Remapping Australian Wine

Australia is arguably the world's most dynamic wine region right now, says F&W's Ray Isle, who spent weeks hopping between the Yarra and Barossa regions and found a new Down Under vision.

I'd heard of someone having a love-hate relationship with a wine before but never quite like this one.

A few months back, I was up at the Jauma winery, in Australia's Adelaide Hills, speaking with James Erskine, Jauma's owner. Erskine, a lanky former sommelier in his mid-thirties, runs Jauma out of an 1860s apple-picking shed, a ramshackle sandstone building crammed with barrels and the occasional cured ham (he hangs them from the rafters).

We'd been chatting about Natural Selection Theory, a kind of avant-garde winemaking collective Erskine was once involved with. A couple of years ago, the group was invited to participate in an exhibition of ephemeral art at a gallery in Adelaide. "We had a friend write a wonderful love poem and a vile hate poem," Erskine said. "I painted the poems by hand onto glass demijohns [six-gallon jugs] filled with a blend of Cabernet Franc, Grenache and other varieties. Half got the love poem, half the hate one." For three months, the love wine was displayed in a room where a recording played the love poem; in a different room, the hate wine was blasted with the hate poem. Finally, the wines were decanted into bottles for a tasting. "They were all sourced from the same original barrel," Erskine says, "but they were amazingly different. Love was so soft, so welcoming—yet fading fast. Hate was strong and steadfast, with a rich tannin line driving forward to infinity."

Of course.

There's no question that some people—many people—might find this project completely ridiculous. But I think there's something appealingly irreverent and truly inspired about it. And the experiment definitely reveals some of the wild, wing-it-and-see adventurousness going on right now in Australian wine.

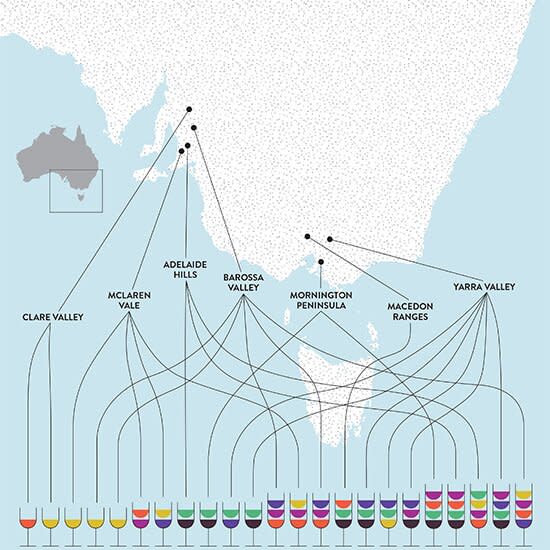

In fact, everywhere I went on my most recent trip to Australia I found young winemakers haring off in all kinds of unexpected, creative directions. Some were intent on changing classic styles—for instance, focusing on lighter-bodied, spicier, cool-climate Shiraz. Some were part of the burgeoning Pinot Noir movement, particularly in regions like the Yarra Valley and the Mornington Peninsula. And some were just heading for the far boundaries of the familiar, whatever that might entail—alternative varieties, biodynamic agriculture, non-interventionist winemaking, you name it.

This innovative approach to Australian wine is still quite small. Australia produces more than 125 million cases of wine a year, and only a tiny percentage exists on the edge. Yet the renegade winemakers offer an alternative to the all-too-common style of technically tweaked, cosmetically perfect, utterly nice, anonymous Australian wines that fade from memory as soon as they're gone from the glass (of course there are plenty of very good Australian wines, too, up to and including truly world-class bottlings like Henschke's Hill of Grace Shiraz, Penfolds Grange and Grosset's Polish Hill Riesling). The wines these mavericks make may only be a small drop in a very large ocean, but the influence they have is only going to increase.

Shiraz Or Syrah?

Everyone knows what Australian Shiraz tastes like, right? It's big and bold, rich with blackberry flavor, round and luscious. A liquid photograph of juicy grapes ripening to blackness under the hot sun.

Or maybe not. In the past few years, a new, cooler-climate idea of what Shiraz can be has come into view. Leaner, more peppery and more reminiscent of the savory Syrahs of France's northern Rhône (Syrah and Shiraz are the same grape), wines in this style are getting increasing attention, and in some cases great acclaim: Two of the past three Jimmy Watson Memorial Trophy winners—Australia's most prestigious wine award—have come from cool-climate regions. They're a savory corrective, in a sense, to the popularity of what McLaren Vale winemaker Justin McNamee of Samuel's Gorge described to me as the "ethanol-driven confectionary lolly-water" that populates the Australian sections of many wine stores. As a point of difference, some winemakers are even labeling their wines as Syrah rather than Shiraz.

Luke Lambert, in the Yarra Valley region northeast of Melbourne, is one of the stars of this movement. I met up with him on a blustery, overcast spring day, outside the Punt Road winery, where he makes his wines. Because—like most Americans—I'd made the assumption before leaving New York that Australia is always sunny and warm, I was freezing. "In my view," Luke Lambert said, "we should be making a lot more Syrah in this style. That is, raw." As he spoke, he was turning a very small knob on a very large steel tank. From a tiny spigot, he drained about an ounce of his 2012 Crudo Syrah into a glass, which he then passed to me.

Crudo is made to be fresh and lively, a kind of Australian nod to cru Beaujolais, though it's 100 percent Syrah. It has a kind of brisk energy that's incredibly refreshing, and it's definitely the sort of wine you can enjoy even while you're shivering. It's of a piece stylistically with his much more expensive flagship Syrah, a wine that he says "confused the hell out of people" when he took it on the road to Melbourne and Sydney 10 years ago. "A lot of sommeliers and wine shop owners thought it was faulty.

