludwig’s journals were destroyed, but there are pages and letters. At one point in the book, Ludwig makes a monogram that mixes [his and Richard Hornig’s] initials together, and he will say things in Latin that he won’t say in German. He makes these commitments to chastity, and to not having any sort of romantic relationship with men, during moments when the royal calendar indicates that he and Richard had been together for an extended period of time.

That’s written down?

Yeah, every document that I looked at, every book and biography that mentions Ludwig, it talks about this long standing relationship that he had with his stablemaster.

Even the diary with the monogram?

Yeah, that’s real.

It’s a really sweet detail.

I know!

Something else I found really interesting was this split between public and private life for both Ludwig and Sisi. They live these incredible private lives, only because they’re expected to be public figures. Harry and Meghan might be the latest example of this dynamic of, “Look at us! But only on our terms!” Have the expectations of royals changed a lot since the 1800s, or is it just the same story repeating itself?

I think the politics of royalty have gotten easier. First of all, there are fewer royals, so there are fewer people that have to adhere to these standards. And it’s not as though the rules of royalty have not kept up with the times, at least insofar as they are equally behind now as they were then. It’s been moving along, but it’s still behind what it should be.

I have to be honest, I don’t follow British royalty. I’m of course aware of all the hubbub around Harry and Megan, but even looking at Sisi and Ludwig, these are incredibly privileged people, and there’s a limit to what lessons of empathy you can learn from these figures. Reconciling that is one of the reasons that there’s the narrative distance in the book that there is. It’s not a totally neutral narrator. It can be judgmental and recognize the hypocrisy of many of the things that they’re saying and doing. At least that’s my hope.

Sisi and Ludwig both seem obsessed with isolating themselves. Sisi more or less pulls this off, and Ludwig can’t. Does this come down to gender?

Yes, I think a lot of it is gender. For Sisi, being the wife of a ruler means that she was mostly expected to serve as a figurehead. She was expected to be more visible than she was, but when she chose to be visible, she served the purpose that was expected of her. With Ludwig, the reason he fails is because yes, he is the primary ruler of his region, but also because of the particular moment that Bavaria is in in at that time, kind of deciding the future of the German Empire: whether or not it will be consolidated, and where the lines of that consolidation will be, and his ambivalence in that face of that.

It’s kind of remarkable to look back and realize that the people of Bavaria never quite turned on him. They were maybe a little frustrated or confused, but for the most part, the historical narrative shows that politicians were really frustrated by him, and rulers of other German regions, Bismarck and Kaiser WIlhelm in particular, were very frustrated by his reluctance to do anything or hold a firm position. History has become frustrated with him, and his cabinet was frustrated with him because they felt he was neglecting his responsibilities to the point of the kingdom basically dissolving.

He just wanted to commission operas.

And castles, yes.

I think there’s a real queer sensibility to this book. Obviously Ludwig is what I would call a gay man, but he also has these escapist, fairytale fantasies that to me feel just as gay as his having sex with men. And Sisi could be a camp icon: she’s incredibly beautiful, and rich, and vain and imperious. I’m not asking whether Sisi and Ludwig are gay icons, exactly, but: do you think there’s a queer affinity about them, outside of their sex lives?

I think they are queer icons, right? I feel like they both have incredible followings in the queer community, and you know, they’re iconoclasts in their time. Even if Sisi was heterosexual, I feel like she is stepping outside of the boundaries of what’s expected of her. She's doing things that a woman isn't supposed to do at the time. So I think they’re absolutely queer icons. My hope with the book, and not approaching it from a traditional, fluid, glossed-over narrative approach, was that you could look at the stories of these characters with more complexity, where you’re allowed these spikey bits that you can’t reconcile with everything else. I feel like recognizing complexity and nuance and multiplicity is essential here.

You’re talking about complexity, but let me be a little reductive: do you think Sisi and Ludwig are tragic figures?

…Yes. Yes, because that’s my instinctive response to that question. But do they need to be? They both meet very tragic ends. But as far as the nature of their lives, there was nothing inherently tragic about the things that they were doing. I think they were both living their lives in the best way that they felt themselves capable of. The tragedy is that the world didn’t embrace those choices.

You Might Also Like