What Really Caused the Parnham House Fire

Approach Parnham House on foot and you may think you’ve stumbled upon a giant theater set. For something dark, a tragedy perhaps. The windows reveal only the cold blue winter sky; sets of chimneys stand perfectly erect in defiance of the hollow ruin within the high walls of stone. But there are no actors here, no audience. Only a crying crow breaks the silence.

Even the most stately English home will eventually succumb if abandoned long enough. But it’s clear that whatever befell this house, cradled in a verdant vale of western Dorset, it was not far in the past. You detect a recency to its demise. The geometry of the formal gardens remains, although rills that once flowed from the mouths of lion medallions are dry and partially overgrown. Proud parades of topiary yews, surely once immaculate, have gone slightly shaggy.

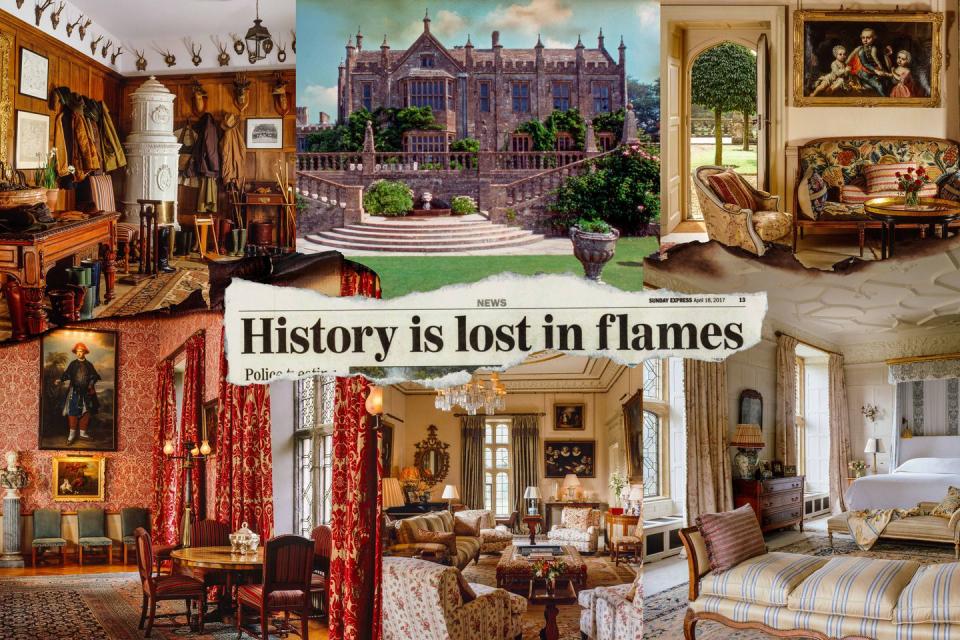

There might still be beauty but for the chainlink fence that now protects the house from gawkers, treasure hunters, and reporters. It was originally put up to protect a crime scene, because Parnham House, an architectural gem built during the reign of Elizabeth I and reconfigured by John Nash in the early 19th century, indeed has a tale of woe to tell. A tragedy with all the ingredients: a riven family, the loss of property and great wealth. And of life.

Even better, perhaps: It’s a mystery story-more Agatha than the Bard, but with no tidy denouement-beginning with a ferocious blaze, for that is what destroyed Parnham House in April last year, followed days later by an arrest. Stunningly, the man taken into custody was its owner, Michael Treichl, an Austrian-born financier of impeccable credentials and reputation. Then, two months later something worse still: His body was found floating in the waters of Lake Geneva. (Records show that he had rented a boat.)

Treichl was a man with everything: unlimited funds, the lifestyle of a prince, and a fairytale marriage to Emma Treichl, an Anglo-American former model-half Catherine Deneuve, half Robin Wright-with whom he had two children (as well as two stepchildren from her first marriage). What could have driven him so low? Had Treichl become gripped by depression, as the family has contended, or was there something else?

Theories, rumor, and gossip abound. Was this an insurance scam gone wrong meant to conceal the collapse of his finances? Was there a marital conflict that had spun out of control? Or could it yet turn out that Treichl was at Claridge’s in London on the night of the fire, as he is believed to have told the police, and someone else put the match to his home-and that his death on the lake was not suicide at all but murder?

