The Re-Re-Reinvention of Mark Wahlberg

*Editors Note: Men’s Health conducted its interview with Mark Wahlberg on May 1, 2020 for the cover of the July/August issue. The article has been updated to reflect recent and ongoing events.

It’s May 1, and Wahlberg has been sheltering at home for 39 days with his wife, Rhea Durham; his two daughters, Ella, 16, and Grace, 10; his two sons, Michael, 14, and Brendan, 11; and the family’s new addition, a Pomeranian named Champ who has 82,000 followers on Instagram and rules the house. The actor-producer-businessman, who once caused a disturbance on the Internet with a post about how he starts each day at 2:30 A.M. and schedules everything in 15-minute increments, rolls out of bed around 9:00. He eats a vegetarian breakfast, often plant-based sausage with a sweet-potato patty and avocado, washed down with three juice shots: greens, turmeric, and apple-cider vinegar with raw garlic and ginger. “Everyone hates it, because when I start burping, it smells like a restaurant.”

He finally heads down to his basement gym at 10:30 A.M. “That’s usually like my midafternoon lunchtime,” he says. “I’m still training five days a week, but now my wife is with me. I feel like I’m a human alarm clock. I’m pushing her to get down there. . . . The rest of the day, I’m eating more and drinking more wine than I normally would.” We’re on a Zoom video call, and Wahlberg is sitting at the desk in his home office. He's dressed in quarantine casual—sweatpants, a red T-shirt, bed head—fancied up with a crucifix on a chain. “I’m just maintaining until I get the word that we might be going back to work. Then I’ll get super disciplined again.”

