The Relationship Between Congress and Obamacare

Fact checked by Elaine Hinzey, RD

When it comes to information about the Affordable Care Act (ACA), otherwise known as Obamacare, it can sometimes be tough to separate fact from fiction. One example is the persistent rumor that members of Congress somehow exempted themselves from the ACA. This is entirely untrue, but it still resulted in a vast number of memes on this topic that have circulated on social media over the last several years.

This article will explain how the ACA works when it comes to health coverage for members of Congress, how these rules came to be, and how members of Congress and their staff obtain insurance for themselves and their families.

Obamacare Actually Applies More Strictly to Congress

First, to clarify, Congress is not exempt from Obamacare.

But let's take a look at how this rumor got started, and the rules that apply to Congress—which are actually more strict than the rules that apply to the rest of us.

Back when the ACA was being debated in Congress in 2009, there were questions about whether lawmakers were foisting the ACA's various reforms—including the health insurance Marketplace/exchange—on the American public without any impact on their own health insurance.

This was an odd concern, because, like most working Americans, members of Congress had employer-sponsored health insurance. So they weren't the people for whom the health insurance exchanges were created (i.e., people who don't have access to affordable employer-sponsored coverage or government-run coverage like Medicare, Medicaid, and CHIP).

But the ACA generated such a political firestorm that details like that got lost in the noise. The rumor persisted that Congress was somehow "exempt" from Obamacare.

The Back Story

Obamacare is just another name for the Affordable Care Act. So it's simply a law—not an insurance company or type of insurance. It applies to virtually all Americans and is much more far-reaching than just the exchanges.

It provides numerous consumer protections and includes substantial assistance to make health coverage more affordable for low-income and middle-income Americans. (The subsidies have been temporarily enhanced by the American Rescue Plan and the Inflation Reduction Act; the enhancements will be in effect through at least 2025.)

But in terms of what the law requires of individual Americans, it's very straightforward: People have to maintain minimum essential coverage. From 2014 through 2018, this was enforced with a tax penalty, although the penalty was eliminated as of 2019 (some states have created their own individual mandates with penalties for non-compliance).

Other ACA requirements apply to employers and health insurance carriers, but the requirement for individuals is just to maintain coverage. This requirement is still in effect, despite the fact that there's no longer a federal penalty to enforce it.

Minimum essential coverage includes employer-sponsored plans (even if the coverage is skimpy), Medicaid, Medicare, the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and individual market major medical plans, including those purchased through the exchanges or off-exchange, as well as grandmothered and grandfathered plans that pre-date the ACA or its implementation.

There are other types of coverage that also fit under the minimum essential coverage umbrella—basically, any "real" coverage will work, but things like short-term health insurance, accident supplements, and fixed indemnity plans are not minimum essential coverage.

Healthcare sharing ministry plans are not minimum essential coverage, but the ACA included a penalty exemption for people with coverage under these plans. There's no longer a federal penalty for being uninsured, but minimum essential coverage is still relevant in terms of qualifying for a special enrollment period (SEP) for an ACA-compliant plan: Several of the qualifying events are only SEP triggers if the person was covered under minimum essential coverage prior to the qualifying event. Healthcare sharing ministry plans do not fulfill this requirement.

Since most non-elderly Americans have coverage through their employers, they didn't have to make any changes as a result of the Affordable Care Act. As long as they have continued to have employer-sponsored health insurance, they have remained in compliance with the law.

That would have been the case for Congress too, since they were covered under the Federal Employee Health Benefits Program (FEHBP), which provides health coverage to federal workers.

Remember, the vast majority of Americans do not have to shop in the exchanges. The exchanges were specifically designed to serve people who buy their own health insurance because they don't have access to an employer plan, as well as those who were uninsured altogether.

As of early 2023, there were about 15.7 million people enrolled in private individual market health insurance plans through the exchanges nationwide—out of a population of more than 330 million people.

