I ran away from a troubled teen program and escaped for good. This is my story

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Lately, I’ve been having nightmares that I’m back in boarding school.

Each dream begins innocuously enough. I find myself walking down a hallway past classmates standing in line in the dining hall. Sometimes, one of them is suddenly tackled to the ground. They struggle under the weight of fellow student who tries to restrain them. Other times, I’m sitting in a corner with my eyes fixed on a blank wall as days stretch into weeks and months.

The faces are all a blur in the dreams, but the swirl of fear and distress, the pounding in my chest and the rage that I feel are sharp.

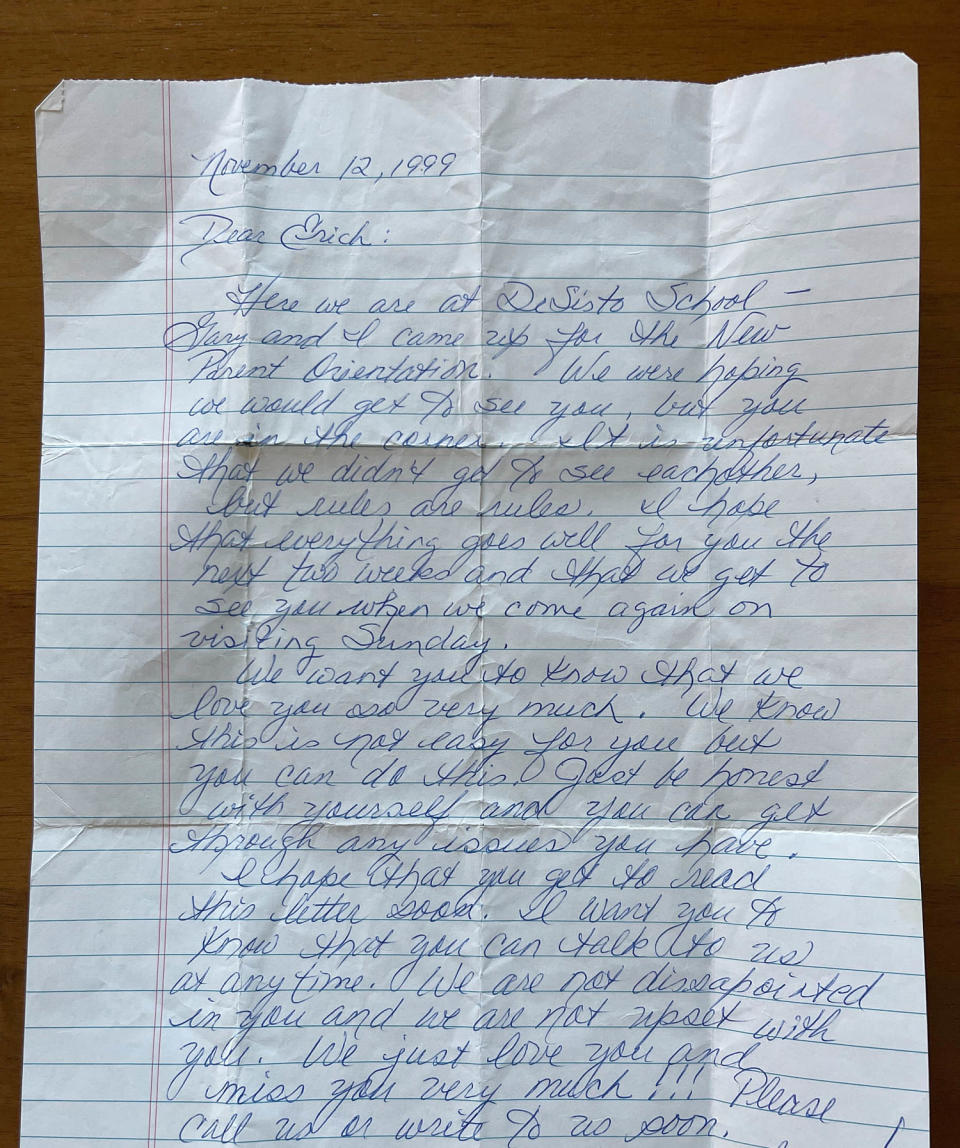

The dreams are more like memories, as tangible as they were to me in the days after my parents dropped me off at The DeSisto School in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, and I began to realize that although I was surrounded by people, I was desperately alone.

