Remembering Cara Croninger, Artwear Jewelry Maker and “Punk to the Core”

Cara Croninger

Cara Croninger, whose sculptural, brilliantly colored jewelry appeared in Vogue for more than 30 years, died last month. She was 80.

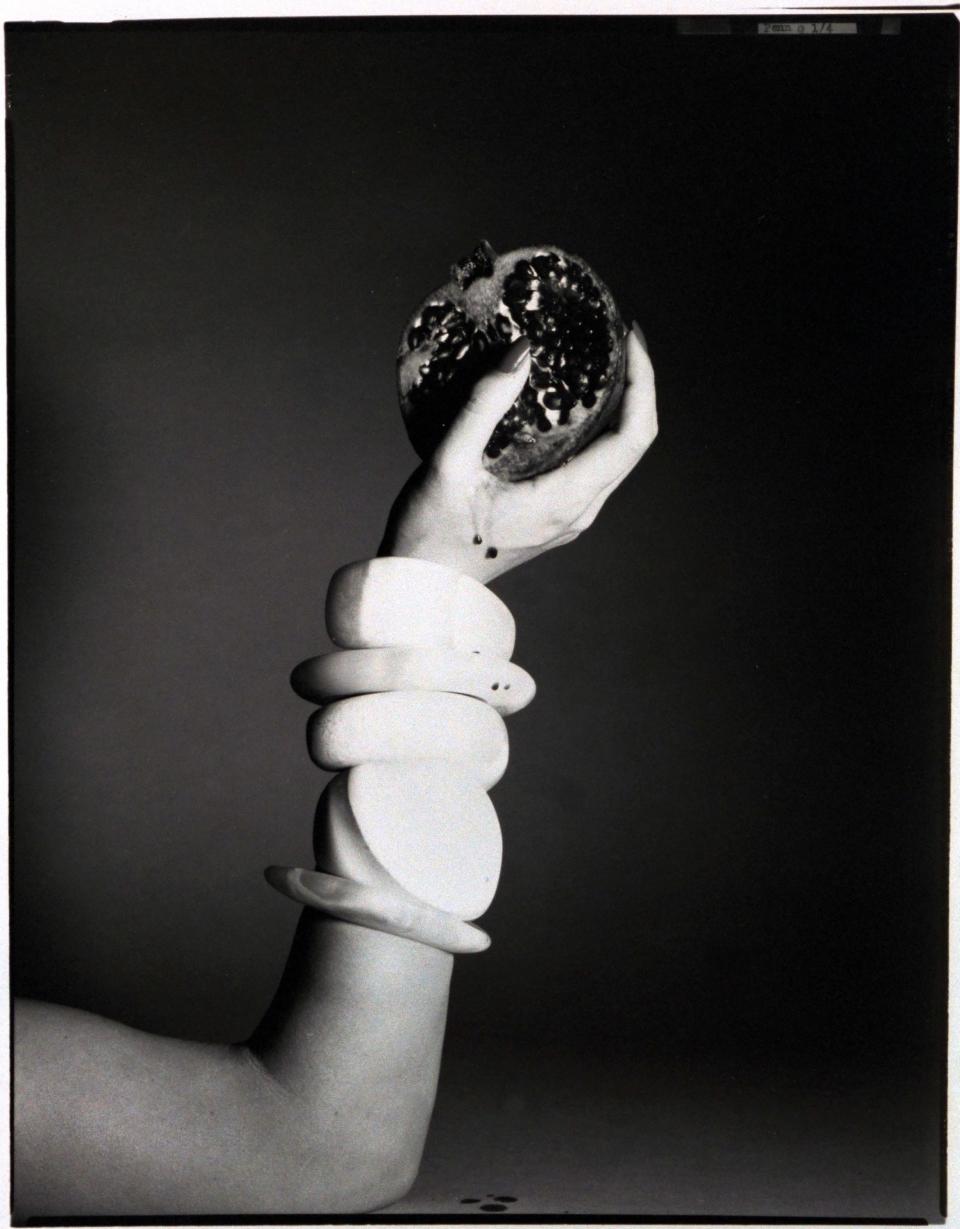

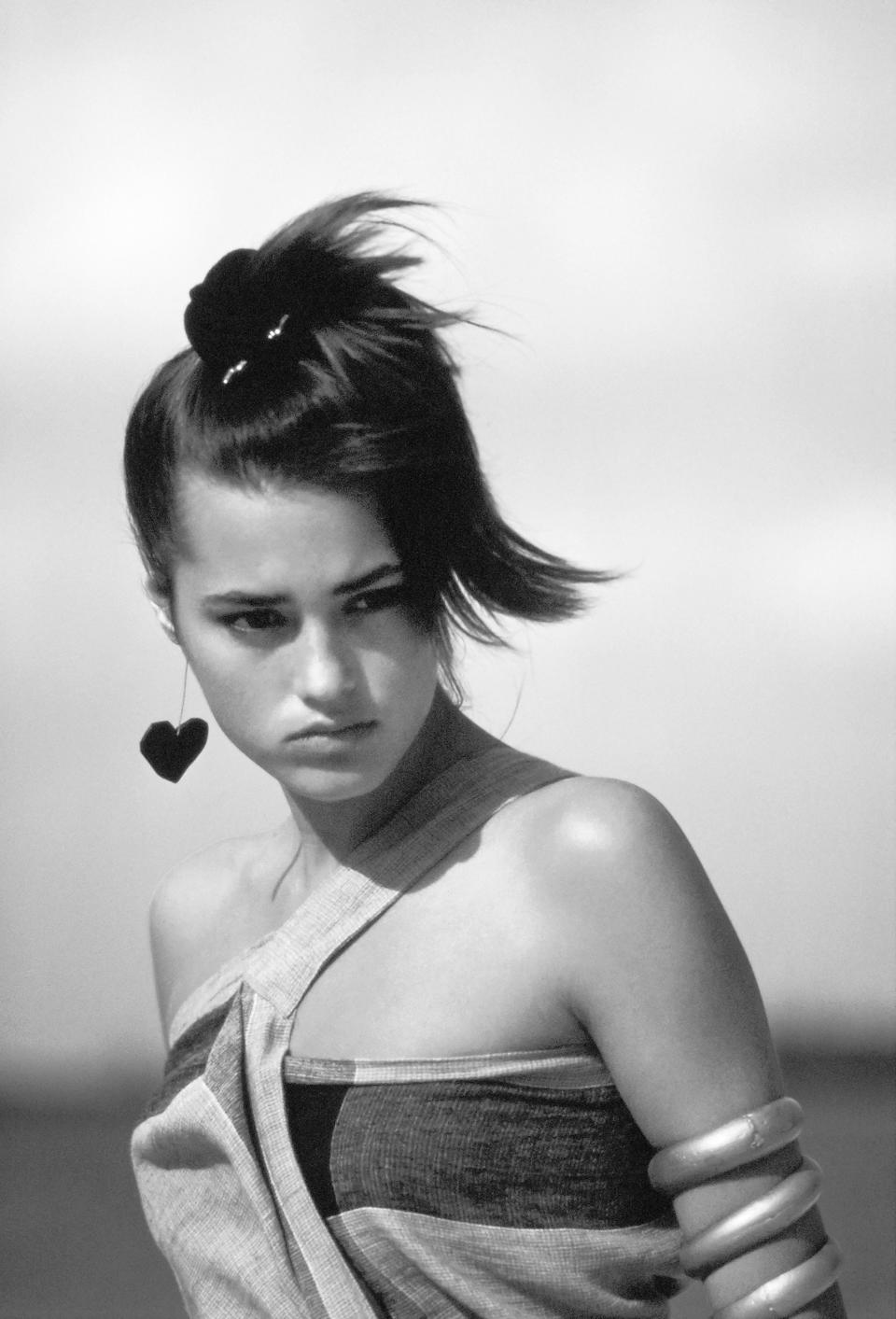

Raised on a farm in rural Michigan, Croninger liked making things with her hands. After a brief stint as a waitress in New York—she was fired and decided then and there never to punch a clock for anybody again—Croninger started working in leather, crafting obi belts and fringed and painted pouch bags that she sold on the street. A chance meeting with an artist who worked with plastics turned her on to the materials that she would use for the rest of her life: polyester resin and acrylic. She taught herself how to pour liquid resin and, once it hardened, carve earrings, bracelets, and what would become one of her strongest signatures, heart-shaped pendants, out of the stuff, taking cues from global jewelry traditions and tapping into the talismanic potential of body art. Her work managed to look both ancient and futuristic at once. Discussing her process with Vogue in 2009, Croninger said, “I like to think that there’s some kind of mystery to it.”

