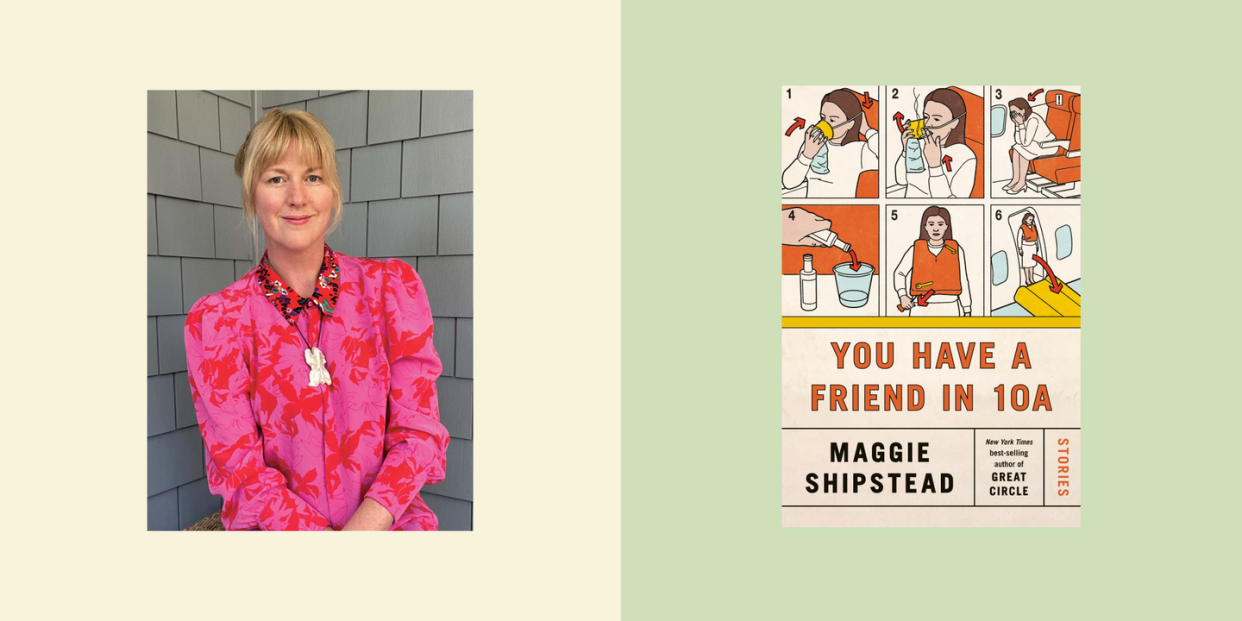

Read an Exclusive Excerpt from Maggie Shipstead’s Latest, “You Have a Friend in 10A”

“In the Olympic Village,” Oprah Daily’s exclusive excerpt from Maggie Shipstead’s forthcoming collection of short stories, turns on a one-night stand between two American athletes—a white male gymnast from Kansas and a Floridian hurdler, a woman of color—as they linger in bed, basking in the afterglow. “They have left the lights on because why not?” Shipstead writes. “They have nothing to show but perfection.… Their bodies have been trained to sweat; they gleam with it.” Both have failed to medal: The hurdler tripped in her heat, while the gymnast tumbled off the pommel horse. Both have watched the lure of gold, the years of hard work, leak out like helium from a balloon. Both wonder aloud about their futures. And from this casual coupling comes a gorgeous meditation on the dimming of expectations and the solace of sex.

A resident of Los Angeles, Shipstead is the author of three novels, including last year’s exhilarating Great Circle, which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize and named one of Oprah Daily’s Favorite Books of 2021. Like the aviatrix in Great Circle, Shipstead is a fearless explorer, navigating the thorny contradictions of our humanity with grace and confidence. —Hamilton Cain, contributing editor at Oprah Daily

In the Olympic Village

The gymnast lies beside the hurdler. The gymnast, a man, is short and white and, toes to shoulders, an isosceles triangle. The hurdler, a woman, is tall and lean and brown. Her hairdresser back in Miami bleached orangey streaks into her hair that are meant to be gold. They were to match her gold-painted acrylic fingernails and the gold track shoes she wore even though she was never expected to medal and did not get past the quarterfinals, in which she’d fallen over the second hurdle. She and the gymnast are in a narrow twin bed, his. His roommate had agreed to sleep across the hall, on the floor between a rings specialist and the gymnastics team’s old warhorse, age twenty-eight, who is at his third Games and spends most of his time icing his knees.

