Remembering and Speaking “Frightful Wrongs”

“Nations reel and stagger on their way; they make hideous mistakes; they commit frightful wrongs; they do great and beautiful things,” wrote W.E.B. Du Bois. “And shall we not best guide humanity by telling the truth about all this, so far as the truth is ascertainable?”

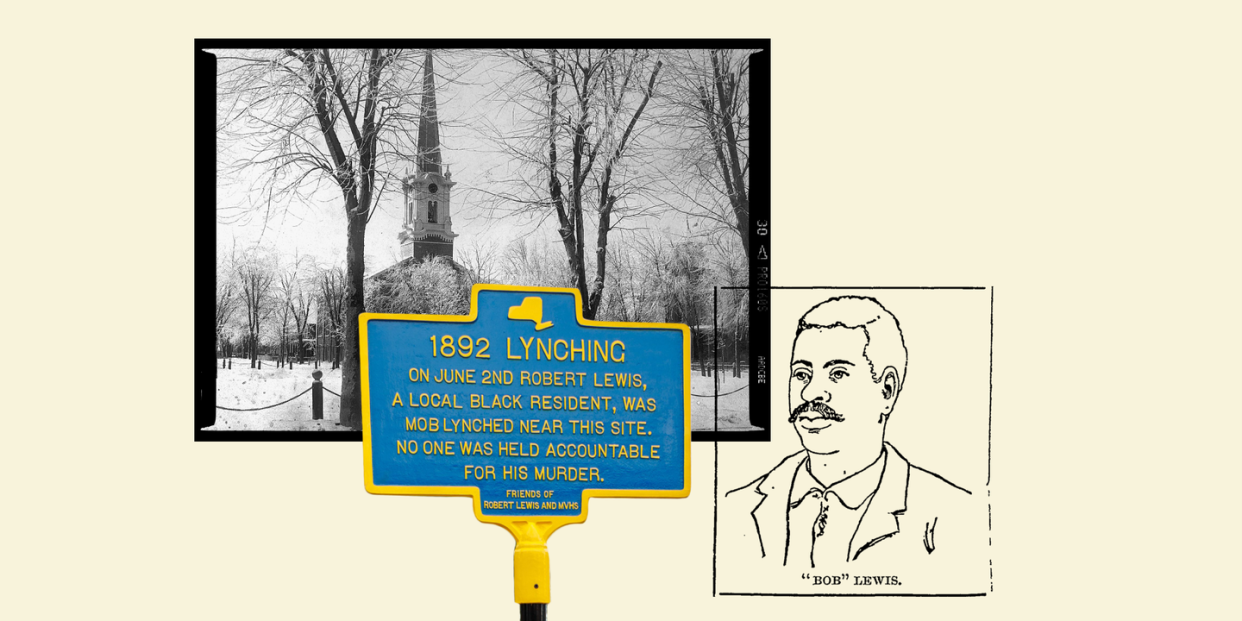

By Du Bois’s logic, memorializing the 1892 lynching of a Black resident of Port Jervis, New York, even 130 years later, would serve to guide humanity. A worthy effort. But on June 2 at the public unveiling of a plaque recognizing Robert Lewis and his murder, the questions left unanswered were “Did we wait too long? Do heartfelt words even matter?” Not even a full month earlier, 10 Black citizens of Buffalo, New York, had been shot to death at a supermarket by a white supremacist, drawing attention to the same insidious truths of 1892, that in the United States, racialized violence isn’t regional. Today, as at the end of the 19th century, the country is in a perilous place, where democratic norms are abused and abandoned, lies are rife, and determined forces would do away with the teaching of history and the remembering of “frightful wrongs.”

On June 2, 1892, Robert Lewis, 28, who drove a horse-drawn “bus” for a local hotel, was accused of sexually assaulting a young white woman named Lena McMahon as she sat reading a book by the riverside. Presumed guilty and denied due process of law, he was seized by a white mob and dragged up Sussex Hill to East Main Street, where despite the brave efforts of a policeman, the village president, and a judge to intervene, he was hanged from a tree before a crowd of 2,000 people, about one-fifth of the local population.

The incident was infamous at once, for it was perceived as a portent that the lynching of Black Americans, a horror then epidemic in the South, would extend its tendrils northward. "SOUTHERN METHODS OUTDONE," blared a headline. There had been a sharp uptick in these crimes—74 in 1885; 94 in 1889; 113 in 1891. The year of the Port Jervis lynching, 1892, would see the greatest number, 161—almost one every other day. This growing frequency of deadly assaults on Black people was compounded in March 1891 by the mass lynching in New Orleans of 11 Italian Americans suspected of complicity in the murder of the police chief; anyone, regardless of race or ethnicity, it showed, could fall victim to a mob.

