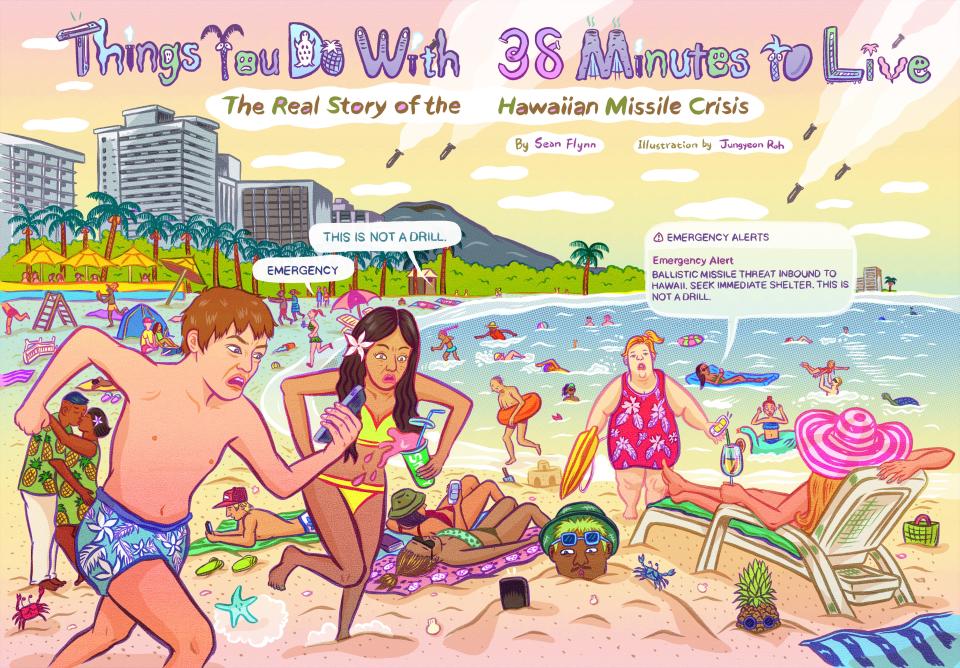

The Real Story of the Hawaiian Missile Crisis

January 13, 8:07 a.m.

Vern Miyagi has two cell phones, personal and work, and both are chirping and skittering on the table at once. This cannot be good, if only because the racket is interrupting Vern's quiet Saturday morning. He's at his house in Hawaii Kai, drinking coffee and reading the newspaper and, now, reaching for his phones.

There is a white box on both screens filled with black text. EMERGENCY ALERT is in bold letters at the top. Below that, in regular text but all in capital letters, it reads: BALLISTIC MISSILE THREAT INBOUND TO HAWAII. SEEK IMMEDIATE SHELTER. THIS IS NOT A DRILL.

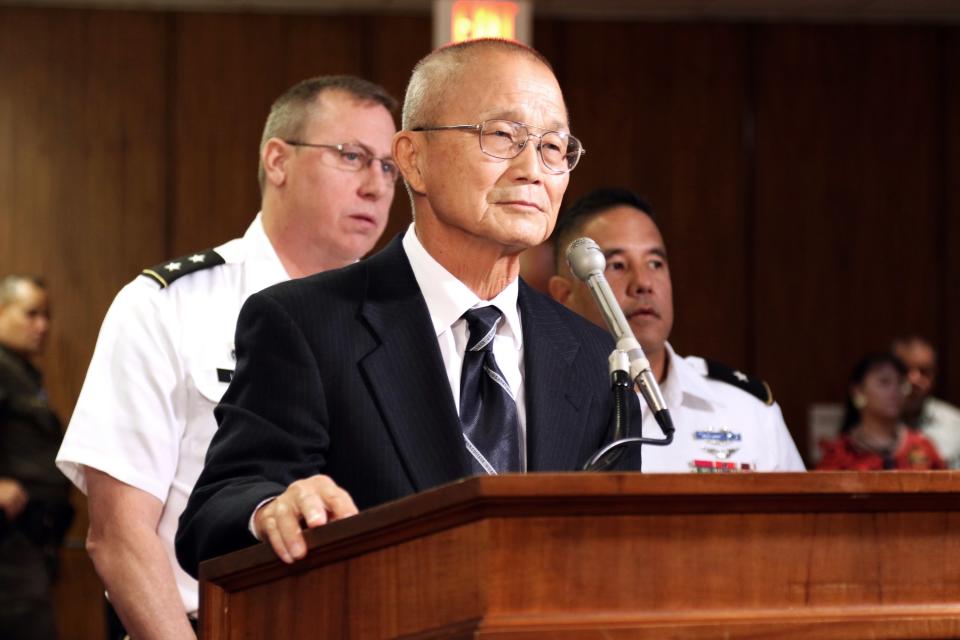

Vern is startled but not alarmed. He is the administrator of the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency, which means people who work for him sent the alert. Yet no one has called him. Nor does he hear an undulating wail from the sirens staked around Oahu, a tone his agency began testing only the month before to differentiate a missile alert from the flat squeal of a tsunami warning. His people are supposed to push the button for the sirens, too.

