The Real Story Behind How C.S. Lewis Helped J. R. R. Tolkien Shape The Lord of the Rings

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

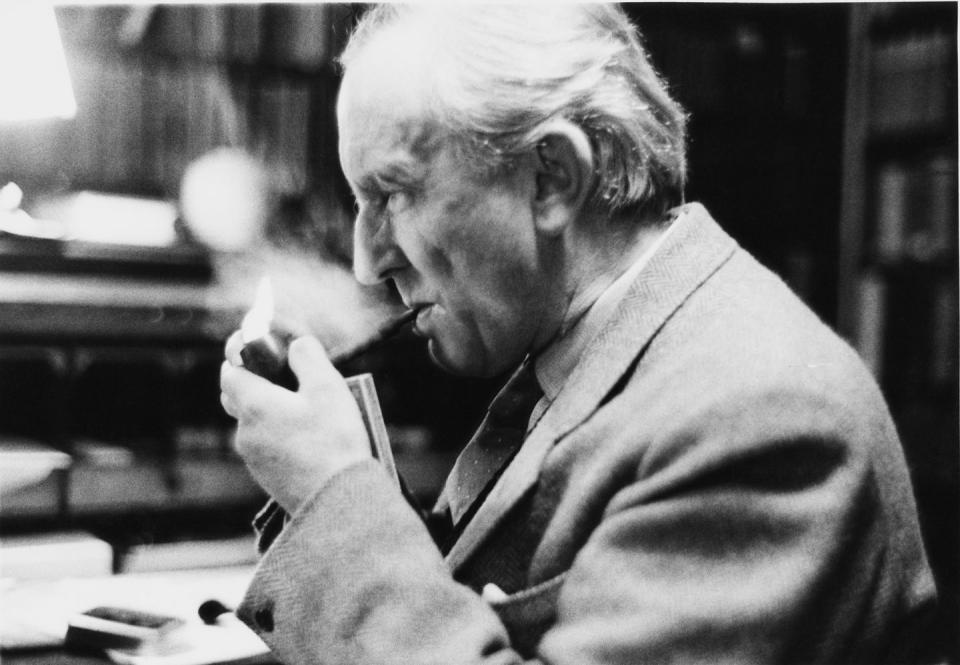

Frodo Baggins quickly discovers that heading to Mordor alone in The Lord of the Rings trilogy is not an option. Similarly, while writing can be considered a solitary vocation, J.R.R. Tolkien’s legendary trilogy was ushered into the world with encouragement from a support network that also favored the familiarity of a local tavern fit for a hobbit—or in this case, a pub in Oxford.

Literary societies are a fellowship of sorts. The 20th century gave rise to several influential groups, such as the bohemian Bloomsbury Group, which boasted Virginia Woolf and E.M. Forster, and the Stratford-on-Odéon set in Paris (think Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Joyce). Tolkien was part of the Inklings, alongside Oxford tutor and friend C. S. Lewis, and it is impossible to overstate how much this relationship impacted the shape of fantasy literature. Not only have adventures in Middle-earth and Narnia been read across the globe for decades, but these books' film and TV adaptations continue to be beloved.

Now entering the adaptation chat is the highly anticipated Prime Video prequel, The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power. Rather than simply rehashing everything Peter Jackson’s revered movie trilogy showcased, The Rings of Power goes deep into Tolkien’s Middle-earth materials— beyond the three books released in the mid-50s. The journey from writing The Hobbit to charting Frodo’s ring-fueled burden spread over three decades, and Tolkien’s path to success is not without procrastination and doubt.

“It is no exaggeration to say that Lewis would become the chief midwife” to The Lord of the Rings, writes Lewis’s biographer Alister McGrath in A Life. After all, even the most prolific and famous authors need a Samwise Gamgee to help carry them up a mountain. Here, Town & Country looks back at how Lewis encouraged his friend that writing was more than a “private hobby” and helped Tolkien when he became bogged down in devising the invented languages rather than moving the story forward.” Plus, a detailed account of the complicated years that followed success and the people who came between the two titans.