People with employer-sponsored coverage (which included Congress back when the Affordable Care Act was being drafted) do not have to deal with the exchanges at all, and there was no additional "red tape" for them under the ACA, other than checking a box on their tax returns stating that they had health insurance coverage throughout the year (even that was eliminated on federal tax returns as of the 2019 tax year).

The Grassley Amendment

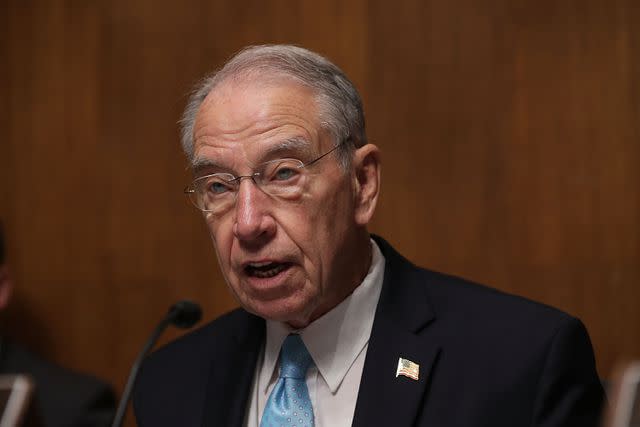

Section 1312 (d)(3)(D) of the Affordable Care Act, which originated as an amendment that was introduced by Senator Charles Grassley (R, Iowa) says:

"(D) MEMBERS OF CONGRESS IN THE EXCHANGE.—(i) REQUIREMENT.—Notwithstanding any other provision of law, after the effective date of this subtitle, the only health plans that the Federal Government may make available to Members of Congress and congressional staff with respect to their service as a Member of Congress or congressional staff shall be health plans that are(I) created under this Act (or an amendment made by this Act); or(II) offered through an Exchange established under this Act (or an amendment made by this Act)."

As a result, Congress and congressional staff have been purchasing coverage through DC Health Link's SHOP (small business) exchange since 2014. DC Health Link is the health insurance exchange for the District of Columbia.

SHOP exchanges were designed for small employers to use, but D.C.'s exchange is open to members of Congress and their staff, in order to comply with the ACA's requirement that they obtain coverage via the exchange.

Members of Congress and congressional staffers account for about 11,000 of DC Health Link's SHOP enrollments. This amounts to about 13% of the DC exchange's total small business enrollment, which stood at nearly 82,000 people as of mid-2021.

(All small group plans in DC are purchased through the exchange—unlike other areas, where most small group plans are purchased outside the exchange—so total enrollment in DC's SHOP exchange is much higher than in most other areas.)

What About Subsidies?

The ACA provides subsidies (tax credits) to offset the cost of premiums for people who shop for individual market coverage in the exchanges. But in the SHOP exchanges, employers provide subsidies, in the form of employer contributions to the total premium.

Where things got messy was the fact that members of Congress were previously benefitting from about $5,000 in annual employer (ie, the government) contributions to their FEHBP coverage if they were enrolled on their own, and about $10,000 if they were enrolled in family coverage. This is perfectly legitimate, and very much on par with the health insurance premium contributions that the average employer makes on behalf of employees: The average employer pays about 83% of the cost of single-employee coverage, and about 73% of the total cost of family coverage.

Switching to the individual/family market would have eliminated access to employer contributions, as the ACA forbids employers from paying for individual market coverage for their employees (this rule has been relaxed in recent years, via the expansion of health reimbursement arrangements).

But it would also mean that most of those folks—including virtually all members of Congress and many of their staff—would have lost access to subsidies altogether, since subsidies in the exchange are based on household income, and Congressional incomes are far too high to be eligible for subsidies unless the family is very large.

(As noted above, the American Rescue Plan greatly expanded premium subsidies, and the Inflation Reduction Act has extended these subsidy enhancements through 2025; some members of Congress and their staffers would have been newly eligible for subsidies as a result of this temporary expansion, but as described below, a solution already existed to protect their access to subsidized health coverage).

