What Really Happened to Little Edie After Grey Gardens

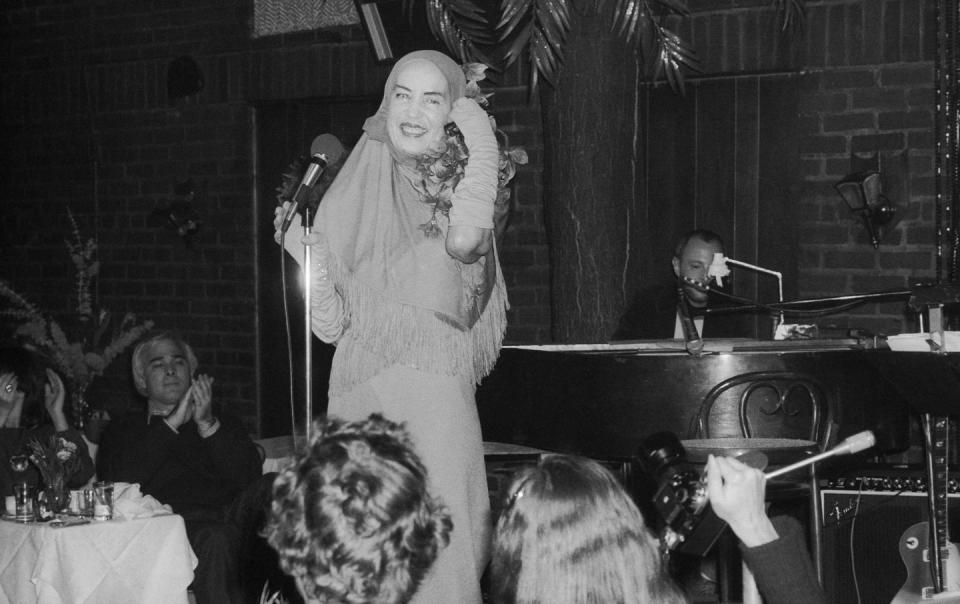

On New Year’s Day in 1978, Edie Beale was onstage at the Greenwich Village nightclub Reno Sweeney, crooning “Tea for Two,” a riot of red feathers atop her head. The evening may not have taken the exact form of the Grey Gardens star’s long-held dreams of fame, but after 25 years of living in seclusion with her mother, it was more than good enough. “I'm finally beginning to live!” the New York Times reported her as saying a few days later. “This is a priceless opportunity for me. At the end of my 12 performances, I will know a little more about myself, and what I should do in life.”

