Racist, disgusting, lucrative: inside the hateful, empty world of NFT art

This art gallery looks like any other. It has white walls and bright lighting, and the works are evenly spaced on the walls. But those works are displayed from what look like flat-screen televisions, hung vertically, blaring the equivalent of a gif you might right-click-and-save from the internet.

Works such as these – or rather the Non-Fungible Tokens that “prove” ownership of them – have recently sold at Sotheby’s and Art Basel in Miami. With a trove of images of sneakers going for $3.1 million (£2.3 million), and a single grey pixel selling for $1.3 million (£1 million), the NFT fad has even Damien Hirst out there peddling his digital art.

The gallery I’m at, in Chicago, is called “imnotArt” – pronounced like “I’m Not Art”, get it? – and it’s the first NFT gallery of its kind. As I struggle to manage the QR codes besides each work, which promise “more information”, the gallery’s co-founder and CEO, Matthew Schapiro, bounds over to help. I ask about the name of the space, and he says, “It’s like ‘I’m Not Art’, you know?” I sigh and say yes, I get it, but what does it mean to “not be art”?

“It’s not art, but it’s more than art.” Schapiro points to a doodle on one of the screens, depicting Chicago, alive with movement and colour. What makes it “more than art”, he says, is that it can be customised “so the sun in the work sets when the sun in the real world [where you are] sets”. The colours of another piece, a set of black and white lines that move and converge like a computer screensaver, can be changed to fit your preferences or (one guesses) your décor.

It’s all a little disappointing, like the equivalent of the waving-flag gif that decorated DIY Angelfire websites in the 1990s: a real marker of the limitations of the moment. And until recently, the NFT scene had been populated by the outsiders of the art world: illustrators, street artists, muralists, skate-punk kids. But there has now been an influx of so-called “real” artists. By that, I simply mean people who have access to the traditional networks of art making and distribution, via the schools and galleries that the outsiders both seem to long for and reject in equal measure.

Imnotart, for instance, currently has a show called Souvenir with Brendan Fernandez, a professor of art history at Northwestern University, whose work has been shown at galleries and museums all over the world. Here he’s showing a series of screen-bound “masks”, taken from the Metropolitan Museum’s Africa collection, set against a confusing swirl of pulsating colours and patterns. In using imagery of shells and other objects that have been deployed by different cultures as forms of currency, I assume it’s making some statement about cryptocurrency – but the contrasting colors made me want to turn my head away.

The unpleasantness of the work is typical of NFT art in general. In March, “Beeple” (aka Mike Winkelmann) sold Everydays, a composite of digital work, for $69 million (£52 million) at auction; it contains images that are purposefully infantile, offensive, grotesque, misogynistic and racist. There’s a portrait of Hillary Clinton with a penis and a caption of an image of the Dalai Lama suggesting he should “finger-f---” a girl. Winkelmann seems especially fixated on Donald Trump’s naked body, building it out one roll of fat at a time.

The work is, I guess, partly satirical, but if so, it’s sub-newspaper cartoon. There’s no real emotional content. Ben Davis summarised Everydays for Artnet: “We’ve passed through a racial uprising and a reckoning with sexism, and the cultural project of the moment is… innovating new ways to worship decade-old, BroBible-level brain-farts?” But Beeple has already called a critic such as Davis a “fancy-dancy elite art homo”, and in one of the images contained within Everydays. The lack of aesthetic meaning is the point. It’s the equivalent of trying to argue with an online troll; they’ll always win because they don’t sincerely mean what they say, and having an opinion or feeling in response starts to feel like a mistake.

This is the artistic culture that NFT art has created. It wants to be sold at Christie’s, but at the same time it also wants to thumb its nose at the Establishment, which (one would assume) includes collectors. NFT artists want to hate art while declaring their own work to be art, much as fans and filmmakers of Marvel movies want acknowledgment that the franchises are true cinema, with a lot of the same resentments and hostilities. The film fans are desperate for Martin Scorsese’s approval of the thing they like because they want to legitimise their taste and culture, and they lash out bitterly when he tries to point out, gently, how silly and empty their project is. They hate the gatekeepers; they want the gatekeepers to lift the velvet rope for them.

In that way, the NFT artists might be provocative, but the only thing that distinguishes them from other contemporary artists is a lack of credentials and access. I don’t see much difference between the Armenian artist Narina Arakelian auctioning an egg from her ovary as an NFT, and the veteran conceptual artist Maurizio Cattelan taping a banana to a wall. The point is just to provoke. Not into action, nor into a new way of thinking: artists of this kind want you to feel bad or exasperated, so they can laugh at you for feeling that way.

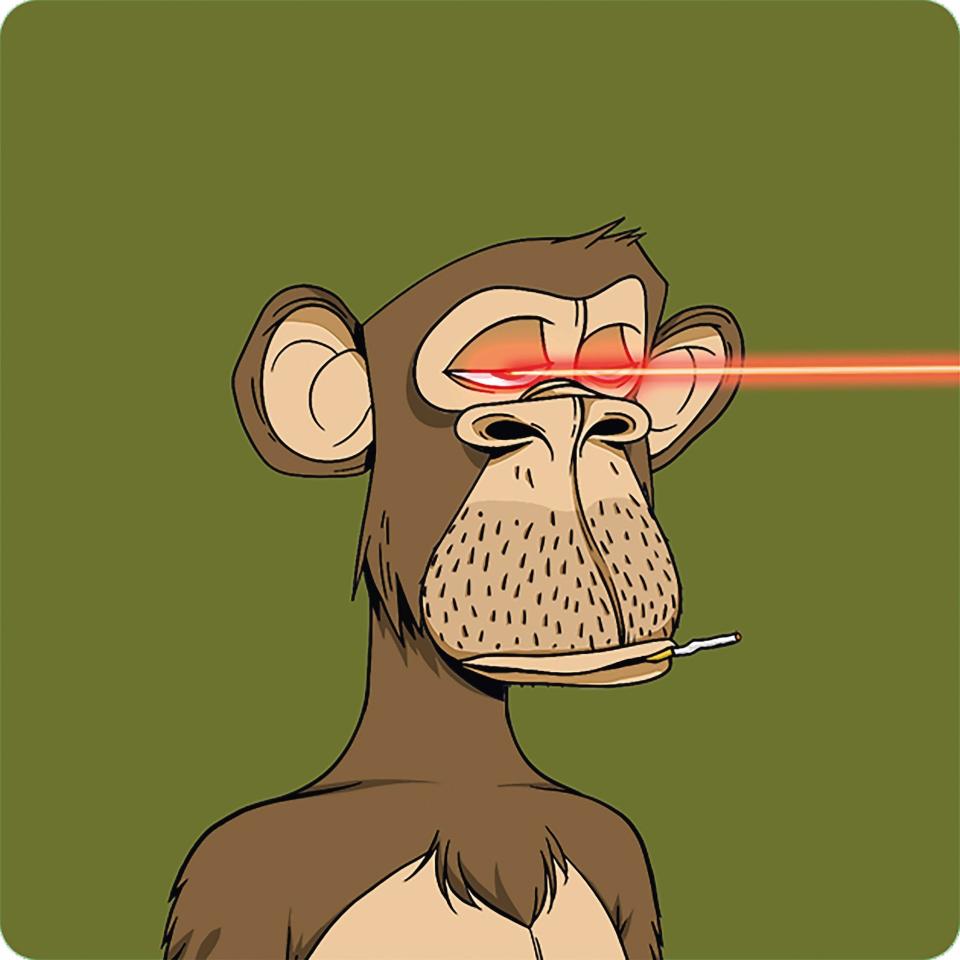

Let’s say you look at the Bored Ape Yacht Club NFTs that sell for millions (or the equivalent of millions in cryptocurrency, which at any moment could skyrocket into the billions or become worthless). You may then go on social media and write: “I don’t get it, it’s a drawing of an ape.” And it is: a drawing of an ape that looks like a streetwear logo, lazy and easily reproduced.

The general retort from people who buy ape NFTs, or save up for tokens depicting a policeman with the head of a Shiba Inu, will be: “LMAO, that’s not the point.” Many of these images can be issued in large batches with slight variations, which gives them a Beanie Baby appeal. This same-ness drives up their collectability and creates the same crazed energy as fans strive for completion. The people buying them are just like the majority of the art collectors who are all on Instagram Live at Art Basel this week: they’re desperately looking not for the next thing that will provoke a powerful emotion, but the next thing that will make them richer or increase their status or get them invited to a better party.

The scammers, however, are the real geniuses of the NFT moment. The format is inherently unstable and prone to breakdown, making it a perfect place for con artists. As Anil Dash, who co-created the first NFT as a way of proving copyright for artists who work on the internet, explained in The Atlantic, the NFT encodes a link or reference to the art, not the visual art itself:

Because of technical limits, records in most blockchains are too small to hold an entire image. Many people suggested… one could just include the web address of an image, or perhaps a mathematical compression of the work. Seven years later, all of today’s popular NFT platforms still use the same shortcut.

This means you could spend a million bucks on an ape, but if the hosting site for the image goes down, you could own the equivalent of a 404 Error Page.

All of this makes NFT art the perfect playground for fraudsters, who must know that most of the people spending millions on NFTs have no idea what they are buying. The art world is already a zone of consequence-free money laundering and tax evasion; NFTs just take that hustling into a more abstract place.

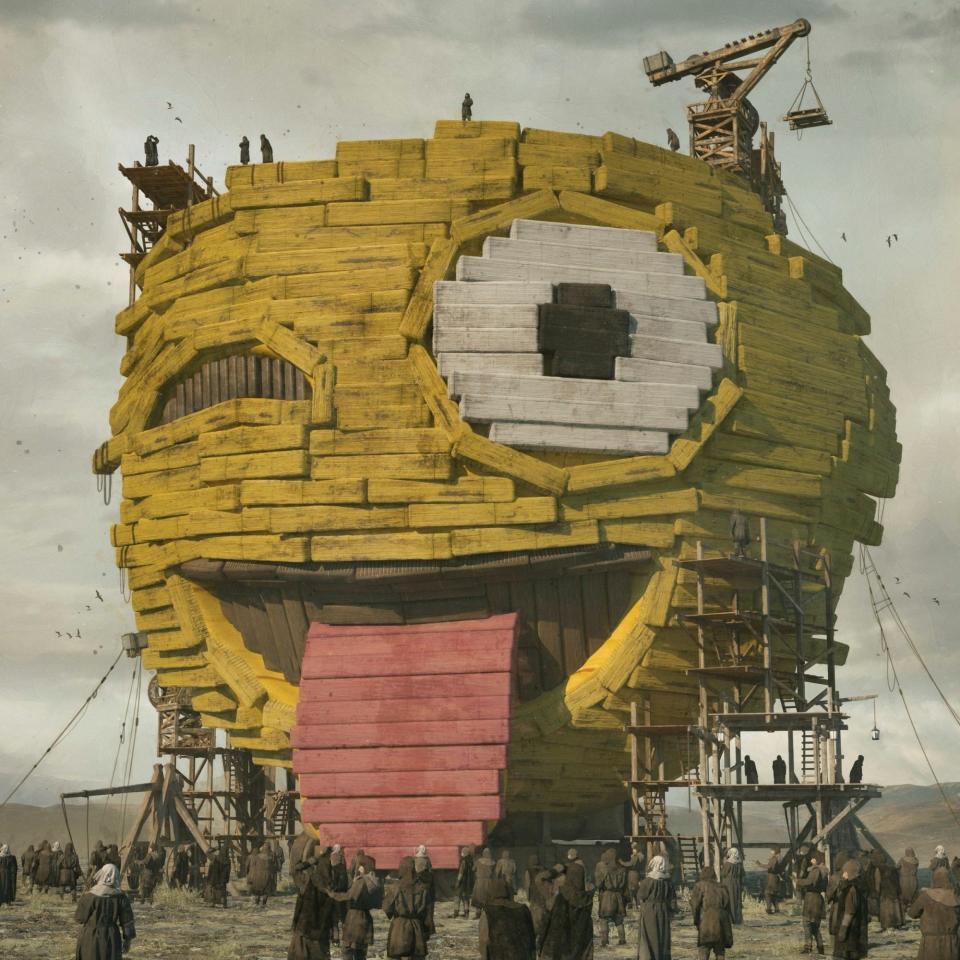

This, to my mind, makes the hero of the moment the 17-year-old artist who sold the promise of original NFT artwork for almost $140,000 (£106,000), then delivered a bunch of emojis instead. Much like Duchamp signing a urinal, the act of sending a crying-face emoji to someone who expects a blockchain token indicating his ownership of “quality art” – art that will appreciate in value and can be resold at a profit later – is a magical act of transformation and revelation. It reveals the emptiness of our cultural production, and of ourselves.