Refusing to Censor Myself

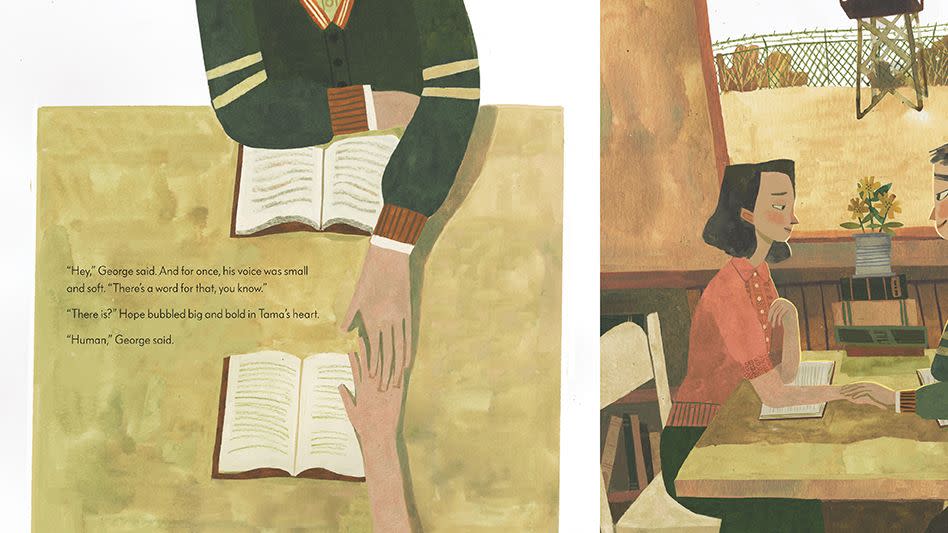

There are a few things I’ve always known about the world and my place in it. The sky is blue. My grandparents met in a prison camp for Japanese-Americans during WWII. I don’t remember the first time I was told their story: Tama was the camp librarian, and George would go in every day and check out big stacks of books he had zero intention of reading so he could flirt with her. They fell in love there, in that prison camp, against the backdrop of virulent racism.

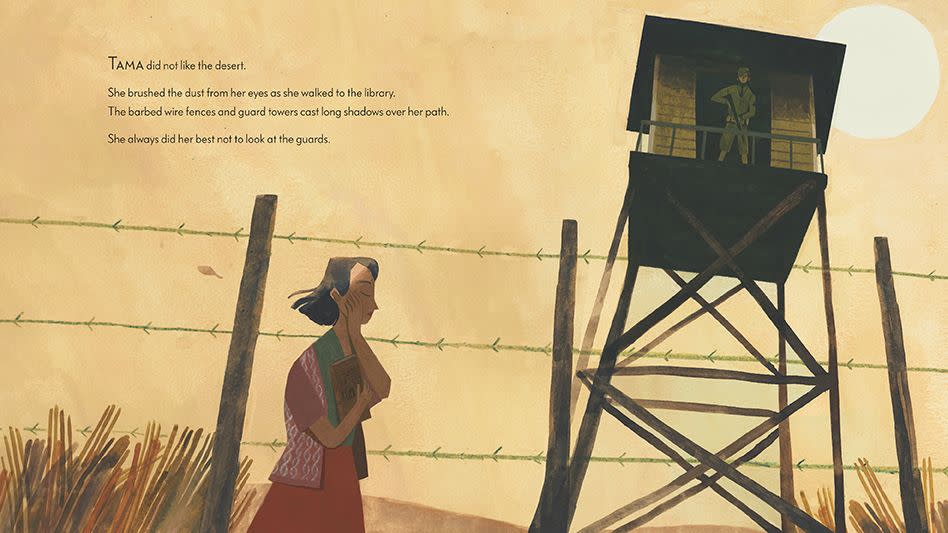

When I decided to write a children’s book about them, I purposefully wrote a picture book, the format intended for our youngest students. I did this because I know that children can understand the full emotional complexity of my grandparents’ story. And I did it because I also knew kids needed to hear about perfectly legal, state-sanctioned violence at an early age. The book I wrote would become Love in the Library, illustrated by the incredibly talented Yas Imamura, and published in 2022 by Candlewick Press. It was a critical darling of its year, but sales were modest.

So when I received word from my publisher that Scholastic—the biggest children’s publisher in the country, whose book clubs and education divisions have direct reach into classrooms all over the nation—wanted to license our book for an educational initiative, I was thrilled. But all of this was tempered almost immediately. The licensing opportunity was contingent on a cut being made to the book’s author’s note.

