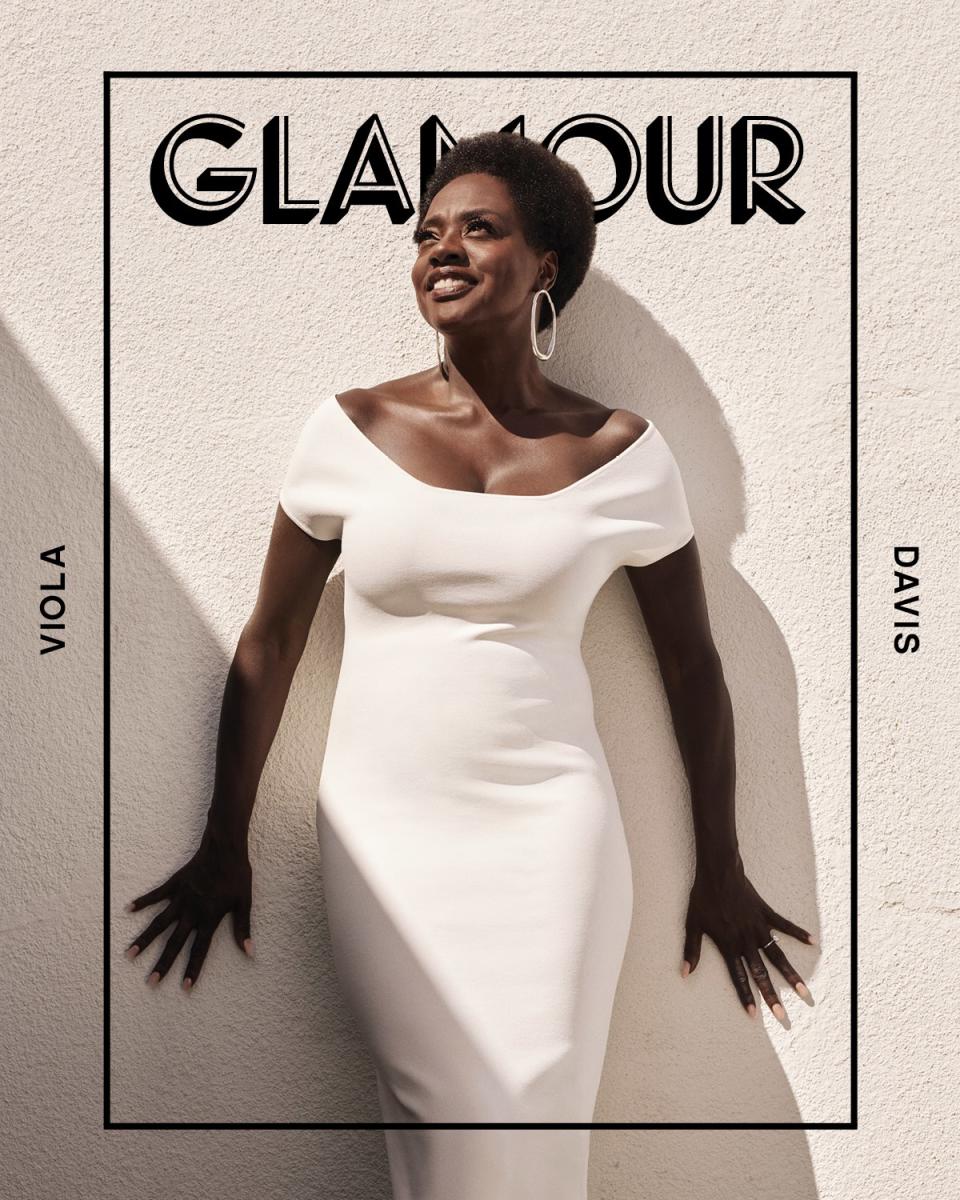

The Quiet Power of Viola Davis

In a cramped trailer on the set of the hit ABC show How to Get Away With Murder, I get to watch Viola Davis go into makeup. “I come in here busted up,” she says playfully, still holding what appears to be an already hour-old paper cup of coffee. “I just sit here, and they transform me.” She is smiling, perched in a vinyl makeup chair, her head loosely wrapped in a brown silk bonnet.