Through the wall, they hear the individual all-around silver medalist having furious sex with a Frenchman who throws the discus. The gymnast, though well-satisfied by the hurdler, listens and feels wistful for that kind of exultant, lusty celebration. He had hoped to bring home a medal. In the team competition, they finished fourth. Of the American men, he was predicted to have the best chance at the all-around—he was second at Worlds—but he fell off the pommel horse and stepped out of bounds on the floor exercise. “Get your head in the game,” his coach had said, holding him by the face. “Focus up.” His teammate, the new silver medalist, had been brilliant on the high bar, better than ever before in his life, and excellent on the floor and solid through the other rotations. He was on all the late-night talk shows, cool in front of the cameras, making little jokes. In the event finals, he picked up another silver and a bronze. He is only twenty.

“Did you know he was gay?” the hurdler asks, curling one long arm up over her head and tapping a gold fingernail against the wall. Her bicep stands up, so distinct he can see exactly where the muscle attaches to the bone.

“Yeah, but he’s not public about it.”

“Maybe now he can be more out.”

The gymnast considers. “I think he might like his limelight to be no-hassle.”

A prolonged groan vibrates through the wall, and the hurdler makes a round-mouthed face of astonishment. “Faster,” she says. “Higher. Stronger.” They giggle and look at the ceiling to avoid each other’s eyes. If they could only lie quietly and make small talk like most first-time lovers, everything would be fine, but the other couple’s sounds remind them of their recent sex and embarrass them.

They have left the lights on because why not? They have nothing to show but perfection. She is utterly hairless, long-limbed, flat and tight in the belly, pale across her breasts and pelvis with stark tan lines from her speed suit. Her toenails are ten chips of gold. He is less elegant but just as functional: powerful bulldog legs, a wide pale chest, abs like the bumps on a turtle ’s shell. The hair on his legs and in his groin is sparse and blond, and tufts of it, trimmed short, sprout from his armpits. Their bodies have been trained to sweat; they gleam with it. The smell in the room is clean but animal.

They had met during the opening ceremonies, when the whole U.S. team marched into the stadium together and around the track. On television, shot from high above, they were five hundred dots rattling around, a casual army out for a stroll. The gymnast and the hurdler found themselves walking side by side, waving and smiling up at no one, everyone, God himself, both wearing the white berets and blue blazers and white pants and shoes issued by the team. They looked like yachtsmen. “We look like yachtsmen,” she remarked (not for the first time—she had tried it out on an NBA player while they were still waiting in the staging area).

“Ahoy!” the gymnast said and then felt stupid. Her face, joyous, looking down on him, was framed by the astral popping of camera flashes and the open, undulating roof of the stadium. Above her beret the night sky was pale with firework smoke. Later, the torch was lit.

She had expected the sex to be more gymnastic somehow. She had imagined a cauldron of chalk beside his bed, him dipping his hands and then brushing them together, white palms emerging from a cloud of dust. Then he would raise his arms overhead and leap onto the bed and… Her imagination failed to come up with what, exactly, he would do, but she thought there would be something, some special move, some impossible position, some defiance of gravity. “You’ll only be happy,” her mother would say, “with a man who’s exempt from the laws of physics.” But he is a farm boy, when you get down to it, and only twenty-two. She is twenty-five and has styled herself as the street-smart kind of track star (scowling on the blocks, wearing dark shades, talking tough) even though her parents live in a big-housed, green-lawned, palm-treed suburb and have a (white) cast-iron jockey to hold up their mailbox. She is not disappointed exactly—the gymnast was very attentive, unlike the last man she slept with, a middle-distance runner who lay motionless on the bed like one of those ancient figurines with the huge phalluses—but she is somewhere short of contentment. She had not anticipated how calloused his hands would be: yellow and rough where the skin has torn and healed a thousand times.

“Does everyone make a joke about sticking the dismount?” she asks.

“That’s funny,” he says. “And what do you mean everyone?”

“What are you going to do after this?”

He rolls onto his side to face her. “I thought we’d go to sleep,” he says, “but if you want to go out, I can rally.”

“No, I mean after the Olympics.”

“Oh.” He has a mole on one cheek, and it vanishes into a crevice of his smile. “I’m going back to Wichita to coach gymnastics.”

“Like at a college?”

The mole reappears. Its presence on his face is the one asymmetrical thing about him, but, taken alone, it is brown and perfectly circular. “No, at a gym. For kids. I really like kids. Someday I want to have my own gym.”

“You know,” she says, “it’s nice to hear a man say he likes kids without worrying about sounding creepy.”

His eyes, pale blue with short blond lashes, move over her face. He is not sure if she is kidding and, if she is, what she means exactly. “I have five little brothers and sisters,” he says.