I started watching the true crime documentary “The Program,” directed by troubled teen program alum Katherine Kubler, at my sister-in-law’s recommendation. “You guys have to see this,” she said soon after it debuted, certain that my wife and I would have seen nothing like it.

As she laid out the documentary's details — a group of teens sent off to a behavior modification facility — I realized that she was describing a story that was not unlike the one I experienced as a teenager.

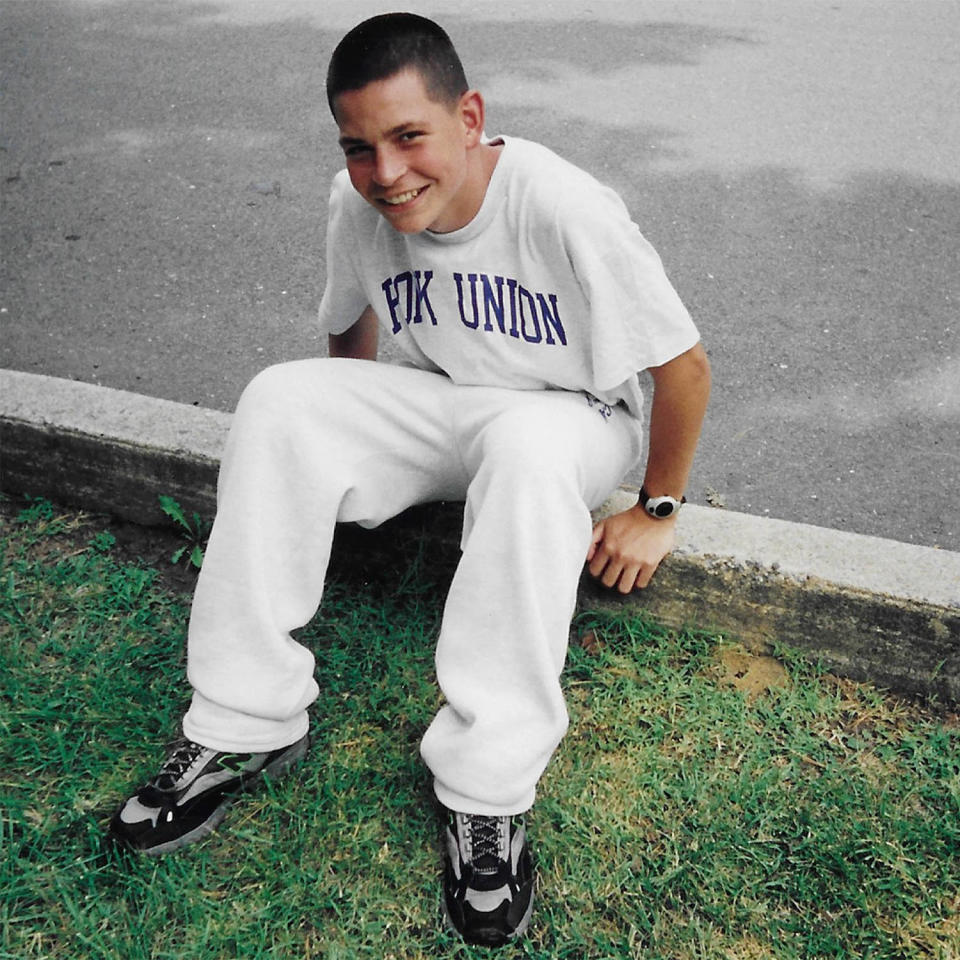

Like Kubler, I was a high school student when my parents determined that I was beyond their control. I’d been diagnosed with ADHD and was expelled from two schools, the second one being a military academy.