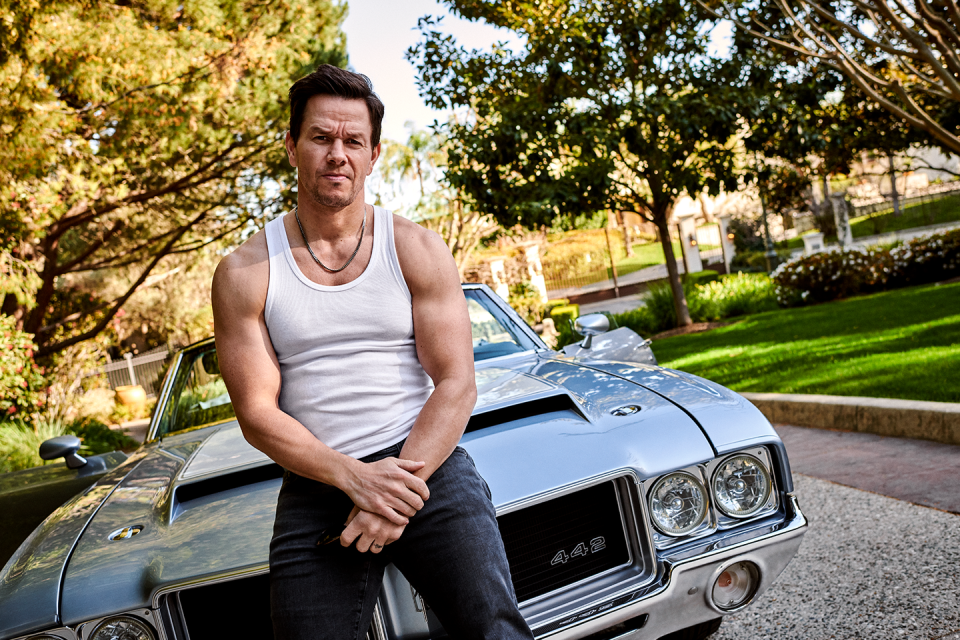

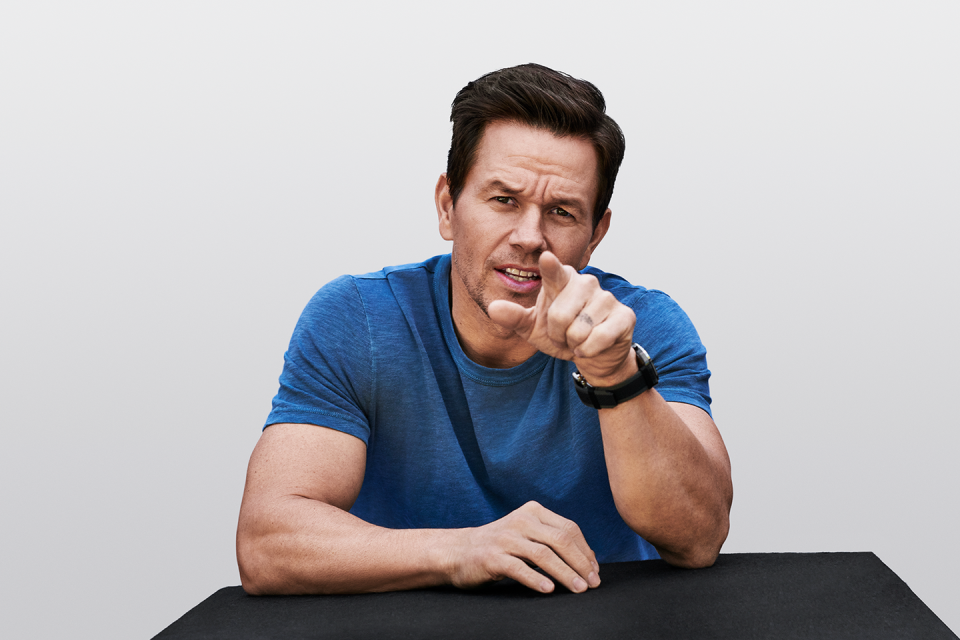

That discipline switch has been dialed up to 11—for the past 30 years—and it’s helped Wahlberg earn a unique place in our cultural memory and imagination. As Marky Mark, he rapped into our collective consciousness, buff and shirtless, with “Good Vibrations,” which hit number one in 1991. A year later, he helped make showing your underwear waistband a thing, posing in nothing but his Calvin Klein sport trunks. We didn’t really expect to see him again, but then he started acting. At first he popped up in minor roles, but he steadily earned bigger parts, shifting from gritty dramas to action blockbusters to raucous comedies. Often Wahlberg played characters who were larger than life yet still relatable. He’s the porn star with performance anxiety. He’s Optimus Prime’s buddy on Earth. He’s the Navy SEAL who survives a mission that kills his team. He’s the guy who fights with his best friend, a talking teddy bear.

In his spare time, Wahlberg stayed busy. He turned his early-career shenanigans into a hit TV show, Entourage, and created his first television-and-film production company. He is also a part owner of a burger chain, a gym chain, a supplement line, and a Chevy dealership. In July, he will launch an athleisure brand called Municipal. All this while raising four kids and being the most famous Catholic other than the pope. We’ve tracked his progress since 2005, having put him on the cover of Men’s Health six times—more than anyone else. It’s because he has big movies and big arms (and he sells well), but also because Wahlberg’s story shows how a flawed man who spent time in prison as a teenager can fix himself and keep trying to become a better man. In his case, fitness has served as a guardrail on that journey.

Now Wahlberg faces the challenges of juggling all his multiplatform projects and the demands of marriage and parenthood. Just looking at his schedule is exhausting. Even he says he works like a psychopath and has a boot-camp existence. Part of the appeal of getting older used to be that you could stop reinventing—you could slow down, settle in—and finally be yourself. You were good enough. At 49, he’s still going at it, and so are more and more of us. The idea of good enough isn’t always good enough. Then again, “good enough” was never good enough for Mark Wahlberg, which is why he’s Mark Wahlberg and not Vanilla Ice.

WAHLBERG GREW UP the youngest of nine children in Dorchester, a working-class Boston neighborhood where he mugged drunks, dealt drugs, and ran with a gang as a teenager. In June 1986, when Wahlberg was 15, he and two friends tormented three Black kids by throwing rocks at them and using racial slurs—twice, in two separate incidents over two days. A judge issued an injunction against him and his two friends for violating the civil rights of his victims—a hate crime.(That prohibited them from assaulting, threatening, or intimidating anyone because of race, color, or national origin. Violating the order would be a criminal offense). Thirty years later, in an interview with Men’s Health, he said people always asked him what he would he say to a teenage Mark Wahlberg if had the chance. He wouldn’t say anything, he reasoned, because the 16-year-old him “wouldn’t listen. He thought he knew it all.”

Then, in 1988, at around 9 P.M. on April 8, Wahlberg attacked a Vietnamese man who was carrying two cases of beer, shouted a racial epithet at him and hit him over the head with a stick, knocking him unconscious. While fleeing the police, he attacked another Vietnamese man and punched him in the face. Due to the violation of his previous civil rights injunction, he was prosecuted for two counts of criminal contempt of court, and sentenced to two years in prison. Wahlberg claimed he was under the influence of narcotics and alcohol at the time of the attacks and that the attacks were not racially motivated. He served 45 days in an adult jail.