Vern was in the army for 37 years, retired as a major general, last posted to the Pacific Command. He can differentiate, by training and habit, realistic threats from wildly improbable ones, and he can do so quickly. The only belligerently nuclear nation is North Korea. It has missiles capable of hitting Hawaii—and the mainland—but the odds of a warhead surviving re-entry into the atmosphere aren't clear, and the targeting technology is probably primitive enough to make any attack less of a precise strike and more of a horseshoes-and-hand-grenades toss. True, Hawaii would be the most obvious target, considering it is more than 2,000 miles closer to Pyongyang than Washington, D.C., is. But lobbing a missile at Honolulu would all but guarantee Kim Jong-un's annihilation, and he has shown no recent signs of suicidal insanity. Just five days ago, in fact, Kim agreed to send athletes to the Olympics.

Vern hears footsteps behind him, his wife padding down the stairs. "Honey, honey," she says, a hint of panic in her voice. Two of their grandchildren are in the house with them. She's holding her phone so Vern can see the screen. "Is this real?"

"Let me check," Vern says. He pauses, motions toward the center of the house, the safest part, where his wife and his grandchildren should be. "But go ahead and hunker down anyway."

Chris Luan rolls over in bed, reaches for her phone. It's making an odd sound, not the normal tuch tuch of a text.

She reads the black letters in the white box, starts to read it again.

Chris rolls back the other way. Her daughter, 18 years old, is standing near the bed. She's holding her phone. Then her son, 14, is behind his sister, and he's holding his phone.

"What is this?" her daughter asks.

"I don't know," Chris says. "A missile alert, apparently."

Water. Chris grew up in California, where an earthquake or a mudslide was always waiting to wreck the place, and her father always told her to gather water if anything bad was happening.

"Go fill some jugs," she tells her daughter. "You," she says to her son, "get pillows and blankets and put them in the pantry." The pantry is in the middle of the house, no windows, might survive a blast, stocked well enough to keep them alive for a week, maybe longer.

Chris goes to the bathroom, plugs up the tub, turns on the tap. More water. She gathers all the cash in the house, identification for her and the kids. She sends the dogs out to pee.

She thinks: I've got 15 minutes.

Chris is good in an emergency, methodical, practical, believes that one creates her own circumstances. She used to be a paramedic, before she moved to a dispatcher's chair, soothing traumatized callers while she routes ambulances around the island. Her work requires her to be calm when others are not.

Shit. Work. I've got to get to work.

She believes she might die, and very soon, but her first reaction is what she's practiced. She's trained for mass-casualty events, and the first rule is to be ready to report to work.

The first rule is to leave your family. The first rule is to override instinct.

Kathleen French is holding her phone, switching Pandora stations to something she wants to listen to at the gym. The ringer is off, so there is no alert sound: A white box suddenly overrides Pandora, takes over the screen.

I'm going to die. Kathleen believes this, immediately and viscerally. Or she will survive and suffer horribly. She does not, in that moment, weigh the relative merits of either outcome.

She does not hear any sirens, which she finds odd because she always hears the tsunami warnings, even in her apartment 25 floors above the Ala Wai Canal. But is that any odder than getting tweeted into a nuclear war? She believes that has happened, too. There had been reports all last week that Donald Trump wanted to attack North Korea. There had been no threat of fire and fury, like last summer, but jabbering about a limited strike, a "bloody nose" assault, as if the nuclear-armed world was a middle-school playground.

This is what it comes to, Kathleen thinks. It's not a fully coherent thought, more of an instinctual recognition, utterly confusing yet perfectly rational. Fire and fury to bloody nose to whatever got tweeted overnight.

She's trying not to panic. Think. She has to call Jeff Judd, her husband. He's gone for a run, down along the canal, exposed. He never takes his phone. She dials his number anyway.

Three people had worked the overnight shift at the State Warning Point (SWP), which is exactly what the name suggests: the point from which warnings about bad things are sent through a statewide alert system. Physically, it's a room of monitoring equipment within the headquarters of the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency, which is a bunker dug into the side of Diamond Head Crater, and it's staffed around the clock, watching for storms and tsunamis and, because this is 2018, inbound nuclear missiles.