Just so, says Robert Kime, the great British decorator who had refurbished Clarence House for Prince Charles and Camilla Parker Bowles, a decade and a half ago, when Treichl snagged him to work the same alchemy on his Dorset idyll. The project took Kime two years, during which time decorator and client became close friends. It was a conversation at Treichl’s memorial at the Brompton Oratory near the Royal Albert Hall in London last summer (with whom Kime won’t say) that convinced him that Treichl was a victim, not a perpetrator. Thugs burned the house and killed Treichl. Russian thugs, to be precise.

“I was told it, and I believe it,” Kime says. Treichl had borrowed money from these unidentified Russians and defaulted. That’s what Kime heard. “They wanted it back, and then he said, ‘Well, I’m terribly sorry, but, you know, the market’s moved, it won’t be back for a few years… I can’t pay you.’ They then burned his house down and murdered him.”

One thing we can do now with some certainty is measure the loss. Purchased by Treichl from the renowned British furniture maker and woodwork teacher John Makepeace in 2001, Parnham House under Treichl’s stewardship was, for the first time in decades, a family home, with all the rhythms of a well-to-do British household, the children at boarding school during term and home for the holidays. Kids’ birthday parties, a giant fir in the main hall at Christmastime. A cozy world all its own, Parnham had many moving parts that were oiled by the butler, with help from a housekeeper and, for a time, two cooks (one from France, the other from Dorset), who kept the flock fed. Outside, gardeners and grooms tended to the grounds and the horses.

It was a playground for grown-ups, too-for Treichl, for Emma (whose first husband was the Italian banker Stefano Marsaglia), and for whomever they invited for the weekend. The busiest time of year was pheasant season, from October to the end of January; guests often arrived in helicopters that landed in the deer park, footmen gathering their luggage and ushering them inside. Titans of finance came, as well as assorted aristocrats, faded but real, from Treichl’s native Austria and across Europe.

As hosts-and employers-the Treichls were unerringly gracious. “They were lovely,” recalled one local who assisted the staff when things got busy but who asked not to be named. “They were so polite and charming. Him particularly so.” She adored Treichl’s father, too, a regular visitor who died in 2012. “He was as lovely as you could possibly imagine.”

That’s all gone, and so, of course, is the house itself. The fire gutted its 16th-century wings. Roofs caved in, as did interior floors that bound the whole together. The exterior walls are standing now, but there’s no telling how long they will last. While it was no Blenheim Palace or Highclere Castle (which played Downton Abbey on television), it was a Grade I listed building, a designation reserved for homes of unique historical and architectural significance.

“It was a special building because of its long history,” says Brian Earl, curator of a small museum in the local market town of Beaminster (pronounced “Bemster”; this is England). A lecture he offers on Parnham House and all those who lived in it has been attracting standing room audiences of late thanks to lingering fascination with the fire and what followed. “It was the subject of conversations for a long time. It kind of dwindled, and then, when they heard about the Lake Geneva incident, it resurrected itself, and it’s still bubbling. It comes second to the weather.”

The house’s history was illustrious, mostly. Records show that there was a first dwelling built in the early 1200s by a John De Parn, who, according to Earl, was an 18th great-grandfather of Richard Nixon. But the glory years began around 1522, when Robert Strode began construction of what was to become the house destroyed last year.

Gentry if not quite aristocrats, the Strodes and their heirs remained at Parnham until 1900, after which things went to pot slightly. In the 1920s the house endured three years as a sort of country club; visitors included Arthur Conan Doyle and the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VIII. During World War II the U.S. military requisitioned it for use by General Patton as his HQ ahead of the D-Day landings. Dwight Eisenhower came one day for lunch.

In living memory Parnham served first as a home “for forgetful and confused old ladies,” in the words of Giles Wood, who grew up and still lives in a glorious stone farmhouse across the main road from the estate (he also ran Treichl’s pheasant shoot). “You’d get these old dears walking up our lane, just scuffing along and picking flowers,” he recalls. “They were quite bonkers.”

Makepeace bought the entire property for $140,000 in 1976, turning it into his home as well as a furniture-making school with a dozen or so live-in students that became world-renowned. Over the years his pupils included David Armstrong-Jones, son of Princess Margaret and Anthony Armstrong-Jones. It was 25 years before Makepeace decided to shut up shop and move on. He sold Parnham to Treichl for $5.7 million.