Wahlberg says waking up behind bars made him realize he had made serious mistakes and caused people pain. “I got to a point where I said, ‘I don’t want to do this anymore,’” he told us in 2016. “I knew the only way I could be successful was by working hard and doing the right thing.” In prison, he learned training and prayer could give his life structure: pray, lift, eat, sleep, repeat. Focusing on his fitness and faith, and the discipline that comes with those things, pushed him to make better choices. That meant leaving the gang, working as a bricklayere, and taking ownership of his mistakes.

Part of that process meant apologizing for his crimes, something Wahlberg has done in court, in interviews, and in public statements. “In 1986, I harassed a group of school kids on a field trip,” he said in a 1993 statement. “Many of the students were African-American. In 1988, I assaulted two Vietnamese men over a case of beer. Racist slurs and language were used during these encounters, and people were seriously hurt. I am truly sorry for what I did.”

Wahlberg also expressed remorse in 2014 when he applied for a pardon to his 1988 conviction. In his petition, he wrote that he was deeply sorry for his actions and for any lasting damage he may have caused the victims. He went on to write that, “My hope is that, if I receive a pardon, troubled youths will see this as a motivation and inspiration that they too can turn their lives around and can be formally accepted into society. It would also be a capstone to the lessons that I try to teach to my own children on a daily basis.” Wahlberg dropped the pardon request in 2016 after encountering resistance including from some of his victims. One of the young women from the 1986 attack told the Associated Press, “If you’re a racist, you’re always going to be a racist,” she said. “And for him to want to erase it, I just think it’s wrong.”

In the petition, Wahlberg also noted that had he stayed on that path, “I would have likely ended up like so many of my childhood friends from Dorchester: dead or in prison for a prolonged period of time.” This ended up being the most important decision Wahlberg ever made, because without it, none of what came after (all the movies and money, all the fame and magazine covers) would have ever happened.

But he knows better than most that what’s done can’t be undone or forgotten. In the weeks after I spoke with him this spring (and after our print issue went to press), Wahlberg posted a photo of George Floyd on Instagram and Twitter and wrote, “The murder of George Floyd is heartbreaking. We must all work together to fix this problem. I’m praying for all of us. God bless. #blacklivesmatter.” Wahlberg then got the full “This you?” treatment on Twitter, with critics linking to the hate crime section of his Wikipedia page and calling him a hypocrite. When we followed up with him to ask if he had anything more to say, he did not respond. Perhaps he feels like he has said enough.

MUSCLE FIRST LED Wahlberg into trouble, then helped him escape it. He’d started strength training before prison because he was fighting so much, but committed to it even more in jail, and after he was released. “Instead of hanging out on the corner, I’d go the gym,” he told us in our 2005 cover story. “The gym was in the exact opposite direction of trouble.” Wahlberg’s trying to pass that gym discipline down to his children. “You know, it’s funny, because my kids came down to the gym today after the workout and my two sons are super athletic, but they’re like, ‘Oh, Dad, you’re a try-hard. You know, all you want to do is be buff.’ I said, ‘You should be training right now, too. You’re going to want to be in shape later.’” Even in quarantine, on a relaxed schedule, he’s staying fit, but his approach has changed from that of his 20s.

In those days, his training emphasized mirror muscles, with iconic results. See: the Herb Ritts–shot Calvin Klein ads from 1992. More than a decade later, our 2005 cover story noted, “Wahlberg hits the iron hard, but in the simplest ways. He picks two or three body parts to focus on for 30 minutes five days a week.” “My head was hard,” he says, referring to his old regimen. “A lot of people that I worked out with would be amazed where my focus is with my training now: No more isolation movements. It’s got to be fully functional.” He also spends more time stretching with a foam roller or TRX, targeting his “quads and hammies, the psoas, all the uncomfortable stuff that takes stress away from my back.”

The training he did at 10:30 was a “big, functional F45-style workout,” he says, referencing the Australian-based gym chain known for group classes that combine strength, mobility, and cardio. Last year, Wahlberg became a part owner of F45, which has more than 800 franchises in the U. S. He says he went to a class and “fell in love with the workouts.” He was struck by the scalability—an older overweight newbie was doing the same workout as a college athlete—and the upbeat, communal vibe. The people were inspiring one another, and it seemed like a saner, safer version of CrossFit.