While Kubler experienced the shock of being taken away by strangers and dropped off at a school without any parental contact or explanation of where she was going, I actually picked out DeSisto.

After collecting me from the military school, my mother sat me down in her office, handed me a few brochures, and, to my surprise, told me to find the next school that I would go to.

Eventually, I came across one for DeSisto, which sold a story about a therapeutic environment for artistic kids who were misunderstood. The school featured images of a picturesque estate that drew me in.

Not long after selecting DeSisto, I was driving up to an idyllic Massachusetts town nestled in the mountains. My mother, step-father and I spent my last night before I headed to DeSisto at a bed and breakfast. It was October, and I still remember the autumn leaves and their colors. I took a long bath in a clawfoot tub and savored a king-sized Snickers bar. I had a feeling it was going to be my last for a long time.

I never suspected that within 48 hours of my arrival, I would be sobbing, pleading to be sent back home.

Immediately after entering the gated property, I realized I had landed in a new society, governed by new rules. The entire campus was in the middle of a two-week-long sit-in meeting, prompted by someone graffitiing the boys’ bathroom. Pressure was put on every student until someone confessed or was outed by a peer.

“Sit in” was the start of new vocabulary I became fluent in, reflective of DeSisto’s authoritarian streak.

Immediately after entering the gated property, I realized I had landed in a new society, governed by new rules.

Rather than friends, new kids were assigned “buddies.” Two students were paired together and responsible, by proxy, for whatever their buddy did or said. We could never be more than a hand’s reach away from a buddy or from another student, for that matter. We were required to travel in groups of three, the reason being that a pair could come up with a notion to run off, but adding an additional student into the mix undermined cohesion.

Every morning was anxiety ridden because of all the potential punishments.

