The Real Story Behind Hearst Tower

If a building is a drama, this one has three acts. The first is about mighty architectural ambitions, expressed with a combination of joie de vivre and an almost explosive bombast. The second is quieter, as difficult circumstances prevent the completion of the structure, but the portion that does get built endures for almost three quarters of a century as a beloved eccentric. And then, in the third act, the ambitions make a triumphant return, this time by reinventing the building in the altogether different form of one of the 21st century’s first important skyscrapers.

That is the saga of T&C’s home, the Hearst Tower, born in 1927 as the International Magazine Building, when it was designed by the Viennese expatriate Joseph Urban as the headquarters for William Randolph Hearst’s growing empire of magazines. Urban was primarily known as a theatrical designer, but he created several of New York’s most memorable buildings, including the voluptuous Ziegfeld Theatre in midtown. He could embrace any style and intensify what emotion there was to be found in it, which made him the ideal architect for Hearst, who had long been inclined to express his aspirations in structural form and who wanted this new building to make clear to everyone in the media capital of the world that he was not a piker from California but the nation’s most powerful media titan, with a headquarters to prove it.

Urban, working in tandem with the architectural firm of George B. Post and Sons, came up with a plan for a six-story limestone structure the façade of which would be adorned with 12 enormous sculpted figures and monumental fluted columns that stretched higher than the building itself. It had an air of amiable grandiosity, a zany palazzo more than a corporate HQ. It was conceived as the base for a tower, which the Post firm designed some years later (Urban died in 1933). But the project never went ahead, because Hearst had overexpanded—though not before acquiring T&C, in 1925. The Great Depression also put an end to Hearst’s dream to be at the center of a whole cultural conglomeration around Columbus Circle, with a new, Urban-designed home for the Metropolitan Opera next door.

Instead, Urban’s little building remained, a podium without the tower intended to go atop it, until it was decided in the late 1990s that it was time to build again, to accommodate the Hearst Corporation’s sprawling operations. This time the only way to go was up.

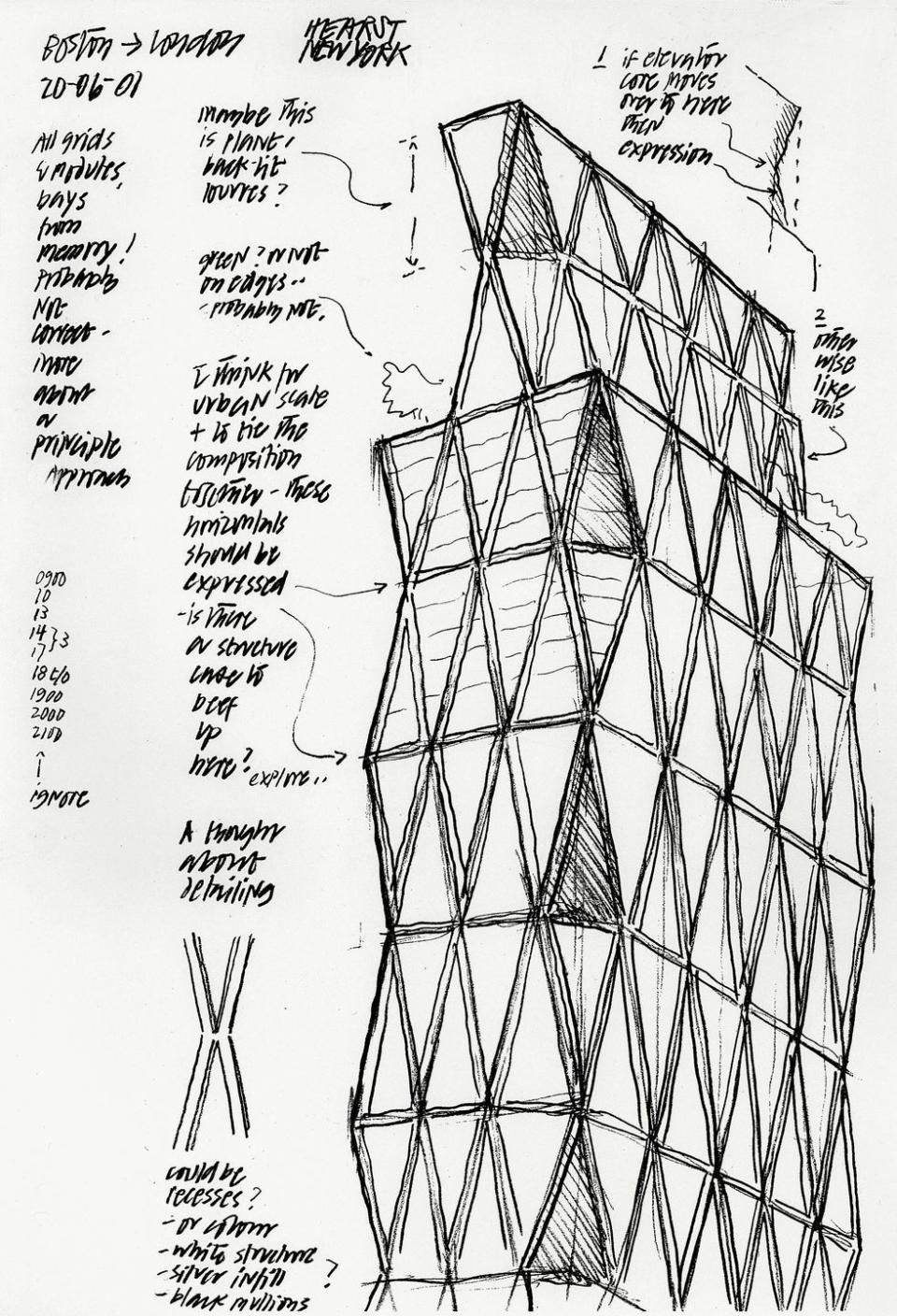

Foster + Partners, an architectural firm based in London that had produced some of the world’s most innovative and elegant skyscrapers, came onboard and proposed a sleek, refined 40-story tower of glass and steel rising above the limestone base. The design met Urban’s flamboyance with a modernist theatricality of its own: a diagonal grid of supporting trusses, covering the façade with a series of four-story triangles that slant in and out as the tower rises, like a shimmering stack of martini glasses. The first employees moved in in the summer of 2006, followed shortly by the archives of America’s oldest general interest magazine, 175 years and counting. It is from there that T&C’s editors will write its next century, even if the issue in your hands now was mostly orchestrated remotely, with a hopeful eye toward a 27th-floor homecoming.

Hearst is that rare glass tower that can be called jubilant, but then again, Urban’s base is nothing if not a burst of emotion. He brought exuberance to the streetscape, just as, decades later, Foster brought it to the skyline, and together they make a masterpiece stretching through time.

This story appears in the October 2021 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like