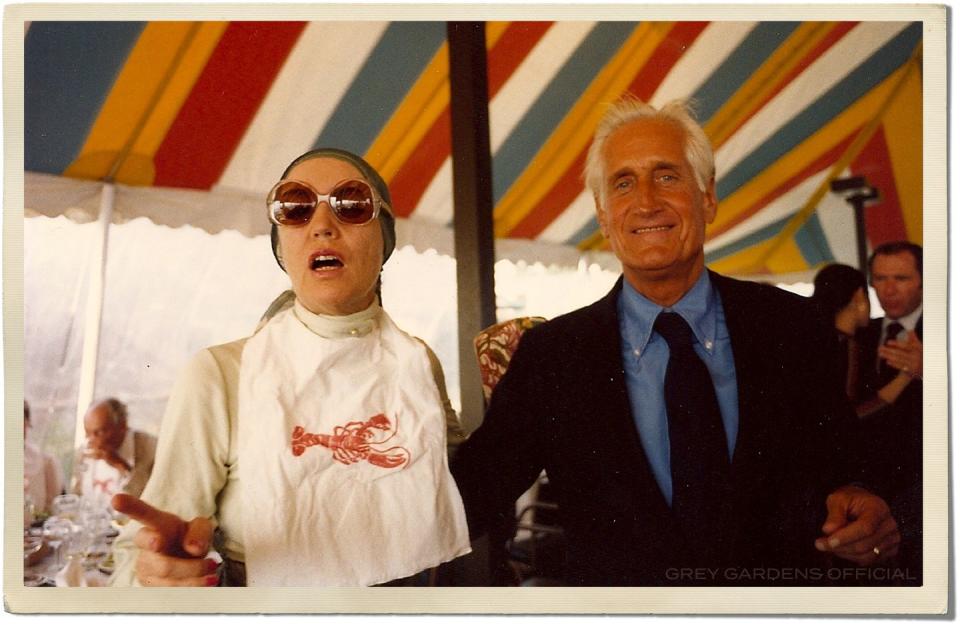

Beale performed six shows to a packed crowd of friends, devoted fans of the 1975 documentary and, reportedly, luminaries like Andy Warhol and Truman Capote. “She was never a fantastic singer, but she was sure a great show person. She was a wonderful performer, and she sang songs and then put little bits of her life in between the songs, and so on,” says Muffie Meyer, who co-edited and co-directed Grey Gardens. “The audience was obviously predisposed to love her, but she was completely charming and it was a huge success.” Those who knew her believe it was one of the greatest periods of her life.

You wouldn’t know it from the reviews, which were vicious. “Miss Beale has said that she does not feel that she is being exploited. That may be true. If anyone is being exploited, it is the customer who pays a $7.50 cover charge to suffer a public display of ineptitude,” John S. Wilson wrote in The New York Times.

“I remember that there was something around the Reno Sweeney time that someone implied that it was like a crazy person making a spectacle of herself,” says Meyer. “But I don't remember that she was upset by that. I'm sure if she said anything about it to anyone, they would have easily tried to convince her out of being upset, because the crowd at Reno Sweeney's was in love.”

Less than a year earlier, Edie had lost her mother. The Edies, a mother-daughter pair whose deep eccentricity—and the squalor of their life in a crumbling East Hampton mansion—made Grey Gardens such a hit, were no more.