She is an only child and feels an only child’s shock at the notion of a family that is not just three points connected by three lines, but a polyhedron. “Five?” she says. “Jesus.”

He nods. His buzz cut rasps on the pillowcase. “Matthew, Mark, Luke, Mary, Rachel, and me.”

She starts to say Jesus again but stops herself. Her mother is Catholic, but the hurdler herself does not believe. At track meets, her mother pulls a rosary through her trembling fingers; she was holding it today when God let the hurdler fall in the quarterfinals. Now she is asleep in her hotel on the other side of this foreign city. She believes her daughter is a virgin. The cries of the silver medalist and his Frenchman rise to what the hurdler hopes is a final crescendo. “Sacré bleu!” she says.

The gymnast’s mole vanishes again. In a deep, discus-throwing voice, he says, “Ah, oui. Baisez-moi, homoncule!”

Twelve days passed between the opening ceremonies and this night when the hurdler and the gymnast are in bed. During those days, they crossed paths often enough that destiny and not just coincidence seemed to be in play. They bumped into each other at meals and passing through the Village gates and in the lounges where athletes gathered to watch other sports and scout possible flings. While the gymnast and the hurdler stood chatting and waiting for their chicken sandwiches or for their IDs to be checked, they remembered flashbulbs and firework smoke, plumes of flame dancing up from the torch. Sex during competition was frowned upon: Passion drains the body’s resources and wilds the mind. The swimmers were among the first to be done, and they swept through the Village like a chlorinous band of pillagers, their tan faces marked with white bandit masks from their goggles.

The gymnast and the hurdler bumped into each other at the event finals for women’s gymnastics. She had requested tickets partly because she was hoping to see him and partly because she has always loved gymnastics. As a child, she wanted to be a gymnast until it became obvious she would be too tall. “But she’s very, very fast,” her coach told her mother, watching her barrel down the long blue runway and leapfrog the vault. “Very fast.”

The hurdler and the gymnast sat together. They had chosen each other. They were waiting to be liberated from their sports.

“How was your day?” she asked him.

“Good,” he said, watching his teammate on the balance beam. “Did some practice. Did some PT. Looked at tapes. You?”

“Pretty much the same.”

The girl on the beam was tiny and precisely wrought. She bent backward into a handstand. Her legs opened parallel to the beam, and there was something pagan and offertory about the flatness of her crotch, her right angles, the T she made, like an altar. Then a foot came down and she was right side up and upside down again and right side up. “Let’s go, Katie!” shouted the gymnast as the girl paused with her arms raised, back arched, facing the crowd, her ribs showing through her leotard.

“Do you know her?” the hurdler asked.

“Sure,” he said. Staring down at the beam, he rested his chin on his fists. He must have understood what the hurdler was asking, because he said, “She’s a good kid. Only sixteen. Really handles the pressure.”

The hurdler envied the attention the girl commanded. There weren’t seven other girls alongside her on seven other beams, the way the hurdler always shared the track. This girl could stand there all alone, like a bird on a narrow branch above a sea of blue mats, her dainty sternum betraying the flutter of her miniature heart, her hair full of gel and glitter and barrettes. Everyone would watch. She went flip-flopping the length of the beam and flew into the air. On landing, she teetered sideways, crossing one leg over the other, and the hurdler was glad.

“Homunculus,” the hurdler says. “I learned that word in Latin. I didn’t know it existed in French.”

“My mom called me that when I was little,” he says. “You took Latin?”

“I went to Catholic school.” “Are you Catholic?”

“My mother is. Cuban-style.”

He leaves it at that. His mother, picking him up from gymnastics: “Allons-y, homoncule. In the car.” In the gym, from the first, he had loved the different apparatuses, unforgiving steel and graphite, not alive and helpful like they looked on TV. A dust, probably toxic, rose from a pit full of foam blocks and floated in the light that angled through the high windows.

Stroking the orange streaks in the hurdler’s hair, the gymnast thinks about the moment when he fell off the pommel horse. He remembers being up on the handles, his legs rotating around him, feet drawing circles in space, rocking on his hands one-two one-two to let his thighs swing under, and he remembers turning and reaching and closing his fingers around the shocking nothingness, emptier than air, that exists where something solid is expected. The world had dropped out from under him so quickly and with such finality: the tipping crowd, the side of the horse, the lights in the raftered ceiling, and then the mat smacking him on the hip. On the sidelines, his coach flung his fist at the floor like someone skipping a stone. The gymnast had stood, walked to the chalk bucket and back, saluted the judges, and sprang up to finish his routine.

Through the wall, the discus thrower and the silver medalist have gone quiet. The gymnast wants them to be smoking cigarettes, but there is no smoking in the Village. He could tell the hurdler had been surprised when he spoke French. His mother is French, a long-ago exchange student who fell in love with his father and Jesus and came to accept the astonishing flatness of Kansas.

“What are you going to do after this?” he asks the hurdler. “Probably rally and go to a bar,” she says.

“Cool,” he says. “Just what I was thinking. Let’s go.”

She is the little spoon, though she is taller, and she frowns back over her shoulder at him. “I was kidding.”

“So was I.”

“Oh.”

“So,” he tries again, “what are you going to do?”

He feels tension come into her body. “I don’t know,” she says. “Anything but motivational speaking.” Her shoulder, contoured with muscle, lifts toward her ear, less a shrug than a hunch. She rolls away, onto her stomach, and he puts his hand on the small of her back. Even there she is hard with muscle. Before he went to bed with the hurdler he would have expected to be thinking of his girlfriend in the wake of an infidelity. Realizing he is not thinking of her, he thinks of her. What time is it in Kansas? He doesn’t know. Daytime. She is at work. She is small, a former gymnast, now a preschool teacher. He loves her; he will probably marry her. He had not planned to be unfaithful, but he doesn’t feel particularly bad about what has happened. He had heard the stories about the Village—thousands of perfect bodies crammed together and hopped up on pride, ambition, euphoria, pain, relief, disappointment, everything else—and he has found they are true but also insufficient.

“Banging is like an intramural sport there,” the twenty-eight- year-old warhorse said during training camp, taping a bag of ice to his knee. “You feel like you’re going against the Olympic spirit not to get some.”

But opportunity is not an explanation; he has passed up plenty of opportunities before. Something is in the air here. As a child he had liked to imagine himself leaving glowing trails in the air when he practiced his routine, like bioluminescence, so that his movements would not be lost but would be recorded in space. Now he imagines what it would be like if everyone left such trails, if glowing circles spooled the track, if a mist rose from the pool and hung over the city, if a bumpy line followed behind the hurdler, if light shot from the gymnast’s own whirling feet on the pommel horse as though from a Rain Bird sprinkler. He imagines all that energy, all those lingering vectors, mixing in the air and binding everyone together. Sex, he thinks, is both an extension of and a relief from the pointlessness of sport. They swim back and forth, run around and around, paddle from one buoy to another, bicycle to nowhere. Nothing is created but speed, momentum, heat, disturbances in air and water. However far someone can throw a javelin, it will still not be very far, all things considered, and it will not hit anything except turf. They mate in their twin beds, miming creation.

The gymnast and the hurdler did not watch each other compete. Their schedules conflicted. But she saw him on TV when she was stretching on the floor of one of the lounges. They aired a little segment about him in the first week, before his events had begun, with stylized shots of him wearing a determined expression in front of the parallel bars, the pommel horse, the vault. “These shoulders,” the narrator said over a close-up of the gymnast’s knotted back crucified between the rings, “carry the hopes of a nation.” His hands rotated in slow motion around the high bar, then released, and the bar bounced in empty space, shedding chalk dust.

The hurdler wonders about this naked stranger, this triangle of muscle, this homoncule. Why shouldn’t he know a word she doesn’t? Just because he’s into Jesus and is from Kansas and loves children is no reason for him not to speak French. She also saw a replay on TV of when he fell off the pommel horse. He had looked so bewildered, sitting on the blue mat, and then something had crossed his face that she didn’t understand. Relief? At the end of the suspense? The pressure? She can’t imagine having been a favorite. Even if she hadn’t fallen, her body simply couldn’t have run fast enough to get her onto the podium. Her desire, desperation even, to win is no match for the limitations of fast-twitch muscles and lung capacity, the dark alchemy of glucose and lactic acid, the length of a femur in relation to a tibia. The woman who won gold is a fearsome machine, over six feet tall, perfectly engineered to run. After the closing ceremonies, the hurdler plans to sit by her parents’ pool for a few months and think things through. She will allow herself to gain five or ten pounds. Then she will face the strange fact that she has many decades left to live.

After gymnastics, she had tried dance (too tall again), and tennis (weak backhand), and cross-country (miserable), then track, and then hurdles, and this is what all those years of agony, the runs, the weights, the pop-eyed, screaming, tyrannical coaches, the ankle surgeries were for: a tryst with a gymnast before she goes back to Florida. She thinks about her foot catching on that hurdle. It was only this morning. She had come off the blocks all wrong and barely made it over the first hurdle; her stride was too short; her rhythm was choppy; the second hurdle was too far away when she made her leap, and she went down, the length of her spilling onto the track with her gold-tipped hands splayed out in front, her golden shoes at the end of her long, long legs. The rubber smell of the track, the sound of the crowd—she could have lain there forever if only to avoid getting up.

