Raising a Family of Criminals

A father refuses to give his children toys, won’t let them play sports and beats them but teaches his sons to steal, applauding as they graduate from petty thievery to stealing multiple tractor-trailers, all while they’re still legally minors. They turn the money they make over to him; he needs it because he refuses to work.

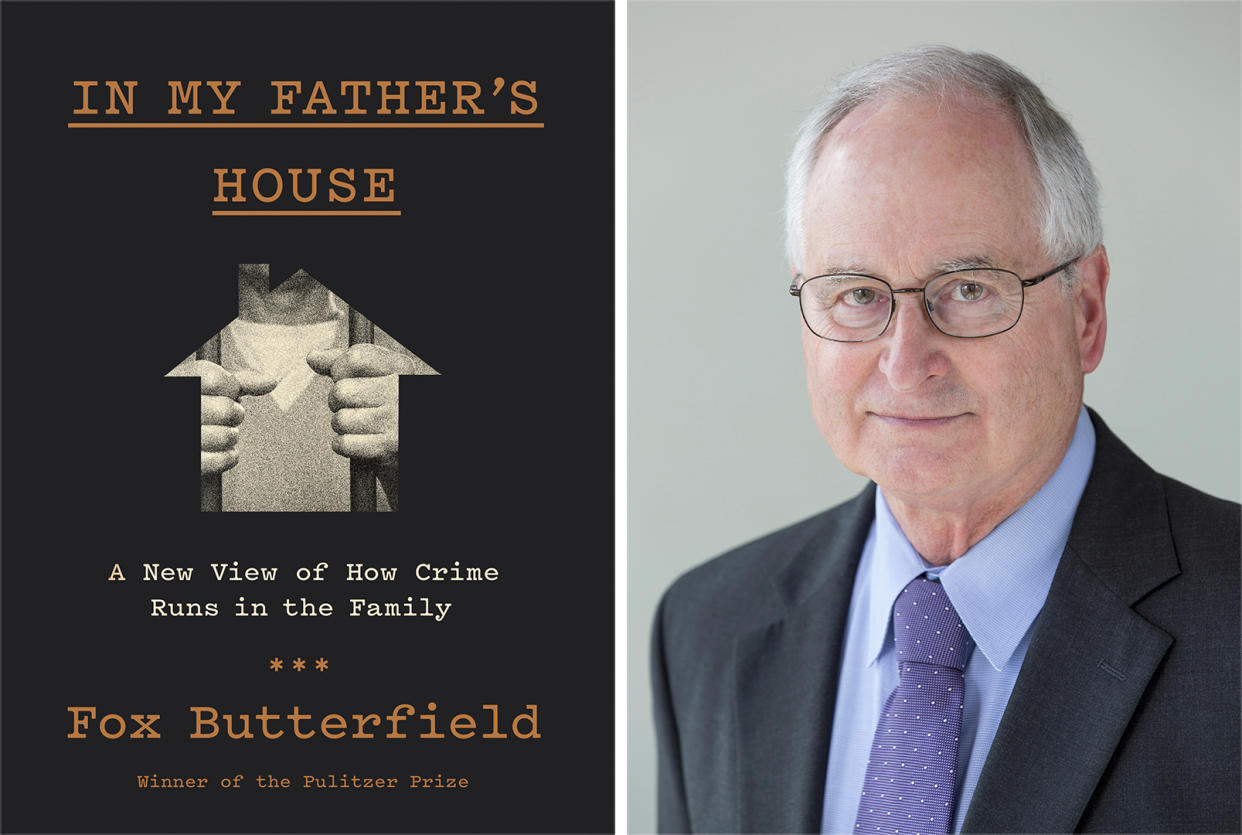

This parent considers attending school unnecessary, but insists that his progeny fight anyone who says a harsh word to them. That’s the way Rooster Bogle — the paterfamilias of a white clan known to the authorities in Oregon for the many crimes committed by its members — raised his children. Now journalist Fox Butterfield has written a book about the Bogle family, “In My Father’s House: A New View of How Crime Runs in the Family,” which is due out from Alfred A. Knopf on Oct. 10.

Butterfield, who was a longtime reporter and editor for The New York Times, has also written another book about a family, this one black, with many members who’ve done time. “All God’s Children: The Bosket Family and the American Tradition of Violence,” was published by Knopf in 1995. The Bosket family, originally from Edgefield, S.C., moved to Georgia and later to New York City. In “All God’s Children,” Butterfield took a deep dive into Southern history and traced some of the Boskets’ attitudes to the code of honor of the white antebellum South.