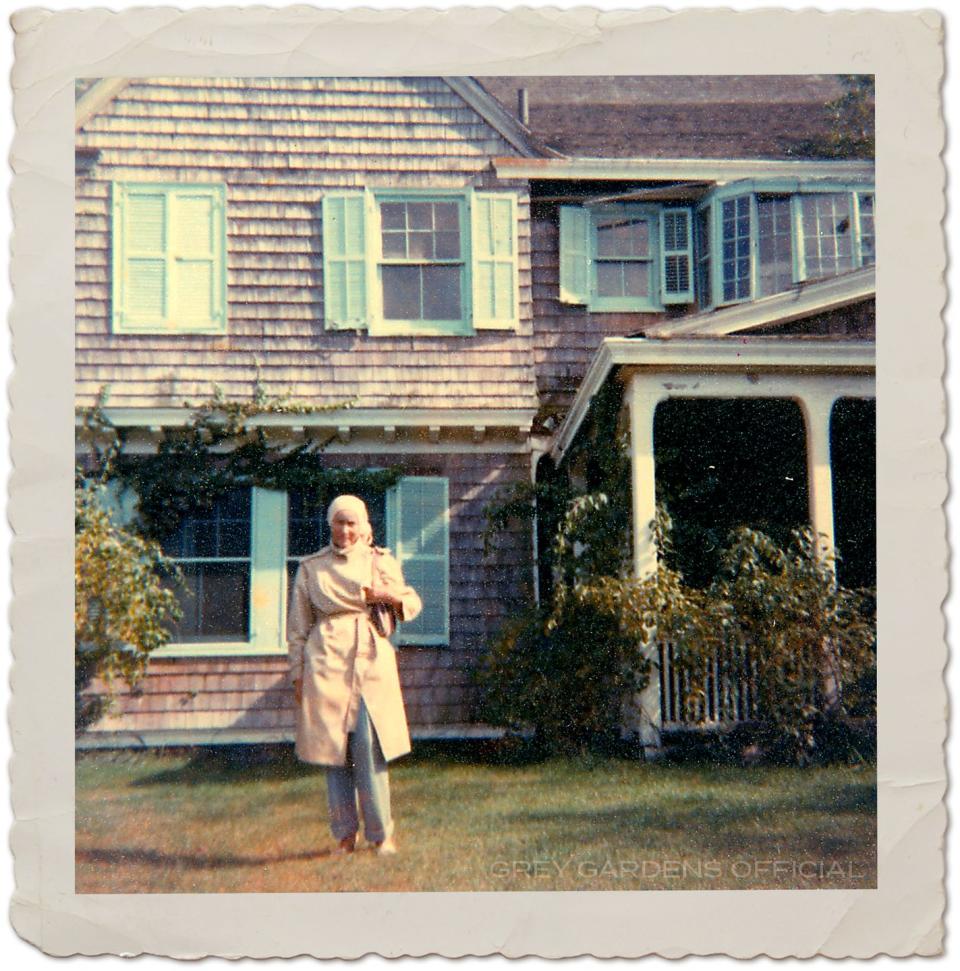

Over the following two decades she’d sell her famous home, relocate to New York City, and live in Florida, Canada, and California. She never stopped moving. Kent Bartram, who is writing a biography of Little Edie called Staunch Character, refers to Edie’s post-Grey Gardens life, which began in her 60s, as “her second debutante season.”

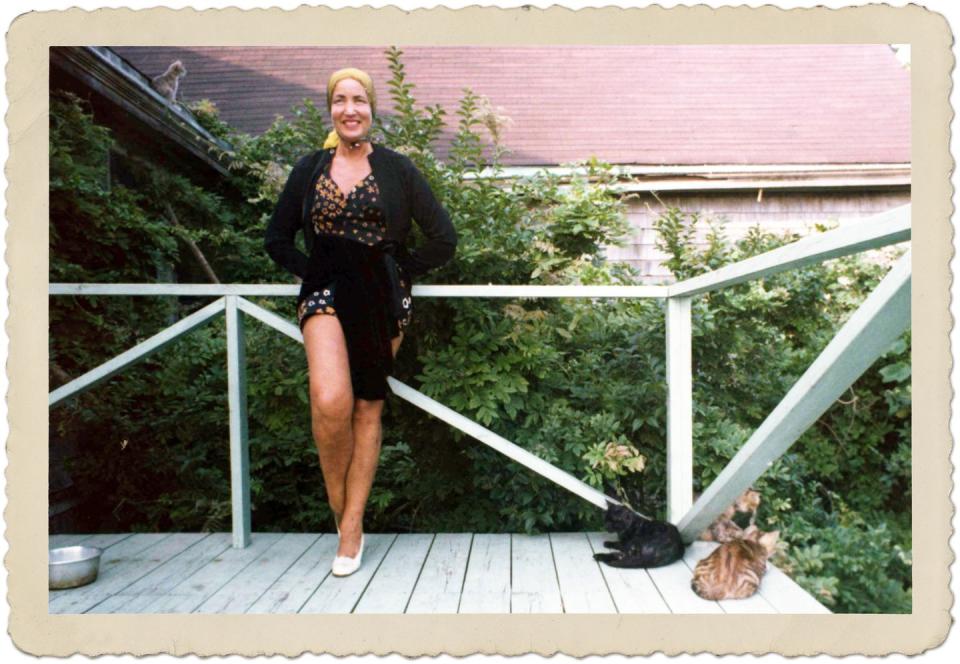

Born and raised in Manhattan, Little Edie, famously the first cousin of Jacqueline Onassis, was a long way away from her days at Miss Porter’s School and the Barbizon Hotel when documentary filmmakers Albert and David Maysles made her acquaintance in 1972. Her father, Phelan Beale, left Big Edie in the 1930s and provided scant financial support. In 1952, after years spent modeling and pursuing show business fame in New York City, Little Edie returned home at age 34 and spent the next 25 years living in relative isolation with her mother, a large pack of cats, and the occasional raccoon, their formerly grand home decaying around them.

