Ralph Lauren Talks Family, Fashion, and His Global Empire

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Ralph Lauren walked into the living room of his house in Montauk, slightly exhausted and sweaty. “I hope you don’t mind,” he said, “but could you wait just a few minutes for me to take a shower? I’ve been practicing baseball with my trainer.”

He was preparing, he explained, for an event at Yankee Stadium in late September at which he was scheduled to throw out the first pitch, one of the many public commemorations of the 50th anniversary of his business. (The events began on September 7 with a blockbuster fashion show and black tie dinner at Bethesda Fountain in Central Park.) At 78 he was a bit unsure of his pitching arm, and while he had no illusions that he would be confused with C.C. Sabathia, he wanted to be sure not to embarrass himself.

It was typical of Ralph Lauren, who approaches every task with a sincerity and forthrightness that set him apart from almost everyone else in the ruthlessly cynical, competitive world of fashion. He was thrilled at the notion of throwing out a ceremonial first pitch at Yankee Stadium—after all, he grew up in the Bronx, not far away—but he saw the invitation not just as an acknowledgment of his success but as a challenge to do the right thing.

He could have gotten away with a quick toss, but that would suggest that he did not take the event seriously. And so he practiced. His logic tells you all you need to know about the man. He cares about certain things, and he wants to do them right, whether or not anyone appreciates the effort behind them. He has built one of the most recognizable brands in the world—and one of the few considered American emblems, like Coca-Cola or Tiffany & Co.

As his peers in New York retire or leave the main stage, Ralph Lauren looms large. He is the creative head of a multibillion-dollar business, designing new lines of clothing and overseeing design-oriented enterprises that range from retail stores to restaurants to home furnishings, all based on what you might call idealized images of American style, from preppy fashion to Art Deco glamour to Adirondack ease.