He’s also a part owner of Performance Inspired, a supplement company he founded in 2016 with a former GNC executive. It’s a fitness and wellness play, with training and recovery products made with high-quality natural ingredients. Compared with brands that make wild marketing claims with images of XXXL bodybuilders, it’s basic (but in a good way).

Wahlberg admits that he gets obsessed with new workouts and diets, partly because he’s had to put on or take off weight for roles. “The fun thing about my job is that it’s constantly forcing me to challenge myself and change,” he says. His record low weight was 137 pounds, for The Gambler in 2014. “I was 138 pounds for Boogie Nights [in 1997] and I had to beat that number,” he says. “I went on a liquid diet for six weeks and did 200 rounds of jump rope every day.” His heaviest was 212 pounds, for Pain & Gain in 2013.

Currently he’s eating a plant-based diet five days a week that makes it easy to keep his weight close to his quarantine target of around 180 pounds. Wahlberg was in London last year filming Infinite, a 2021 sci-fi thriller directed by Antoine Fuqua. He was doing the Full Wahlberg—waking up at 2:30 A.M. to train, eating every two and a half hours—but “by the time I went to work, I was just tired.” He consulted his doctor, who suspected he had leaky-gut syndrome and put Wahlberg on a bone-broth cleanse and then a steamed-vegetable diet. Soon he was feeling much better, and because he’s “a creature of habit,” he leaned into plant-based eating, supplementing with lots of plant-based protein shakes. He goes wild on the weekends, adding “a little pasta and fish.” “Between work, I want to grow and evolve and be in the best possible shape for life,” he says. “That’s being strong, mobile, flexible, no inflammation, feeling good.”

THE MOST DRAMATIC reinvention in Wahlberg’s career was playing Dirk Diggler, a well-endowed porn star, in Boogie Nights.“It was a risky move: With my background, with Calvin Klein, was it just me being exploited?” he says. “It was cool to be tough or edgy, but it wasn’t really cool to be vulnerable. It was also liberating.” It’s not clear if he’s talking about acting or real life, but it applies to both. Paul Thomas Anderson’s film demonstrated that Wahlberg could handle meaty roles with emotional depth and that he was leaving behind the chest-beating machismo of the old neighborhood. He was skinny, fumbling, with doofus hair, and he had to say lines like “I just can’t get it hard. I just can’t. I’m sorry.” It turned out there was more to Wahlberg than crotch grabbing and an eight-pack.

Other directors took note, and soon Wahlberg was working with David O. Russell, Tim Burton, and Martin Scorsese. Wahlberg, like fellow Boston royalty Tom Brady, has always felt he’s had something to prove. (For the record, he says he wishes Brady all the best in Tampa Bay. “Tom won six championships and was two plays from winning eight. If it’s Tampa versus the Patriots in the Super Bowl, I want the Patriots.”) Brady was the 199th draft pick; Wahlberg was typecast as a rapper and model. Brady still taps into those feelings to motivate himself every game; Wahlberg sees every movie as a chance to prove he belongs.

“I was willing to work harder than everybody else,” he says. “You do whatever it takes to become the part. So that means if you got to go to a SEAL boot camp for two weeks or you got to go on a fishing boat and hunt for tuna.” That applies to comedy as well. “I don’t practice pratfalls in my living room to see if I can be funny, but I have the same approach. I want to be the character and play it as real as possible.” Just as Brady relies on his game smarts over physical gifts, Wahlberg has a psychological edge, too. “I felt like I had an advantage because of my real-life experience, which allowed me to tap into things that other people would have to use techniques and things that they learned in theater school to be able to do.” As with his physical training, he’s found a method that works, and he tinkers with it for each new role.

Given the success Wahlberg has had in different genres—his three highest-grossing domestic movies are the action blockbuster Transformers: Age of Extinction (2014), the comedy Ted (2012), and the drama The Perfect Storm (2000)—I ask if he has three favorites. It’s not an ego-stroking exercise but meant to probe what’s closest to his heart. After a long preamble, noting that every movie is a group effort and there’s no individual credit, he says (here’s the heavily condensed version): “Three is tough, but I gravitate toward the true stories. Boogie Nights [1997], Lone Survivor [2013], and The Fighter [2010].” It’s revealing because it shows how he’s balanced personal preferences with more marketable options, and it speaks to his affinity for men who do dangerous jobs.