The Beales became notorious in 1971 when a police raid uncovered a high level of squalor and the county health department threatened them with eviction. It was reported at the time that Jackie and her sister Lee Radziwill contributed thousands of dollars that allowed the Beales to fix up the home and pay off some back taxes.

The Maysles were introduced to the Edies through Radziwill and quickly knew they’d found a subject they couldn’t walk away from. They were fascinated by the pair’s faded glamour and uniquely intense—some would say dysfunctional—mother-daughter relationship and began filming Grey Gardens in 1973.

The Beales are mercurial and uninhibited, pouring out their regrets to the camera and sniping about each other’s failures. They’re sentimental, nostalgic, and narcissistic. In one scene Big Edie looks longingly at her wedding portrait, years after her husband left her destitute. In another, she indulges in a predilection for showboating that had her singing along to “Tea for Two” as the record played. Little Edie seems to seethe with contempt for the situation she’s found herself in and the mother who requires so much of her.

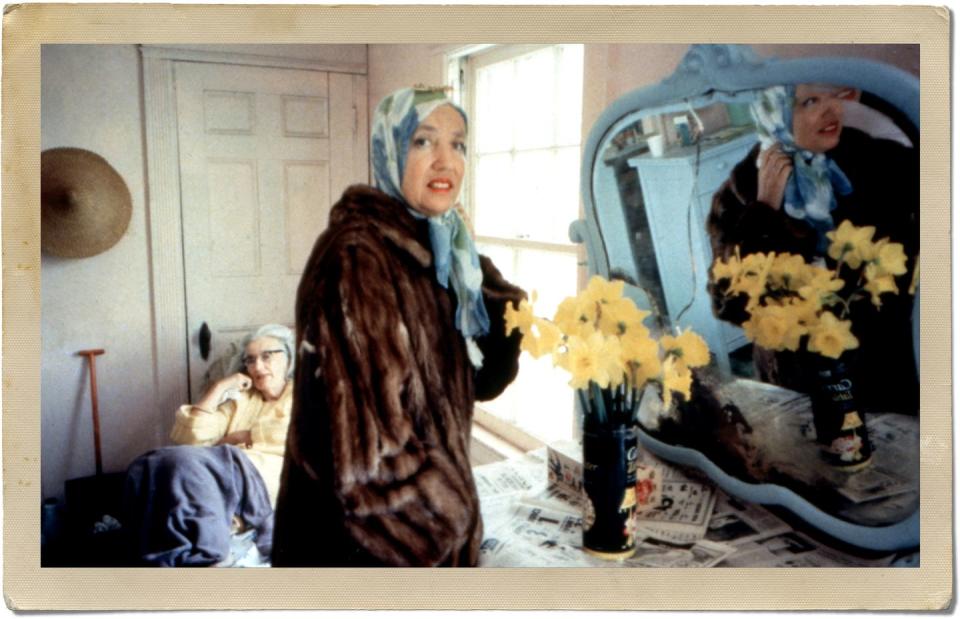

