Read About the Mystery Behind an Iconic Scarf Painted by Sargent

The great American painter John Singer Sargent, with his tremendous sensitivity to style, had found the perfect element for his art. It was a large cashmere shawl from India, cream-colored with an oversize paisley pattern in muted browns and grays, that was elegant, poetic, and very exotic. Sargent asked his niece Rose-Marie Ormond to pose for a series of works enveloped in the scarf. In his 1911 watercolor The Cashmere Shawl, now at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Rose-Marie stands in a pale taffeta gown with a lilac head scarf, the cashmere wrapped around her waist and draped over her full-length skirt.

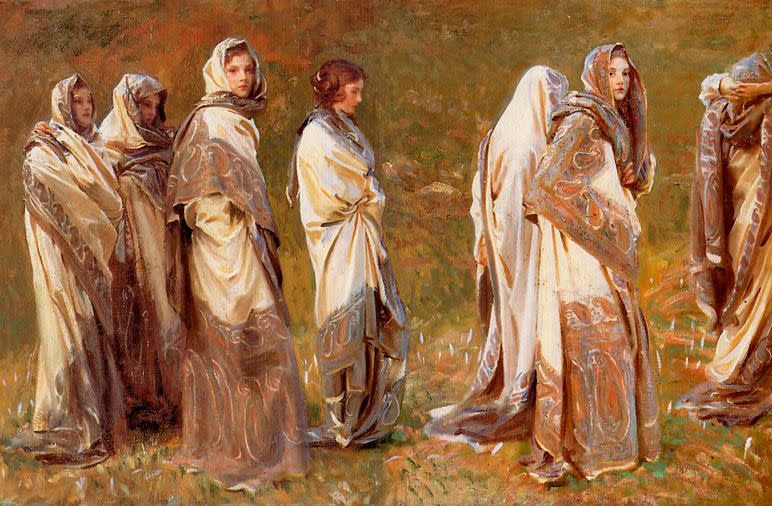

For Two Girls in White Dresses, 1909–11, a painting in the collection of the English country manor Houghton Hall, Sargent imagined mirrored images of his niece reclining in an Impressionistic swirl of ivory taffeta and paisley, while in Nonchaloir (Repose), 1911, at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., she sinks back into a sofa, the paisley pattern reproduced in the rich green upholstery. But the most spectacular Sargent painting to make use of the design is Cashmere, circa 1908, where seven different versions of Rose-Marie’s younger sister Reine extend across the canvas wrapped and draped in the shawl (in December 1996 at Sotheby’s in New York, Cashmere sold to a private collector for a then-record-breaking $11.1 million).

Decades after he painted them, Sargent’s dramatic representations captured the imagination of his great-niece, English textile authority Jenny Housego, whose grandmother, Violet Sargent Ormond, was the artist’s sister. A former curator at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, Housego moved to New Delhi in 1989, devoting herself to the creation of luxurious handmade textiles. The more she studied her great-uncle’s masterworks, the more she realized that the shawls in his paintings were all the same. “It looks like a procession, but it is in fact just one girl, my aunt, with the same shawl in different poses,” observes Housego, who recently published her autobiography, A Woven Life.

As a textile expert, she became fascinated with Sargent’s famous shawl. Her quest to give the scarf new life—and return it to her family—is a saga involving multiple generations of important families, including the Rothschilds and Sassoons; one of the great historic homes in England, the 18th-century Houghton Hall in Norfolk; a leading American art dealer, Warren Adelson; and the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

Housego’s family has remained closely connected to their ancestor. Her brother, Richard Louis Ormond, an art historian and former deputy director of the National Portrait Gallery, is a leading Sargent expert, authoring the artist’s catalogue raisonné (nine volumes, over 3,100 pages, including all of Sargent’s portraits and landscapes). “He died long before I was born, so, sadly, I never knew him,” Housego says of her great-uncle. “But elder members of my family remember holidays with him in the Alps and how he was always painting with his two sisters, Emily and my grandmother, Violet, who was the mother of his muse, my aunt Rose-Marie.”

In India, Housego devoted herself to creating businesses that support traditional handweaving methods. She cofounded Kashmir Loom, a line of cashmere scarves and throws made by the finest artisans in and around Srinagar, the lake-filled region high in the mountains of Kashmir. As a maker of sumptuous textiles, it was only natural that Housego would be inspired to conjure the wrap in her great-uncle’s paintings. “It sparked the idea of re-creating Sargent’s shawl in Kashmir,” she says of the project, which has required more than a decade of dedication. Eventually, she was able to weave eight replicas of the Sargent shawl.

