Quentin Blake: ‘Roald Dahl was a very different sort of person from me’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

I was born in Sidcup in 1932. It was perfect suburbia, with semi-detached pebble-dashed houses. There was no tradition at all of art at home. I mean, my father was a civil servant and my mother was a housewife. Almost everything I got, I got through school. By the time I went to secondary school, I think I could draw quite well.

While I was still at school, I used to submit drawings to Punch. I first had a drawing published in 1949. To have something printed was a real step in the direction of becoming an illustrator.

I didn’t go to an art school. In fact, I went to Cambridge and I read English there. I don’t regret that because learning to read books has a lot to do with what I’ve done ever since.

What I did do was go to life classes a couple of times a week. I would draw from the model and then you turn round and draw what you can remember, which alters it all. And then you go home and you do it again.

If you draw something that is in front of you, the amount of visual information you’re offered is too much to deal with. And I think if you go away, then you discover there’s some feeling that you can get down on paper; it isn’t only the technical information.

The observation that I did in life classes for two years seems to have lasted me ever since. I never look at something that I need to draw. If I have no reference, I just feel I know what happens, kind of thing. It may not be anatomically absolutely perfect, but it just comes out of the imagination or the old observations, unconscious observations of the past.

The curious thing about The BFG is it’s a book I’ve illustrated twice. I started it in one style and I did a dozen pictures, which is what the publishers asked me to do. And then Roald took a look at them and the message came: “He’s not happy.” And you knew if Roald wasn’t happy.