If North Korea did launch an ICBM toward Hawaii, the military's Pacific Command would notify the SWP, where the staff would tick through a checklist 20 steps long. War gamers and analysts consider an attack to be vanishingly unlikely, but the people in charge of issuing warnings still need to be well practiced. At the end of the overnight shift, the supervisor decided to run a drill, a pretend attack, to make sure everyone knew how to react.

The morning shift—three fresh, rested bodies—came on at 8 a.m. One of the night-shifters stepped out and at 8:06 called the secure phone in the SWP. Another worker put the call on loudspeaker, so everyone could hear the drill message. It began with "exercise, exercise, exercise," continued through a script that sounded like a real warning, then concluded with "exercise, exercise, exercise."

The staff followed the checklist. Anticipated time of impact recorded. Clock counting down to that time activated. Wailing sirens activated. Computer system ordered to send an alert to cell phones and broadcast stations. Steel doors to the bunker sealed.

All of that was simulated. No one actually pushed the siren button or sealed up the bunker.

But at 8:07, every cell phone in the SWP begins to chirp and ping and vibrate. Each has a message with black text in a white box.

The SWP has issued a live ballistic-missile alert to the entire state. There is a moment of shock, followed by controlled panic. They have to stop the alert, undo it.

Except they can't. The system doesn't work that way. It's an odd, Strangelove moment: Just as a nuclear war can't be called off once it starts, neither can the warning of one.

8:08 a.m.: 1 Minute Since Alert

Vern Miyagi calls the number for the State Warning Point. A voice answers, spits out two words—false alarm—then hangs up. Already Vern's moving toward his car. He'll drive to Diamond Head, wait in the bunker with the people who work for him who've just scared the shit out of a million civilians. He knows the alert can't be immediately undone, and he doesn't know how long it'll take to figure out how. This has never happened before.

A man is bent over a microphone. Middle-aged, balding. Andrew Canonico recognizes him: same guy who does the announcing at all the wrestling meets. He seems nervous.

"We need everyone to file into the locker rooms," the man says.

Andrew's on a wrestling mat in the Hemmeter Field House at Punahou School, waiting to weigh in, and he doesn't feel like getting up, let alone filing off anywhere. He's 15 years old, and he's been cutting weight for days, trying to make 160. He showed up this morning a half-pound over, had to run six laps to sweat out the last few ounces. He's tired and he's hungry and he'd rather stay on the mat. The weigh-in is already taking too long: Some of the boys wrestling at 106 missed the skin check for ringworm, and it's slowing everything down.

"If we're going to die, at least we're together." Jeff knows it's a cliché, but it's true, and what else is there to say?

"Now," the man with the microphone says. "Everyone into the locker rooms now."

Andrew gets up. His brother, Mason, three years older and wrestling ten pounds heavier, gets up, too. So do all the other boys, more than a hundred of them. Andrew knows the reason must be important, because no one is supposed to leave the gym until the weigh-in is complete. But the adults aren't telling them why they're moving.

Andrew starts down the stairs. He's awake now, still hungry but twitchy with adrenaline. He tells himself he is not afraid. He triages all the reasons so many schoolchildren would be ordered quickly into a sheltered space.

Fire? No, whenever there's a drill, everyone gathers outside. Why would they remain in a burning building?

He turns the corner, moves down the second flight. He is an American teenager in an American high school. There is only one other reason. It happened in Rockford, Washington, in September, and just the month before in a little New Mexico town called Aztec, and it happened at Sandy Hook and Columbine and all the other ones, too many to remember the names.

Active shooter. The adults are locking down the place.

He tells himself again he's not afraid, and maybe he even believes it, and he keeps moving toward safety.

8:13 a.m.: 6 Minutes Since Alert

The people in the bunker cancel the alert going to cell phones. This is essentially pointless: It means only that any phone that was off or out of range at 8:07 will not, from this moment on, get the warning.

The Honolulu police know it's a false alarm. The county administrators do, too. But the system isn't set up to send a second cell-phone alert saying that the first was erroneous. The software is not equipped to do so. It's the same system used to warn of hurricanes and tsunamis and the like, and to warn of other threats in other states. No one ever programmed in a "false alert" code because why would one be needed? A tornado warning mistakenly sent in Kansas is, for example, at worst a brief inconvenience. And most warnings are simply that, a heads-up that an unfortunate thing might happen.

Only in Hawaii does the list of alerts include the threat of nuclear annihilation and, with that, existential panic.