Far from a superficial flourish, the scarf was an essential element in Sargent’s work. “He used fashion and decor to give an artistic and art-historical heritage to his work,” says Erica Hirshler, interim chair of Art of the Americas at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, which has more than 60 works by Sargent and an extensive archive.

On his annual summer holidays, Sargent traveled with costumes and accessories that he would incorporate into his paintings, says Stephanie Herdrich, assistant curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and an expert on the artist. “He always loved to dress those who posed for him and excelled at representing the surfaces and textures of luscious textiles,” she says. “The cashmere shawl was a favorite from about 1907. It becomes a vehicle for Sargent’s exploration of form, line, and pattern.”

But as Housego discovered, Sargent’s painting technique was far from literal. “He does not seem to change things, but he leaves out detail,” Hirshler says. “It is his view of the object. Sargent gives you the impression of a pattern without using a tiny brush to capture every dot, and he arranges them differently. He is not giving you a design that you can use to make your own shawl.” So when Housego set out to re-create the piece, one of her first goals was to see the original, or one of them. (It has been speculated that the artist had more than one.)

In the same years that Sargent was wrapping Rose-Marie Ormond in cashmere, he was close with two major English patrons and collectors, Philip Sassoon and his sister, Sybil. The siblings were born to Sir Edward Albert Sassoon and Aline Caroline de Rothschild, of the French branch of the famous family. Interestingly, on their father’s side, there are some important connections to India: Their great-grandfather, David Sassoon, founded a large banking and mercantile business in Bombay, now Mumbai, in the mid-19th century. Philip and Sybil were passionate about the arts. “Both were very involved in artistic circles in England and in Paris in the early 20th century and overlapped a lot with Sargent’s world,” Hirshler says. “They were interested in music, not just the visual arts.”

Sybil, a Jew, married George Cholmondeley, the 5th Marquess of Cholmondeley, a descendant of Sir Robert Walpole, the first prime minister of Great Britain, in 1913, making her Sybil Cholmondeley, the Marchioness of Cholmondeley. She moved into the family’s Houghton Hall, the Downton Abbey–like 106-room Palladian-style estate on 4,000 acres that was built by Walpole in the 1720s. The architecture, by Colen Campbell and James Gibbs, is commanding: a four-story rectangular block of stone, with turrets at each of the corners. The interiors, by William Kent, are sumptuous. And when Sybil arrived, the collection of art, though it had dwindled over the generations, was remarkable.

Her husband was an avid sportsman and one of the most handsome men of his day. He was also, like many an English aristocrat, short on cash. Sybil, flush with Rothschild riches, restored Houghton to its former glory, though the current marquess also credits her brother, Philip. “Philip commissioned a portrait of himself and one of Sybil and bought a number of other paintings,” says Lord David Cholmondeley, Sybil’s grandson. “Sargent had painted their mother, Aline Sassoon, in 1907, and a first portrait of Sybil as a wedding present in 1913. Philip’s collection of paintings passed to Sybil after the death of her cousin, Hannah Gubbay, who had inherited the Sargents from Philip for her lifetime.”

In 1999, the current marquess sold off $23 million of art and heirlooms from Houghton Hall, including an oil sketch by Rubens and a pair of ormolu swans originally made for Madame de Pompadour, to pay for maintenance. But the estate’s holdings, which include several family portraits by Sargent, remain considerable. “They are so fabulous—I was stunned by them,” Hirshler says of the Sargents in the collection. “There are several great portraits, including one of Aline Rothschild Sassoon in an opera cloak. There is one of Lady Sybil in a Worth Spanish gown, where the dress sets the tone for the painting, and a bust-length portrait of Sybil wrapped in the shawl.”

That may be how the original Sargent cashmere shawl, given by Sargent to Sybil, was found at Houghton Hall. “We do not know the circumstances,” Lord Cholmondeley says.

Jenny Housego eventually found an acquaintance who had seen the original: Warren Adelson, whose galleries in New York and Palm Beach specialize in 19th- and 20th-century American art. Adelson had known Cholmondeley and visited Houghton Hall. “Over the years, my wife and I had seen [the shawl],” Adelson says. “So it was something that Jenny and I had in common. We knew how special it was to the artist, but also that it was such a special object.”