“It was a wonderful house, and it was a heaven-sent chapter,” Makepeace said over chocolate biscuits and tea in the smaller but still exquisite house he now occupies in Beaminster; the house is a virtual museum in its own right, stuffed with examples of his own designs and craftsmanship. “The history was just incredible, and it was idyllic. It really was.” He recalls his delight at finding not just a family to buy Parnham but one with enough money to keep it up and upgrade it. “A house like that needs a fortune spent on it every hundred years or so.”

In fact, it took $14 million. That’s what Treichl reportedly spent to transform Parnham once again. Walls were removed to make larger spaces; a new carved oak staircase was installed; a private cinema with a 16-by-nine-foot screen, a small stage for family shows, and deep sofas for about 20 people was built.

Teams of masons, carpenters, plasterers, and plumbers attended to damaged stonework, missing paneling and wainscoting, and leaking pipes. Chris Toms, a local electrician who installed an audiovisual network (something important to Treichl, who needed screens wherever he was in the house to monitor the financial markets) and who frequently returned in later years to fix glitches or replace equipment, marvels at it still, the process and the end result.

“It’s all gone now, but it was really, really beautiful,” Toms says, discussing Parnham House and its fate in a coffee shop in nearby Bridport, just inland from Dorset’s Jurassic Coast, which has the coarse pebble beaches and golden cliffs familiar to fans of the recent British TV hit Broadchurch.

He recalls the toilet in Treichl’s bathroom encased in what amounted to a sort of wooden throne, the slate and glass rainfall shower, as well as the giant tapestry that hung above the staircase. Nothing, however, seemed over-the-top to Toms, nothing overly bright or gaudy. “I’ve done work for a few other wealthy families, but, for lack of a better description, this was done tastefully-not what I’ve often seen with people with, you know, ‘new money.’”

Though there were definite Austro-Hungarian accents (coats of arms, suits of armor, and a kachelofen, a ceramic Austrian stove), Parnham was also very landed gentry British. Partly this was thanks to Kime and his choices: bedrooms in faded fabrics, stripes, and floral designs; four-poster beds for guests; rugs and runners of a certain vintage on wooden floors. In the gun room 12 pairs of perfectly worn caramel-colored riding boots on a windowsill. It was also about style of living. You never wanted for a drink, but the offerings were the classics: whiskey, gin, cognac, or sherry, perhaps-none of the mixologist pretensions of a host trying to impress on the Upper East Side or in the Hamptons.

To experience the Full Parnham, you had to be there for a shooting weekend. To the uninitiated, the rituals were perplexing. Were women guests (dubbed “fluffies” behind their backs) expected to accompany husbands or boyfriends out into the fields? Generally not. Did any woman guest ever shoot? Wood remembers only one, an American.

The requisite wardrobe, if you didn’t have it already, was available at top London hunting shops, such as Holland & Holland of Mayfair. Austrian guests took shooting fashion to a new level, enough to embarrass the well-turned-out Brits. And there was a lexicon to learn: elevenses, drives, beaters, keepers, loaders.

No two shooting days were exactly the same, but they all started with guests assembling for a full English breakfast not in the main dining room, which could seat 24 at one table, but in more modest quarters by the gun room. At nine o’clock Wood would show up with his team, a loader for each guest, to hand him his gun and keep him supplied with ammunition.

“They would toddle out all wearing the most extraordinary kit,” Wood recalls. “It was all good Euro-aristo stuff. It was fantastic. Prince this and something-something that.” Once everyone was ready, they would board Land Rovers for the first drive of the day. Beaters chased birds out of copses in the hope that they would fly in the right direction; dogs retrieved them after they were shot.

When the action was near the house, elevenses were served there; if the weather was good, in the garden. On other days guests found themselves at an inconvenient distance, sometimes as far away as Mapperton House, another stately home, owned by the 11th Earl of Sandwich, in which case, at the appointed hour, a Range Rover would roll across the fields and disgorge Parnham butlers in full regalia (charcoal trousers with thin gray pinstripes tucked into Wellington boots), as well as everything required for the occasion: sausages, pies, champagne and whiskey macs, soup and caviar. And everything to serve them with, and a collapsible table.