8:14 a.m.: 7 Minutes Since Alert

Wade Hargrove III has left his phone on the shelf by his bed, next to the Matchbox cars he collects with his son, Lucas. The ringer is off and he hasn't checked it all morning because he's been making breakfast, cinnamon pancakes with a touch of nutmeg. He splurged on the real maple syrup, too, even though Lucas likes the fake stuff better.

Wade lives in a midcentury condominium on the western slope of Diamond Head. He bought it after he and Daphne divorced so that Lucas would be zoned for Waikiki Elementary School. Lucas is working on a project about American symbols, and he's chosen the World Trade Center, which is a much different symbol from the one it was 20 years ago. On Monday, Wade and Lucas will walk his project down the hill to school.

They're still very close, Wade and Daphne, raising Lucas together yet apart. Lucas has baseball practice on Saturday mornings, but he left all his gear with Daphne. Wade has to call her, make arrangements to pick it up.

He goes to the bedroom, grabs his iPhone. He missed three calls from Daphne and he has a 13-second voice mail from his friend Hans. He doesn't waste time playing it, just reads the transcription. "Hey man Daphne is trying to get a hold of you and me there's a notice we got about an incoming missile and it's on the news—maybe it with yet so all right get a hold of us…"

It's mostly accurate. But there are glitches in syntax perhaps because there were glitches in Hans's words. In the recording, his voice wobbles and he swallows hard. He sounds afraid.

Hans Nielsen has been up since 5:30, more than an hour before the sun rose over the Ko'olau Mountains. He's always woken early. When he was a boy, there were chores on his family's little Wyoming ranch, horses and cows to look after; and when he was a sailor in the navy, he liked to sit on deck at dawn with coffee and a smoke, watch the sky blush over the ocean. He was on a guided-missile destroyer enforcing the no-fly zone after the first Iraq war, a few dozen Tomahawks belowdecks, some of them tipped with nuclear warheads. He never had the security clearance to know how many, though.

His girls, 7 and almost 3, were up not long after the sun. The three of them sat on the couch, the girls watching cartoons, Hans texting friends in Canada.

The alert popped up.

He had to wake his wife, Becca. He went into the bedroom, said her name, held his phone close to her face. She opened her eyes, confused, the phone blurry.

Hans never wakes her up like that, abrupt, adamant. He's only done that once, on 9/11.

She pushed Hans's hand back so she could read without her glasses on.

Becca went to the bathroom, came back. She did not think to retrieve the survival kit, which consists primarily of a transistor radio with possibly dead batteries in a Tupperware tub in the hall closet. She did not consider where best to shelter. She's a psychologist and reflexively thought in psychological terms: If this is real, she and her family were not going to survive it, and it could be real because Donald Trump is impulsive enough to spook North Korea into lobbing a missile at Hawaii. And if they were all going to die, she'd rather her children didn't do so screaming. She called them into the bedroom, piled them on the bed, and played, tickling and laughing and not saying anything about a missile.

Hans went out to the balcony. They live on the third floor, and when the rain falls in the right place at the right time, they can see the mountains rising up to meet a rainbow. He wondered, briefly, if Honolulu would look like The Day After, a television movie about a nuclear attack on a small Kansas town that 100 million people watched when it aired in 1983.

"Did you hear about the alert?" The old woman looked at him quizzically, as if he might be a loon. "There's a missile coming." Pause. "I think."

Honolulu was quiet. A commercial airliner banked out over the Pacific, and another one was coming in behind it, a white dot against the Wai'anae Range. No sirens wailed.

He turned on the local CBS affiliate. Ole Miss was a point up on Florida. A red banner stretched across the top of the screen, words scrolling right to left. The play-by-play cut out, replaced by three tones and then a man's calm voice reading the words. "A missile may impact on land or sea within minutes. This is not a drill." Those last three were in all caps.

Hans's phone rang. Daphne, panicky. She can't reach Wade. Her whole family is in Hawaii. Her parents from New York, who watched the towers come down, her mom choking on dust that pushed up to 49th Street, are with her on the 31st floor of a high-rise downtown. Her brother is on his honeymoon in Maui.

She hates that they're all there.

She's relieved that her mom and dad are with her.

She wants Lucas and Wade there, too. "Please," she tells Hans, "you've got to reach Wade."

Hans hangs up, calls Wade. He starts toward the bedroom, stops, picks up his guitar, carries it with him, sets it against the wall just outside the bedroom door. He suspects he might need it later, and he wants it to be within arm's reach of the bedroom.

He has no idea why he thinks this, and he never will. Then he goes in the bedroom, shuts the door, and plays with his girls and his wife.

