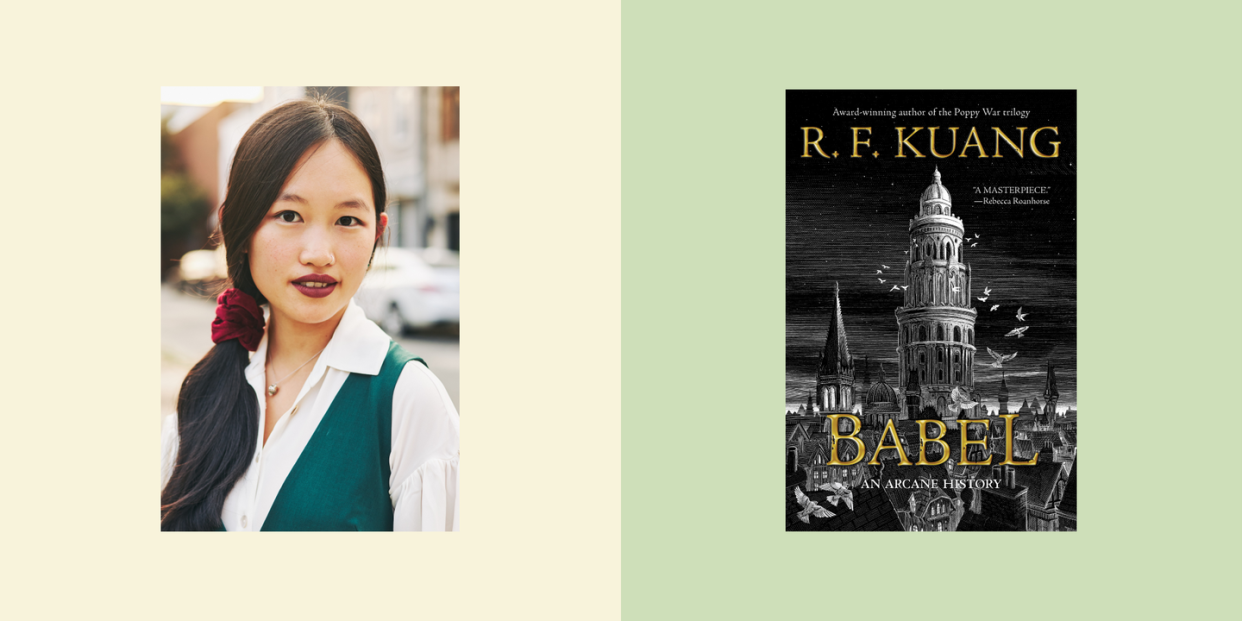

R.F. Kuang’s New Book, “Babel,” Decolonizes Dark Academia

Babel, or The Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators' Revolution is a fantastical takedown of 19th-century imperialism that’s as meaty as its title. R.F. Kuang proved her prowess at blending history and magic with her debut series, The Poppy War, and she's done it once again in this sweeping novel that blends historical fantasy and dark academia. So-called works of "dark academia" such as Donna Tartt's The Secret History usually explore morality within the setting of an academic institution. With Babel, Kuang expands the genre even further, building a dynasty of political and scholarly corruption that asks us to question everything we know about power, privilege, and knowledge.

The novel journeys to a speculative version of 1828 England, where a young Chinese orphan named Robin Swift—a name chosen at his mentor’s insistence—has been transplanted from Canton to study at Oxford’s prestigious Royal Institute of Translation, colloquially known as “Babel.” There, a select few will use their linguistic skills to harness an alchemy that keeps England not only up and running but in a position of global dominance. Here’s how the magic works: Translated words are etched onto silver bars to produce miraculous results, such as carriages that don't need horses to power them, previously untreatable diseases that can be instantly cured, and weapons that can destroy enemies on the other side of the globe.

But this magic has a dark side, fueled by greed and imperialism. As Western languages have begun to homogenize, Babel is forced to seek out and exploit native speakers from Eastern lands in order to keep the magic flowing. And yet, as Robin later discovers, this flow of resources is one-sided. England withholds this silver from other countries, hoarding it for itself and its rich citizens, with disastrous consequences for the nations denied access. Kuang cleverly creates a world in which words act as a finite resource, like oil or diamonds, that can be sold, stolen, depleted, or held captive.

Kuang—who herself is Chinese American and studied contemporary Chinese at Oxford— has seemingly written both a love letter to and a declaration of war on Oxford. The book teems with a devotion to higher learning—for one, the lavish use of educational footnotes to expound upon scenes and descriptions. But Kuang also isn’t afraid to challenge the traditional image of academia as being primarily rich, white, and elite. Robin’s class at Babel includes Ramy, originally from Calcutta and intent on stirring up change at Oxford, and Victoire, a Black girl from France who wants to explore her Haitian roots. Both have been brought to Babel by white mentors to exploit their knowledge of non-Western languages.

Despite their prowess, though, Robin, Ramy, and Victoire are still viewed as second-class citizens at Babel because of their race. The trio are often forced to hide or contort themselves in order to blend in with their white schoolmates, who have cartoonish names like Vincy Woolcombe and Milton St. Cloud. And at times they face blatant racism, as when, shortly after arriving at Oxford, Robin, and Ramy are chased by fellow students who refuse to believe that, as people of color, they belong on the campus.

Despite this, Robin enjoys his time at the institution until he gets wind of the Hermes Society, an underground group of current and ex-Babelers trying to dismantle the institution from the inside. Hermes opens Robin’s eyes to how England has built its empire on the backs of people deemed “barbarians.” As Robin investigates the etymology of the English language (an important part of Babel’s magic process), he begins to notice how many of its words have roots in other languages: coffee from the Arabic qahwah, taffeta from the Persian tafte, gingham from the Malay genggang. “English did not just borrow words from other languages; it was stuffed to the brim…and Robin found it incredible, how this country, whose citizens prided themselves so much on being better than the rest of the world, could not make it through an afternoon tea without borrowed goods.” These revelations torment Robin, who loves his comfortable life at Oxford but has come to despise the system that affords it. He is torn between staying quiet to survive and pushing back, thereby risking the life he’s built.

Babel is a heavy book, but that isn’t to say it isn't also fun. Kuang may be challenging the dark academia genre, but she clearly understands it well. There are whole pages dedicated to enthralling descriptions of Oxford's grounds and its massive, over-the-top libraries. Accounts of translation classes are so detailed, you feel as if you’re one of the course's eager students. Kuang also sprinkles in bite-size historical references that bring an immense amount of color to the book, and underscore that despite its fantasy elements, Babel is deeply rooted in history.

“History isn’t a pre-made tapestry that we’ve got to suffer, a closed world with no exit. We can form it. Make it.” Babel may be set in fantastical long-ago, but its reflections on race, colonialism, language, and power feel timely and relevant, pushing us to reflect on the past in order to create a more equitable future. If, as Babel suggests, words contain magic, then Kuang has written something spellbinding.

You Might Also Like