Rap Legend Redman Joined Jennifer Lopez on ‘SNL,’ Reminding Us That Redman Makes Everything Better

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

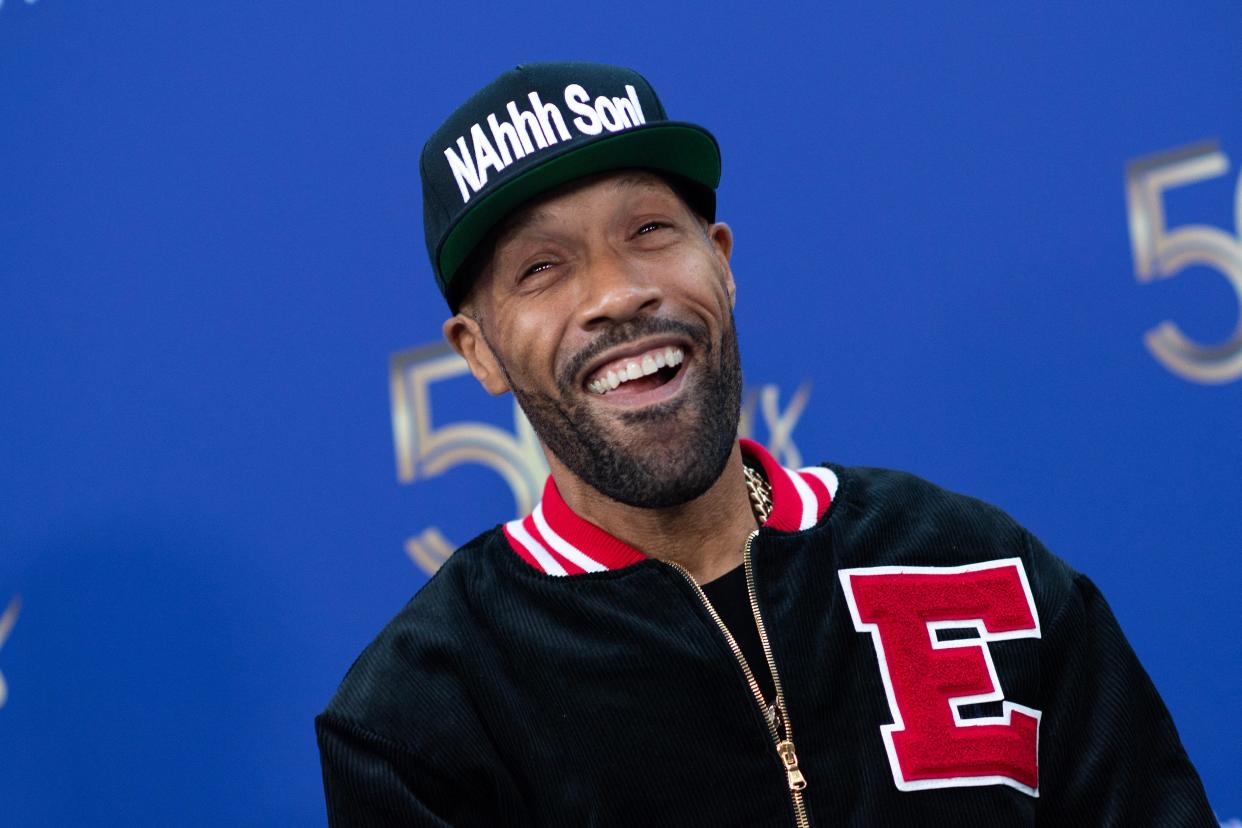

VALERIE MACON/Getty Images

Jennifer Lopez was not the only geriatric millennial icon onstage this week on Saturday Night Live. Like a minor god arriving on a cloud, Redman materialized to rap on a remix of Lopez’s “Can’t Get Enough” that interpolated his 1998 hit “Da Goodness,” and the hip-hop cognoscenti saluted.

For the uninitiated (read: everyone under 35): In the boom-and-bust cycles of late-’90s/early-2000s post-Golden Age rap, Redman was everybody’s friend. He provided effortless, waggish verses for all who wanted them, and made shaggy, strange, singular albums. He is also a study in contradictions. His core competencies were insouciant weed raps, sex farce, and working-class crime narrative that could only come from a son of Newark. But this belied Redman’s impeccable rhyme patterns, his gimlet eye for detail, and his wry clear voice, which delivered irony better than any other rapper not named Biggie Smalls.