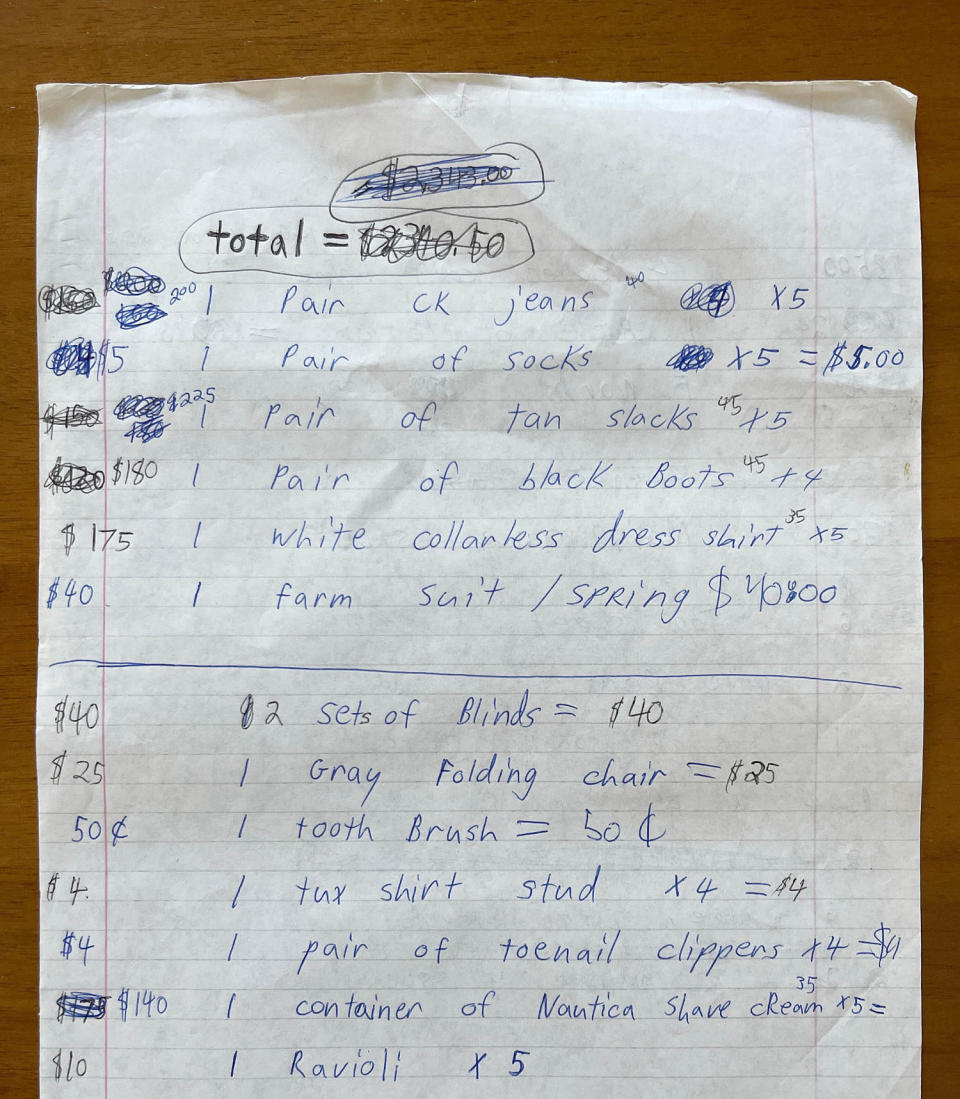

If you broke the dress code or stained your outfit, you were "suited" and had to wear a formal suit, including tie and dress socks, until you were given reprieve. If the issue continued, you would be "sheeted," which meant you weren’t allowed to wear clothes — just a sheet tied like a toga.

“Ghosted” meant everyone had to ignore your presence. “Silenced” meant you weren’t allowed to make a sound. “No PC” meant you couldn’t have physical contact with anyone. “Hand held” meant you had to hold hands, sometimes for hours, no matter what tasks needed to be done.

During "limit structures," students were held to the ground by other students and verbally assaulted with personal jabs. The goal was to break a person down.