In the three-decades-long journey to this moment, Davis, 53, has played so many parts she says she can’t remember them all. If there is a woman with a struggle, Viola Davis has been asked—and has found a way—to inhabit her. Wives and maids. Doctors and artists. Grieving mothers and desperate drug addicts. In the female-led thriller Widows, out now, she’s the wife of a fallen heist man. Her performance, which is already garnering Oscar buzz, manages to cut prototypical crime-boss badassery with a roiling undercurrent of personal grief.

It is hard to say when Davis became an unofficial champion for overlooked women, but it’s a feeling she’s long understood. After graduating from Rhode Island College in 1988 with a degree in theater, she worked on stages from New York City to Edinburgh, Scotland, for a year before being accepted to Juilliard. (A monologue from The Color Purple served as her audition.) At the prestigious acting institution, Davis found herself struggling. She wasn’t prepared for the code-switching whiplash many black actresses experience going from playing barely literate slaves to Shakespearean queens. She also found that trying to speak in the stringent standards of prestige white theater didn’t connect with who she was internally. “I was angry a lot,” she says of those early days at Juilliard. “Nobody asked me to do [classical roles] as a black actress.” She ultimately found her voice through painful trial and error, “by really sucking at a lot of things,” she says, “giving a lot of bad performances.”

After college she spent several seasons honing her craft as a member of Trinity Repertory Company, in Providence, Rhode Island, taking whatever parts she could get. Her film debut wouldn’t come for another eight years, when she played an unnamed nurse alongside Timothy Hutton in 1996’s The Substance of Fire. I ask what kept her going during those long, lean years. “I was working,” she says. “I’ve heard less than one percent of our profession makes more than $50,000 a year. If you’re that actor who’s actually making a living—that’s what sustained me. Even if the work was bad, I was working.”

It would take another decade—and a devastatingly powerful turn opposite Meryl Streep in the 2008 film Doubt—for Davis to grab people’s attention once and for all. She had only one scene but blew a hole in the celluloid with her stunning portrayal of a mother tasked with an impossible decision: Keep her son at a Catholic school, despite possible evidence of molestation, or let him take his chances at a public school where he was bullied. “At first I didn’t understand her,” Davis says of her character’s decision to turn a blind eye to the abuse. An old acting teacher from Rhode Island College, she says, gave her the key. “ ‘I understand the choice,’ ” Davis recalls her teacher saying,“ ‘because she has no choice.’ That was the aha moment.”

“Winning,” Davis says of a childhood summer skit contest, “was our way of being valued and being seen.”

Carolina Herrera dress. Lizzie Fortunato earrings, $195.

Perhaps much of Davis’ life and career can be understood like this: really getting what it means to have no choice. She was part of the first black family in the working-class hamlet of Central Falls, Rhode Island. And they were poor. Not just normal poor, but something quite beyond. “Try telling your teacher that you can barely sit in your seat because your feet are two steps from being frostbitten,” she says. “No one can grasp that. Even people who have very little, at least they have very little. Try having close to nothing. You’re invisible.” This experience of being invisible, she believes, is what planted the seeds for not only her career as an actor but her work as a producer (JuVee Productions, the company she launched with her husband, Julius Tennon, focuses on projects dealing with race and justice) and a philanthropist. Davis is an ambassador for Hunger Is, a charitable program aimed at ending childhood hunger. Her upbringing, she says, “was ripe ground for me to have empathy for human beings.”