In the 1970s, Croninger sold her pieces at Sculpture to Wear, a gallery in the Plaza Hotel owned by Joan Sonnabend, who pioneered and championed the concept of artist jewelry. When it shuttered, a young designer by the name of Robert Lee Morris opened Artwear near the Whitney Museum to show his own work and that of his up-and-coming peers. Major stones in major settings were what resonated uptown; the expressive jewelry of Artwear, which was often rendered in cheap, non-precious materials, didn’t work on East 74th Street. “What is here,” Morris told The New York Times of the pieces in his glass cases, “is worth little except for its design.”

Once Morris relocated to West Broadway in a still-very-nascent Soho—circa 1977 only the gallerist Leo Castelli had established himself in the neighborhood, and there was zero retail scene—Artwear became buzzy, its openings attracting artists, rich collectors like Gianni Agnelli, and fashion designers. It was through Artwear that the jewelry designer Ted Muehling hooked up with Issey Miyake and Croninger with Geoffrey Beene.

“It was almost like a movement,” recalls Muehling of the Artwear gallery. “We were people of a similar age, poor and creative, going out on a limb.” He continues: “I was happy to show at a gallery where Cara was showing. Her work had a lot of guts—not Brutal, because it was tactile, but big scale. She was a fearless kind of person, and the jewelry reflected that.” Indeed, Croninger’s work required large machines—sanders, band saws—and she lived among them as she and her two daughters moved from one illegal, semi-converted industrial space to another in Tribeca, Gowanus, and Dumbo.

Her daughters grew up to become an actress and an architect. Says Saudia Young, her first child, “My mom was very influenced by African, Indian, and Asian design, by artists who inspired her like Isamu Noguchi, and spirituality and fetishes. I know at least one person who collected her heart pendants who took the heart with her into heart surgery. People relate to her work in a sensual, spiritual way. And that’s a reflection of her.”

Tom Binns also remembers Croninger from the Artwear days. “Cara, Ted, Robert Lee Morris—they were all the real-deal people, making jewelry as sculpture. It was what I was trying to do with my work: make art.” That resonates with a manifesto that Morris published in 1985, in which Croninger’s work had pride of place: “Artwear prizes aesthetic excellence above commercial viability. It applauds with equal enthusiasm jewelry that is lyrical and beautiful and jewelry that violates traditional form and explodes conventional boundaries.” Croninger exploded boundaries her whole life, not least of all because she was working in a field dominated mostly by men.

About a dozen years ago, Croninger met Patrick Bradbury, a PR man and showroom owner with a keen eye for jewelry who had helped Eddie Borgo and Bing Bang’s Anna Sheffield build their respective brands. Croninger agreed to let him represent her, and he placed her pieces in New York’s If Boutique and the Whitney Museum’s shop. The two lived not far from each other upstate and became close friends, sharing holidays. Bradbury took the photo of her that appears here on the day after Thanksgiving 2018, in the woods behind her Garnerville Arts & Industrial Center studio. The studio was a vast space of whitewashed brick walls and sash windows crowded with her jewelry, books, and collections of stones, old farm tools, giant wood dollies from her Tribeca and Dumbo loft days, and clippings of people and events that moved her, from the Russian feminist rock group Pussy Riot to stories about African Americans killed by the police. “I was extremely proud to have Cara’s pieces at Bradbury Lewis,” Bradbury says. “She was punk to the core, aggressive with color, shape, and size. She never followed fashion. Each piece was so singular.”