"Crudo's light, but it has layers and drive," said Lambert, who didn't seem to mind the cold at all. "I called it Crudo because it's a sort of metaphor for the wine and how it should be served and drunk, and what should be eaten with it. Wine should sit below what you're eating, not on top of it. The Italians had that right centuries ago."

The Rise of Pinot Noir

The desire for a more nuanced, balanced style of Shiraz is partly a natural pendulum-swing reaction to the robust, high-alcohol versions that were popular in the 2000s, but I think the awareness that a different style could succeed definitely owes something to the rise of Australian Pinot Noir.

Or make that the unlikely rise of Australian Pinot Noir. Not that long ago, it was easy to make an argument that Australia was the most significant wine-producing country incapable of producing worthwhile Pinot Noir. Vineyards were planted in the wrong places (a huge problem, given Pinot's gift for expressing vineyard character), and often the wines were oaked to death. Equally often they were jammy and flat, a kind of lumpen approximation of the shimmering delicacy that Pinot Noir ought to have. These days, though, there are superb Pinots coming from a variety of Australian wine regions. But the heartland of Australian Pinot Noir, now that there's enough of it to have a heartland, is Victoria, and particularly the Yarra Valley. I asked Yarra winemaker Timo Mayer why that was the case. He replied, "Because about 10 years ago a bunch of us woke up and asked ourselves, why aren't we making wines we want to drink?"

Mayer, a German expat who's been living in Australia for over 20 years, is only one of several extraordinarily talented Pinot Noir makers in the Yarra. Taken together, they're producing some of the most impressive Pinot Noirs I've tasted recently, not just from Australia but from anywhere in the world.

Mayer himself is a cheerfully blunt character, his German accent spiced up with Aussie colloquialisms (he refers to his vineyard as "the bloody hill" because, he says, "it's so bloody hard to farm the thing"). His wines, though, are subtle and nuanced. Mayer's 2012 Yarra Valley Pinot Noir, for instance, is aromatic, transparent ruby in hue, and savory-spicy. It's incredibly good.

Unfortunately, Mayer produces only minuscule quantities of Pinot Noir. Yarra winemaker Steve Flamsteed has greater reach—though he makes only small amounts of the high-end Giant Steps wines, he produces over 20,000 cases a year of Innocent Bystander. That's tiny by Yellow Tail standards, but it does mean that the wines are findable. They're also unmistakably Yarra: fragrant, medium- to light-bodied, but surprisingly structured. "When it comes to Pinot," Flamsteed says, "the Yarra doesn't naturally do 'big.' Instead we do perfume and elegance."

Natural Wines & Beyond

Cool-climate Syrah and Pinot aren't the whole story when it comes to this nascent Australian wine revolution. As I traveled around, I sometimes felt as though the success of those varieties, particularly in Victoria, had inspired other young, adventurous winemakers to more or less rub their hands in glee, thinking, Hah! If people will try Pinot, then who knows what else they'll try!

As a case in point, take Alpha Box & Dice. Located in McLaren Vale, AB&D looks more like a gonzo combination of a Victorian curiosity shop and a beachside taco shack than a winery, and in fact, during the summer months, it does partly transform into the Neon Lobster taquería, drawing mobs of young Adelaideans who devour tacos along with bottles of owner Justin Lane's wines. As for what those wines are, "all over the map" wouldn't be an inaccurate description. Lane makes a reasonable amount of Shiraz, but he's fascinated with varieties that are lesser known in Australia, such as Sangiovese, Tempranillo, Tannat, Nebbiolo and Touriga Nacional. Of course, being an extremely talented winemaker also helps, especially when your innate irreverence leads you to give your wines names like "Golden Mullet Fury" (which is a blend of Muscadelle and Chardonnay).

My trip to the outer edges of the Australian winemaking universe eventually led me, somewhat surprisingly, to Barossa, the region most identified with full-throttle Shiraz. It was there that I met up with Tom Shobbrook.

A slender, ponytailed guy with a lighthearted attitude, Shobbrook was one of James Erskine's compatriots in the Natural Selection Theory group. He tends toward what's been termed a "natural" winemaking style: minimal interference, little or no sulfur, no tannin additions, no acid adjustments, essentially making wine in as hands-off a manner as possible. His family's vineyard is farmed biodynamically; he works in a ramshackle old shed behind his parents' house. He makes a wide range of wines, under four different labels. Some, like the 2012 Shobbrook Syrah, are fairly straightforward—it has that classic Barossa blackberry fruit, just more gamey and wild. Call it the raised-by-wolves version. His 2011 Giallo Sauvignon Blanc, on the other hand, ferments on the grape skins for six weeks, then spends nine months in oak casks, essentially everything you're not supposed to do with Sauvignon Blanc. Hazy and golden-yellow, it's tannic, spicy, resinous and truly unusual. "Not everyone's kettle of fish," Shobbrook admits. "But it doesn't have to be. I just want people to try my wines. They don't have to like them."

The next evening, I found myself at a grand wine event, also in Barossa, on the other side of the valley. The venue was a beautiful old farmhouse belonging to one of the historic families of the region; it was rustic and vast, all dark wood rafters and glowing candles in alcoves on the walls. A vast spread of food occupied the center of the room. The guests included every major Barossa producer, the great and the good of the region, in a sense, and the whole thing had a bizarrely medieval feel. But to my surprise, at one point I turned and there was Tom Shobbrook, in jeans and a T-shirt, saying hello. "I didn't know you were coming to this," I said, pleased to see him.

"I'm not," he said. "I wasn't invited, actually. I just stopped by—a friend of mine spent the day roasting that pig over there."

But here's my prediction: Even if Australia's renegade young winemakers are the uninvited guests at the banquet right now, that's not going to be the case for much longer.

RELATED: Australia Wine Producers We Love