It was in response to this crisis that in late spring 1892, at about the time of Robert Lewis’s death, the first national anti-lynching advocacy appeared in the writing of journalist Ida B. Wells and the legendary Frederick Douglass, and in a published resolution denouncing lynching signed by prominent civil rights activists and endorsed by New York Governor Roswell P. Flower and President Benjamin Harrison.

But what perplexed people up and down the Hudson Valley was why a lynching had occurred in Port Jervis, a prosperous community with a modest Black population of about 200 men, women, and children. And while the village was not free of the typical racial bias and inequities of the day—whites had in past years voted down a bid for local Black suffrage and forced Black people to move from a nearby reservoir out of concern they were contaminating the town’s drinking water—it had no flagrant history of anti-Black violence.

News of the Lewis lynching ran for weeks in regional and national papers, as local courts struggled, without success, to hold the mob’s ringleaders accountable. The white people of Port Jervis were not of one mind about what had occurred. There was shame at the barbarity of the lynching, one local paper conceding, “We never imagined such crimes could be enacted in this beautiful valley.… We mourn like a stricken household,” which was matched by regret for the damage to the town’s reputation. And while many disavowed the blatant illegality of the act, some thought Lewis deserved his fate. There appears to have been little, if any, outreach from white citizens to the traumatized Black community to apologize or make amends, and over the ensuing 130 years, Port Jervis came to observe a tacit silence about the matter, a hush that deepened as the community, at the confluence of the Delaware and Neversink Rivers, encountered social and economic setbacks, including the depletion of its once-thriving manufacturing sector and importance as a regional rail hub.