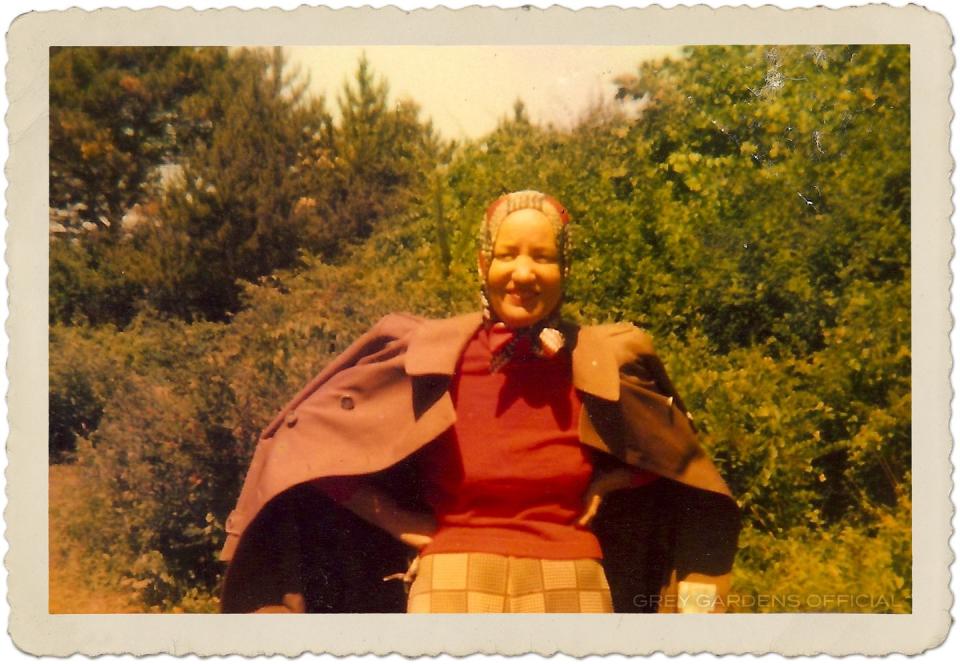

Little Edie won many fans through her sharp wit, propensity for dance routines, and a unique wardrobe consisting of turbans and cardigans worn as skirts ("the best costume for the day," as she put it). The gay community, in particular, embraced her and provided her with friends for the rest of her life. Grey Gardens was a critical success and became a documentary classic. But Pam Beale, who met Edie in 1982 when Pam married Edie's nephew Chris, believes what the film misses is just how much the Beales were suffering. “They lived in desperate poverty,” she says. “People look at the house and think, oh it's so eccentric, these old ladies with their cats. You have no idea how poor they were.”

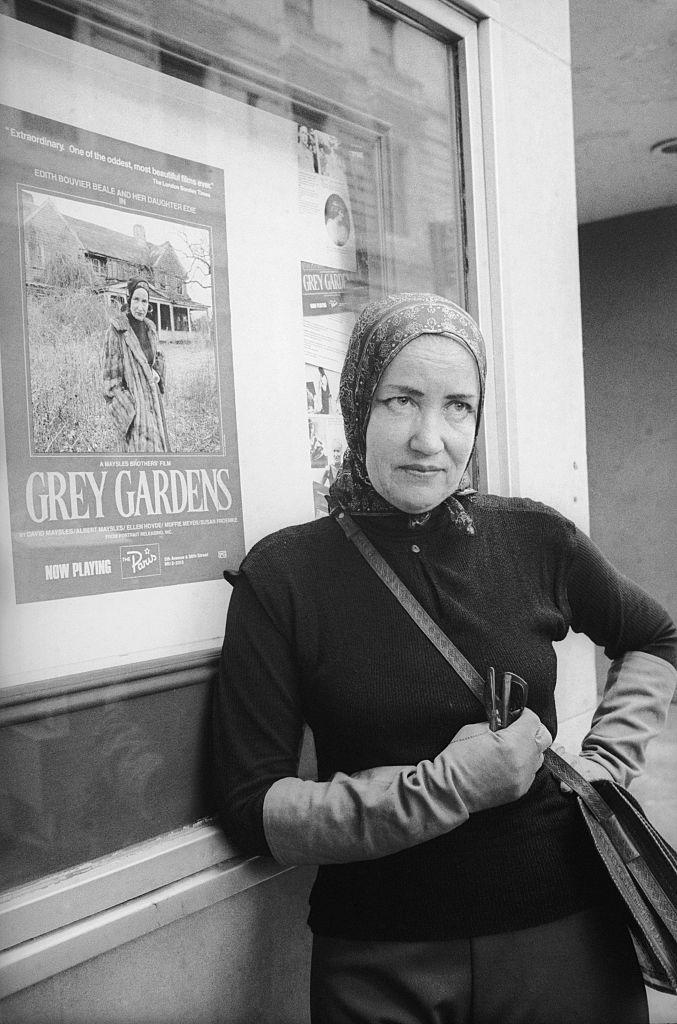

The release of the film in 1975 made Edie a celebrity of sorts and offered her the kind of opportunities she’d long dreamed for. “It gave Edie even more access to people, and as they were promoting it, she really wanted to get out there. This was her chance to become a star,” says Bartram. “The mother did not want her doing that so there was a lot of conflict in the house in the last year.”

