The Racism We Never Discussed

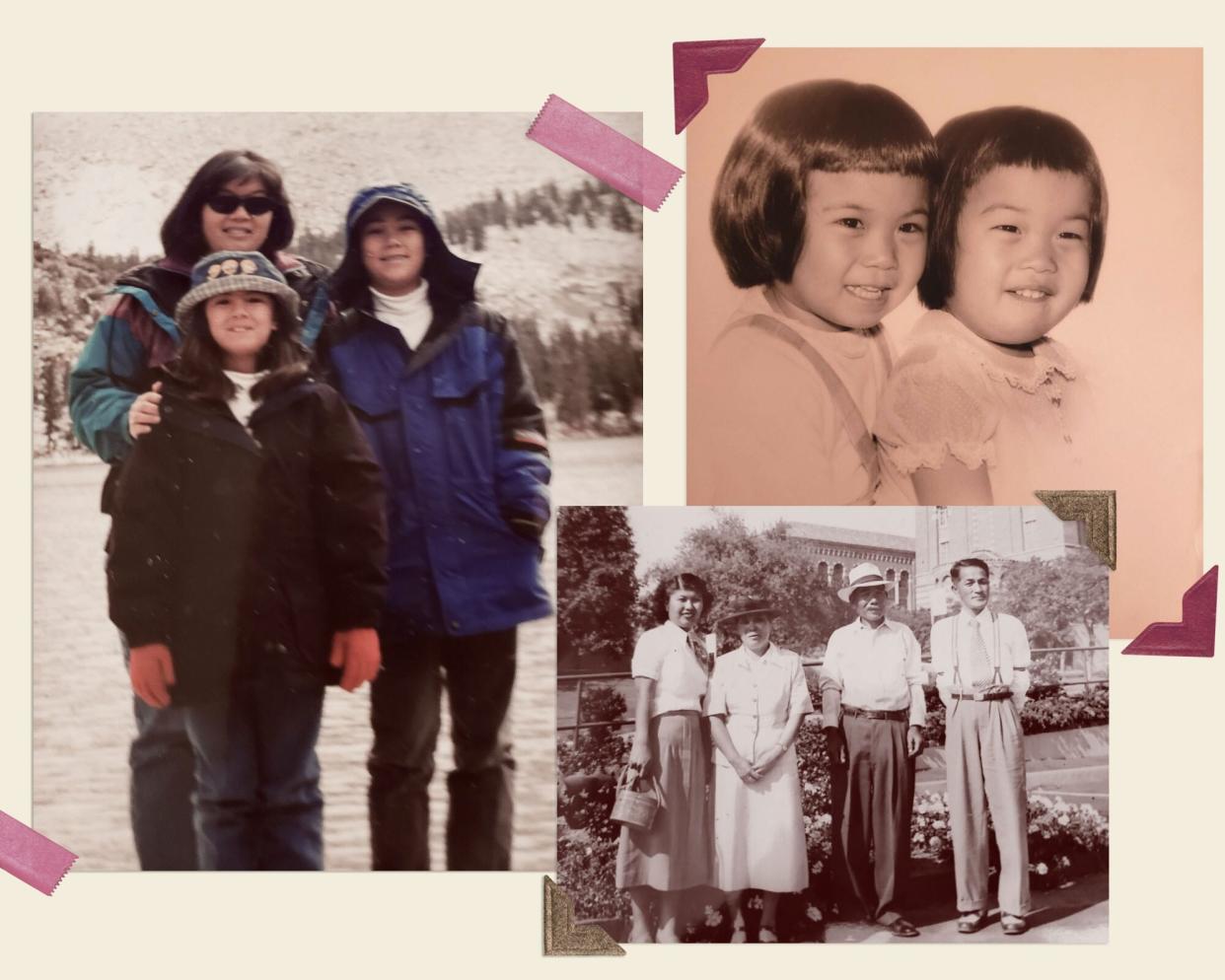

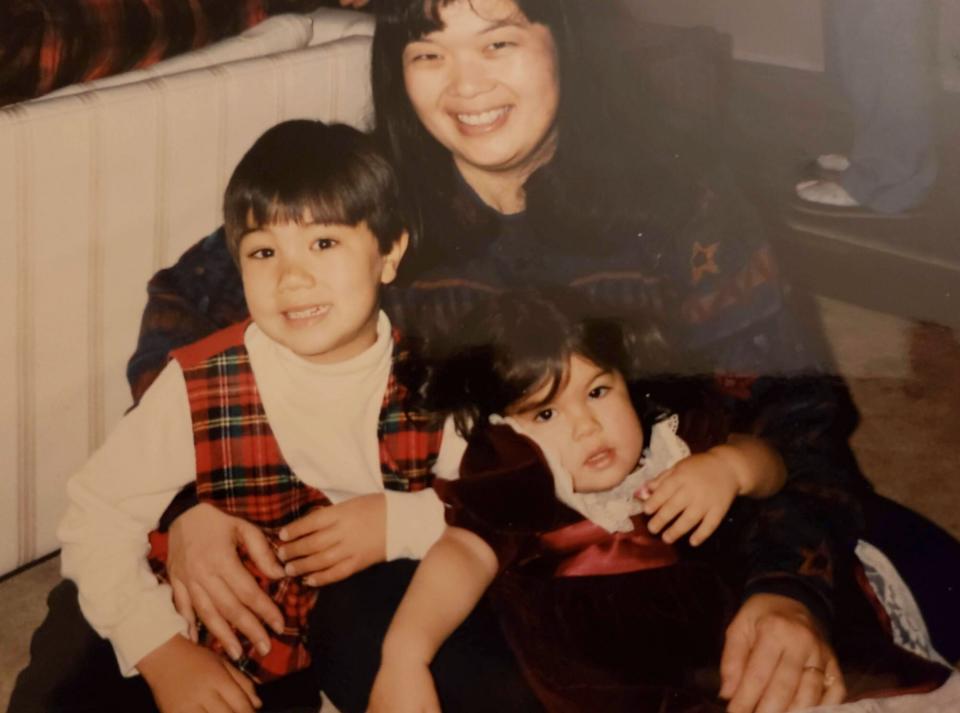

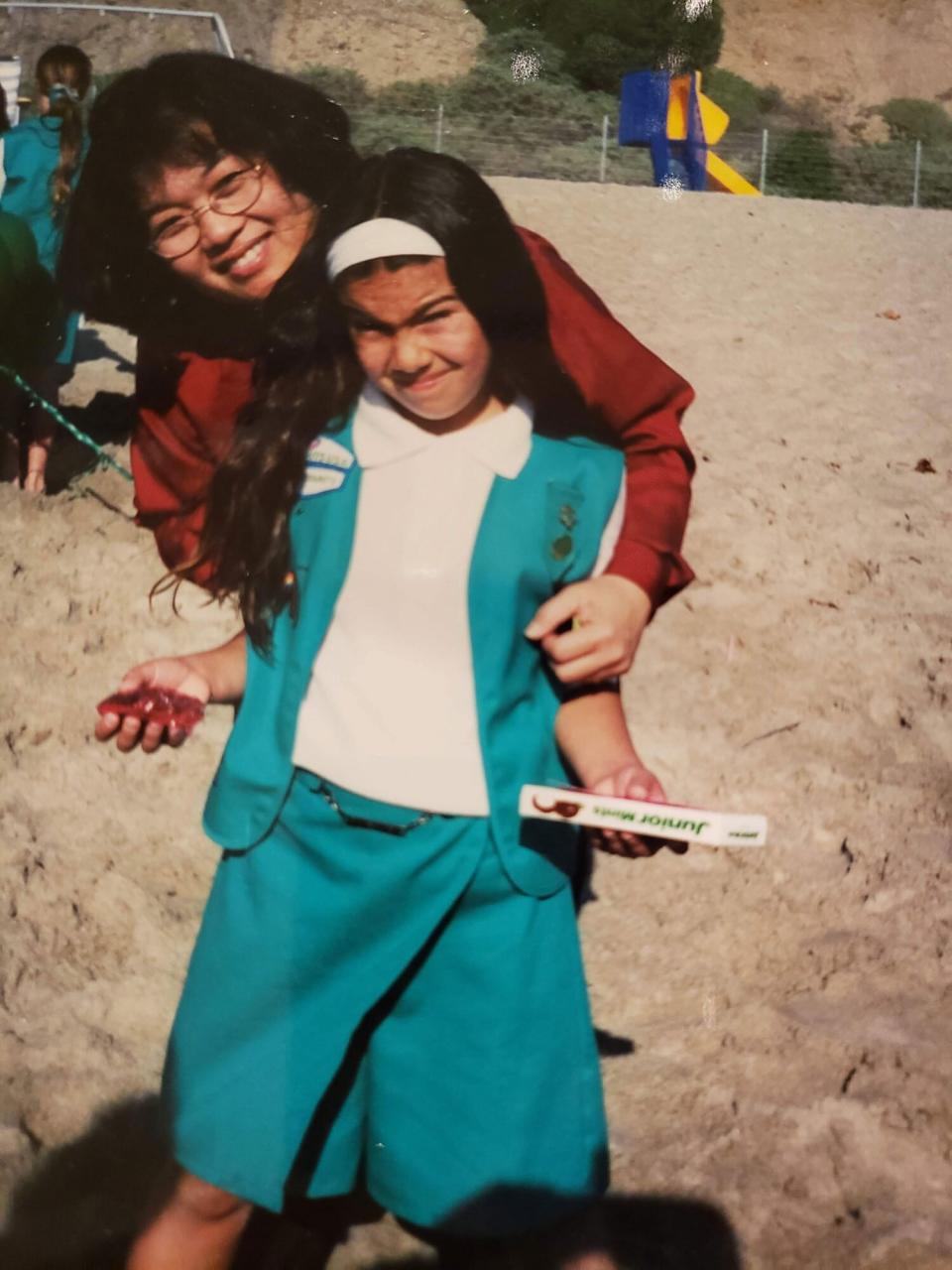

Kelly Chiello/InStyle.com; Photos: Courtesy, Getty Images

"Did your parents ever talk to you about being biracial?" my therapist asked me. We had been discussing my internalized racism, the conflict that had played out in my brain when I was young: I was not white enough. I was not Asian enough. I passed for neither race, and harbored a deep-seated fear that I didn't actually fit in with either side of my family. I was never comfortable.

"... No?" I replied, confused. I wondered, What would that conversation even look like?

My (white) dad is a firm believer in the idea that racism no longer exists. "I don't see color" is a line he touts often, as well as, "I mean, I married your mother." He never discussed race with my brother and me because he never saw a reason to. My mom's family was similarly indifferent, believing that for the most part, enough progress had been made for Asians in America. And anything else could be overcome by hard work.

Courtesy

And yet here we are, almost 30 years after I was born, facing the biggest reckoning around race in the U.S. since the Civil Rights Movement — which, as a reminder, was only 50 years ago. But while millions are marching for Black Lives Matter, there are others, like my dad, who are convinced that we "solved" racism already, and that most Americans, and more specifically, American institutions, aren't racist. That belief, and the silence that accompanies it, is dangerous.

Before the protests, racism against Asian Americans was spiking, too. Almost 80 years after the internment of Japanese Americans, we were being targeted, and the stereotypes (which have always taken two forms: "the model minority" — robotic, subdued, worker bees; and the "un-compassionate savages" — the dog eaters, the no-mercy barbarians and kamikaze pilots) all too easily flooded back into the American vernacular. As a community, we learned that racism was always there, just lurking under the surface. And we're the fools for acting surprised when we discovered these new attacks were just the tip of the big 'ol racist iceberg.

