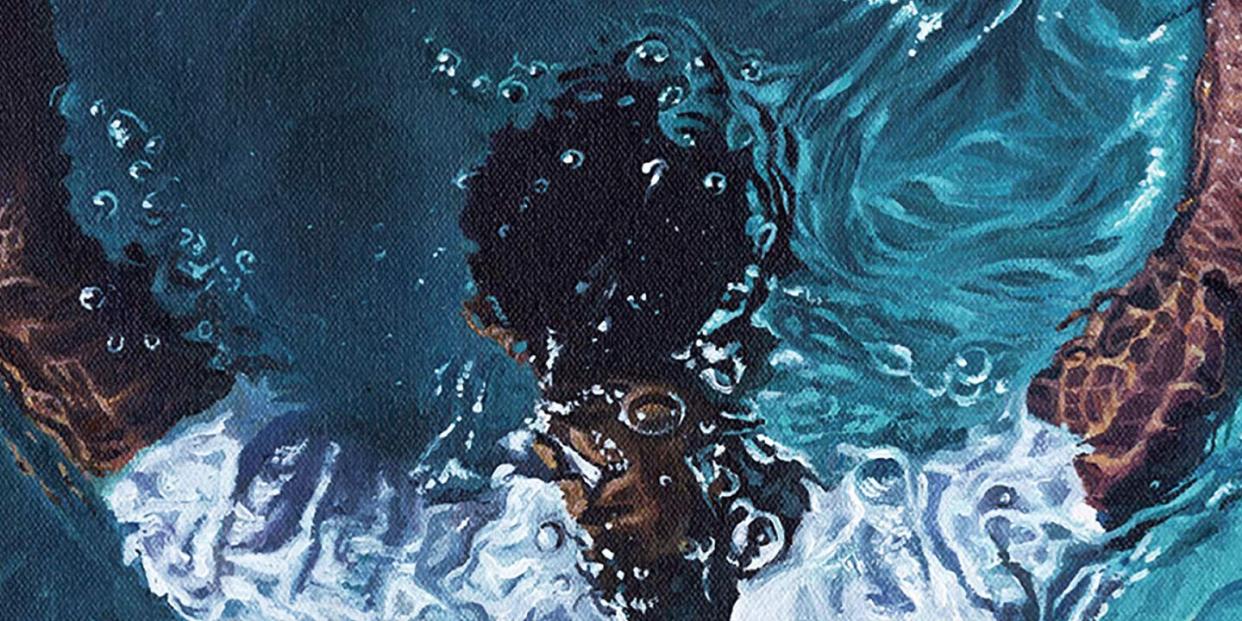

Read an Exclusive Excerpt from Ta-Nehisi Coates's The Water Dancer

In this powerful, exclusive excerpt from Ta-Nehisi Coates’s The Water Dancer—the latest Oprah’s Book Club selection—the novel’s protagonist, Hiram, receives words of wisdom from Thena, the woman who has become a kind of substitute mother. Hiram’s own mother—a slave, as he is—is gone, and he is left to fend for himself on his father’s plantation. What will he do to survive, and perhaps, to escape?

And what of my father? What of the master of Lockless? I knew very early who he was, for my mother had made no secret of the fact, nor did he. From time to time, I would see him on horseback making his tour of the property, and when his eyes met mine he would pause and tip his hat to me. I knew he had sold my mother, for Thena never ceased to remind me of the fact. But I was a boy, seeing in him what boys can’t help but see in their fathers—a mold in which their own manhood might be cast. And more, I was just then beginning to understand the great valley separating the Quality and the Tasked—that the Tasked, hunched low in the fields, carrying the tobacco from hillock to hogshead, led backbreaking lives and that the Quality who lived in the house high above, the seat of Lockless, did not. And knowing this, it was natural that I look to my father, for in him, I saw an emblem of another life— one of splendor and regale. And I knew I had a brother up there, a boy who luxuriated while I labored, and I wondered what right he had to his life of idle pursuit, and what law deeded me to the Task. I needed only some method to elevate my standing, to place me at some post where I might show my own quality. This was my feeling that Sunday when my father made his fateful appearance on the Street.

Thena was in a better mood than normal, sitting out on the stoop, not scowling or running off any of the younger children when they scampered past. I was in back of the quarter, between the fields and the Street, calling out a song:

Oh Lord, trouble so hard

Oh Lord, trouble so hard

Nobody know my troubles but my God

Nobody know nothing but my God

I went on for verse after verse, taking the song from trouble to labor to trouble to hope to trouble to freedom. When I sang the call, I changed my voice to the sound of the lead man in the field, bold and exaggerated. When I sang the response, I took on the voices of the people around me, mimicking them one by one. They were delighted, these elders, and their delight grew as the song extended, verse after verse, till I’d had a chance to mimic them all. But that day, I was not watching the elders. I was watching the white man seated atop the Tennessee Pacer, his hat pulled low, who rode up smiling his approval at my performance. It was my father. He removed his hat, and took a handkerchief from his pocket and mopped his brow. Then he put the hat back on, and reached into his pocket, pulled out something, and flicked it toward me, and I, never taking my eye off of him, caught it with one hand. I stood there for a long moment, locking eyes with him. I could feel a tension behind me: the elders, now afraid that my impudence might bring Harlan’s wrath. But my father just kept smiling, then nodded at me and rode off.

The tension eased and I went back to Thena’s cabin, climbed up to my loft space. I pulled from my pocket the coin my father flipped to me just before he’d ridden off, and I saw that it was copper, with rough uneven edges and a picture of a white man on the front, and on the back there was a goat. Up in that loft, I fingered the rough edges, feeling that I had found my method, my token, my ticket out of the fields and off the Street.

And it happened that next day, after our supper. I peered down from the loft to see Desi and Boss Harlan talking to Thena in low tones. I was afraid for her. I had never seen Desi or Harlan wrathy, but the stories I’d heard were enough. It was said that Boss Harlan once shot a man for using the wrong hoe and Desi once beat a girl in the dairy with a carriage whip. I looked down and saw Thena looking at the floor, nodding occasionally. When Desi and Harlan left, Thena called me down.

In silence she walked me out onto the fields, where no one would eavesdrop. It was now late in the evening. I felt the stiff air of summer releasing into the night. I was all anticipation, feeling I knew what was coming, and when I heard the night sounds of nature all around us like a chorus, I believed they were singing to a grand future.

“Hiram, I know how much you see. And I know that even though we all have to handle the brutal ways of this world, you have handled them better than some of your elders. But it’s bout to get more brutal,” she said.

“Yes, ma’am.”

“White folks come down to say your days in the fields is over, that you going up top. But they ain’t your family, Hiram, I want you to see that. You cannot forget yourself up there, and we cannot forget each other. They calling us up, now, you hear? Us. That trick of yours, and I seen it, we all seen it, it got me too. I am to come up and tend to you, and you might think you have saved me from something, but what you have really done is put me right under their eye.

“We have our own world down here—our own ways of being and talking and laughing, even if you don’t see me doing much of neither. But I got a choice down here. And it ain’t great, but it is ours. Up there, with them right over you . . . well, it’s different.

“You gon have to watch yourself, son. Be careful. Remember like I told you. They ain’t your family, boy. I am more your mother standing right here now than that white man on that horse is your father.”

She was trying to tell me, trying to warn me of what was coming. But my gift was memory, not wisdom.

For more stories like this, sign up for our newsletter.