Rashid Johnson Reimagines ‘Native Son’

Rashid Johnson has been thinking lately about microphones.

“In the current state that we’re living in, people have so much enthusiasm to have their voices more roundly and loudly heard,” the artist explains from his industrial studio in Bushwick on a recent afternoon. He was describing the motivation for several new works and works-in-progress on the wall for an upcoming show. The mixed-media pieces have built-in speakers, which he plans to utilize to create unconventional outlets for amplification, inviting poets and speakers into the art gallery environment. Touching upon the symbolism of a microphone, Johnson brings up the woman’s suffrage movement, Martin Luther King Jr.’s march in Washington, the fact that hip-hop is the only musical genre in which the lyricist directly mentions the mic.

Related stories

Molly Gordon, Hollywood's New Comedic Darling

Hero Fiennes Tiffin Is Here to Sweep You Off Your Feet

SXSW 2019: Nina Dobrev on Women in the Workplace and Writing Rom-Coms

“This opportunity to amplify one’s voice, the agency that comes as a result of it, is such an incredible historical signifier,” he adds.

Amplifying one’s voice can take many different forms. The 42-year-old contemporary artist, who has established himself in the art world through his conceptual works, turned to narrative film as the loudest vehicle for his latest message, a new cinematic adaptation of Richard Wright’s novel “Native Son” set in modern-day Chicago. The film, which stars young-but-soaring actors Ashton Sanders and Kiki Layne, premiered at Sundance in January and was acquired by HBO ahead of the festival for an April 6 release.

“There were several people in tears, several people who were quite emotional; you could see the energy that they received from some of the ideas in the film, it triggered things in them,” says Johnson, reflecting on reaction to the film in Park City, Utah.

Reflecting on the current social climate ultimately influenced Johnson’s interest in revisiting Wright’s seminal 1940 novel, which was adapted onscreen in 1951 and 1986. Recognizing at the outset that adding to that existing canon of work would add baggage to the project, Johnson notes that this was in fact a motivating factor. The artist was interested in engaging with audience preconceptions, both in terms of the story and what they expect from an onscreen black male protagonist.

“It just always sat with me as such a complicated story,” says Johnson of the novel and its antihero, Bigger. “It was during the Obama administration that I thought to myself, this is a really interesting time to explore a character that is more problematic and that has a different kind of lens to which we can view him. Because during the Obama administration, in particular, I think it became unimpeachable that there are black characters who are quite exceptional. And it became less the responsibility of the black artist to punctuate the concerns of black exceptionalism, and it became more an opportunity for us to speak to the different complexities within the experience of the black protagonist. Bigger was, for me, born there.”

Johnson credits his mother for introducing him to the book as a teenager. She prefaced the introduction by adding that she found the book problematic and at points troubling.

“So that piqued my interest right away,” Johnson says. “In my mind, imperfections and the flaws and the pimples on things that make them challenging and harder to read are the things that make them worth engaging with.”

The new film, written by Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright and screenwriter Suzan-Lori Parks, deviates from the novel in both structure and set-up. Even the seemingly small changes and tweaks in the character’s environment and personality affect the story in major ways. Nonetheless, Bigger’s ultimate fate remains the same.

“One of the criticisms of the book by writers and thinkers after Wright’s initial delivery of the book into the world was that Bigger was a character who lacked agency, or the opportunity to dictate his own path,” says Johnson. “In 2019, although we’re facing incredible obstacles, we are still living in a world where we have begun to understand that all of these groups still have a certain agency and opportunity to at least begin to protect themselves, build narratives, think through and explore complicated themes and ideas and concerns from a position of agency.”

Using that as a launching pad, perhaps most notable of all is their choice to elevate Bigger’s economic background.

“Some of the things Bigger was going to be facing around race and class were best explored if he had a sense of opportunity to some degree, and that opportunity again would be the thing that could save him,” Johnson says. “The psychological space that he inhabits and the circumstances that he is then exposed to, then puts him back into a position of, to some degree, pragmatically being fated.”

A connection to Chicago permeates much of the project. Like Bigger, Johnson grew up in Chicago, where he also attended art school before moving to New York at 25. Both of his leads, Sanders and Layne, studied acting at DePaul University; both also had their breakout roles in films directed by Barry Jenkins.

“As we were developing who this character would be and how he would understand Bigger, Ashton’s face just kept popping up to me,” says Johnson, describing the 23-year-old actor as his only choice for the role. Opting to present an alternative view of black male masculinity, Sanders’ lanky frame aided in presenting Bigger as a character who’s thin but strong, with a fragility that challenges the viewers’ expectations.

“[Bigger] loves punk, he loves Beethoven, he’s engaged, he’s dynamic, and he’s strong,” says Johnson. “But it’s not just his physical presence that gives us a sense of that strength; it’s his intellectual engagement, his cultural sensitivity, and his sense of self.”

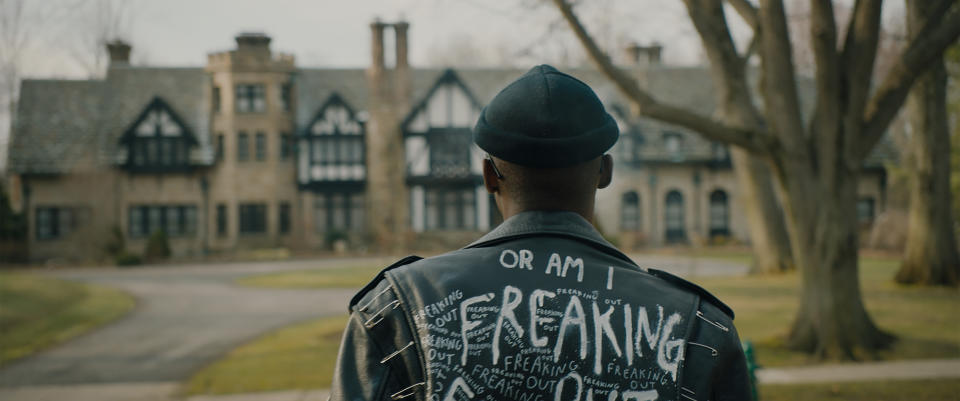

One very visual totem of that strength was aided through costume. Throughout the film, Bigger dons a black leather jacket with messages scrawled on it.

“It’s a shield that expresses that he has a way that he sees the world and that he’s willing to allow you to see that directly on his body.” he says. “I think fashion often allows us to say something about ourselves prior to even opening our own mouths.”

With the film’s release on the horizon, Johnson is looking toward a slate of upcoming international shows. In April, he plans to direct a balletic video art piece in Aspen. While another feature film isn’t currently in the works, Johnson notes that he’s not closing the door on the possibility down the line.

“Right now in the world that we’re living in, storytelling and different kinds of voices and different ways of telling stories is just enormously important,” he adds. “It’s more important than I ever thought it was.”

It certainly allows him a large platform to tell stories to a wider, more diverse demographic, over a longer period of time.

“It’s really rare to own that much of another person’s time, and it’s quite a responsibility, in all honesty, to beg that much time from someone,” he agrees. “And within that time [you want to] give them something that is rewarding. You want it to be educational but not didactic, you want to be thoughtful, you want it to be engaging,” he continues.

“And most of all, you want them to want to do it again with you.”

More from the Eye:

Molly Gordon, Hollywood’s New Comedic Darling

Hero Fiennes Tiffin Is Here to Sweep You Off Your Feet

Launch Gallery: Inside Artist-Director Rashid Johnson's Brooklyn Studio

Sign up for WWD's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.