Alas, the shawl was not for sale. Nonetheless, Adelson arranged for Housego to see it in Cholmondeley’s London flat. The room was dark and her flash failed, but she got her first sense of the actual piece. “When I finally was able to lay my hand on the shawl, I was surprised to find that it was made of rather coarse wool, not cashmere,” she recalls. “I got the best pictures I could under the circumstances, but it was most exciting for me to be able to see it, knowing that Sargent himself draped this shawl around my aunt.”

Hirshler, who later saw the original shawl at Houghton Hall with a textile curator from the MFA and a colleague from the Tate Britain in London, was also struck by its connection to the artist’s subjects. “I can’t tell you how thrilling it was to pull it from its casing,” she remembers. “It is always amazing to see a tangible thing. All the people are now gone, so the clothes, props, or jewelry make the works of art come alive in a remarkable way.”

Armed with her exposure to the original and images of other Sargent paintings with the shawl, Housego headed back to India. After founding Kashmir Loom with Kashmiri textile enthusiast Asaf Ali, she started spending time in the region. “Asaf, his two brothers, and their families lived in Kashmir, and I often went to visit them and stayed with them,” Housego recalls. “The beauty of the valley, its lakes with mountains rising out of them, and all the exotic gardens are breathtaking.”

The goal with the Kashmir Loom venture has been to build on the area’s ancient techniques to produce work that has a sense of the human hand. “The region is rife with craft skills, so my years in India obviously attracted me to weaving in Kashmir and the fine gossamer yarn of Pashmina. But while we embraced the age-old techniques, we also challenged our weaving community to innovate and experiment with new ideas.”

While Housego couldn’t possess the original, she realized she could re-create the shawl. She determined that the best process was Kani weaving, a historical and highly complex technique that achieves tremendous detail by using the finest twill tapestry. The project was extremely challenging. “The whole process took about three years just for our first piece to be ready,” Housego explains. “The first was so beautiful that we were all just amazed—its sublime beauty made us forget the time and hard work it took to get there.” The Kashmir Loom version of Sargent’s shawl is an oversize object, four feet wide and more than nine feet long. It is featherlight, in colors softer and brighter than the original: Around the central panel of ivory, the paisley border is in blue, rose, and green. “We continue to make these only with the master weaver who created the first piece,” she says. “Hence, we have made only a few.”

The first went to Jan Adelson, the dealer’s wife. Asaf Ali brought the shawl to New York just in time for an exhibition that was being held at Adelson’s gallery in 2006. “For the opening, I wore a plain navy suit,” Jan remembers, “so that the entire focus was the shawl.”

In 2018, one of the re-created shawls was included in a show at the Museum of Modern Art, “Items: Is Fashion Modern?” The first fashion exhibition at the museum since 1944, it contained 111 objects, including such iconic designs as a 1926 little black dress by Chanel, a 1974 pair of stage platform boots worn by Elton John, and a 1970s stainless steel Datejust watch by Rolex. Three pieces by Kashmir Loom—including the Sargent model—were chosen to represent the Kashmiri shawl, with Paola Antonelli, senior curator of architecture and design at MoMA, visiting the workshops in India to make her selections.

Nearly 19 years since Housego first saw the shawl in that dark flat, the original object continues its storied existence 7,600 miles away. Housego, now 76, suffered a stroke recently and has returned to New Delhi. Lord Cholmondeley has decided to lend the shawl to a pair of major exhibitions in the works that will explore Sargent and fashion, first at the Tate Britain, then at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Warren Adelson hopes that the piece might find a permanent home in the United States, much to the chagrin of Housego. “It would be wonderful if it went to the MFA in Boston,” Adelson says. “The Sargent archives are there, in addition to so many Sargents.”

Jenny Housego admits to the bittersweet nature of the undertaking, creating a reproduction of an object—a family heirloom—that she can never actually possess. Yet she could not be more pleased with the result. “Every time I look at the shawl, I am grateful for the unwavering support of the weavers,” she says. “And I feel a sense of pride when I see someone wearing our Sargent shawl—that I was able to produce something similar to a design that my great-uncle used to admire so much.”

This story originally appeared in the September 2019 issue of ELLE Decor. SUBSCRIBE

You Might Also Like