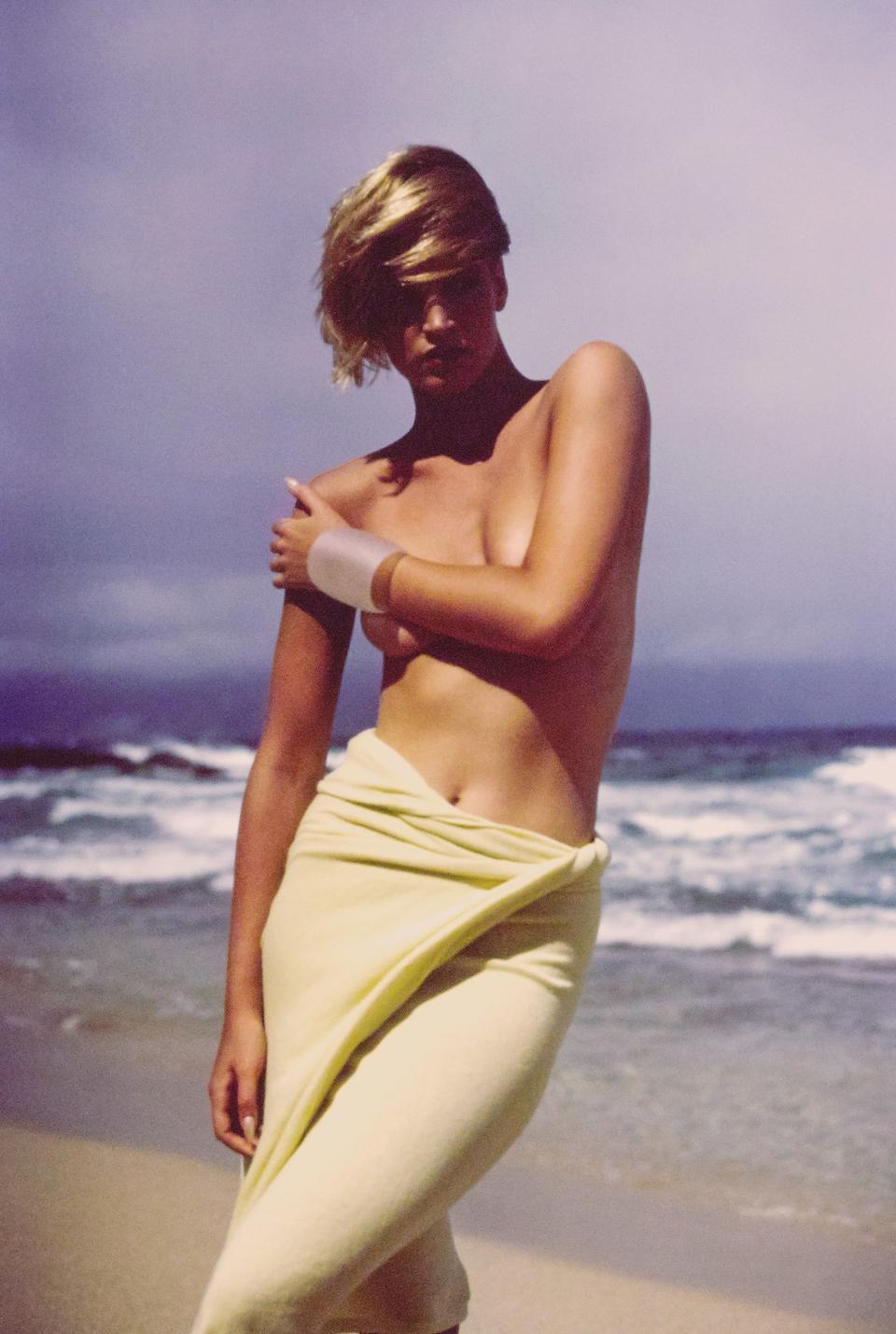

Over the years Vogue’s editors have tended to agree. Croninger landed the cover of the magazine in 1986. Richard Avedon shot Paulina Porizkova in nothing but two slashes of eye shadow and a bright pink Cara Croninger bangle on her left wrist. In 2016, the magazine’s former Fashion Director Tonne Goodman put Lupita Nyong’o in the jewelry designer’s acrylic earrings. Goodman remembers, “I started working with Cara’s pieces in the early ’80s when I was working at The New York Times Magazine. I was always impressed with them and loved them for their heft: size, weight, and attitude. They were organic, polished, chunky, modern. And obviously timeless.”