“It was brilliant,” Wood says. “They’d set up the table in the middle of nowhere, put a tablecloth on it, and out would come the bunsen burners to cook the sausages on. It was pretty good stuff.” Chuckling, he relates one occasion when the butlers were at work just as one of the morning’s drives got underway, and a pheasant fell from the sky and landed smack in the middle of their table settings.

What Treichl had created was a paean to a kind of British noble life that barely exists anymore, the reincarnation of an ersatz Downton Abbey, itself a fiction, which struck some, including Makepeace, as a bit absurd. “I find it really sad, because life’s too exciting for living like that. It’s fine in Disneyland, but that’s what it is.”

Certainly, it didn’t come cheap. “Imagine the cost to run a house like Parnham,” Wood notes. “I dread to think.” Folk in Beaminster, who saw the house only on the rare occasions it opened its gates (notably for the annual Eat Dorset Food Fair), knew little of the goings-on at Parnham House, their only clue the clatter of the helicopters bearing Treichl himself, his guests, or, on occasion Emma, who darted about the country to compete in polo matches.

Wood was asleep when, at around 4:15 a.m. on Holy Saturday, April 15, his son Bertie burst into his room. “Dad, Dad, wake up!” he yelled. Bertie had seen from his window something that had been spotted minutes before by a passing milkman. (In parts of Britain milk is still delivered to your doorstep before dawn.) The sky above Parnham was a deep orange glow. Just as Wood, his wife, and his son arrived at the gates to investigate, the first of the local fire trucks came racing down the road.

That they were already too late was immediately clear. “You thought, oh god, there’s no point peeing on this,” Wood recalls. “Watching a fire like that is quite extraordinary. The cracking of all the timber. The ferocity of it. Flames were coming through every single window.” Wood and his family didn’t linger, however. “We didn’t want to get caught and accused of being arsonists.”

In the first truck was Beaminster fire commander Mark Greenham. “The whole building was well alight,” he says, discussing that day in his office in the town’s modest firehouse. The butler, who slept in an adjacent cottage, had quickly confirmed that there was no one inside. Emma and the children were away, reportedly in France, the master of the house had allegedly left for London, and the rest of the staff had been given Easter weekend off. But that was the only good news.

“In 32 years it’s one of the most intense fires I’ve ever seen,” Greenham says. “There was a lot of cracking and crushing of floors.” Before long he had 20 fire trucks on the scene, brought in from far and wide. It wouldn’t be until the following Wednesday that the last hot spots were declared out and the fire officially over.

Greenham’s priorities, after establishing that there was no risk to life, were to contain the blaze and salvage property, mostly art, where he could. “We didn’t try to think about the cause. We just tried to get on with it.”

The sleuthing would be left to Sean Blizzard, lead fire investigations officer for the county of Dorset, who arrived a few hours later. He was equally dismayed. “With an old property like that, with wood paneling and voids behind…once the fire got hold, it was always destined to just rip through it,” he says. He could see that the whole 16th-century portion of the building had been largely consumed. It made hunting for proof of accidental ignition, for example something electrical, impossible.

“No investigations were carried out inside the property,” he confirms. But in any event his suspicions were swiftly aroused. “There was some evidence and information that was received early on which gave the thought that it could have been a deliberate act.” He declined to comment on reports circulating at the time that gasoline cans were found on the lawn and that horses had been let out of the stables in advance of the fire, possibly to save them from it. He did establish early on that the sprinkler system had been partially deactivated, but years before, after it turned on accidentally, causing some damage.

The first the world heard that Parnham House had been destroyed deliberately was in an April 19 Dorset police bulletin. “A 68-year-old Beaminster man has been arrested on suspicion of arson and is currently assisting police with enquiries,” it said, without more ado. That sent the town into an instant tizzy. “There was a flurry of rumors about who this 68-year-old could be,” says Earl, the museum curator. “People were naming names. The poor beggars were brought out, hassled out of their homes and all that.” It took a while for anyone to put two and two together: Treichl was 68 at the time. “It became clear that it was him, but we couldn’t work out why.”

How to fathom the news? Treichl had vowed on television to rebuild and was described as distraught by Emma, who had returned from France to be by his side. “Michael was at Parnham the following day, looking at the burning wreckage,” she said at the time. “I don’t recall his exact words. He was sobbing.” Treichl released a statement following his arrest. “I am devastated at the loss of our home. The restoration of Parnham has been my life’s work, and it is insane to think I could have destroyed it.” Police released him on bail, although he was still “under investigation.”

