Who Really Profits When We Retrofit Diversity Into Our TV and Film?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Welcome to Critical Thinking, a series where we discuss one thing in pop culture that's really been irking us lately, and why you should care about it.

Last fall, I wrote an op-ed about how House of the Dragon failed its Black characters, propping them up as diversity figureheads only to kill them off in five episodes. As expected, I received hate mail from both Black and non-Black readers calling out “reverse racism” that I dared suggest the HBO show only cast white actors. But here's the thing: Putting more people of color on-screen, while a valiant effort, doesn't magically solve Hollywood's diversity problem, especially when the people behind the screen (i.e. the minds behind your favorite TV shows) are mostly white.

We’re in the era of reboots, spinoffs, and IP-developed TV. Book fans and TV fiends are witnessing a parade of their favorite novels adapted into television with inclusive representation as an added touch—House of the Dragon, Harry Potter, the upcoming Percy Jackson, and the latest, Queen Charlotte, which is part of the Bridgerton universe. Hollywood is doing what it's always done: taking existing content (books) and repackaging it for the screen (TV and movies). Only now these showrunners are retrofitting diversity into their adaptions in response to audiences demanding more representation. Hence, the current (and long overdue) Black and brown takeover in TV and film. Listen, I love seeing more faces like mine on TV, but I can't stop cringing at the tweets and TikToks praising these white authors for “diversity” when they didn't write their books that way to begin with. I mean, white authors are receiving social and financial clout for what authors of color have always done. You can't tell me that's not weird!

Beverly Jenkins—an author who's written African American historical romances since the '90s—doesn’t need her work to be updated like Julia Quinn’s Bridgerton. Jenkins’ characters are Black and thus written as so. Yet it is Quinn’s work that was chosen to be adapted into TV, reconstructed with actors of color, and then praised for its diversity. Quinn receives both financial rewards (the show is certainly helping to sell her books) and social recognition, too. To be clear, she's not responsible for the choices of the entire entertainment industry, and she's also not making all the creative decisions behind the adaptations of her work. But there's a pattern happening here. Quinn is not the only white author in this position. Just look at The Umbrella Academy creator Gerard Way, who rose to global popularity thanks in part to his amazingly-created work that, when adapted, featured an inclusive cast.

Quinn and other white novelists deserve these opportunities, and I don't blame them for wanting their work to be adapted for a larger audience. And it would be problematic if, in 2023, these casts were all-white. But where are the adaptations for Black and brown stories? Correct me if I’m wrong, but they look to be sitting on the bookshelves while the white books are on screen. Akata Witch by Nnedi Okorafor has been dubbed the Nigerian version of Percy Jackson, but where's her adaptation? Disney+ would seemingly rather reboot Percy Jackson and change Annabel to Black than bring something like Okorafor's book to the big screen. Same goes for Vanessa Riley's Rogues & Remarkable Women—a Bridgerton-esque trilogy featuring all Black leads finding love in the most unexpected circumstances.

Hollywood keeps bringing literature to life and I love them for it, but it’s almost always white literature, and even Black showrunners like Shonda Rhimes have contributed to this reality. They probably know firsthand what I assume to be true: that walking into a pitch meeting with an idea based on a white story gets a “yes” much faster than an idea based on a Black story.

What happens when you put white stories on-screen and make them diverse? Because Bridgerton was so bingeable, I ran to my local bookstore after I watched it and bought The Duke and I. Imagine my surprise when I realized how quickly the publishers put Regé-Jean Page on the cover despite the book not getting any update whatsoever. I was like, huh?

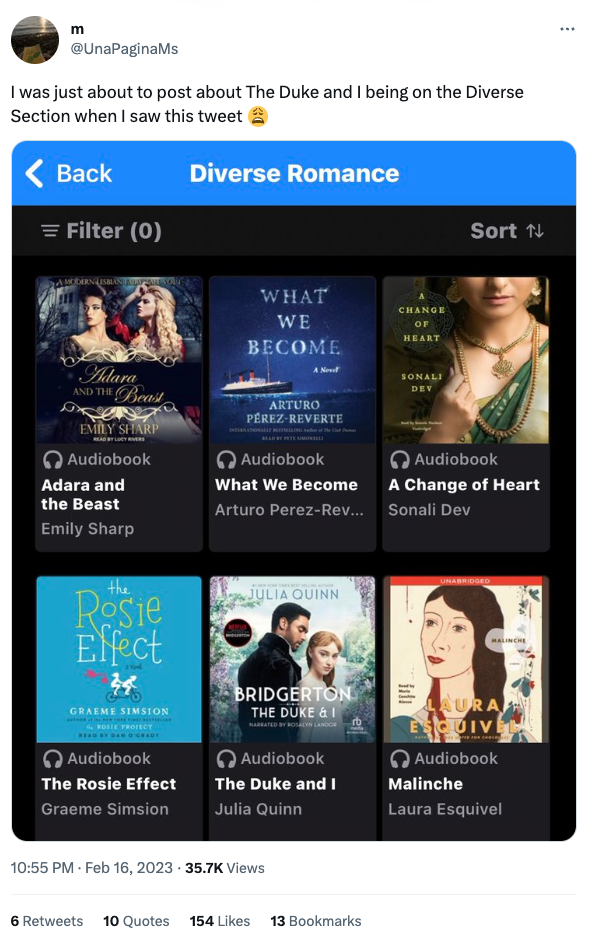

I’m not the only one who has had this kind of uncanny experience. Amazon and other book retailers have now classified the Bridgerton series as “diverse reads” even though the novels feature zero people of color. Honestly, sometimes I feel tricked after I've given money to white authors under the illusion that their books are like their TV shows.

There is no easy solve for this problem, but if Hollywood would adapt diverse stories at the pace that it does white stories, it would at least be a start. Representation is about more than giving white stories a melting-pot makeover—it’s about giving stories written by authors of color some sunshine too so that we don't have to shoehorn "inclusion" into where it didn't exist in the first place. The entertainment industry might make the argument that authors of color are not as well known as white authors, but that’s not an excuse. Inclusion is a conscious effort that requires maybe a few more marketing dollars, but it's worth it.

Do you know how many young Black and brown readers would be ecstatic to have their favorite romance novel turned into an eight-episode series or feature film? To know that Hollywood is *finally* valuing the Black romance authors whose books they've read since they were teenagers? Or think about the young children of color who are aspiring authors and could grow up believing their stories are also worthy of being told on TV?

That is representation. Keep diversifying television, but let’s also reward the already-diverse stories out there. Authors of color like Okorafor, Riley, and Jenkins deserve their flowers too—they’ve done the work for years and raised generations of readers. So Hollywood, I’m calling on you to give some stories of color an adaptation. Might I suggest The Boyfriend Project by Farrah Rochon? Or The Brown Sister series by Talia Hibbert? There's also Ace of Spades by Faridah Àbíké-Íyímídé and Grown by Tiffany D. Jackson. But you don't need to take it from me. If you're looking for adaptation inspo, just spend a few minutes on BookTok and you'll see that people are already obsessed with so many diverse reads. Catch up.

You Might Also Like