Along the way, there was some encouragement to help those seeds grow. At eight years old, she and her sisters performed a game show spoof at a summer skit contest in town. For costumes and props, the girls raided their parents’ closet and spent $2.50 at the Salvation Army. Davis recalls being the head writer, making last-minute changes to punch lines that still weren’t landing. The whole town was there, she tells me; kids who were her friends sat alongside the kids who called her and her family the N-word. The sketch was a smash, and Team Davis took home the top prize: a softball set and a mention in the local paper. From that moment on, she was hooked. “Winning,” she says, “was our way of being valued and being seen.”

At this part of our conversation, Davis dutifully unwraps the bonnet she’s wearing but not before making a handful of jokes about what it means to do this in front of a stranger. “It’s about to get serious,” she says, laughing. The character she’ll play in just a few minutes—the pugnacious and at times finespun law professor and defense attorney Annalise Keating—is infinitely put together. But Davis took the role on the condition that the character appear without a wig in some of her scenes at home. “I wanted to see a real woman on TV,” she explained during a panel discussion in the run-up to the 2015 Emmys. “I wanted to see who we are before we walk out the door in the morning and put on the mask of acceptability, ‘Please see me as pretty. Please love me.’ ”

At 53, with a Screen Actors Guild Award for The Help, an Emmy for Murder, two Tonys for King Hedley II and Fences, and an Oscar for reprising her role in the latter onscreen opposite Denzel Washington, Davis is far beyond the point of begging for love. The voices of everyone I spoke to, from costars to crew members, swelled with joy when I asked them to describe Davis. “I can’t even begin to tell you how much I love this woman,” says her Murder costar Aja Naomi King. “Because, first of all, to be a black actress, and to have watched the evolution of her career, it’s altered the way I have looked at this entire industry. Every time she wins, it feels like success for all of us. Because here’s the face of this beautiful, tall, striking, dark-skinned, natural hair- wearing black woman who is basically saying, ‘I dare you to tell me no.’” For Widows director Steve McQueen, Davis’ power lies in the depth of her vulnerability. “She’s shameless,” he says. “That’s why she resonates with so many people…. You recognize yourself. It’s like looking at yourself in a mirror.” And when I explain to her Widows costar Elizabeth Debicki that Davis is one of Glamour’s Women of the Year, the actress corrects me. “The woman of the year,” she says. “Singular. Only one.”

![“I was angry a lot,” Davis says of her time at Juilliard. “Nobody asked me to do [classical roles] as a black actress.”

Givenchy blouse. For her nude lip, try L’Oréal Paris Infallible Pro Matte Les Chocolats Scented Liquid Lipstick in Bittersweet ($10, lorealparisusa.com).](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/rn7a7cjz9AvPEmoHbiAlKA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTcyMA--/https://media.zenfs.com/en-US/homerun/glamour_497/8619dc3f20ee7a267c0ae0688b3f6575)

“I was angry a lot,” Davis says of her time at Juilliard. “Nobody asked me to do [classical roles] as a black actress.”

Givenchy blouse. For her nude lip, try L’Oréal Paris Infallible Pro Matte Les Chocolats Scented Liquid Lipstick in Bittersweet ($10, lorealparisusa.com).

Back in the trailer, Davis is revisiting her favorite roles. She loved James Brown’s Johnny-come-lately mother in the critically maligned biopic Get On Up (“I could recognize her as someone in my life,” Davis says). She loved Rose, in Fences—“she is woman personified.” But the one that makes her most wistful? The Earl of Kent, whom she played in a barely viewed staging of King Lear at the Public Theater in New York. “I wish more people could have seen me really transform into a man,” she says.

I want to take a picture with Davis, but I’m afraid to ask. So instead I tell her how much she means to me. How she is living a version of artistic humanity most of the black actors I studied with at Tisch School of the Arts never imagined would be allowed on a screen. She nods slowly—it’s hard for her to take compliments, but she’s working on it. “Because life is short and tomorrow is not promised,” she says. “And at some point you have to enjoy the fruits of your labor.”

Carvell Wallace is a writer in Oakland, California. His work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine.