The Real Story Behind the Missing Green Vault Jewels

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

The heist had been planned for months. They had run through the scenarios, studied the streets and bridges and tunnels, scouted the escape routes, purchased the burner phones, and secured the getaway cars. Most important, they had uncovered secrets about the museum. It was November 25, 2019, in Dresden, Germany. The night was dark and cold, the air carrying the musky scent of the nearby Elbe River. Three centuries earlier, Augustus the Strong had built his palace on the banks of the river and stuffed it full of jewels: mother-of-pearl goblets, gilded ostrich eggs, coconuts inlaid with gemstones, and knives of gold etched with wild boars and the heads of lions. Rooms and rooms of sapphires, emeralds, and rubies.

By 1723, Augustus, the Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, had turned part of his Dresden castle into a museum, one of the first in Europe. He named it the Green Vault. During World War II the Allies bombed it to rubble, but the state of Saxony restored it in the 1990s to look the way it did during the reign of Augustus: a towering edifice of white stone and brick that was one of the richest treasure chests on the continent.

At 4:55 a.m. the lights went out around the castle. An electrical fire at the Augustus Bridge had plunged the neighborhood into darkness, dimming the view of the security cameras inside the museum. Two hooded men in black slipped through a window on the first floor. Using flashlights, they moved quickly through the shadows of the vaulted antechambers, past mirrored walls and a dizzying array of marvels—sea snails set in silver, bowls of amber and crystal, plates of turtle shells, and a golden owl with a diamond collar. And then: jackpot. They arrived at the Chamber of Jewels.

They took axes to the reinforced glass of a display case, shattering it, and scooped up what they had come for: 4,300 diamonds, including the diamond-laden breast star of the Polish Order of the White Eagle, a sword with a hilt with nine large embedded diamonds and 770 smaller ones, diamond-studded shoe buckles and buttons worn by Augustus himself, and a 49-carat cushion-cut diamond known as the Saxon White. Only the crown jewel of the collection, the Dresden Green Diamond, was missed. Considered one of the purest diamonds ever discovered, an internally flawless 41 carats’ worth, it was reportedly worth $80 million alone. Unfortunately for the crooks, on that night it was on loan to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Nine minutes after the gang entered the museum, at 5:04 a.m., the first police officer arrived. The thieves were long gone, and so was an estimated $130 million in jewelry, one of the largest heists in European history. But as anyone who studies these things knows, stealing the loot is only half the job. In fact, you could say the real grift was yet to come.

Diamond District Secrets

When the museum’s director, Dirk Syndram, entered the Green Vault later that morning and saw the shattered glass, he felt a physical sensation bordering on pain. He had restored the Green Vault to its Baroque glory, a painstaking process that had gone on for decades. How had these criminals shown such disregard for what Germans considered a cornerstone of the national patrimony? It was as if someone had entered a temple or cathedral and desecrated the sacred.

Willi Korte understood Syndram’s emotion—for decades he had worked for museums, or people trying to find works lost from their family collections—but he felt something other than sorrow. He was intrigued. “I felt like we were dealing with an expert gang, someone who really understood art,” Korte says. Once called the Indiana Jones of the Art World, Korte has recovered stolen art by Picasso, van Gogh, and Rembrandt. His claim to fame, however, was the recovery of the Quedlinburg treasures, a trove of religious objects from the 1500s thought to be worth a quarter of a billion dollars, including splinters of wood alleged to be from Noah’s Ark and drops of milk attributed to the Virgin Mary.

As one of the few people in the world who make the recovery of blue chip art their profession, Korte was fascinated by these thieves, who seemed to be on the level of the Pink Panthers, the Serbian gang that had stolen an estimated $550 million in jewels since the early 2000s in locales from Tokyo to St.-Tropez. Perhaps, even for someone of Korte’s stature, there were lessons to glean from this latest brazen scheme. His first hypothesis was that the thieves were working for a mastermind with a knowledge of art. The second was that the jewels would never be seen again.