A meeting of minds

The decade following WWI was full of artistic shifts from the hedonistic Bright Young Things to the new generation of writers shaping the culture—and it wasn’t necessary to head to London, New York, or Paris to find intellectual stimulation, as Oxford University remained a literary bastion. Tolkien and Lewis had fought in WWI before returning to the prestigious academic institution. Still, surviving trench warfare was not the only link that would bind them, as they were to discover when they first met in 1926 at a Merton College faculty meeting.

English Tea is what these academic gatherings were typically called (we can’t guarantee finger sandwiches and scones were on the menu), and the pair duked it out over what should be on the Oxford English curriculum. Tolkien believed students should focus on Old and Middle English texts, while Lewis thought English Literature post-Geoffrey Chaucer was preferable. They were both in agreement that anything published after 1832 had no place being taught—congratulations Austen and Shelley, commiserations Brontë and Dickens.

Despite disagreeing with Tolkien’s position on the curriculum, Lewis joined Tolkien’s study group called Kolbítar (the name is from Icelandic and means “coal-biters”) that focused on Old Norse. Their friendship bloomed, as did Lewis’s interest in myths that spilled over into theology. Conversations with practicing Catholic Tolkien are credited with Lewis changing from an atheist position to reconnecting with Christianity in 1931—Lewis opted for the Church of England. “The story of Christ is simply a true myth: a myth working on us in the same way as the others, but with the tremendous difference that it really happened,” Lewis wrote in a letter to a friend this same year. Faith and fantasy would be a binding force that led to an informal club that would change everything for both men.

The Inklings

The Old Norse study group is the foundation of this friendship, but a different venture, a literary discussion group by the name of the Inklings would have a broader impact. Before the Inklings took up residency in Oxford’s The Eagle and Child pub, the first iteration of the group was founded by undergraduate Edward Tangye Lean (brother of Lawrence of Arabia director David Lean). “At each meeting, members should read aloud unpublished compositions. These were supposed to be open to immediate criticisms,” wrote Tolkien in a 1967 letter.

Initially, gatherings took place in Lean’s dorm room, and while this version of the literary club faded—as is the way of these undertakings—the name stuck when Tolkien and Lewis embarked on their next group hang. It would be a shame to let a good pun go to waste, with Tolkien explaining the double meaning as: “people with vague or half-formed intimations and ideas plus those who dabble in ink.” Later, the organization would take a more robust shape under the watchful eye of Lewis and Tolkien. Tolkien credits his friend’s “passion for hearing things read aloud” that resurrected the group. There were no hazing, initiations, or blood oaths to perform; writing and faith were only the entry requirements of sorts. (Though it should be noted that women did not have a role to play in these gatherings, which is sadly not all that surprising considering it wasn’t until 1920 that Oxford first awarded degrees to women.)

In the mid-1930s, if you ventured to The Eagle and Child (also nicknamed the “Bird and Baby”) on a Tuesday lunchtime, you would find this group enjoying a midday pint. Or, perhaps they were at the Rabbit Room, a private lounge area. But, for the real meat and bones of the literary criticism, you had to head to the exclusive scene in Lewis’s Magdalen College rooms after dinner on Thursday nights. Here, members read their work to each other, and the two future best-sellers were the focus. “The Inklings were a system of male planets orbiting its two suns, Lewis and Tolkien,” writes Lewis biographer McGrath about its starry duo.

The Inklings would run through WWII, and the slow decline began in the following years before eventually fading when relationships and priorities shifted. Keeping up a regular book club is difficult, let alone one with a critical function that helped bring The Lord of the Rings into the world. While no one else hit this stratospheric height, other members included multi-hyphenate Charles Williams (and later wedge between Lewis and Tolkien), and Tolkien’s son Christopher. Prolific writers like W.H. Auden, T.S. Eliot, and Dorothy L. Sayers are sometimes mistakenly referred to as Inklings but were only a friend of the group—to borrow a Real Housewives term.