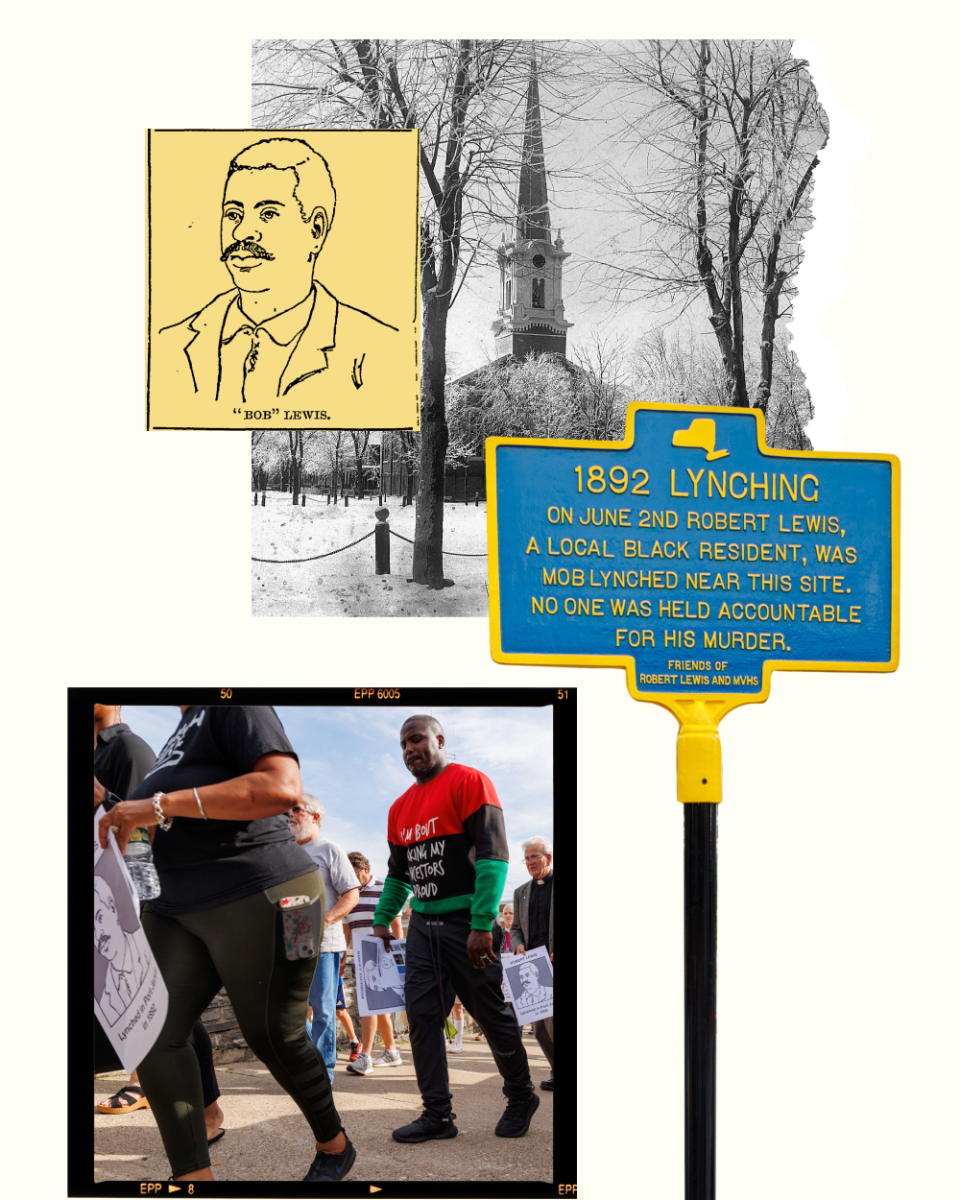

The June 2, 2022, commemoration of the event strove to bring Robert Lewis’s life as well as his death to the town’s attention. “There is no hero in this story,” observes Ralph Drake, one of the founders of the Friends of Robert Lewis, the group that supported the unveiling and the remembrance march that traced the route of the lynch mob. “The town must become the hero, in confronting its legacy.”

Port Jervis has now undertaken that important work, thanks to the Friends group, and, more broadly, the influence of the New York Times “1619 Project”; the work of the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama, which promotes a national focus on and dialogue about America’s history of racial injustice and its legacy; and the global impact of the Black Lives Matter movement. Three weeks after George Floyd’s murder in May 2020, local activist Arabia Shearn organized a dramatic biracial march through Port Jervis, past the site of the Lewis lynching and concluding in a large rally at historic Orange Square.

This year there was a different kind of silence on June 2, no longer of neglect and avoidance, but born of mourning and commitment to educate future generations about what had occurred. There was hope that the town’s public acknowledgement of a past wrong, represented by remarks from Mayor Kelly Decker and other dignitaries, may enable an increased recognition of local Black heritage and further engagement between all residents. As one speaker assured the crowd, all the hate and rage that surrounded Robert Lewis on that tragic afternoon in 1892 was conquered by the overwhelming message of love at this gathering, 13 decades later.

The unveiling of the plaque for Robert Lewis, and the uplifting speeches and songs that accompanied it, are essential to a community beginning a journey of healing and repair. But even as the town of Port Jervis came together to memorialize its painful history, residents and visitors are still mourning the deadly racist killing just a five-hour drive away in Buffalo.

As a historian, I believe we must rise to the challenge of our present by truly knowing our nation’s difficult history. The mistreatment of Black people in the late-19th century, of which lynching was only the most heinous manifestation, resulted from white fear—a fear of change, fear of the future, and of Black advances made possible by Reconstruction and competition over jobs, of Black enfranchisement, and the rise of elected and appointed men of color. This anxiety was expressed in white-authored theories of pseudo-scientific race science and insulting caricatures in daily newspapers, voter suppression, and in the white presumption of Black criminality and the related assumption of police powers by white vigilantes, often with the collusion of actual police.

Elemental to this dread was guilt among white men for their own centuries-long predation of Black women, which led them to place white women on a pedestal of sexual purity and to then criminalize and insist on the ultimate penalty for any perceived sexual transgression, relationship, or even passing flirtation between a Black man and a white woman. At the same time, white male dominance and patriarchy in society were sharply threatened, as a generation of young white women left the family farm to work in mills, move to cities, and gain independence.

Today, we are watching violence result from a somewhat familiar eddy of change and continuity. Where the Ku Klux Klan “organized” its white insecurity in the 19th century, we face not dissimilar anti-democratic forces. Our own age is one of amplified white grievance and anxiety over an anticipated “great replacement,” the growing role of women and people of color in society, a transformation in the ways people choose to identify by gender or sexual orientation, and even how children learn about our nation’s history.

And, as Buffalo and Uvalde remind us, today’s obscene frequency of mass shootings, which occur, as lynching once did, almost every other day, continues the historic connection between gun violence and white supremacy. Guns in the hands of whites enforced human enslavement, the Fugitive Slave Laws, the Black Codes of Reconstruction, and Jim Crow segregation, and enabled a world of vigilantism in which, as Du Bois noted, all Black men were presumed to be criminals and all white men were the police. Today’s owners of AR-15’s seem at times to cling defiantly to their military-style weapons as a kind of symbolic last redoubt against unwanted change.

Given these deep-seated structural faults, what difference can people of goodwill, of diverse ages and colors, marching together to honor the victim of a century-old lynching and vowing to educate the present community and future generations, possibly make? The answer, I believe, is everything.

Philip Dray is the author of A Lynching at Port Jervis: Race and Reckoning in the Gilded Age (2022) and At the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America (2002), which won the Robert F. Kennedy Book Award and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. He teaches in the Journalism + Design department at The New School.

You Might Also Like