8:15 a.m.: 8 Minutes Since Alert

Wade tells himself this must be a mistake. He's read the alert, but it doesn't make sense. North Korea has been a long-shot threat since the Bush years. Why now? There is no reason. It's a test, has to be, one of Kim's ICBMs that overshot Japan and is careering back to earth on a path no one can predict, and, hell, better to spook everyone with a warning just in case.

On the other hand, it is possible Oahu is going to be destroyed by a nuclear warhead, even if only by accident.

He calls Daphne, but the connection drops. That does not concern him: Cell reception in her condo is spotty. He calls back.

"I need you to bring Lucas here," Daphne says. "I want you with me."

Wade understands that as a practical matter of survival, this makes no sense, driving from Diamond Head to downtown, closer to Pearl Harbor, which probably is the intended target if, in fact, anything at all has been targeted. But maybe it'd be better. Wade's not afraid of dying, only of doing so slowly and horrifically. And if they're all going to die, shouldn't they do it together? Death, a good death, always seems to involve loved ones gathered around, doesn't it? "Deathbed" is supposed to be a comforting word.

Lucas is brushing his teeth, a ritual he does carefully, conscientiously, with a battery-powered Spider-Man brush. Getting out of the house in the morning always takes a while. Lucas needs his socks to be perfectly aligned, his heels swaddled, the seam flat across his toes.

Wade is standing in the bathroom doorway, waiting, trying not to disrupt the routine. If this is a mistake, he doesn't want to panic his son. If it's not, he doesn't want Lucas's last moments to be ones of utter terror. But the clock is ticking. Wade can feel frustration rising. He doesn't say anything, but drops his head into his hand.

Hawaii Mistaken Missile Alert

Lucas startles at that. "What's wrong, Dad?"

Wade has never lied to his son. It's one of his personal rules, to answer every question as honestly and appropriately as he can. Like that time when Lucas was in preschool and he asked, "Why does the earth never stop spinning?" Wade has no idea why the earth never stops spinning, so he improvised a child's version of the Big Bang theory. Lucas was so thrilled by how smart his dad was that for weeks after he'd ask, "Tell me the Big Bang story again. C'mon, please, tell me the Big Bang story."

Except Santa Claus. Wade lies about Santa Claus because the truth would be traumatic, and that's his other rule, not to traumatize his kid.

Those two rules, he realizes, are at the moment in direct conflict.

Wade sighs. "There's been an alert.…"

"What kind of alert?"

"Look, it's a missile warning, probably just a test, but Mom wants us to go over there, so, c'mon, let's get moving."

Lucas does not move noticeably faster.

It's about a 12-minute drive from Wade's condo to Daphne's. It's Saturday morning, so traffic probably won't be too bad. Still, Wade thinks, dying on Interstate H-1 would be a pitiful way to go. The only thing worse would be yelling at his son when the sky flashed.

8:17 a.m.: 10 Minutes Since Alert

Jeff Judd rushes into the apartment, wraps Kathleen in a hug. He's sweaty because he sprinted all the way back. For once, he'd taken his phone with him, was listening to Zero 7 on Pandora when Kathleen called, told him about the alert. He checked his phone. No alert. But Kathleen was scared, near tears. He believed her more than he believed his phone. He'd started running, then stopped. He saw an old woman with a very small dog.

Then he ran home.

Now, Jeff checks Kathleen's phone. The alert came in ten minutes ago, which means they have ten minutes left. Maybe. He has a vague memory of "20 minutes from launch to impact," a number he'd heard in a public-service announcement or a safety briefing or some such. Not that the safety briefings meant much. The protocol sent out by the university where they both teach seemed to them to come down to don't stay in your car; get out; go into a building, or just lie down in the street.

That didn't seem like much of a plan. Weren't all those cars going to clog up the streets? Traffic is horrible enough without abandoned cars littering the roads.

Kathleen is figuring out more practical measures. She's thinking calmly, deliberately, and, she believes, rationally. "If we survive the blast," she tells herself, "there will be fallout. I should wear long sleeves. And closed-toe shoes." She suspects ChapStick and eye drops will be essential.

Jeff watches the clock. He doesn't want to walk down 25 flights, but he doesn't want to be trapped in an elevator, either. They have to move, get down from a fragile, collapsible high-rise, get as low as possible. There's a parking deck on the ground floor, walled in, a door exiting to the street. It's the safest place they can think of.

"Did you hear about the alert?" The old woman looked at him quizzically, as if he might be a loon. "There's a missile coming." Pause. "I think."

Water, Jeff thinks, we'll need water. He grabs two bottles from the refrigerator, neither of them full. But between his rations and Kathleen's sensible clothing, they believe they are prepared.