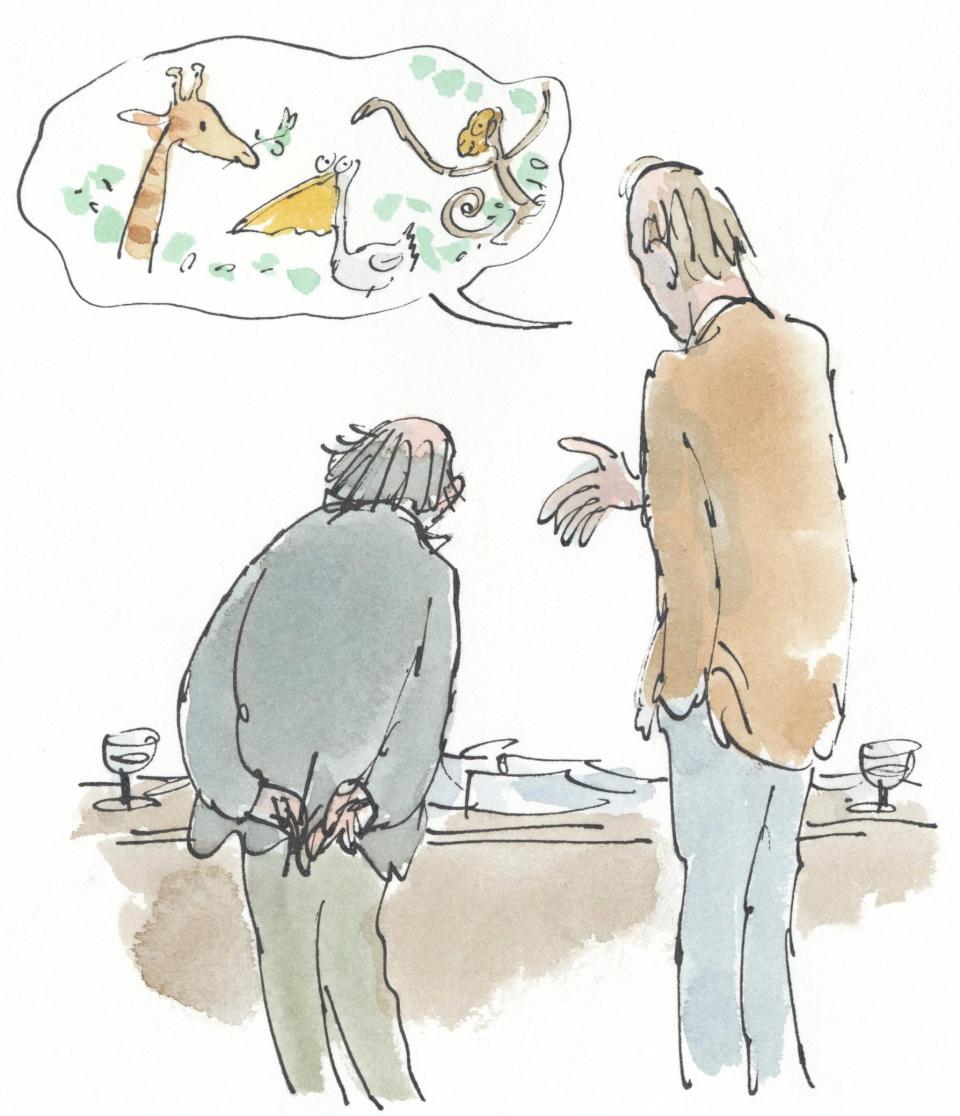

I don’t generally talk to authors a great deal, I relate to the text. But in this case we had an emergency situation. And so I went to his home in Great Missenden and we talked about it.