I ask if he can imagine taking a risky role, like Dirk Diggler, now. He pauses, then starts talking about Good Joe Bell, a movie he recently shot with director Reinaldo Marcus Green that was written by the Brokeback Mountain team. It’s based on the true story of Jadin Bell, a 15-year-old who was bullied for being gay and took his own life. His dad, Joe, played by Wahlberg, vows to walk across America to raise awareness for Jadin. “I’m playing a very conflicted, complex individual. But I think that makes it more relatable to the people that we really want to change and to open their eyes and their hearts to accepting people no matter where they come from or what their preference in any aspect of their life is, whether it be sexual, religion, any of those things. There’s a lot of people who don’t get it, unless they see somebody like them and they put themselves in those shoes.”

Back in 2005, Wahlberg told Men’s Health he looked at his acting career like an athlete does and that there was a short window of peak performance—he alluded to six years. He’s now more than double that, and he’s stretching that window by embracing new kinds of roles. He reaches across his desk and shows me a black binder with Uncharted written on it. “I was attached to a movie for a decade called Uncharted, which is based on the video game, playing Nathan Drake,” he says. “This is the actual script. Cut to now and I’m playing the old guy. Yeah. Tom Holland is Nathan Drake! There are certain people who kind of try to hold on to youth, and you have these kinds of weird movies where older guys are paired up with younger actresses, and we all know how unfair that is. I’m more driven now than ever before, and I’m also more comfortable in my own skin.”

The secret to Wahlberg’s constant reinvention may be that there’s no secret at all—it’s just the only way he knows, and to not hustle, to not wake up at graveyard hours or have six full-time jobs, would somehow be a betrayal of his code. Plus, he’s worked relentlessly to earn his current status, and now he’s more able to choose the projects he really wants to do, which is something we all aspire to. And there’s his ego. “When people come into this business, you look at the Hollywood issue every year in Vanity Fair and they anoint the Next Guy, right?” he says. “A lot of those guys didn’t become The Guy. There’s only a handful. I’m The Guy who is still around, still doing it, you know?” It’s not meant as a flex, more as an observation, but it’s a flex.

“It’s one thing to have a career and wake up every day thinking, Okay, what’s the next job?” Wahlberg told us in his 2010 MH cover story. “But I want to build something that can last forever, something that my kids could venture into if they’re interested.” That was when he was still just an actor. Wahlberg’s reinvention as a business guy follows his tactics as an actor—trust his own experience. With his production companies, Closest to the Hole and Unrealistic Ideas, that means shows Wahlberg either lived or would watch: Entourage, Boardwalk Empire, Ballers, and McMillion$, the HBO show about the McDonald’s Monopoly-game scam. With Performance Inspired and F45, it means supplements he takes and workouts he does. With Wahlburgers, it means food he wants to eat (now including the Impossible plant-based burger). “I have to live it, and it has to be a direct extension of who I am,” he says.

Wahlberg’s next venture is Municipal, an online clothing brand somewhere between Lululemon and Supreme that he’s creating with CEO Harry Arnett, who previously worked at the golf company Callaway. “The goal is versatility: It’s the clothes you wear 95 percent of the time in the gym, at home, at work,” says Arnett. “It’s orientated around the inclination to move, literally and as a metaphor.” But because Wahlberg is baked into the identity of the brands, he has to stay relevant and keep starring in big movies to drive growth.

It’s telling that Wahlberg has said the actor who most inspires him is Paul Newman, because of his philanthropy and business smarts. He’s thinking Big Picture. “All the success and all the things that I achieved, guess what?” he says. “You can’t take it with you. There’s no luggage racks on a hearse, right? What do you do with it? How do you make the most change and move the needle in the most ways? I didn’t have to look any further than out my window where I grew up. I didn’t have to say, ‘Is there a crisis in the world that I can get involved with—you know, rain forests, animals, and all this stuff?’ ” That’s why he supports the Boys & Girls Clubs of America through his foundations and why his businesses have philanthropic components. All told, The Mark Wahlberg Youth Foundation has raised more than $10 million dollars for various organizations nationally and he has served as a board member on the Boys & Girls Clubs location in Dorchester.

He seems dedicated to being a role model and helping kids avoid making the mistakes that he made.