No one is ever prepared.

The elevators stop in the teens. A man gets on with a surfboard and a young boy, maybe 8 years old. "Did you get the alert?" Kathleen says to the man.

He looks at her blankly. He doesn't appear to speak English, so Kathleen shows him her phone. He understands, nods, points to the boy, indicating his son had explained it to him.

The man shrugs. Kathleen says nothing, but feels a flash of anger, resentment. If everyone's going to die, he could at least be a little spooked. It seems rude not to be.

They get off on the fourth floor, decide to walk the last flights down to the parking garage at street level. There is a girl there, alone and weeping, holding her phone as if it were a wounded bird. She seems properly terrified, and that's even worse. Her mother appears from around a corner, hurries her away.

8:20 a.m.: 13 Minutes Since Alert

Punahou School has large locker rooms, so the boys have space to spread out, high school wrestlers on one side, younger boys on the other. They know there is no shooter by now: Enough kids have phones that word has gotten around about a missile streaking toward Hawaii. A few boys are crying, but as a group they are calm. There's nothing to do but wait. Some of them stand near the cage where the guy who passes out towels is eating fried rice and watching a basketball game, like it was no more or less boring than any other Saturday morning in a locker room.

Mason Canonico checks the time, does the arithmetic in his head. If the alert buzzed on cell phones at 8:07, the missile probably had been launched at least two minutes earlier, maybe three or four. The nearest active American missile-defense batteries are in California and Alaska, which he knows from research he'd done a few weeks earlier for his class European History Through Russian Eyes. It was a group project, each student studying one topic to include in a letter to Mazie Hirono, Hawaii's junior senator. Mason's contribution was a suggestion that the state prioritize missile defense because, as he understands it, interceptor missiles from Alaska would take 15 minutes to reach Hawaii, which means the actual intercepting would happen uncomfortably close to the islands.

That also means that he expects to hear some noise by now, an explosion, or at least a good, loud whoosh.

Nothing. Another minute passes.

Some kids are already saying it was a false alarm, that they'd heard it from a family friend in military intelligence or the National Guard.

Mason isn't sure he believes any of them. But he's less scared than he was, which was pretty badly when he first heard there was a missile inbound, when kids were talking about the island getting nuked.

"No," one of his friends had told him. He'd showed Mason his phone. "See, it's a ballistic missile, not a nuclear one. A ballistic missile is different."

Mason felt a little better after that.

There's no reason a high school kid, even a bright one, should know the difference between a delivery vehicle and a warhead.

Another minute ticks off. No explosions.

8:22 a.m.: 15 Minutes Since Alert

Chris Luan's phone chirps again, this time the tuch tuch of a normal text. It's her supervisor telling her not to go to work, to stay where she is.

She's relieved for a moment. Then her stomach knots.

What the fuck, she thinks. I was going to leave my kids.

That's what she'll remember most, the first thing she'll mention when she tells the story later.

Her daughter is looking at her phone. "It's a false alarm," she says.

Chris looks hard at her. "Who said that?"

A friend, her daughter says, who heard it from another friend.

"Don't you believe it," Chris says. She knows that friend, the same one who thought a lunatic was going to shoot up Waikiki on Halloween night. "Just stay together and wait."

8:27 a.m.: 20 Minutes Since Alert

Jeff and Kathleen are in the stairwell, near the door that leads out to the street. They're one flight up, sitting close to each other, Kathleen in her sensible long sleeves, staring at the door. Figuring out where to wait was an exercise in risk management. If they were too close to the door, the pressure wave of the explosion might tear it open, suck them into a firestorm. Right? That seems a reasonable interpretation of the physics of a thermonuclear blast. But if they were too far away and the building collapsed—they were pretty sure the building would collapse—they might get buried in the rubble. Kathleen's closed-toe shoes might not be sufficient to climb out, and Jeff's water, he realized, wasn't going to last until the rescuers dug them out. Where was close enough but not too close?

A maddening puzzle.

But if they stop thinking about surviving, they'll think about dying.

No, they're still thinking about dying.

Kathleen had texted her brother at 8:22. "We got an alert about a missile coming," she'd said. "I don't know what's happening. I love you so much. Thank you for being my brother."

The phones aren't working. Did it already happen? Kathleen wonders if she should open the door, if the street will look different, like in one of those movies where some guy is the last man on earth. She decides to wait on the stairs.

Twenty-one minutes now. Every second is excruciating.

"If we're going to die," Jeff says, "at least we're together."

He knows it's a cliché, but it's true, and what else is there to say?