He rolls her over and climbs on top, and she is conscious of how short he is, his feet between her calves. They kiss until they are startled by a loud pop! from next door. “Champagne,” he says.

She makes a face. “I was afraid Black September was here.”

“Who?”

She regrets having mentioned it. Her pillow talk is rusty. “You know. Munich. When terrorists killed those Israeli athletes.”

“Oh.” He rolls off her again and frowns, elongating his mole. “Oh, right. That picture. The guy in the ski mask on the balcony.”

“Yeah.”

“Security seems pretty tight here.”

“Yeah. It was a dumb joke. Not in good taste.”

“It’s okay.” He waits a minute, and then with the air of changing the subject, he says, “My teammate said that sex in the Village is like an intramural sport. He said they should give out medals for it.”

“Do you think you should get a medal?” She is irritated without knowing why.

“No.” He looks hurt. “No, I just thought it was funny.”

“I’ve noticed that, for men, medals are like this incredibly powerful pheromone. Any guy with a medal has a harem full of groupies the second he gets off the stand. But it’s not the same for girls who medal. Have you noticed that?”

He thinks. “No.”

“It’s true,” she insists. “It’s like there’s something off-putting and unladylike about trying hard enough to win. Or about being that strong.”

She feels stupid for letting her hairdresser put the streaks in. They are so garish, so expressive of hopeless aspiration, and the bleach has made her hair brittle and rough. Poor girl, people must have said: She thought she was going to win and then she fell in the quarterfinals. But the hurdler never thought she was going to win. She just wanted to participate in the hope. A miracle would have been needed for her even to make the finals. Most years, she wouldn’t have qualified for the team, but a couple of girls were out with injuries, and she ran a personal best at Trials. At the Games, she is part of the general population of athletes, the middle fifty percent, which hardly seems fair, given how fast she is—she was NCAA champion two years in a row. But here she is one insignificant inch of the dark, anonymous curtain against which the stars take their bows. The Olympic Village, cross-sectioned like a dollhouse, would be gloomy with disappointment, she thinks, and pinpricked with spots of triumph too bright to look at. How many of its rooms, she wonders, are occupied by couples like them?

He is playing with her hair again. “I would like you even if you’d won a medal.”

She realizes she is about to cry and that she doesn’t want to do it in front of him. He would be kind and consoling, but this cry must be solitary. She had thought being with him might stave it off. “Remember the opening ceremonies?” she says.

“Sure.”

“I wish that could be the only thing I remember from this.”

She has stung him, she sees, and she feels remorse but also grim satisfaction.

“You don’t mean that,” he says. “You’ll want to remember everything.”

“Maybe you’re right,” she says. “But I should go.”

“I was hoping you’d stay.”

She sits up, and he gazes placidly at her breasts. “Why?” she asks.

He indents her left nipple with the tip of his index finger, like somebody pressing an elevator button. “This was fun.”

“But now it’s over.” She hears how dramatic she sounds and, to cover her embarrassment, drops her voice even lower and gives him a wry smile. “Everything,” she intones, “is over.”

“I wish you’d stay.”

She shrugs and gets out of bed.

When she is gone, he finds he doesn’t miss her. The bed is small enough already. He had thought, a few hours ago when he met her for dinner, that they would have more time together, a real affair, but now he decides that the difference between one night and three doesn’t matter. Their encounter is probably the only one-night stand he’ll ever have. She had decided he wasn’t very smart—he knows this and is not offended. Her opinion won’t make him smarter or dumber, and he has never thought of himself as being particularly smart, anyway. He remembers chalking the high bar during team warm-ups, dangling from it like an orangutan and shuffling sideways, sidestepping his chalky hands from one end to the other to leave behind an even layer of white dust. He had been terrified then, looking up at the blank scoreboard, but now he has failed and survived and fear seems like something he will never have to experience again.

The silver medalist and the Frenchman start back up, and the gymnast puts a pillow over his head.

The hurdler, walking down the hallway and thinking about the gymnast, decides it’s probably for the best that he didn’t win a medal because she doesn’t think he would have known what to do with all those choices. Now he will marry a nice woman and someday own a gym with bars and vaults and a pit full of foam blocks. He will have the infinite Kansas horizon, the perfect white disk of the sun. She sees herself swimming through the shadows of palm trees in her parents’ turquoise pool. She sees the gymnast’s unborn children flying through the air, twisting and flipping, never needing to land.

You Might Also Like