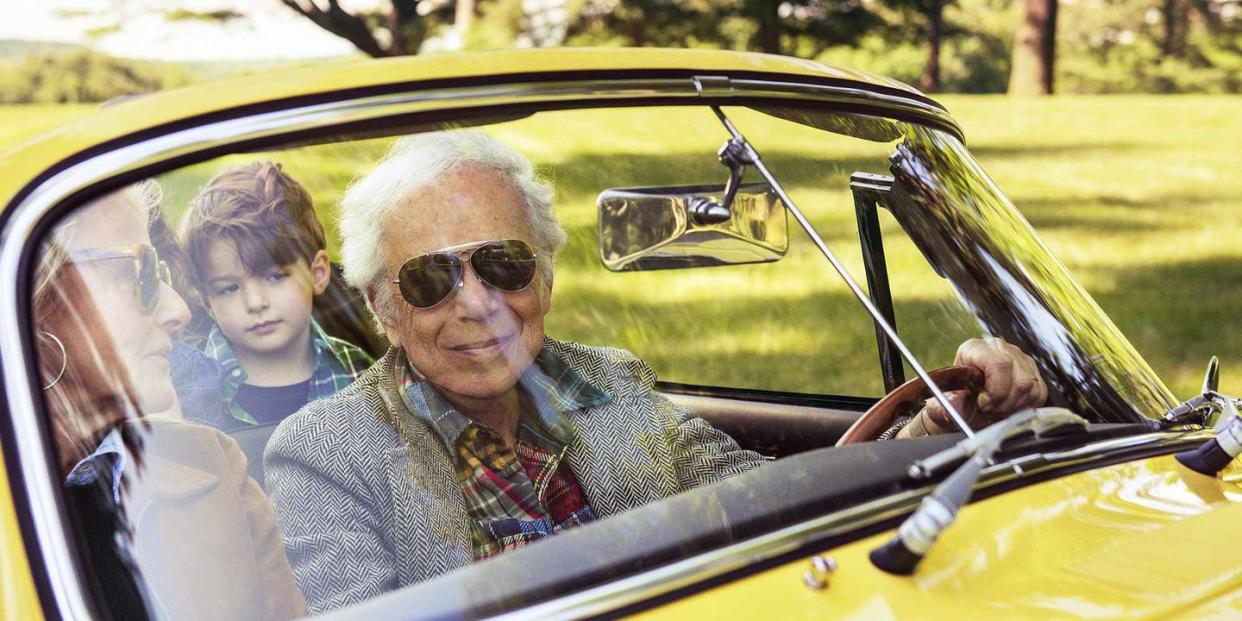

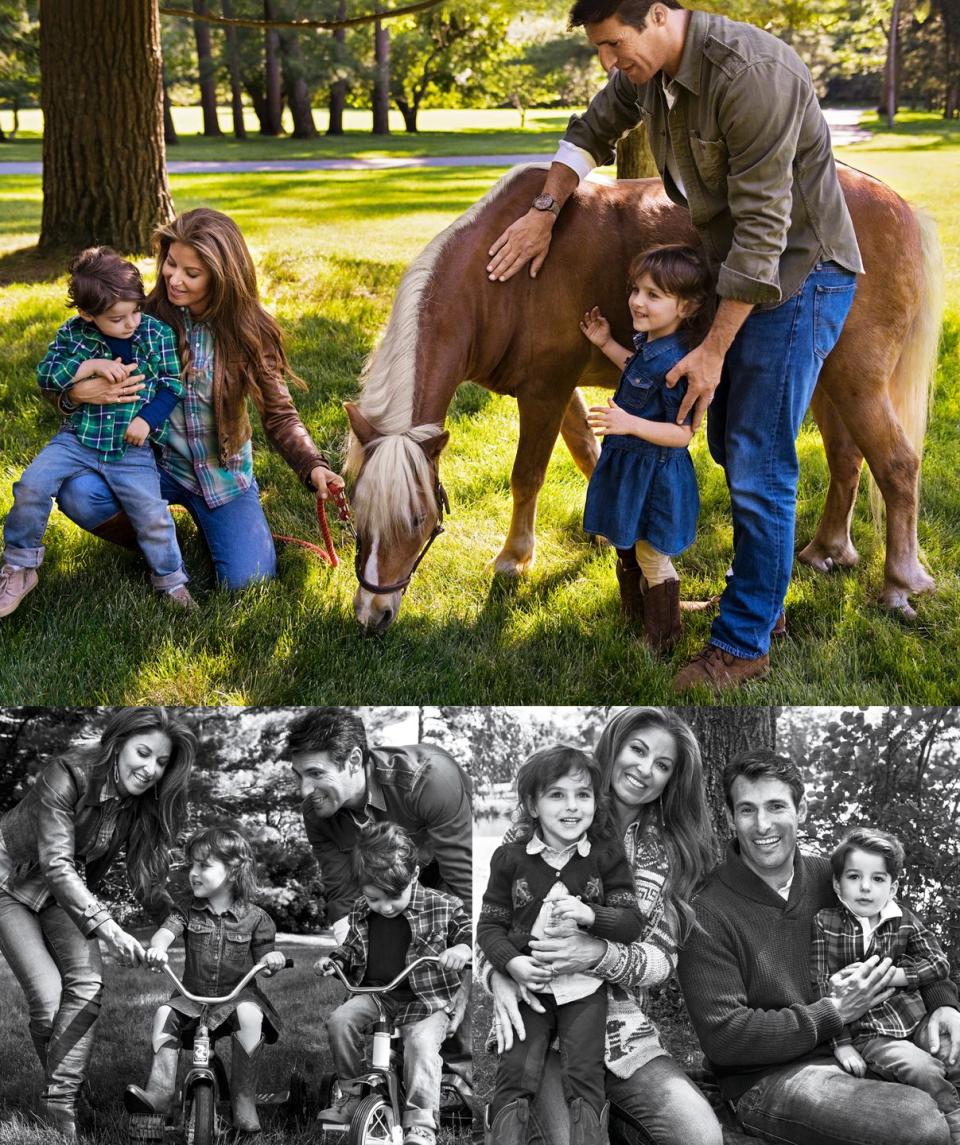

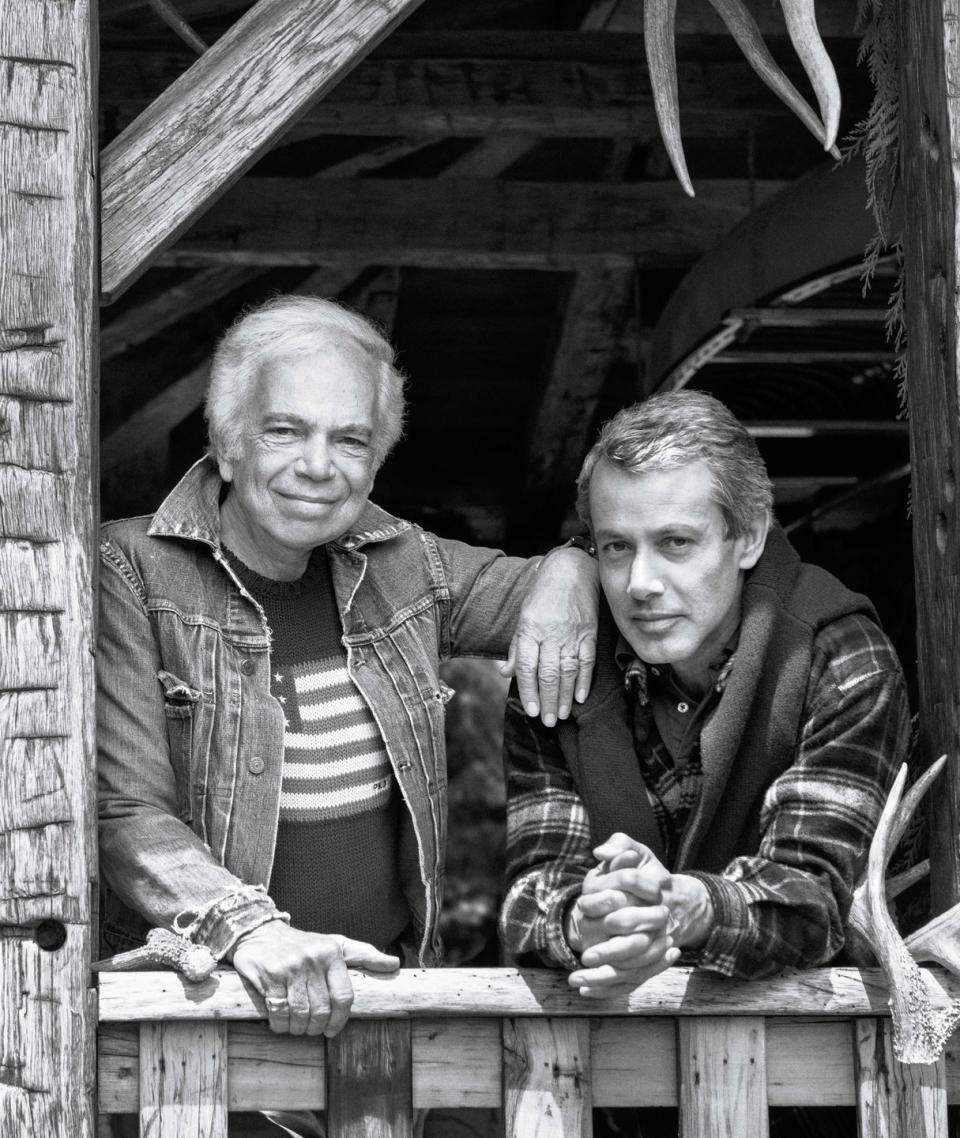

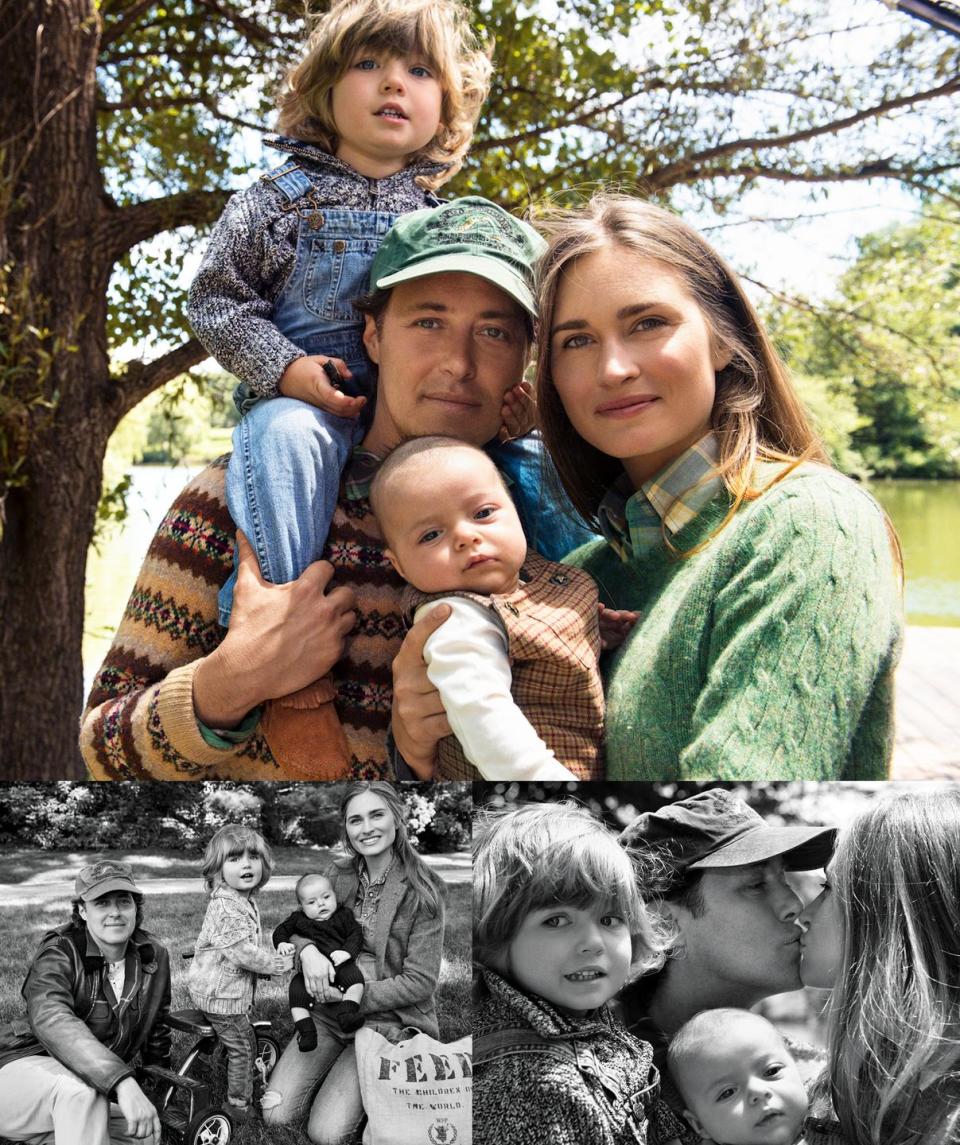

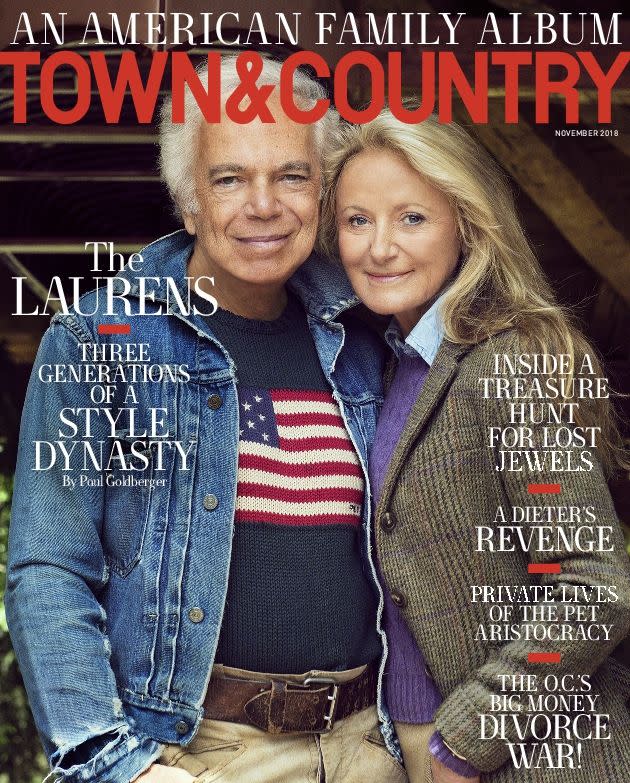

Lauren is also paterfamilias of a unit that is part and parcel of his legacy. His wife Ricky and his three children, Andrew, David, and Dylan, have long appeared in his advertising, and David, 48, is now chief innovation officer and vice chairman of the Ralph Lauren Corporation. At the 50th anniversary fashion show in Central Park, amid such luminaries as Oprah Winfrey and Hillary Clinton, all the Laurens stood up when he took his bows, as they do at every one of his shows.

They have been a constant, a pillar that has kept Ralph focused despite the inevitable curveballs: “You make mistakes, you get up. I’m a big Rocky fan,” he told me. Now, with new CEO Patrice Louvet in place and earnings on the upswing, Lauren, who remains chairman and chief creative officer, enters the second half-century of his business with the wind at his back.