Big Edie died in 1977. Despite their difficult relationship, Edie’s recollections of her mother turned almost immediately to hagiography. “Her mother became a saint, and so she revered her almost religiously,” says Bartram.

Little Edie spent the next two years readying Grey Gardens to sell. The location would have make it a prime property for a teardown, but she insisted on finding a buyer that would maintain the integrity of the decrepit home. The home was priced at $220,000, though Edie could have asked for far more.

“Everybody who came to look at the house would say, ‘Oh my God, this is great. We'll tear the house down, we'll get an architect, this and that.’ She'd say to the real estate agent, ‘I'm not selling it to them. They have to promise me that they won't tear it down,’” says Sally Quinn, who would purchase the home in 1979 with her husband Ben Bradlee.

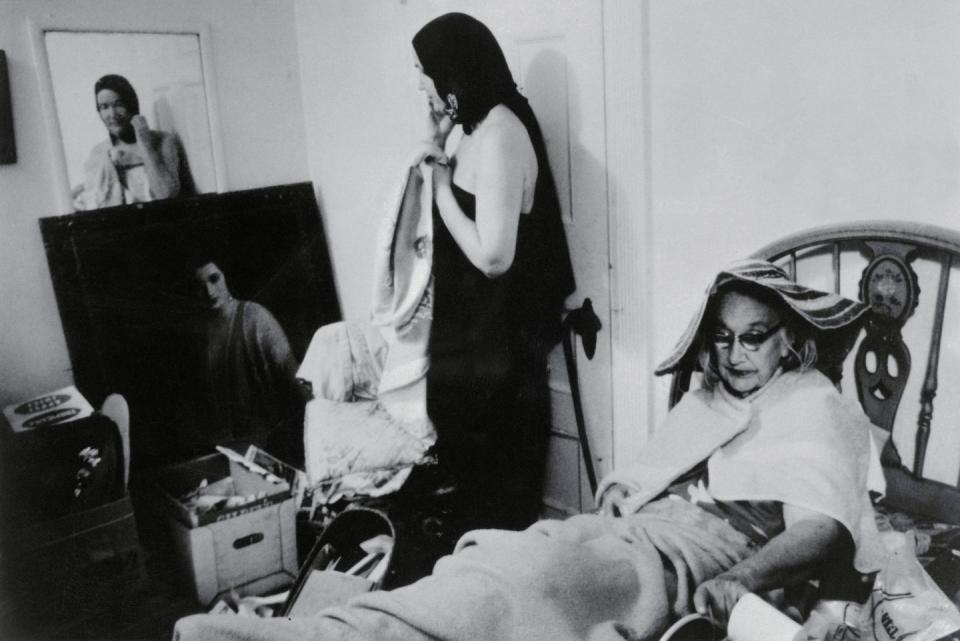

Quinn was shocked by what she saw when she first visited. “She lived in one little bedroom upstairs and she had one light bulb over a mattress on the floor and a little table that had a hot pad on it,” she says. “My real estate agent would not go into the house with me because there were so many fleas and it was horrible. I mean the smell was just grotesque. There's just no way to describe how horrible it was. I walked in the hallway and I said, ‘Oh my God, this is the most beautiful house I've ever seen.’ And Edie did this little pirouette in the middle of the hall and she said, ‘Yes, all it needs is a coat of paint,’” Quinn recalls.