A Lord of the Rings cheerleader

“But for his interest and unceasing eagerness for more, I should never have brought The L. of the R. to a conclusion,” Tolkien told Rayner Unwin in 1965 (two years after Lewis died). This “unpayable debt” is one Tolkien never forgot, and as his popularity grew in the United States in the ‘60s and ‘70s, his fellow Inkling received newfound (posthumous) attention. In some ways, this debt has been repaid, but it is clear that Lewis was a source of great support at a time when Tolkien was stalling.

“He was a man of immense creativity who nevertheless needed someone to affirm him in what he was writing—and, more important, persuade him to finish it,” explains McGrath about Lewis’s friend. Not only was Tolkien pulling double duty juggling his academic duties with his family, but his perfectionism meant he spent more time on the invented languages and world-building rather than on plot and prose. Parallels to George R.R. Martin’s as yet unfinished Game of Thrones are impossible to ignore, and perhaps Martin needs his very own C.S. Lewis to guide him back to Westeros.

In 1939, McGrath describes how Lewis made the dangerous nighttime journey to his friends’ house during a wartime blackout to drink gin and lime juice and discuss Tolkien's “new Hobbit” book. By 1944 Tolkein had hit another creative impasse, but through encouragement from Lewis, he returned to writing, and read the last two chapters from The Two Towers during an Inklings meeting. “He approved with unusual fervor, and was actually affected to tears by the last chapter, so it seems to be keeping up,” Tolkien wrote to his son Christopher, who played a significant role as editor of the later releases. It would be another decade until The Fellowship of the Ring hit bookshops, but it is hard to shake the image of Lewis as the Sam to Tolkien’s Frodo.

The Friendship Cools

Despite their close personal and creative ties, not all best friends are forever, and several people and events contributed to the widening gulf between the two men. Tolkien’s productivity points toward relatable procrastination, whereas Lewis was prolific between 1948 and 1951 when he wrote five of the seven Chronicles of Narnia. Yes, they are far shorter in length and lack layered world-building, but it is an impressive creative output. Lewis didn’t present his Narnia stories to the group for discussion, which is probably good because Tolkien was skeptical of their depth. McGrath also notes that Tolkien thought Father Christmas “didn’t really belong” in this world and “suspected that Lewis had borrowed some of his own ideas and had woven them into the Narnia Chronicles without due acknowledgment.”

Work aside, the distance between the duo began when the already published Charles Williams joined the Inklings in 1939. It isn’t only teen dramas that feature a shift after a new figure draws attention from one half of the original duo. Williams’s arrival changed the group dynamic and became a wedge between the two as Williams replaced Tolkien in Lewis’s best friend spot—yes, even literary men have friendship challenges and petty grudges. Williams died the week after WWII ended, but Lewis and Tolkien never returned to their pre-war tight bond.

Faith initially bound them, but Lewis’s more relaxed attitude toward marriage didn’t sit well with Tolkien and his Catholic faith. It is no wonder that Lewis did not tell him that he was marrying divorcée Joy Davidman in 1956, and this lack of confidence speaks volumes. It is a shame the Tolkiens weren’t included in the celebration, as this invitation shows how hard they could go at a celebratory bash. “We were separated first by the sudden apparition of Charles Williams and then by his marriage. Of which he never even told me; I learned of it long after the event,” Tolkien wrote to his son in 1963. Wounds that cut deep point to the damage done in the previous decades, but when Lewis fell ill, Tolkien visited his old friend and collaborator in hospital and at home. Lewis and Aldous Huxley died the day President Kennedy was assassinated, the latter unsurprisingly taking the lion's share of the headlines.

After Lewis’s death, Tolkien credited his friend as the man who “was for so long my only audience.” Lewis helped him see the trees (or Ents) through the weeds, and in doing so, readers—and now viewers—still get to experience the intricate world of Middle-earth.

You Might Also Like