A few minutes later, after showering, Lauren returned, dressed in shorts and a striped shirt, and we sat down to talk in the living room. He and Ricky purchased the Montauk house in 1983; it is part of a quintet of homes Lauren owns, all of which he has crafted into perfect Ralph Lauren environments: a sprawling estate in Bedford, New York, where the photos for this story were taken; a ranch in Colorado; a beachfront house in Jamaica with a cottage that once belonged to William Paley; and an apartment on Fifth Avenue.

The Montauk place is both elegant and comfortable at the same time—comfortable in part because it is not so elegant as to be intimidating. The wood-paneled room overlooking the ocean has a large fireplace, a sisal rug, a couple of Eileen Gray glass tables, a sprawling white sofa, and a mirror that reflects the view of the surf. A big coffee table in the center has piles of art and architecture books, an old copy of a magazine with David on the cover, and the catalog for an upcoming auction of vintage automobiles in Pebble Beach.

The mix makes sense: serious books on high design, popular culture, and family memorabilia sharing the space in a way that looks too natural to be curated, too ordered to be entirely random. In other words, pure Ralph Lauren.

Paul Goldberger: There is an easy quality to this room, a sense that everything is just right—not too much, not too little, not too fancy, not too plain.

Ralph Lauren: I like understatement, and I like comfortable places. I want someone to come in and feel good. It was not easy doing this room, because it takes a lot of effort to make something feel relaxed.

PG: I once heard someone say it takes a lot of reality to make a fantasy.

RL: Exactly. A lot of hard work is hidden behind nice things. You know, I have never believed in fashion victims, and the same idea applies to design. People want to be comfortable. It’s not that I’ve created the best furniture in the world, but I think I have the ability to link it all together and make a place feel like you want to be in it.

PG: I guess you could say that you’re trying to make things feel familiar and special at the same time. Does that apply to the clothing you do as well as the spaces you design?

RL: The environment always matters. I have always wanted to build a world and make everything feel a part of the same vision. It’s about the feeling that certain things are right, that a particular version is better. People see the difference. I remember walking into a department store with Ricky years ago and seeing flowered sheets and saying, “I’m not sleeping on that.” So I started my home furnishings line. My first sheets had button-downs like oxford collar shirts.

PG: You have always made a point of saying you design to your own taste, not to some notion of what can be marketed, right?

RL: I never did focus groups. I went and did the things I loved to do. It was instinctual, and very passionate. When I started out, my goal was to express myself. I designed these ties and then went around in my bomber jacket and jeans. Bloomingdale’s said they liked them, but they wanted me to make them narrower and put a Bloomingdale’s label in them, and I said I couldn’t do that. Six months later they came back to me and said, “Okay, we’ll give you your own rack, and they can carry your own label.” And after that I started doing shirts and went on from there. It wasn’t about fashion, it was about what I wanted. And then, all of a sudden, I realized I was building a world, telling a story about the things that I loved.

PG: But it’s not the story of your own past—it’s the story of your fantasies, which have been amazingly consistent over 50 years.