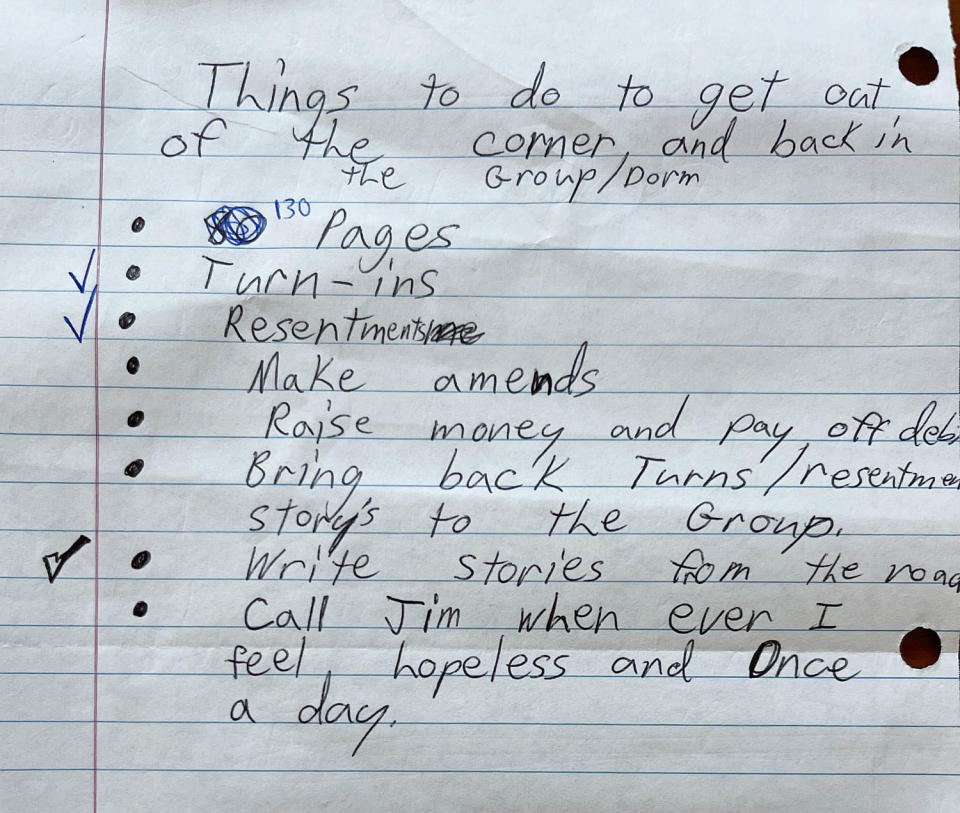

“Cornering” was DeSisto’s version of a time-out. We had to sit in a metal chair facing a corner. Once, I was cornered for 60 days. I was only able to get up to use the bathroom and eat. I was allowed limited access to showers. No phone calls with parents or interactions with other students. Nothing. I was so furious and despondent that, at some point, I began to rattle off the F-word over and over again. That was the only curse word we weren’t allowed to say. Each time I said it warranted a $1 penalty.

Then, there was the Farm, the prison of DeSisto. There, students lived separated from the rest of campus, deprived of all possessions including personal clothing. We couldn’t contact home. We had to do everything as a group — including bathroom time. Entire dorms were farmed at once. For example, if the nightly dorm meeting went past midnight because we couldn’t reach a group consensus, we all would be farmed. Happened all the time.

Once, I was withheld from seeing my parents because I was accused of violence for smacking my hand on a sofa during a dorm meeting. This was devastating, and a defining moment when I realized I had no freedom.

My days at DeSisto were tedious and toiling. I was there for just under three years, it still feels like a decade. Every day dragged, and every week and month was so painfully slow that I just lived day to day. I saw how the desperate circumstances took a toll on all of us.

Some of my fellow students went along with situations most would see as inappropriate in exchange for rewards and freedom. Students didn’t have access to television, but some of the administrators had them in their rooms. Once, a male staffer of the school invited two other boys and me to watch a movie in his quarters. He’d been sitting with his arms around them on the sofa when he asked me to come sit by him. I got a funny feeling and said no. I was never invited back. Later, as I tried to make sense of the things that happened there and connected with former students, I heard stories that confirmed my instincts weren’t wrong.