In the author’s note, I situate what happened to my grandparents in American history. Which is to say, I call it racism. And I draw parallels between the violence of Executive Order 9066 and other incidents of state-sanctioned racist violence in our history and our present. I invoke the family separation policy on our southern border. Reference the Trail of Tears. And I was very purposefully inclusive of police brutality against Black Americans. The note is a very incomplete list of racist policies enacted within our nation—there’s no mention of the Chinese Exclusion Act, Indian termination policy, or Operation Wetback, for example—but this is simply because there was not enough room in the book (or this essay) for a complete recounting. There are simply too many instances to name.

Scholastic’s proposed edit, which I was told I needed to accept to be given this licensing opportunity, cut that whole paragraph out with an unbroken red line. And not only that, but the word racism had been excised from the author’s note altogether.

I emailed my agent about how offensive the offer was and how disgusted I was. Then, unable to sit still with my fury, I texted her. I was going to say no, an absolute and categorical no, that much was for sure. But also: On a scale of one to that lady who bought all of her own books to manufacture a presence on the New York Times bestseller list, how much would it ruin my career if I came forward about what I’d been asked to do? Because I suspected I wasn’t the first marginalized author who’d been asked to make this kind of edit, who’d been limited this way, who’d been forced to choose between opportunity and their own morals.

Later that night, I told my husband what had happened. He’s a problem solver by nature and wanted immediately to find a compromise. It was a big opportunity, after all. He didn’t want me to miss out. But as I showed him the edit, pointing—look, see?—even he had to admit there was no compromise to be had.

“You’re doing what’s right,” he told me. “You’re being brave.”

And that’s when I started crying.

I didn’t want to have to be brave. And how deeply I resented Scholastic then. For putting me in that position. For forcing me to choose. For the opportunity I knew I was losing. For the fear that, in going public, I’d harm my career, maybe forever. Our industry is based so much on reputation; I cannot get away with being considered “difficult to work with.” How often had I heard just that about other authors—usually women or queer people, but especially women and queer people of color—whispered behind closed doors? I knew and know what a death knell that can be.

And I cried out of the transparent frustration and fury of it. That I knew, I knew I wasn’t the first author this had happened to. That so often marginalized creators are called upon to lend our biographies for credibility, but to stifle our voices for marketability.

I am hardly unique in this. Over drinks and in the DMs, writers of marginalized communities swap our horror stories. Our books will be rounded up for listicles promoting Pride Month or Black History Month or AANHPI Heritage Month, our identities the focal point rather than our work. And how disheartening, to know that we will always be limited this way. Our marketing budgets are smaller, we know this. We’re less likely to be sent on tour. We know this. We are less likely to have advanced reader copies, an essential promotional tool, made for distribution to booksellers and reviewers. We know this.

And we know full well that our invitation to the stage is conditional. We were brought up there in response to the public demand for diverse books. But we’ll get the hook as quickly as the backlash becomes more vocal. Publishing, our dubious ally. Publishers want our suffering, smoothed down and made safe and palatable for the white readership they prioritize. And if that readership refuses to acknowledge the existence of transgender people, Blackness, or racism, then. Well.

The language Scholastic had used in the email made it clear. “This politically sensitive moment,” they called it. “Beyond what some teachers may want to cover.”

They were worried about the rising culture of book bans. And they thought that if they simply excised that portion of my author’s note, they might be able to play two sides at once. To feature my book and pay lip service to the demands for diversity in children’s books, while also appeasing that small but ever-louder contingent of parents and politicians who, out of fear, contempt, or political expediency, seek to ban those same books. They were trying to thread a needle. To pay lip service to DEI initiatives while also trying to accommodate book banners. But they are trying to exist in a center that will not hold.

We are not so far removed from the time when we taught our schoolchildren that slavery was good for the slave. That it was honorable to kill the Indian to save the man. Or that Japanese-Americans were put in the camps for their own safety. These lies were taught regularly in schoolbooks because that was what the market demanded. And now we find ourselves being forced to resist the comfortable pablum of jingoism once again.

There is no appeasing this vocal minority, nor should there be an attempt to do so. This is an existential threat to all of literature, one the publishing industry should be combating, not cowering before. If we cannot depend on the publishers of these stories to defend the truth, if they cave to the political pressure manufactured by the few to the detriment of all, then we are truly lost.

The backlash Scholastic faced after I went public was swift. They recanted, offered me an apology. They also offered to license Love in the Library in its full form. But my concern was no longer limited to my own story. This book had become a stand-in for so many that are quietly limited in this way. And without an honest recounting of what had happened, without concrete steps to avoid this in the future, without a realistic plan for how to combat book bans with more than milquetoast memos, I did not feel I could accept. Publishers may be the gatekeepers to our careers. But they cannot exist without us. They have no product without us.

We do not owe them our obedience.

You Might Also Like