The writer notes that something that the Bosket and Bogle families have in common is that, whenever the major figures in each clan (such as Willie and Butch Bosket or Rooster and Tracey Bogle) were given chances to make choices, they made the wrong ones. “In general, it’s disturbing and depressing to find a family making the wrong decisions all the time,” he says.

Several years after “All God’s Children” came out, Butterfield decided that he wanted to write a book about a white family with many criminal members. His friend Steve Ickes, then assistant director of the Oregon Department of Corrections, told him about the Bogle family. At the time, Ickes was under the impression that six members of the family had been in prison.

In fact, as Butterfield was to learn, 60 of them had been incarcerated; he includes a record of their crimes in a section of the book called “A Family Guide.” The infractions range from burglary to murder. Butterfield writes that this number of prison sentences might seem to be outlandish, something out of Ripley’s Believe It or Not, but it isn’t. Instead, he goes on to write, it’s “a dramatic example of findings by criminologists from around the United States and other countries, that as little as 5 percent of all families account for half of all crime, and that 10 percent of families account for two-thirds of all crime.”

It took Butterfield some time to win over Bogle family members and to get them to agree to speak with him. The book was also delayed by an unexpected event in his personal life: the death of his son Sam, a recent college graduate, in 2013. “In My Father’s House” is dedicated to him. Butterfield and his wife, journalist Elizabeth Mehren, moved from Hingham, Mass., to Portland, Ore., partly as a result of this.

However, Butterfield says Linda Bogle, the second of family patriarch Rooster Bogle’s two wives, “in some way wanted her life memorialized” and she helped him to track down her relatives. In the end, he did thousands of hours of interviews across the country.

The Bogles’ stories include crimes transformed into fun family outings, among them a raid the entire family made on a famous salmon hatchery at Bonneville Dam. Originally from Amarillo, Tex., Rooster moved his clan to Oregon in the early Sixties because, after he had committed a series of crimes and been imprisoned, local law enforcement was watching him too closely. Rooster had been the favorite, overindulged child of a seemingly amoral mother, Elvie Bogle, who was a carny and a con artist, and her husband Louis, a moonshiner. The mothers of each had been committed to and died in a Texas mental hospital, suggesting a strain of mental illness that also seems to run through the family. Elvie and Louis moved to Oregon when Rooster relocated there.

Rooster lived with his then-wife and his mistress, Kathy and Linda, at the same time and had children by each of them. Rooster informed his sons that in due course, they would be going to prison. He showed them the Oregon State Correctional Institution in Salem, where, he said they would eventually be incarcerated. Some were. They were also, at an early age, initiated into sexual activity by him with prostitutes he had chosen.

One member of the family, Kathy’s sister Bertha Wilson, or Bert, who served a single prison sentence then went straight, described her relatives’ behavior this way: “It’s the way we were raised. We imitated what we saw our families doing. So it was all we knew how to do, and therefore it was the easy thing to do. We didn’t have the skills or education to make other choices or get a job.’”

As for solutions to families with this type of ingrained culture of committing crimes, Butterfield mentions several ways of dealing with it. Geography can help. He observes that the city of Baltimore has been trying to relocate inmates who are due to get out of prison away from the part of the city they hail from by offering to pay their rent in other areas — such as the suburbs. The writer points out that the inmates from New Orleans who were released from prison after Hurricane Katrina hit often had to go to places such as Texas, and that far fewer of those who relocated have reoffended.

One of the writer’s takeaways from spending a lot of time interviewing people in prison is that contact with family members who are incarcerated, long regarded as beneficial to inmates by government authorities, “tends to glamorize prison,” he says. “Kids grow up thinking that this is what they are supposed to do, go into the criminal justice system.”

He adds, “I really think if you’ve ever spent time in a visitors’ room at a prison, [you see that] people coming in are intrigued by the inmates and find them attractive and fascinating in some bizarre way.” Women who get involved with men who are incarcerated, he says, “think that the men are in love with them. I watched that happen in a number of prisons around the country.”

Related stories

Bob Woodward Won't Reassure Anyone About Trump

Donna Karan Critiques the Talent and Talks Sustainability at Parsons MFA 'Generation 7' Show

Get more from WWD: Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Newsletter