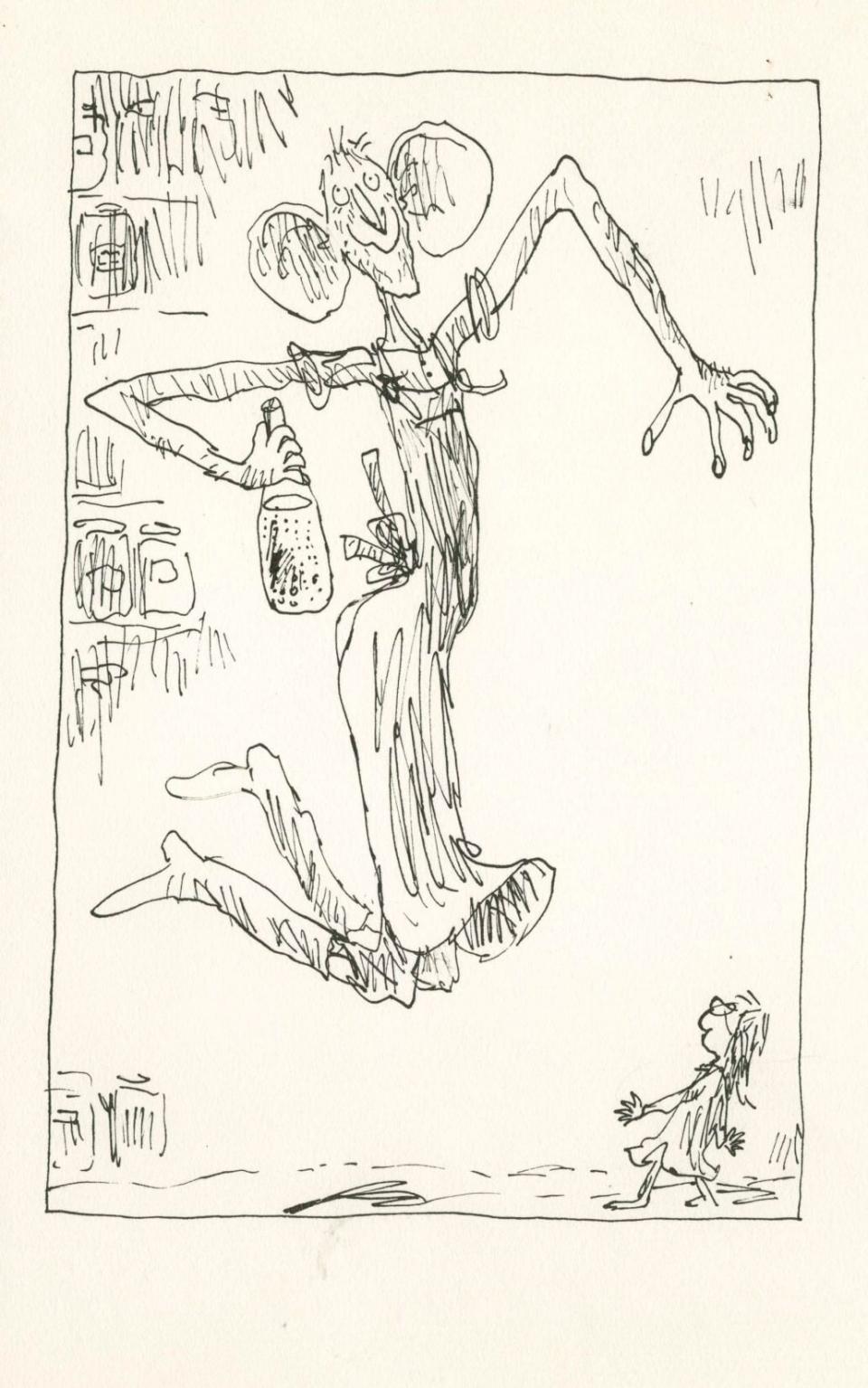

The first ones I’d done were like this (pictured below). This is an old friend – I’m interested to see it again. There is the BFG, a sort of slightly scratchy line drawing with the big ears, all right. It wasn’t that Roald wasn’t happy with the drawings, he liked them, all right, but there weren’t enough of them.

I’d had dinner with Roald, started talking to him about it, and what happened then was that we started again. We talked a lot about the costume. So when I first drew the BFG, he’s wearing an apron and boots, and that was a costume mentioned in the text. But, of course, he wears it in every picture of the book, and that’s where one started to find that it was inconvenient. It was difficult for him to run, and so on and so on.

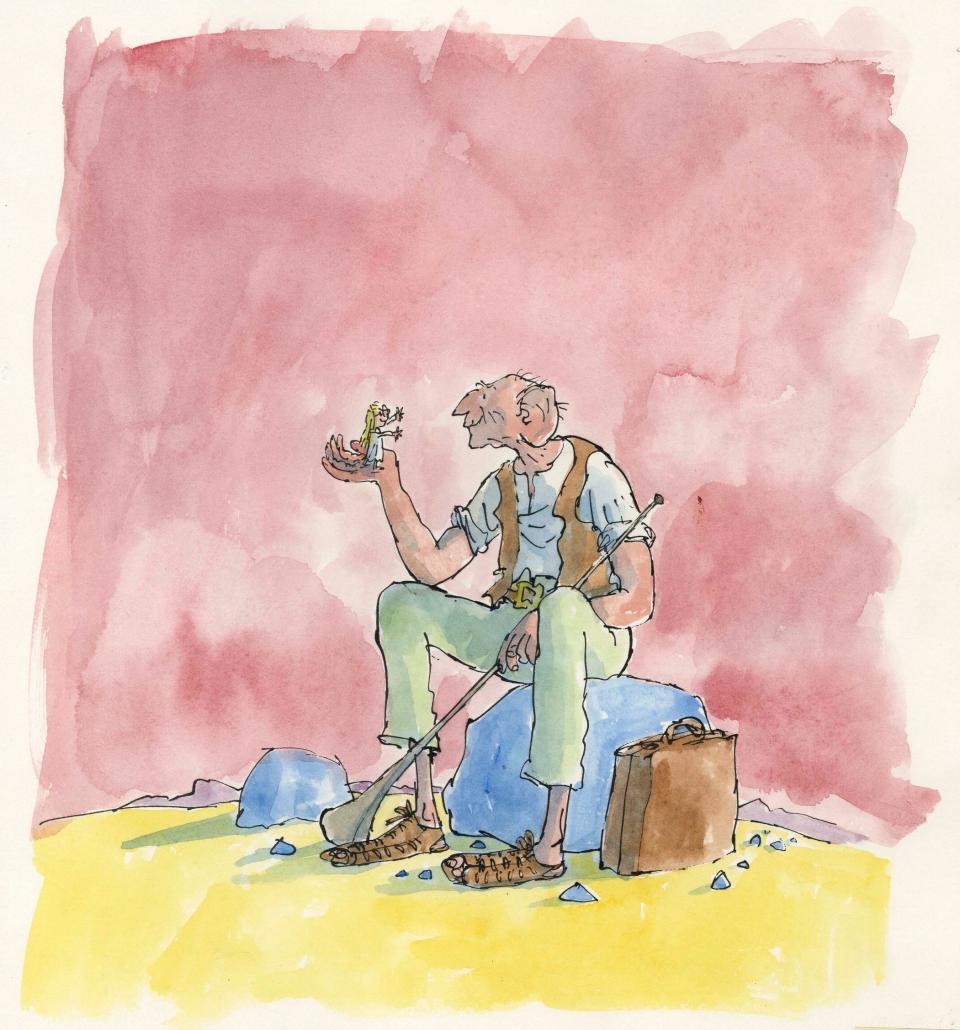

And there are some drawings that I did sat at the dinner table, and here the BFG’s got a sort of sack round his waist and a belt. And he’s got some kind of a vest. And he had a sort of hat, as well, a sort of cap. We eventually arrived at the costume that you see in the drawings now, except we couldn’t decide what he was going to wear on his feet. We didn’t want these big wellington boots.