Christina Aguilera hired him for a guest verse when she wanted to shed her teenage persona on “Dirrty.” De La Soul used him on “Oooh” to leaven their bookish vibes and give them a shot at a hit single. Limp Bizkit brought him on when they needed to remix “Rollin’” after the original song became pro wrestler The Undertaker’s entrance music—a moment that belongs in the 2000s canon along with Mountain Dew Code Red and Karl Rove. Eminem ranked him ahead of all his industry peers on “Collapse” and, for the young people reading, Lil Durk named a song after him.

Saturday Night Live - Season 49

At his best, Redman is like if Bad Brains and EPMD (whose Erick Sermon first discovered him) and the most amiable, black-light-and-cartoons-loving, secretly smart hometown stoner ended up with one excellent album, three more good ones, no bad ones, a loveable, R-rated blaxploitation campus movie (How High, where he and Method Man end up at Harvard) and the greatest episode of MTV Cribs ever.

1996’s Muddy Waters, his third, is the album to begin with. Produced largely by Sermon and Redman himself, the sound is one of Redman taking himself a bit more seriously. Filled with scratches and dusty samples, the best songs—like “Iz He 4 Real” “Whateva Man” and “Pick It Up”—unspool the same set of references (blunts, blunders and brawls), but with tighter cadences and end rhymes: “Styles stay deeper than orca, I float the seven seas with ease / Did more drugs than pharmacies / So call me that lyrical Genovese, you can't compare / Get you steppin’ like stairs, frats, sororities/ Don't make me bring it on back, I fuck up the majority.”

Ras Kass described Redman’s charm on Muddy Waters simply: “He’d have that one line that didn’t make sense.” That’s what made Redman special. No East Coast rapper in the 90s could touch Nas’s preciosity or Biggie’s craft or DMX’s fury. But Redman made the idiosyncratic cool. He knew dorm-room stoners of all colors loved him so he rapped about that. He knew he was puckish, so he rapped about that. He knew he’d never leave Newark so he rapped about that.

On that iconic MTV Cribs episode, he simply showed the camera crew around his messy two-bedroom in Jersey. Gaming console on the floor. Buddy passed out on the floor. DVD porn. Crumpled twenties in a shoe box. It wasn’t a joke: the most organized part of the house was the room with his keyboards and turntables and recording equipment. Here was a glimpse of an artist’s day-to-day. Years later, Redman revealed that MTV had tried to convince him to rent another, nicer house for the show instead, as many Cribs subjects apparently did. Redman refused. He wanted to deliver real life.

That authenticity kept him relevant and earned him affection from unexpected places. In college, I knew easygoing dudes whose bands played buggy Neil Young covers who thought Redman was the perfect tonic to the ersatz post-Biggie “more guns, more jewels” rappers. I knew crate digging rap fans who thought his similes and breath control put him in a tradition going back to The Sugarhill Gang. Dealers revered him as a patron saint. Redman’s constituency reminds me of Ferris Bueller’s. Burnouts, jam-band bassists, rap purists, the scattered, fun girl in the snobby sorority, the shaggy and sleepy of all genders—they all thought he was a righteous dude.

On Drink Champs a few years back, Redman told stories about the origins of the NYC weed scene, being close to the dealer who’d be memorialized as the mythical Branson, and how he met Method Man, the partner that would define his career. Their duo album, 1999’s Blackout!, is an unquestioned classic, Method Man’s brawn dancing perfectly with Redman’s lean, almost vulpine wit. Redman darts in and out with perfect couplets: “I scored 1.1 on my SAT / and still push a whip with a left and right AC.”

He's released music at a steady clip since his peak in the early 2000s. He and Meth starred in a movie together and Redman himself had a significant role in a Chucky sequel. In the cult video game Def Jam: Fight for NY —yes, the one where rappers have WWE-esque brawls—his character Doc is central to the plot. No one will ever have his career again.

I wonder if pot’s path toward full legalization made Redman a product of his time. The double entendres in his lines and light scandal of inviting anyone at any time to light up feel a bit daddish now. It’s not his fault. In many ways they’re art of an older era. We’re a country of dispensaries built like Apple Stores and the world’s richest man burning the saddest joint on a petite MMA conspiracy theorist’s podcast.

If Jay-Z was the Millennial rapper for aspirations and branding and getting an MBA, Redman was the rapper for the hometown people, people always greeted with a ravioli bag and love, who were much smarter than they appeared and comprehensively unbothered.

So may his SNL appearance create a moment to give Redman more flowers. His appearance was strange, excellent, and evanesced so swiftly it felt like a vision. As he said on Drink Champs: “I wanted to be different.” In a moment in rap when autotune and monotone and nearly identical production styles have flattened out the ragged corners of big-budget rap, I hope that youngsters and old heads alike can let Redman give them a breath of fresh stank air.

Originally Appeared on GQ