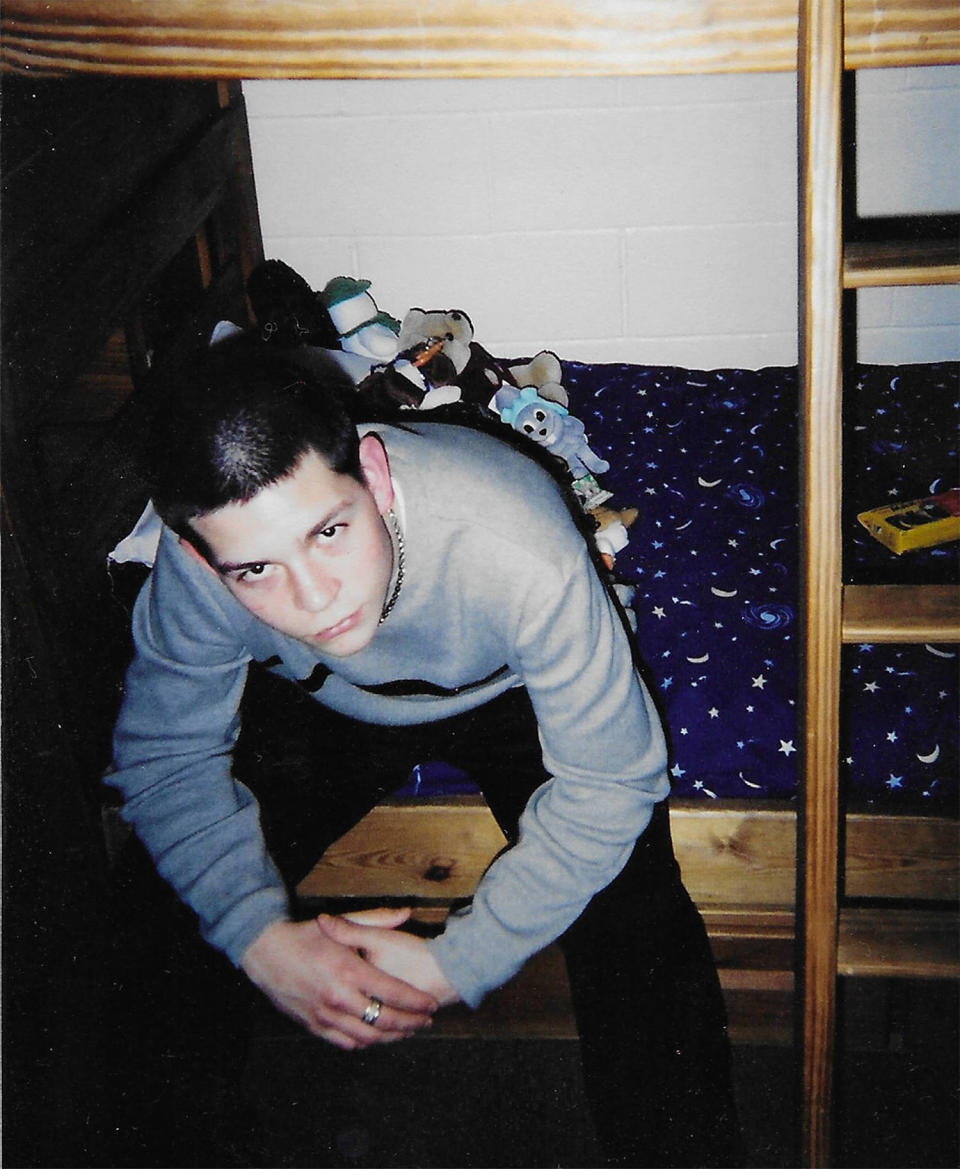

I became defiant, running away when I found my chances. I ran away from DeSisto three times. The first two times, I was dragged back in a van. My final time, I was determined.

I escaped out of the Farm’s bathroom window. It was the only window that opened in the building. I had convinced the sole staff member to let me close the bathroom door for privacy. As I crawled into the window, he opened the door and yelled. I looked back at him and jumped. I knew at that point I had to just keep running.

After three years at DeSisto, I ran off into the swampy woods beyond the school, my feet sinking into the mud as I chased after my freedom with little foresight about my next move. Nobody came far enough into the wetlands to find me. Since I was 18 when I ran, once I was off campus, they could not legally bring me back.

I hiked the main road into town, putting together a plan to ask for some quarters to make a call. I was able to contact an old employee named Luis, whom some of the students trusted. He agreed to pick me up at the Piggly Wiggly in town.

There’s a reason I didn’t call my parents. By the time I left, if there was one lesson I’d learned from my time at DeSisto, it was that I could not rely on them to understand. In “The Program,” Kubler explains her parents were conditioned into believing that anything negative she said about the program was a lie or manipulation. DeSisto’s parents were instructed on this, too. They were advised that if they took in their children after they ran away, their children would be expelled, and years of education — and tuition — would become null and void.

By the time I got to the parking lot, it was dark. I walked over to a trash can and found it had just been emptied and lined with a new bag, which I took and used as a sleeping bag. I spent my first night outside of DeSisto in almost three years, lying on a bench outside, hungry, thirsty and shivering.