RL: Yes, but good taste alone is not going to build a company that lasts for 50 years. You know, good taste can be boring taste, and classics can be uninteresting. If all I had was good taste, people would say this is just an old man designing clothes. I try to make things that are fresh and different, even if they are inspired by classic things. I want the audience to be the chairman of the board, but also the boys in Harlem, the kids who want sexier clothing. Why does Cary Grant always seem fresh, or Frank Sinatra, while someone else seems tired? There is always a spin, something new—as well as the feeling that Sinatra is singing only to you. It is stimulating in the same way I’ve always felt Porsches and Ferraris are stimulating.

PG: Your fondness for Porsches and Ferraris, and for Jeeps and Ford pickups, seems analogous to the range of clothing that you design.

RL: My philosophy has always been that I can sell chinos and T-shirts and $5,000 gowns—they just have to be the best of what they are.

PG: You’re one of the few people whose name has become an adjective. But to call something “very Ralph Lauren” is, to some people, a way of saying it’s maybe a little too perfect, a little too neat, more of a stage set than real, that maybe it has a degree of artifice.

RL: It’s what’s true to me. When I did my restaurant in New York, I made the restaurant I wanted myself, with the food I wanted. My personal life has always been the same as the world I’ve created. I think it’s more that I try to have the things I make not show all the effort, that I want them to look natural and easy. I remember watching Joe DiMaggio as a kid: It all looked so easy, so smooth—like Federer now. He doesn’t look like he’s killing himself. I want my clothes, my stores, everything I design to have that feeling of being natural and easy. And that takes effort, but you try not to have it show.

PG: The screening room that you added to this house seems to show that particularly well. It’s a relaxed room filled with black-and-white pictures of Hollywood stars, but it’s not an over-the-top pretend version of a movie palace. It’s more like Art Deco meets Big Sur.

RL: This was a garage, and we did it because I love movies and I love having my family around. We did it so our kids would come.

PG: And do they?

RL: Yes. Andrew is here this weekend. David and Dylan and their families come a lot.

PG: Hence the strollers I see in front of this door. Let’s go back to the public image of Ralph Lauren for a moment. How much do you think of Ralph Lauren as being a specifically American brand?

RL: When I started, I felt that America was too much about mass production, that what we made could be more special. Why should people go to Europe, to European brands, for good clothes? I wanted to show that we could do something American that was just as good. When I went to Russia to open a store in Moscow, I remember thinking, This is where my parents came from, and now I’m back here not just to open a store but to represent America, that Ralph Lauren is a big part of how they see America.

PG: I remember a great conversation you and I once had before an audience of fashion students at the Parsons School of Design, in which you talked about your background. You told them you were nervous before your first fashion show, and that for all the success you’ve achieved, you still worry.

RL: Well, now it’s my 50th anniversary and I’m still worried. I don’t take anything for granted. I do what I do, and I have an audience that I speak to, and I go for what I really believe, but I know not everybody thinks I’m great.

PG: You talked a moment ago about how important it is to get your whole family together, and how much you like it when your adult kids come to visit. How do you think about your family legacy? Does philanthropy play a part in this?

RL: I am very emotional about life and family—I’ve been married for 54 years. I’ve appreciated my life and my family, and I’ve been very lucky. So as far as philanthropy is concerned, I have never done anything for effect, only if I have been interested in it. I had a brain tumor 30 years ago, and after that I saw my friend Nina Hyde of the Washington Post, who had breast cancer. She wanted to start a center for women with cancer, and I said I would help her.

Then I thought we could do more, and I went to Memorial Sloan-Kettering, and a very dedicated doctor said they really needed help in Harlem, and we built a cancer center there. I’m not a doctor; I just wanted to do what I could to help. And I don’t think I’m finished. We have done other things, too. We supported the restoration of the American flag [the original Star-Spangled Banner that flew over Fort McHenry during the War of 1812], because America has been very good to me.

PG: It seems as if you seek a personal connection in your philanthropy.

RL: For me everything is personal. I realize that over the course of 50 years you could blow it or you could stand for something. I’ve worked hard, and I feel that I’ve made beauty, and I’ve made things that make people feel better. I don’t want to be remembered only for selling thousands of shirts.

This story appears in the November 2018 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like