So I went home and then a sort of shapeless brown-paper parcel arrived, tied with string. I opened it and inside was one of Roald’s own sandals. It’s Norwegian, I think. I’ve never seen them anywhere else. Those were Roald’s origins. And that’s what the BFG wears.

You get a sense of how close they are to each other, in a way. It’s one of his characters with which I’m sure he feels the most affinity. And it meant that the BFG as I drew him became more like a real person. I can remember he did say, when people talk about the BFG, “They see what Quent draws, you see,” which was very nice of him.

There were many good things about working with Roald. In certain situations, I think he could be difficult, but we got on very well. Roald was a very different sort of person from me, and in a way that was good, I think, you know, because if you’re a double act, you don’t want to be two versions of the same person. There is that contrast, and slight sort of tension.

Sometimes people say to me, “You seem to understand children very well,” or something like that, and I say, “Well, I don’t,” of course. I’ve never been married, I’ve never had any children. It’s not a question of knowing about children, but you be them.

What I feel about illustration is it’s like acting, so that you don’t look at people to see what they’re doing, you don’t have models to look at, you imagine you are that person. If it’s a dog, if it’s an old-age pensioner – I’m trying to be them, as well.

You know, perhaps when you’re acting and somebody says be angry or be happy or pretend you’ve got a limp, or something like that, you don’t really know how you do it, do you? You just want to do it. And so you try and produce that feeling or you make those expressions.

I can imagine things happening and I actually kind of mime them when I’m drawing them. And I’ve been told I make the faces of the people in the pictures. So it is like a kind of acting.

I like to think of books taking people away, not just to places, but to experience how other people feel and live and react. It’s about how to live more.