Keep Employer Contributions, but Enroll via Exchange

When the conundrum became apparent, the Office of Personnel Management (OPM), which runs the FEHBP, stepped in. They ruled in 2013 that Congress and Congressional staff, along with their families, would be able to enroll in D.C. Health Link's SHOP exchange and would still be able to keep their employer contributions to their coverage.

The ACA allows small employers (up to 50 employees in most states, and up to 100 employees in a handful of states) to enroll in plans through the SHOP exchanges. The Congressional staff obviously far exceeds this limit, and would not be considered a "small group" under any other circumstances. But the OPM rule allows them to obtain health coverage in DC's small group exchange, as this was viewed as the best way to address the problem.

This move was obviously controversial, with some people saying that Congress and their staffers should indeed have had to give up their FEHBP employer contributions and enroll in the individual market exchange, with subsidies only available if they were eligible based on income.

It should be noted, however, that Grassley himself said in 2013 that the original intent of the amendment was to allow Congress and staffers to keep the employer contributions that were being made to their health insurance premiums, despite a requirement that they enroll through the exchanges. Grassley contended that the amendment was poorly written after the details were sent to then-Senate Majority Leader, Harry Reid (D, Nevada).

(But it should also be noted that the ACA did not include any provision to allow employers to subsidize the cost of individual/family coverage purchased in the exchange, nor did it allow for large groups to enroll their employees in the exchange.)

Because of the OPM's ruling, Congress and their staffers still receive their full employer contribution to their health insurance premiums, but they obtain their coverage through the DC Health Link SHOP exchange.

This is a compromise that attempts to fulfill the requirements of the ACA, but without disadvantaging Congress and their staffers in terms of employee benefits relative to other similarly-situated jobs. There are no other large employers' workers who would have been forced to give up their employer's health benefits package as a result of the ACA.

The current situation came about as a result of language in the ACA itself that specifically referred to the health benefits of Congress members and their staff. Without that language, there would have been no question—members of Congress would never have had to shop in the exchange because they had employer-sponsored coverage.

That would not have meant that they were "exempt" from Obamacare. They still would have had to maintain health insurance coverage (or face a penalty until the penalty was eliminated at the end of 2018) just like every other American.

The exchanges were established for people who did not have employer-sponsored coverage (and for small businesses wishing to purchase coverage for their employees, although many states no longer have operational small business exchanges ).

However, because of the Grassley Amendment in the ACA, Members of Congress and their staff had to transition from their employer-sponsored health benefits in the FEHBP and switch instead to DC Health Link's SHOP exchange. This is a requirement that was not placed on any other sector of employees under the ACA, including the millions of other government employees who use the FEHBP.

So not only is Congress not exempt from the ACA, the law actually went out of its way to include them in a segment of the population (ie, those for whom the exchanges were designed) in which they would not otherwise be included.

Summary

Most Americans do not use the health insurance exchanges, but members of Congress and their staff are specifically required to use the exchange in order to maintain their employer-sponsored health benefits. This is the result of an ACA amendment that was sponsored by Sen. Chuck Grassley (R, Iowa), and it essentially means that the ACA applies more strictly to members of Congress than it does to other Americans who are offered employer-sponsored health coverage.

Members of Congress and their staff are still allowed to receive the normal employer contribution to their premiums that they would have received if they had continued to get their coverage through the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program (FEHBP). In order to make this work, they obtain their coverage through the small business portal of DC Health Link, which is Washington DC's health insurance exchange.

A Word From Verywell

If you hear someone say that members of Congress are "exempt from Obamacare," know that this is not grounded in reality. Under the ACA, members of Congress and their staff lost access to the FEHBP and had to transition to the DC health insurance exchange. The ACA did not require this of any other group of employees, including the millions of other federal workers who are still covered under the FEHBP. So not only is Congress not exempt from Obamacare; the law actually applies more strictly to them than it does to other Americans.

Read the original article on Verywell Health.