8:30 a.m.: 23 Minutes Since Alert

Daphne Dials Wade's number. She's in the lobby, where she'd waited with her parents, close to the stairs down below street level. But she knows there is no missile coming: She saw the tweet Tulsi Gabbard, one of Hawaii's representatives in Congress, put out at 8:19: HAWAII—THIS IS A FALSE ALARM. THERE IS NO INCOMING MISSILE TO HAWAII. I HAVE CONFIRMED WITH OFFICIALS THERE IS NO INCOMING MISSILE. But Wade should have been there three minutes ago, maybe sooner if he'd stepped on the gas.

Wade answers. Daphne hears noise in the background. A car door closing. "You haven't left yet?"

"I'm trying not to traumatize our child," Wade says. "We're hurrying."

Daphne tells him it's a false alarm but to get there anyway, she wants Lucas with her. But Wade only registers the last part. He will remember the drive. He will remember what song was playing on his iPod plugged into his Ford—the Black Keys, "When the Lights Go Out." He will remember being relieved that traffic was light on the H-1, because he also will remember thinking he does not want to be vaporized on the H-1. He will remember the sense of being on a mission—get Lucas to Daphne—and that nothing else was ever more important.

But he will not remember that Daphne told him there was no missile flying toward Honolulu. He will not be able to explain that, either, except to remark that the mind and memory can be curious things.

He also will not arrive at Daphne's until 8:54.

8:32 a.m.: 25 Minutes Since Alert

There are voices in the stairwell above, doors opening, footsteps. Jeff stands, trots up a flight. There is a small knot of people standing around a man with a yellow phone pressed to his ear. He appears to be repeating what he's hearing on the phone to the people around him.

The man says: "False alarm."

Jeff wants to be certain. He moves quickly up three more steps, close to the man with the yellow phone. "False alarm?"

A short, firm nod. "False alarm."

Jeff slumps with relief, hurries back down to Kathleen. She's standing, wide-eyed, expectant. He hugs her. "False alarm," he says. "It was a false alarm."

Kathleen sobs, and he holds her tighter.

8:45 a.m.: 38 Minutes Since Alert

Hundreds of thousands of phones get another alert. "There is no missile threat or danger to the State of Hawaii," it reads. "Repeat. False Alarm."

The 15-word message seems like it had been hastily written, judging by the odd capitalization and that the word "repeat" does not, in fact, precede anything being repeated in the cell-phone version. But it took 38 minutes to send out because a template had to be designed and then coded into the system and the state thought it needed permission from the Federal Emergency Management Agency to send the message (which it didn't). And all of that happened early on a Saturday morning, when the tech people weren't at work.

The man who sent the original alert has never been publicly identified. He is referred to only as Employee 1 in a report issued by the state after an investigation into the incident. That report claims that he has "been a source of concern…for over 10 years" and that he "has confused real life events and drills on at least two separate occasions."

Employee 1 disputes all of that and told the Honolulu Star-Advertiser that he was a scapegoat for a chaotic and badly supervised drill. He says he did not hear "exercise, exercise, exercise" but that he did hear "this is not a drill"—language that, unsurprisingly, is not typically included in a drill. He maintains, in fact, that he believed a missile really was inbound. So when he opened a drop-down menu on his computer, he deliberately clicked the line for the live alert and not the line that was nearly identical except for the word "test" in it. And when a box popped up asking him to confirm his choice, he clicked yes.

It's certainly possible this was an honest mistake. But no one else present was confused.

Either way, he was fired in late January. He's appealing, and his attorney says he might sue the state, too.

No one was reported to have died that morning, not from the nuclear panic, anyway. One man started vomiting on Sandy Beach, drove himself to a clinic, and promptly went into cardiac arrest. A surgeon put four stents in his chest after that, though, so correlation isn't necessarily causation. There was security footage of students scrambling around a college quad that the cable networks seemed to play on a loop, if only because there wasn't much panic-in-the-streets imagery to be found. Everyone also knows about panicky people driving 100 miles an hour on the H-1, but they all seem to have heard it from a guy whose cousin saw it.

"But people talk about PTSD," he said. Vern was in the military for almost four decades. He knows about PTSD. "My personal view is we had 38 minutes of inconvenience."

That is not completely surprising. Every minute believing a nuclear missile is inbound is a minute spent preparing to die or to desperately survive. There is not solely, or even mostly, panic. There is slow-motion shock, and no one knows how he will react until he is forced to. Maybe he'll open that bottle of Johnnie Walker Blue he won in a raffle four years ago, toast the bill collectors who won't be calling anymore, get half-drunk before the terror is called off. Or he might sit mute in a chair at Supercuts, pretty sure he should be terrified—the man on the radio said to move away from windows, and Supercuts has huge windows—but no one else seems worried, so he sits very still and hopes the woman with the scissors by his head has steady hands. Maybe he'll try to drive far away, across the mountains, and he'll call his family to say goodbye, but they won't believe him, and when they finally do, he has to spend his last moments on earth calming his parents.