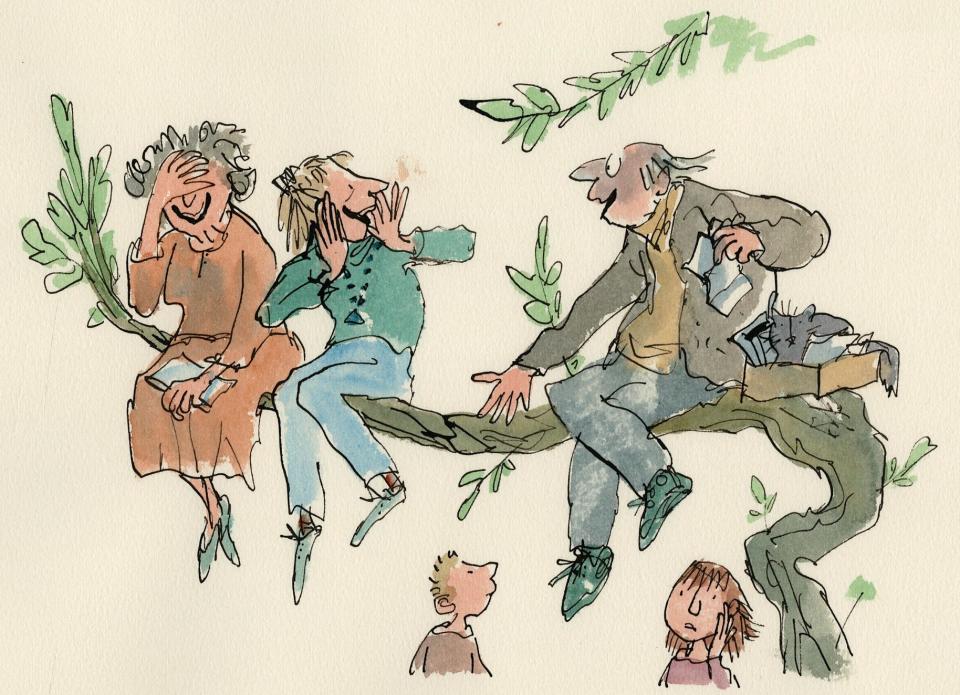

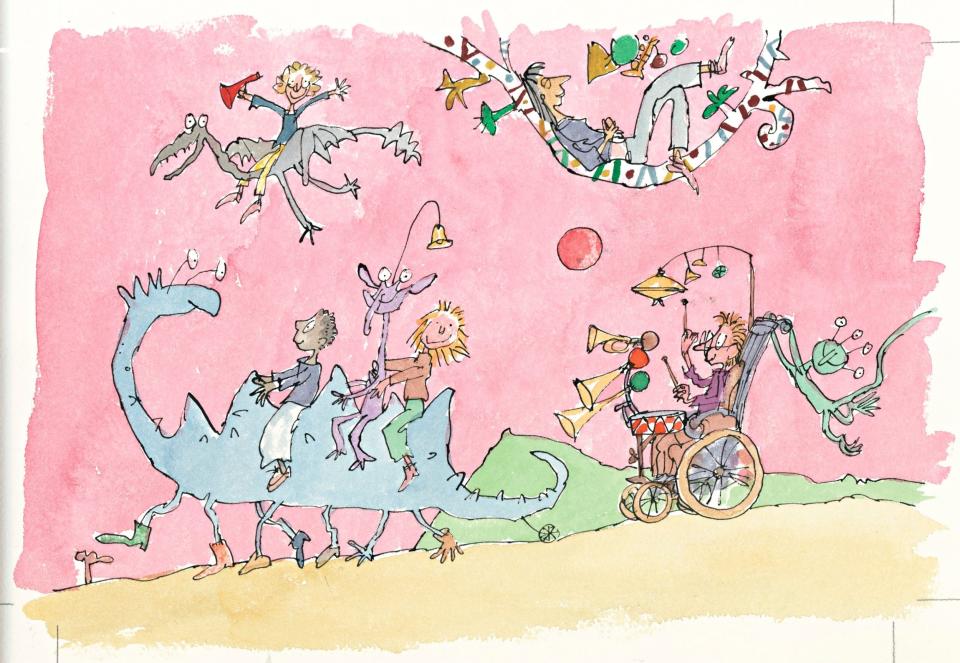

You might not know, but I’ve done a lot of drawings in hospitals. I was invited to do some pictures for a place for elderly people with mental health problems. That’s where I started. So I did a lot of pictures of people climbing about in trees mostly, actually, and it seemed to work for them.

It was very touching. There was an elderly lady, she said: “Oh, they encourage us to do all things we’re not supposed to do. It’s wonderful!”

Each of the hospital projects is sort of an illustration job, in that you have to address the situation and find out what the appropriate answer is. So, “Welcome to Planet Zog” goes in a waiting room for children.

The hospital is an alien environment and so Planet Zog is another strange environment, but it’s alright. There are aliens with several legs and that kind of thing in there, which correspond to the doctors and consultants, and they’re having their legs bandaged, as well. And so really it’s quite a simple message. Yes, it’s an alien environment, but the aliens can be quite nice.

I’m particularly interested in 19th-century illustrators. Those are my ancestors, I think; that’s how I regard them.

When I was 16, I bought a book of pictures by the French illustrator Honoré Daumier, all about Paris life. What is fascinating about them is that this is someone who draws with all the knowledge and quality of an old master – and you can buy it in a newspaper! They were tremendously influential on me. I mean, I wish I could do anything like it.

I bought this book for two guineas, and I remember my mother saying to me: “Are you sure you want to spend all that money on a book?” Well, I was absolutely right. I’ve had it ever since and I still look at it.

About 20 years ago, I did a drawing of myself, and it said: “From now on the rules of semi-retirement will come into play and there will be a lot of saying no.”

That was 1998, and I haven’t stopped since. I perhaps do less commissioned work now, but there’s no question of stopping drawing. No.

As told to Peter Sweasey for the Wingspan Productions documentary Quentin Blake: The Drawing of My Life, which is on BBC Two at 4.10pm on Christmas Day