Treichl’s body was retrieved from Lake Geneva on June 16. His death was confirmed in a family statement that intimated suicide. “Michael Treichl sadly passed away on Friday, having suffered from severe depression,” it said. An inquest by Swiss police found no foul play. It was not until October 3 that the Dorset police issued a new bulletin that sought to put a lid on the affair

“The circumstances of his death have been investigated by the Swiss authorities, and this has now concluded,” it said. Mark Callaghan, detective chief superintendent, sought to do the same for the fire itself. “I can confirm that detectives have conducted a thorough and detailed investigation, and having assessed all the evidence collected by officers as part of this inquiry, Dorset police has concluded its investigation and is not looking for anyone else in connection with the fire at Parnham House,” he said in a statement.

Concluded but not closed, as Blizzard points out. It’s “currently a cold case,” he says, and will remain so until the police “decide to close it formally or until more evidence comes to light.” Such evidence could come, he reveals, from digging by Burgoynes, a leading forensic investigations firm in London that specializes in cases of arson; Burgoynes was hired by the company holding the insurance policy on the building. That company, a spokesperson for Burgoynes confirmed, is Chubb Limited. Chubb declined to comment.

However, the hiring of Burgoynes suggests that a claim may be pending. Blizzard notes that a claim couldn’t reasonably be filed if there were indeed evidence that Treichl had set the fire himself. “If foul play was proven on behalf of somebody involved with the property, the insurance probably wouldn’t pay,” he says. On the other hand, “if it were a third party who had come in and set the fire, then I’m sure that they would have been insured against that.”

Who that third party might have been is obvious to no one except Kime. “I just know that he didn’t do it and that he was murdered by Russians, because the fire was so complete and so enveloping that it couldn’t have been started by one man-and there were five men and they burned it simultaneously,” the designer insists. “He was a good mate and friend, and he wouldn’t have behaved like this. He wouldn’t have behaved like a criminal. They got him in the end-and murdered him. He was murdered, definitely.”

Toms, the electrician, saw both Treichls frequently and even today does occasional jobs for Emma, who was has been living in a rented house in Cheddington, a few miles north of Beaminster. He saw nothing to suggest that money had run out or that there was marital trouble.

“To be honest, if it had really been that bad, he probably would have shot her,” he says. Or they would have simply separated. That Treichl was depressed makes more sense to Toms. And he could be on Kime’s wavelength too. “I’d be more inclined to it having been a setup, like, ‘Unless you do this, we are gonna do this to your family.’ I don’t know-that’s pure speculation.”

The local woman who helped at Parnham occasionally isn’t sure the marriage was rosy. “The first thing I said was divorce,” she said of the day of Treichl’s arrest. “I didn’t know anything. I just knew that something was wrong.”

Few outsiders were closer to the family than Wood. In one photograph he points to the second-floor window of what had been Treichl’s office. Wood says he must have been in there 50 times, at least. He and his wife went to Emma’s 50th birthday celebration. His kids went to the Treichl kids’ birthday parties. “I still think it could well become a fantastic movie. I mean, it’s absolutely fantastic-these European aristocrats living the most wonderful lifestyle. She has polo teams. He’s going around the world doing whatever he does. But then he commits suicide.”

Wood doesn’t buy the rumors of financial ruin or marital strife. And when asked when it sank in with him that Treichl had torched his own house, he replies, “It never has.” Rather, he believed it when Treichl talked about bringing the house back. When Wood spoke to him by phone in the weeks between the fire and Treichl’s death, it was to plan the next season’s shooting. Treichl didn’t sound like a man planning to end his life.

With his two gun dogs mooching before a wood fire, Wood betrays a certain weariness of the Beaminster rumor mill, which never stops turning. “It doesn’t make any sense at all. You don’t know what’s going on in a family, so no one actually can say, ‘This happened, that happened, because of this, because of that.’ Everyone gets carried away. ‘Oh, she’s having an affair… Russians… Haven’t got any money… Big toe falling off.’ It’s crazy. It’s absolutely crazy.”

“All the conversation revolves around rumors, and it will forever,” he sighs. “No one will ever really know what happened. Or why it happened.”

This story appears in the June/July 2018 issue of Town & Country. Subscribe Today

You Might Also Like