“There’s no way to sell something like the Saxon White on the open market, because it would be immediately recognized,” he tells me. The stolen jewels were initially estimated to be worth $1.3 billion, but the thieves would never fetch that much: A private collector or an auction house like Sotheby’s or Christie’s would demand to see paperwork establishing provenance. (Both houses declined to comment.)

Plan A for any well-informed burglar, then, would be to offer the stolen works back to the company that insured them, like asking for a ransom after a kidnapping. “The insurance company has an incentive to settle for 10, 15, even 20 percent of the value, because it saves them millions in what they’d otherwise have to pay to the museum,” Korte says. But none of the Green Vault jewels were insured; the premiums would have been too high for the museum to handle.

Korte guessed that the burglars had been paid for the heist and then passed on the jewels to a broker who belonged to the underground black market. This broker would in turn pass the jewels on to a gem cutter, who would chop them up. What had once been the Saxon White would become a dozen small stones, sold at a fraction of the big gem’s value.

Scott Selby says there are only a handful of people on earth with the expertise to cut a diamond as valuable as the Saxon White, and most work in the secure diamond district of Antwerp, Belgium. He would know. He is the author of Flawless: Inside the Largest Diamond Heist in History, which tells the story of the robbery of $108 million in diamonds from a safe in Antwerp in 2003.

“You’re not going to find someone on the black market who can cut a diamond like that,” he says. “Somebody who isn’t really good could shatter it, and then it’s worthless.”

One Keyser Soze, or Several?

The world’s best cleavers and polishers are unlikely to touch a diamond of suspect origin. “But,” Selby says, “there are a lot of people on the middle or lower rungs who are willing to do it for a fee.” And once cut into standard 1-carat or 2-carat stones, a diamond is easy to move. “Diamonds in Antwerp could trade hands easily five, six times a week. You only need one corrupt person to enter it into the legal stream and, before you know it, it’s on someone’s finger.”

At first museum officials spoke of the heist in a tone of shock. The Dresden Castle was “as secure as Fort Knox,” boasted one former museum director, with state-of-the-art security systems that were updated every few years. How could burglars get in?

But as evidence began to trickle in, that narrative became harder to accept. Surveillance cameras had captured the thieves climbing the castle’s wall at least two nights before the burglary to cut a hole in an iron grille that protected a corner window. They then taped back the piece they had perforated to make the grille seem intact. On the night of the robbery, no motion sensors were triggered when the thieves entered through the window, because they had been turned off. No guard intervened, because the guards weren’t armed and had been instructed not to do anything other than call the police. Instead, they watched the heist on a closed circuit feed in the basement, where they had gone to hide until the police arrived.

Surveillance video turned up other clues. The day before the robbery, four bearded men wearing sweatpants and sneakers had strolled through the eight rooms of the exhibit (the Chamber of Jewels is the final room), using audio guides like tourists and pausing to inspect the display case that would be smashed to bits the next evening. Something about the men tipped the police off—a hunch, perhaps, that the burglary had been the work of a gang of young thieves who were coming into some notoriety.

They had struck first in 2014, robbing a Berlin department store called KaDeWe of close to $1 million in luxury watches and jewelry. In 2017 they had pilfered a coin of solid gold that weighed 220 pounds and was worth $4.4 million called the Big Maple Leaf. They were known as the Remmos, one of four or five clans connected to organized crime in Berlin who had made their stronghold in the district of Neukölln, the city’s answer to Bushwick. The clans originated in refugee communities that had come to Berlin from Lebanon in the 1980s and ’90s, fleeing a civil war that had begun a decade earlier. Because of their immigration status they weren’t allowed to work, and many turned to crime, including prostitution, extortion, drug trafficking, and, apparently, theft.

“The younger generation feels closed off from society and that their only opportunity is crime to work their way up the hierarchy of the clan,” says Christopher Stahl, who spent years among them for the book In the Gangs of Neukölln. “They believe that pulling off a spectacular heist will improve their standing.”