Quinn’s promise that she would make only the necessary improvements to the home won her Edie’s favor. “And then she took me in and she showed me her glass menagerie with all the little animals and she showed me her mother's things. There was something so heartbreaking about her.”

After leaving the house, Edie moved into the coach house of a friend in nearby Southampton. Writer and former real estate agent Michael Braverman, who became friends with Edie at this time, saw her experience a profound reawakening at age 62. “She had been isolated there, but she wanted to get out in the world. She was very social,” he says. “I think she just clicked the switch and she was ready.”

Braverman helped shepherd her into the social scene of the Hamptons. “I remember when we served caviar at a dinner at my house, and I don't think she had it for years, if ever. She went wild. We finally kind of quietly gave her the whole tin of caviar. It was such a joy to see her having fun,” he says. “She was very welcomed by people.”

Lee Schrager, founder of the South Beach and New York City Wine and Food Festivals,met her through a friend while he was living in the area and working at Dean & DeLuca. Their friendship would continue for years. “She really preferred the company of men and boys, no question about that. She was not a woman's woman,” he says. “She was a great storyteller. One of my favorite stories that I've got was her telling me that Aristotle Onassis was going to leave Jackie for her,” he says.

The friendships she was building and rekindling at this time were instrumental in her stepping out into a new life. Susan Froemke, a Grey Gardens producer, invited Edie to a party at her Hamptons home after the death of her mother. “People were asking Edie, “What do you want to do?” And she was like, ‘I want to be a singer. I want to be a cabaret singer. This is what I'm going to be,’” Bartram says. One of the people there who worked for Maysles' films knew the people who owned and ran Reno Sweeney. He's like, ‘Oh, I might be able to connect you with them.’ He got her the interview that prompted that whole thing to happen.”

After about a year in the Southampton home, where she resided with a few cats, she was able to relocate into the city. “When her mother died and she sold the house, it was real traumatic,” says Pam Beale. “I have kept her all her writing and there's a lot in her journals and her poetry about how difficult that transition was. But it was interesting that she made the transition to Manhattan pretty well, because she had always wanted to be in New York.”

Ilene Shane was living in a friendly building on East 62nd Street and First Avenue in Manhattan when Edie moved in. “We used to hang out in the lobby and we'd see her come and go in her get ups and the turbans, dressed up to go out,” says Shane, who was at the time taking a photo class. Eventually, she asked to take Edie’s portrait and was invited into her apartment.

“All the walls were collage, pictures of cats, pictures of Kabuki. She slept on a cot. She had a huge seascape above this cot with parasols at the foot and at the head. She had shower curtains on top of the apartment’s wall-to-wall industrial carpeting. She had these plastic shower curtains with butterflies all over them and the cot looked like a beach scene,” Shane remembers. “I was like, ‘Edie, what's the story?’ So she says, ‘Oh my darling. I can't go to the beach. The men come out and haunt me so I've made my own beach.’”

Bartram remembers a woman with a lively social life. “She got back to New York and then it was party time. She was a celebrity. She went out almost every night,” he says. “She was known as good copy, and so people would ask her questions and she would say some just hysterical things.” Her antics occasionally earned a reprimand from her most famous cousin. “Jackie would come and straighten her out every so often, because she was too public,” remembered Shane. “The doorman always told me, ‘Jackie's here.’”

Twelve years her junior, Edie’s cousin was a specter throughout her life. “There was a time when she was Jackie and Lee’s highly successful older cousin, who went out with great guys and was the debutante of her year and a poet cited in the newspaper,” recalls Meyer. “Then when Jackie met Jack and became First Lady, she became the famous one of the family. I always had the feeling that Little Edie had a little bit of jealousy about that.”

Edie left New York (with, some friends hinted, a bit of encouragement from the Onassis camp) after only a few years, making her way to Ormond Beach, Florida. She had gone in search of a glamourized vision of Florida where she could indulge her love of swimming, but she found herself far from Palm Beach and in less than welcoming waters. “She was out of the limelight and she hated Ormond Beach because the water was too cold and there were sharks,” says Bartram. “John Rockefeller didn't live there any longer, and so it wasn't the town she thought it was going to be.” She soon moved on to Miami Beach.

