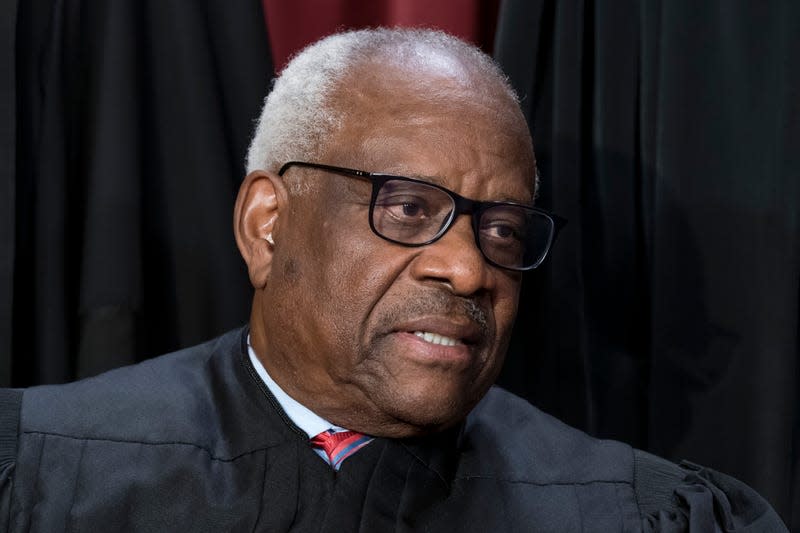

Why We Don't Buy That Clarence Thomas Loved Prince

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Clarence Thomas, yes that Clarence Thomas, said during oral arguments at the Supreme Court yesterday that he used to be a Prince fan in the ‘80s. I won’t even bother to get into the merits of the case Thomas and the other eight justices were hearing. You can read about that here. Or here. Or do your own Googles.

My curiosity, and likely yours, began and ended with that statement. Like Justice Elena Kagan, the first thing I wondered was, “Was?” as in, had been a fan of the legendary Prince Rogers Nelson, who to this day I imagine looking down on all of us in glorious disapproval from a violet throne in heaven? (I don’t know about you but I’m grateful for the promise of being frowned upon by an ethereal Prince; being unworthy of his genius is proof-of-life). But while we can all agree there’s no such thing as being an ex-Prince fan, I still need to know what ol’ Clarence was listening to in the ‘80s.

Read more

Remember this is the decade when Prince not only was at his most prolific but also in which Thomas’ alleged sexual harassment of Anita Hill happened. I Wanna Be Your Lover immediately comes to mind, though technically this hit debuted in ‘79. Was Thomas still into Prince by 1991, when his Supreme Court confirmation hearings got underway? Controversy would’ve been apropos, so long as Thomas was listening for the groove and not the lyrics. “Am I black or white/Am I straight or gay/Do I believe in God? Do I believe in me?” probably wouldn’t go over well in the early Christian conservative movement that supported his nomination.

Was pre-Justice Thomas just into the hits, or was he a deep cuts guy? Purple Rain and When Doves Cry or Alphabet Street and Thieves In The Temple? I need to know.

I also need to know if Thomas grasped the gravity of calling himself, among the most conservative members of the nation’s high court, a onetime fan of an artist who made righteous subversion his calling card. Prince made light work of blending themes of spirituality and sensuality. He thumbed his nose at convention. He prided himself on having an androgynous appearance and sung lyrics that made sexual fluidity visible in an era when open homophobia and transphobia generally went unchallenged.

Prince spoke to freedom, religious and sexual, while remaining a devout Jehovah’s Witness throughout his life. He centered women, their freedoms and agency, in his music and his bands. He portrayed a deep reverence for Black people and culture in the face of being one of the biggest crossover artists in history. Which is all to say that Prince, for the most part, was a walking antonym of Clarence Thomas, or at least the Thomas we’ve known since George H.W. Bush introduced him as an inexperienced but reliably conservative Supreme Court nominee.

Maybe that’s why Thomas was so specific about having been a fan in the ‘80s. These days, Prince just might not be his speed.