When I was growing up, my family didn't talk about racism we experienced daily, or the racism faced by other minorities — we just pretended it didn't exist. When we did discuss racism, it was in the past tense: our family was discriminated against then, but they are treated fairly now. Black people were forced to use different water fountains then, but we all use the same fountains now. Our silence can be attributed both to our Japanese American culture, as well as in the myth of the post-racial world. But it is undoubtedly a part of the cracked foundation of modern America, which gave way recently following the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Rayshard Brooks, and countless others at the hands of police. Because when we weren't talking about racism against ourselves, we also weren't talking about our experiences in the larger context of racism in America. We weren't talking about the anti-Black history of Asian Americans in Southern California, where I grew up. We weren't talking about the experience of Black Americans. And with our silence, we failed ourselves.

RELATED: An Explicit Guide to Being Anti-Racist

I only learned about the internment of Japanese immigrants and their American-born children (including my relatives) when my older brother wrote a history paper about it in high school, revealing to me that 120,000 people's basic rights were violated out of xenophobic fear. Later, I also wrote about the racism rampant in Southern California both before and after WWII. It was the first time I understood racism in America as something that wasn't limited to the experience of Black and brown people in our country's past. But the anti-Japanese propaganda, the internment — none of it felt personal to me. Even as I interviewed my grandpa as a primary source for my paper, he conveyed no trace of emotion or anger. "We were sent to Arkansas. We farmed. I was drafted into the military from camp. I came back." There was never animosity, no righteous anger toward Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who issued the executive order that stripped his family of their land and livelihoods. No resentment of the fact that after being sent thousands of miles away from the only place he knew as home — Southern California — he was drafted into the U.S. Army and sent to war in Europe. He might as well have been describing summer camp.

So, no, we didn't talk about my biracial heritage when I was young, or the brutal racism my grandparents faced. I believed my dad when he said that liberals were complaining about racism just to make white people feel bad. And I went on straightening the thick curls I inherited from my Japanese side every day and wishing my eyes would turn blue overnight.

Courtesy

A few months ago, when racist attacks against Asian Americans began to spike in light of the pandemic, I called my mom. We talked about the violence, about Donald Trump's blatantly racist language, about the subtext of an attack ad published by his reelection campaign insinuating that Joe Biden was in cahoots with the Chinese government because he was friendly with the former governor of Washington, Gary Locke, an Asian American man. She expressed shock. I expressed resignation of what I saw as inevitable.

"Haven't you experienced racism in your life?" I asked. She danced around an answer, clearly uncomfortable acknowledging that she has ever been on the receiving end of anything that could be labeled as such. "I don't know that [racism] has held me back," she said. "You know, life happens," she continued. "I think you can't let [racism] stop you from doing the things you want to do."

"Right," I countered, "but sometimes it does."

A pattern began to emerge as we spoke of my grandparents' experience in this country, as well as my mom's own childhood: No one in my Japanese-American family spoke about racism. Not even as our experiences with it evolved over four generations of living here. It wasn't so much a refusal to speak about the suffering, so much as a denial of it. But racism was still there and eating away at the youngest generations: All of us Yonsei, or fourth generation Japanese Americans, my brother and cousins, had no way to explain how we felt when kids would tug at their eyes, singing "Chinese! Japanese! Siamese!" So we repressed our anger and smiled because the adults in our life told us it was "just a joke." My mom says her parents "didn't really talk about" racist incidents they experienced in Southern California, "because … you don't. You just work really hard, you think that you're going to get ahead, and people will recognize that."

And there was even less talk of their experience in the internment camps, which my mom chalks up to a generational mindset. "[My parents] just talked about it as it was something that was," she says, because "they were Nisei," or second generation Japanese Americans. She says they were happy when, in 1988, President Ronald Reagan issued a formal apology on behalf of the United States government and issued reparations to survivors. "I think that we're lucky that that happened." Not talking about it, though, meant they weren't talking about how nothing resembling reparations has happened for Black Americans. It still hasn't, to this day.

My mother was proud of the strength her family showed in overcoming the discrimination they faced, and though she grew up more culturally American than not, says "I liked being Japanese. I never wanted to be white. I wanted, I think, to not have being seen as Asian be a detriment." Like my dad, she spent her youth believing that she existed in a post-racial world. She straightened her thick, unruly waves, but unlike me, she did it to fit what she thought a proper Asian woman should look like. Only in the past few years, as she's begun paying more attention to the dialogue around racism, has she looked back and identified some encounters in her life as racist, from the taunting "dirty Japanese" rhyme in her mostly white elementary school to being overlooked at a job, and told she would never be a leader because of traits chalked up to "cultural differences."

Even with all that hindsight, she was still nervous about sharing her stories with me. She worried her pain was nothing compared to what other minority groups have faced in this country, and she'd be seen as ungrateful for her success, or trying to excuse her own shortcomings. As a young adult, even I questioned whether my family's experiences with racism were that bad — a form of gaslighting from both within and outside of my family.

Courtesy

"I gave a speech on the internment, and I had said how bad it was for all of these Japanese American citizens who had gone into camp," my mom told me, recalling a college communications course. "And that was a little bit eye opening to me, because [when] people gave feedback, a lot of it said, 'Well, it seemed to be OK, because you never knew who was going to be a traitor.' I was surprised that people said, 'Well, it was OK to put Japanese Americans in internment camps to prevent something really bad.'"

As she told me the story, I thought of my eighth grade history teacher who told me I shouldn't use the word "camps" to describe the Japanese American experience in places like Topaz in Utah, Rohwer in Arkansas, and Manzanar in the remote California desert, because it "wasn't actually that bad." I thought of my Italian great-grandparents on my dad's side, who immigrated to the U.S. in the same decade as my Japanese ancestors, and whose businesses carried on in California as Mussolini joined forces with Hitler. I think of the people on crowded subways who'd refuse to sit next to an Asian American person this spring, but not think twice about squeezing a little closer to the white man in the business suit with a suitcase tag from JFK. I think about the impact of the virus on New York City's Chinatown, even though it is now believed most infections in the United States arrived from Europe.

My brother and I, like many people our age, became keenly aware of the racism we encountered only as we entered adulthood and left our small hometown behind. As kids, we didn't see an "us" group in our predominantly white and Latinx school. We didn't see our desire to be perceived as "more white" in order to fit in as internalized racism. Because our parents never talked to us about race, they never told us that white is not "better." My brother and I never spoke of our shared insecurity — or that he had secretly envied me for looking "less Asian" — because we both believed that somehow, if we tried harder, we could just change ourselves a little bit, and then fit in. We believed that all of the insecurity we felt for existing in our own skin was something we made up in our heads "because racism doesn't exist anymore."

RELATED: Asian American Women Must Stand with the Black Lives Matter Movement

In the context of heightened racism against Asian Americans in 2020, we realized the source of our social anxiety: Our country did have a history of racism against Japanese Americans. Our country did have a history of racism toward the Latinx people we were so often mistaken for, and it was this racism that often resulted in more blatant displays of hatred: A soda cup thrown at my brother's head as he walked down the street; a friend's father who begrudgingly drove me home from soccer practice while making snide comments about who he assumed my dad to be — an illegal "alien" working as a gardener. (The guilt of responding, "I'm actually not Latina," is fodder for another essay.) Those inklings we had about being treated differently because of the way we looked were not symptoms of hysteria. They were valid.

My mom, who is only now coming to terms with the microaggressions she faced, explained the dichotomous experience of being Asian in America like so: Though we have been discriminated against, denied citizenship, and depicted by Dr. Seuss himself as soldiers ready to betray America at any turn, we have not experienced the levels of racism that Black and brown people continue to face daily. Though we were put in camps, Japanese Americans were not exterminated like the Jews in Europe. And yet, at the same time, how bad do our experiences have to get before we say something? Before we talk openly about it among our families, how many more hate crimes need to be committed for it to count?

Until we talk about our experiences, we can't fully comprehend the gravity and the context of those who have it worse. Our power as allies isn't in gaslighting ourselves into believing we're just fine, it's in joining our pain to others', acknowledging it all out in the open, and saying none of it was ever OK.