Meyer saw a real optimism and survival instinct in these moves. “She had always talked about the beach and going to Florida and spending time in Miami,” she recalls. “And she did. I think she was sort of the opposite of a depressive. She always seemed to have a fair amount of energy, and sometimes it was spent very well and sometimes, like the rest of us, it wasn't.”

Miami was a natural fit for Edie. She lived in a series of different buildings and found plenty of places to swim. Her life developed a predictable routine. “She had this MO with people in these buildings where she lived. She would befriend the staff and she would find somebody on her floor who would take her places, grocery shopping. She continued to go to church,” says Bartram.

She reconnected with her old friend Lee Schrager, who now owned a gay bar on the beach called Torpedo. “She loved hanging out in the bar, obviously, because she was a big celebrity amongst the boys,” he says. They held several Grey Gardens nights where the movie would be screened for a crowd, followed by a performance by Edie. “It was very popular. I actually think they stopped because she told me that one of her relatives told her she couldn't do it anymore.”

Despite the familial tension—and her years of isolation—Edie was adept at keeping in touch, sending letters and making regular calls to her friends and relatives after leaving New York. “The sense I got from her letters and from the phone calls was that she was very self-sufficient, very cheerful, very Edie-like, ranting on about politics,” Meyer says. “Occasionally, she would call up and say, ‘Time to make another film!’”

During the ‘90s, Bartram says, Edie began to struggle. She became convinced that the deaths of her brothers and Jackie Onassis, which occurred over a short period of time, suggested a conspiracy. “Edie got a little paranoid about that and thought that maybe somebody was killing them all. Actually, she thought the Kennedys were doing it. So she tried to get out of the country and she decided to go to Montreal, because they spoke French and she liked cities and it was cosmopolitan,” says Pam Beale.

In Canada, her world constricted. “She lived in a high-rise apartment in a nice neighborhood, but not a walking neighborhood. It was not at all what she was used to, so she's very isolated, and unbeknownst to her, she's in the middle of the French separatist neighborhood, and so there were bombings and other things that really frightened her,” says Bartram.

As she famously confessed in Grey Gardens, “I only care about three things: the Catholic Church, swimming and dancing.” Montreal was only offering her one. “She wrote often,” says Eva Beale, the wife of Edie’s nephew Bouvier Beale, Jr., who runs a brand called Grey Gardens that's all about Little Edie's style and wrote the book Edith Bouvier Beale of Grey Gardens, A Life in Pictures. (The brand's Instagram account is a trove of all photos of Edie.) “It seemed that she was lonely while living there. The cold weather finally got to her.”

Pam and Chris Beale invited Edie to come stay with them in Oakland, California. Edie had never been to the West Coast before and so the Beales took her straight from the airport to a restaurant on Ocean Beach, where she ate clam chowder. Pam could see that age was starting to take a toll on Edie, who was then nearing 80. “She looked at the Pacific Ocean for the first time and it was just really exciting for her. But she was frail when she came down from Montreal. She was pale and very thin, a little bit unsteady and showed her age, to some degree, which I had not seen, ever, before.” Pam remembers Edie spending her days watching Turner Classic Movies and sunbathing in the yard with the family’s pugs.

Edie eventually returned to Florida, living in Bal Harbour where she could swim and see her friends, many of whom were fans turned pals. Many close to her were surprised not to hear from her around the New Year in 2002. A Los Angeles friend was concerned enough to call her apartment building “The apartment complex said, ‘we'll send somebody up,’ and that's how they found her,” Bartram says.

When Big Edie died, many doubted Edie could live without her. She survived, and found joy, for over twenty years. “You know, she wasn't angry how life ended up for her,” says Schrager. “She was a society debutante, was related to the former First Lady of the United States, from an important family and she ended up alone without much money. But she didn't complain.”

You Might Also Like