So much had happened and changed since I was 15 years old and soaking in the clawfoot tub with a Snickers bar.

Founder Michael DeSisto died in 2003 and DeSisto itself shut down in 2004 after controversies, including fights with the state of Massachusetts over licensing and allegations of child abuse. The Massachusetts Office of Child Care Services wrote, in a complaint, the school “denies students basic human rights” through practices like strip searches and farming students.

In 2004, DeSisto was under state investigation for incidents including a staffer waiting more than 90 minutes to take a student to the hospital after she self-harmed and swallowed two razor blades, the Boston Globe reported at the time.

“We admit our response was less than adequate and we’ve dealt with it,” Frank McNear, the school’s director at the time, said at the time. “You’ve got a lot of kids with a lot of pathologies here. I won’t tell you we’re a perfect school, but we’re totally committed to addressing problems as they surface.”

I’ve lived so many different lives since leaving. I’ve spent most of my life trying to push the negative parts of my past aside and focus on moving forward.

But every once in a while, something pulls me back — terminology, a headline, and more recently, “The Program.” I’ve been told before that I display post-traumatic stress symptoms, but it wasn’t until recently that I connected my feelings, my anger, to my school experience.

I’ve started opening up about my feelings more in the years since I escaped, especially as other lawsuits against the school validate that I wasn’t just a teenager, dramatizing my experience to make my parents feel guilty. My concerns were valid. I've felt less alone.

Survivors, if you can call us that, tend to discuss it amongst themselves, but I never really shared the full extent with anyone outside of them, not even my wife.

Our community of former DeSisto students is more than plagued by the memories of what happened there. Too often, we are confronted by the concerning reality that DeSisto’s body of alumni is vulnerable to death by suicide. The death announcements of a familiar name or face continue to haunt us.

During COVID, I learned that my friend Sarah died by suicide. I still tear up when I think of her. She was a talented performer and an amazing illustrator. A group of us used to hang out after “meal jobs” were done, when we cleaned the dining room, washed the dishes and prepared for the next meal. She was full of life and laughter but struggled with self-esteem and low self worth. She was a really special and kind person.

In the decades after we left DeSisto, it’s my understanding that her struggle went on for years. She deserved better.

I can’t entirely say that my experience at DeSisto was all bad. The truth is, I really began my journey to adulthood there. I learned self-awareness, self-worth and work ethic. I learned responsibility for my actions as well as my emotions. But I also learned distrust, abandonment and the level at which my own vulnerability could be exploited.

But I can say that much of my life in the years since has felt like climbing out of a massive hole.

After a failed attempt at community college and many odd jobs, I found direction and put all my energy into graduating from art school. My relationship with my mom and stepdad was OK at this point, but everything was still unresolved. My biological dad and I spoke once every five years at this point.

I continued to struggle, but eventually, in my 20s, I got my bachelor’s. I learned to understand my parents more. I married and had two beautiful twin boys. I got divorced, I got sober and eventually, I found myself escaped from the black and away from the threat of tipping over the edge. In 2014, I learned what it was to have a real relationship with trust, love and respect. Seven years later, we welcomed our beautiful boy.

I look at my sons and see how different they are from one another — and see the similarities they have with the old me.

I worry about whether they will struggle the same ways I did, and what will I do — what can I do — if they do? Truth is, I could never imagine sending my kids away and frankly, I never would. But I also don’t have a clue what I could do as an alternative. If DeSisto was the wrong choice, what would the right one have been? Was I in that situation as a teen due to nurture or nature?

I appreciate my sons’ personalities and struggles. I so desperately want to make sure that they never feel alone. They are the faces I force my brain to sharpen in on of when the memories of DeSisto begin to creep in, threatening to blur my current reality. They are the ones that bring me back to my life.

This article was originally published on TODAY.com