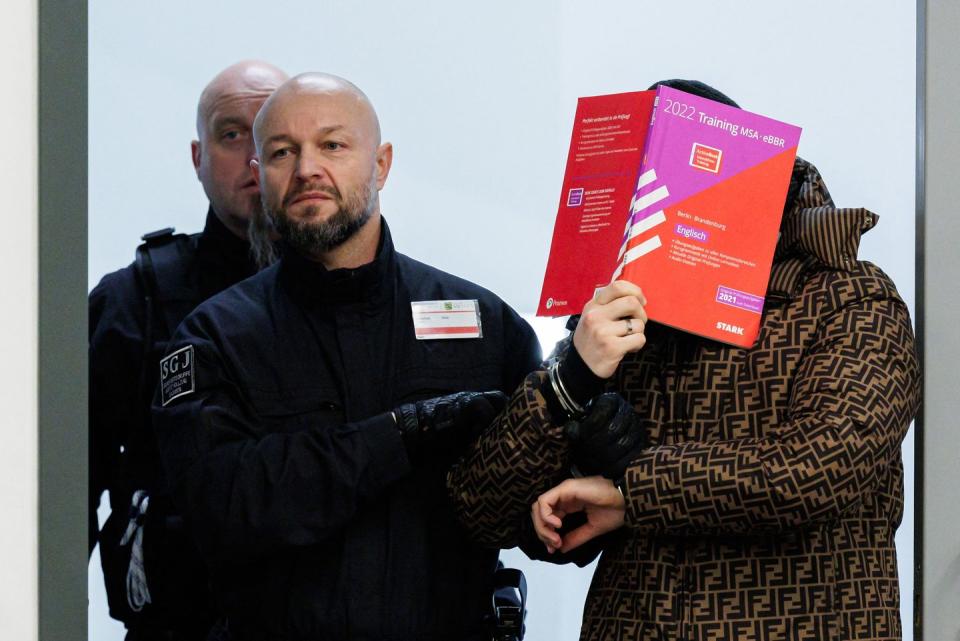

A year after the Green Vault break-in, hundreds of police officers raided shops and apartments across the district, collecting evidence that tied five Remmo men in their twenties to the charred remains of one of the getaway cars, as well as to DNA found at the crime scene. The suspected ringleader of the crew, Wissam Remmo, had already been arrested for the theft of the Big Maple Leaf (traces of gold dust matching the coin had been found on his clothing), but he and his suspected accomplices denied any involvement with the Dresden caper. The evidence in court seemed circumstantial. But then came a surprise twist. In December 2022 defense lawyers called prosecutors and proposed a shocking deal.

A Brilliant Double-Cross

On the evening of December 16, 2022, members of the Epaulettes, the elite police crew tasked with tracking down the Green Vault jewels, arrived in a tony neighborhood of luxury department stores and museums in Berlin. They had been summoned to the office of Kai Kempgens, one of Germany’s most highly sought-after criminal defense attorneys. He represented Rabieh Remmo, who was ready to confess. Kempgens led the officers into a conference room, where 31 pieces of jewelry sat on a long table. They had come from the Green Vault, and more could be found in a shipping canal that runs through Neukölln. Kempgens proposed a deal: The Remmos would return the goods and tell all; in exchange, the state of Saxony would recommend to the judge less time in prison. Prosecutors agreed, and Syndram and others associated with the museum said they were overjoyed by what was returned; the recovery was a “Christmas miracle.”

Once the 31 pieces were photographed, bagged, carefully boxed, and returned to Dresden for forensic examination, relief turned to disappointment. The pieces had been stolen from the Green Vault, but they were in terrible shape, some visibly warped. Diamonds on the hilt of the stolen sword had been damaged by moisture and condensation; they appeared cloudy and grayish in color, leading museum officials to believe the sword had been submerged in water. There was also a sticky white substance on many of the diamonds, perhaps an attempt to erase fingerprints, as well as the stench of a cleaning agent.

On December 25 divers began searching the canal in Neukölln where Rabieh Remmo said the gang had dumped the sword. They couldn’t use metal detectors because of all the scrap metal dumped in the canal, so they crawled along the bottom, millimeter by millimeter. They returned the next day, but other than a few rusty bicycles, they found nothing. What’s more, the thieves hadn’t returned the most valuable pieces from the collection. And in court, the confessions the suspects offered were contradictory, evasive, and piecemeal, a violation of the agreement, which stipulated that they reveal how they had planned and organized the crime, the exact sort of information Korte and other experts in international art theft sought.