Maybe he'll be a little more patient with his son.

Maybe he'll tickle his daughters.

Maybe she'll think very, very hard about what to wear to the apocalypse, and she will laugh about it later, but in the moment it is the most important decision she will ever make.

And it is funny, in hindsight. That said, the false alarm revealed weaknesses in preparation and, in some people, instincts for how to best protect themselves. One widely circulated video, for instance, showed a man helping his child down a manhole.

"Putting kids in manholes is not a good idea," Vern Miyagi told a few dozen people six days after the fact. "The sewers are full of methane. Please, don't do that."

Vern was in the cafeteria of the Pearl City Highlands Elementary School on a Friday night in late January, ostensibly as part of a public-awareness campaign. There were handouts, including one showing the relative safety of various structures (the building techniques of the three little pigs are a reasonable guide) and rooms within them—low is better than high, interior is better than not. He ran through a slide presentation, a major point of which was to keep threats in perspective. A hurricane is exponentially more likely to wreak havoc than a North Korean nuclear attack, unless and until Kim Jong-un becomes suicidal. Andrew Canonico wasn't being irrational: A month and a day later, a student killed 17 people in his former high school in Florida. And even if Kim detonated his biggest nuke directly over Pearl Harbor, most people on Oahu, 80 or even 90 percent, would survive it. Hans and Becca, Chris Luan, Wade if he stayed put—they'd all be stumbling through the wreckage, unless they had two weeks of provisions to wait out the fallout.

Mostly, though, Vern was there to answer questions, of which many were quite hostile. "You keep saying 'human error,' " a woman in the back half-shouted at him. "I don't understand what 'human error' even means."

Vern waited her out, let her finish. "That's on me," he said.

He told me the same thing a few days later in his office in the bunker. He's a soft-spoken man, but in a way that suggests he's confident in the few things he says rather than afraid to say the wrong thing. He wouldn't give up the name of Employee 1. He admitted there are problems that need to be fixed and that it is his job to fix them. He was probably a very good general.

He seemed mildly annoyed by only one thing. That Saturday morning, he agrees, was surely terrifying for a great many people. "But people talk about PTSD," he said. Vern was in the military for almost four decades. He knows about PTSD. "My personal view," he said, "is we had 38 minutes of inconvenience."

Six days after he told me that, he resigned.

A bunch of kids decided they didn't feel much like wrestling that day, but the tournament at Punahou still went on, albeit behind schedule. Andrew made weight by a tenth of a pound at 9:15, then immediately gobbled a ham sandwich and a peanut-butter one after that. But he got bumped up to 170, drew a bye in the first round, lost the second, and his opponent was injured for the third. "So I cut weight to lose one match I didn't have to lose weight for," he said. Mason went two and one, came in third.

Chris Luan sent her kids to a baseball tournament, a fund-raiser for school, where they'd been scheduled to volunteer. She thought getting them out of the house, back to normal life as quickly as possible, was the best thing for them. She'd wait until Sunday to figure out a plan for the next emergency, decide how to keep everyone safe and together. Then she went upstairs to the bathroom. She realized she'd made a mistake, that she'd filled the tub with hot water. Her father always told her to use cold, leave the hot tank full, a big, pre-filled container of potable water. It was still warm, though, and there was no sense wasting it. She took a long soak.

Hans asked his eldest daughter if she wanted to break out the Spam she got for Christmas, Spam being an entirely appropriate gift in Hawaii. He fried it up for breakfast, and between that and playing with Mom and Dad, maybe the morning would end up a happy memory. Hans grew up surrounded by dozens of silos loaded with missiles that could destroy the planet at a time when that was not unthinkable. The reason he remembers The Day After is because he was aware, even as a boy, that he was living in the days before.

But that was a long time ago. His kids weren't growing up that way, and he believed they would never have to.

An hour after breakfast, his daughter, the 7-year-old, was packing for a sleepover. She had her backpack open, and she was stuffing it with blankets, more than she could ever reasonably need.

Hans watched her for a moment, curious, bemused. "Why are you taking those?" he finally asked.

She looked at him as if it should be perfectly obvious. "In case there's another missile alert," she said. "That's why."

Sean Flynn is a GQ correspondent.

This story originally appeared in the April 2018 issue with the title "Things You Do With 38 Minutes To Live."