That Wahlberg’s upbringing is so different from his own kids’ is intimately wound up in what motivates him and who he says his hero is: his dad, Donald Wahlberg, a Korean War veteran and truck driver who delivered school lunches. Wahlberg was introduced to film through his dad, who showed a teenage Mark old gangster movies starring guys like Steve McQueen, James Cagney, and John Garfield. “It was so pivotal in so many ways. My dad worked hard just to put food on the table. He showed me what hard work looks like, and I knew what it smelled like when I sat with him in the yard. He was sitting in his garden and he wouldn’t flick cigarette ashes onto the yard, because that was the only home he’d ever owned. He would flip them in his pant cuffs.”

Wahlberg is trying to inspire that same blue-collar work ethic in his kids, but from his Beverly Hills chateau with a swimming pool and a basketball court. “I’m sitting across from my son, just yesterday, having this conversation, and I’m like, ‘Dude, if you don’t work hard in school right now, you will regret it later. You always give it 110 percent, then you’ll never have to live with regret.’ I’m speaking from experience. I’ve got to instill that ethic; if you want to make something happen, the only way to do that is to roll up your sleeves and do the work.”

It’s obviously something he’s wrestling with, because he furrows that famous brow and keeps talking. “What I want to give them is the drive and desire to find out what they’re passionate about and go and be the best version of themselves. Maybe one will want to go into acting; others may want to take over one of these companies that we’re building. And one may say, ‘I want to be a professional skateboarder.’ ”

He continues, “My faith and all that weighs heavy on me, too, in a good way, to inspire them. I don’t force them to go to church with me every Sunday. And this is the first time I haven’t gone since my wife has known me in 19 years. They know that it’s the most important thing for Dad, like that’s how he starts his day, every day. So hopefully those things will rub off on them.”

Wahlberg takes the responsibility seriously. In 2010, he spent 35 hours at the dermatologist, lasering off his tattoos—Bob Marley, the rosary beads, and the one of Sylvester the Cat with Tweety Bird in his mouth, which he got when he was 17 to cover up the shamrock tattoo he gave himself when he was 12—to set a better example. He did add a tiny new tattoo on his ring finger on Valentine’s Day in 2016. “It’s my wife’s name, Rhea,” he says. “She says it’s the best gift I ever gave her. When I’m away or working and can’t wear my ring, she is still with me.”

Having a daughter made Wahlberg see women through a different lens. “My firstborn being a girl completely changed me,” he says. “I have friends with only boys and they’ll be like, ‘Check that out’ or ‘Look at her,’ and I’ll say, ‘Dude, have some respect; that’s somebody’s daughter.’ ” From Marky Mark to proud #girldad, it’s not a small step. It’s a giant leap.

One thing his kids don’t follow his lead on is crying during movies. He’s a famous crier, and I ask how he got to a place where he’s comfortable tearing up in front of his children. “It’s real life, dude,” he says. “There are many, many times when my kids will tell me, ‘Dad, whatever you do, don’t cry.’ But I tell them there’s nothing wrong with crying, with conveying those kinds of emotions. When I watch a movie that feels real and emotional, it just gets me; it gets me every time.”

Wahlberg brings up his dad again at the end of our interview, when I ask when was the last time he cried. It wasn’t at Donald’s funeral back in 2008; it was actually just the previous day, recalling how a dear friend’s father had been in the hospital for six weeks and had just passed away. Because of the pandemic, the son wasn’t allowed to visit. But he had written a letter to his dad and emailed that letter to Wahlberg, saying he was feeling depressed. So Wahlberg FaceTimed him.

“I’m sitting in my bathroom looking at this picture of my dad with my oldest son, knowing that my youngest son never met my dad and my youngest girl never met my dad. And thinking about mortality, thinking about my mom, who just took a terrible fall, and I had snuck home to see her. Even though she had busted her teeth, her mouth, and her eye, she was in great spirits, even with what’s going on in the world. There’s this uncertainty that I’ve never felt. Sharing that loss with my friend, I was trying to just remind him that even if you live to 150, life is short. But I have a firm belief that there is a better place and there is a heaven, and that his dad and my dad were sitting there introducing themselves and that if we do the right thing in life, then we have that—so celebrating his life and all that stuff. We just both had a nice little cry, shedding happy tears for the guys who meant so much to us.”

Not long after, my time is up and he has another call, but before that, his kids are pushing to get in a game of hoops. It’s a Friday afternoon, and there’s the weekend with fish and pasta on the menu, virtual mass, and hang time with Champ to look forward to, as Mark Wahlberg works on the mostly serious but sometimes funny business of being better than good enough.

You Might Also Like