As the trial reached its conclusion, prosecutors complained again and again that the Remmos weren’t complying with the deal they had struck. But German law governing plea bargains foiled them; the settlement was binding, and they couldn’t back out. The Remmo defense team had apparently pulled off a brilliant double-cross by milking a loophole in the law. When the five men were finally convicted, on May 16, their sentences called for just four to six years in prison. The greater deception, it turned out, seems to have taken place in the courtroom.

“They were able to exploit competing interests,” says Selby, the author of Flawless, of the defense attorneys. “Because of the cultural value of these jewels, Saxony was desperate to get them back, so they made a deal with the proverbial devil, which could set a troubling precedent. Criminals are now aware that if they steal something of real cultural value in Germany, even though it could be very hard to move, if they stash it, someday it could help them leverage a deal.”

The showpieces of the collection—the Saxon White and Queen Amalie Augusta’s diamond necklace and bow-shaped brooch, studded with 660 diamonds—remain unaccounted for. When it was discovered in the fabled Golconda mines in India, the Saxon White was considered of the “finest water,” an old term of art to describe absolutely colorless diamonds with a perfectly formed crystal structure and no impurities; only one or two percent of naturally occurring diamonds are as pure. The diamond has a D-color, the highest rating on the GIA color grading scale, the industry standard.

At the time of the theft, Marion Ackermann, Dresden’s state art collections director, said the true value of the jewels couldn’t be measured. “We cannot give a value, because it is impossible to sell,” she told reporters. “The material value doesn’t reflect the historic meaning.” But Tobias Kormind, managing director of Europe’s largest online diamond jewelry retailer, 77 Diamonds, says the Saxon White could be worth as much as $12 million.

“You’re not going to get that value without its provenance,” Selby says. “But from the perspective of a thief it’s still great, because your cost is basically just putting together a team, planning it, and whatever value you place on the risk of getting caught and going to prison. Maybe it’s a collection worth $1 billion at an auction house, and if you cut it down into pieces it’s worth $100 million, $50 million, $20 million. That’s still a really good return for what might be two or three weeks’ worth of work for the heist itself.”

The trial exposed that the Green Vault wasn’t highly secured at all; because of budget pressures, neither are many other museums in Europe. It also highlighted how comically inept the German judicial system is in dealing with jewel thieves. After all, Wissam Remmo was awaiting trial for stealing the Big Maple Leaf when he led the Green Vault crew. (Prosecutors declined comment, and defense attorneys could not be reached for comment.)

“They didn’t give a damn about the objects as works of art or historical significance,” Korte says. “They were interested in the material value.” Korte says inside sources have told him the smaller diamonds would need to be recut in a modern style, and that when the thieves discovered this, they likely adjusted their plans. They could no longer sell the small diamonds piece by piece. They would have to sell them by the pound for much less. “That’s when I think they may have said, ‘Maybe we keep some of these smaller pieces as a sort of get-out-of-jail-free card and focus on the big stones,’ ” he adds. “That’s where they could still make some money for this whole thing to be worthwhile.”

Korte doubts the police have caught what he calls “the head of the snake,” the mastermind he assumes not only planned the heist but made arrangements to sell the jewels. For those arrested, the short sentences will serve as little deterrent. In fact, Stahl, the author of In the Gangs of Neukölln, says prison is a badge of honor for young men in the clan, and if history is any guide, Wissam and his accomplices are likely to strike again.

“The museum and law enforcement seem so proud of how this case was resolved, but they really got only trinkets back. The big pieces weren’t returned, and there are no answers as to where they are,” Korte says. “If those were sold, or are still out there, and these men are doing such short time, it’s hard not to look at this and conclude that crime pays.”

Lead image: The whereabouts of the Dresden Castle collection’s showpieces, including a bow-shaped brooch worn by Queen Amalie Augusta (top row, third from left) and the epaulet featuring the $12 million Saxon White diamond (middle row, far right), remain a mystery.

This story appears in the September 2023 issue of Town & Country under the headline Now You See Them, Now You Don't. SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like