Quasicrystals Were Once Impossible. Scientists Just Built the Biggest One Ever.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

Quasicrystal are structures that make up materials that are the bedrock of many modern technologies.

Scientists been aware of their existence since the early 80s. They have since found them both in nature and on nanometer or micrometer scales.

Now, scientists from the University of Paris-Saclay have created quasicrystals in a lab using millimeter-size metal spheres, revealing how these strange structures form.

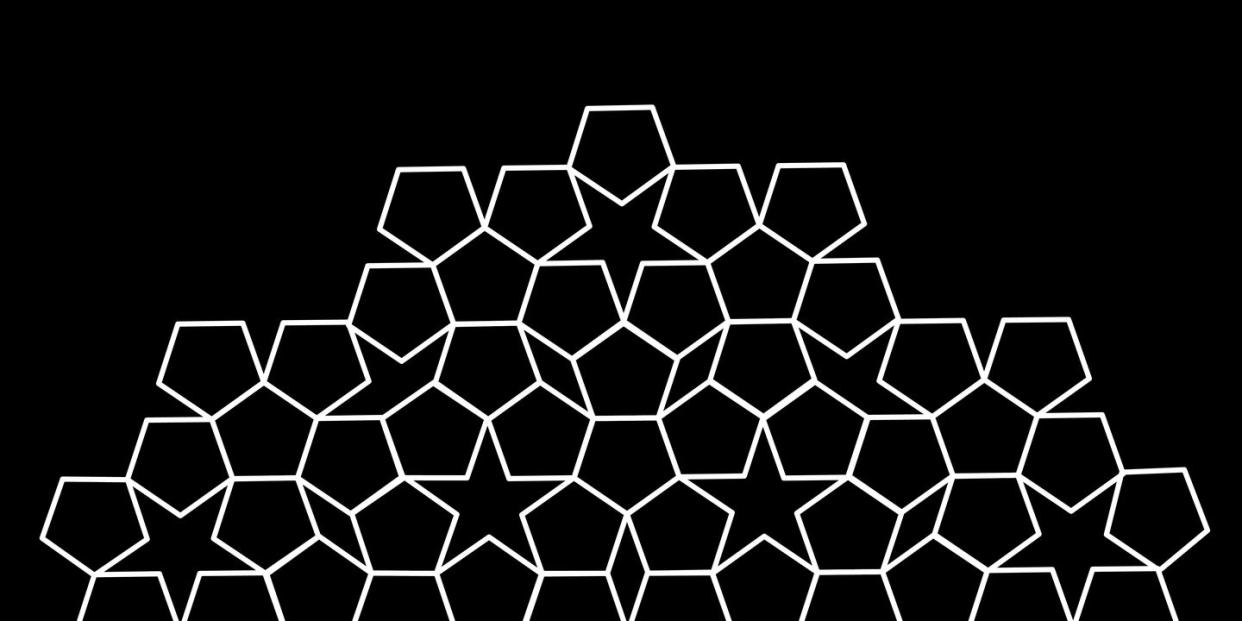

For decades, scientists considered quasicrystals an impossibility. Normal crystals are characterized by their arrangement of repeating atoms—whether in threefold or fourfold symmetries—but quasicrystals could contain five-fold symmetries that weren’t exactly repeating (hence quasi), but instead fill in the gaps with non-pentagonal shapes. In other words, they’re real oddities of the crystal world.

They were actually thought to be impossible until Israeli scientist Daniel Shechtman glimpsed them under a microscope on April 8, 1982. He even said at the time that “there can be no such creature.” The science community was so certain that this exotic class of materials couldn’t exist that Shechtman faced widespread criticism—he was even asked to leave the US National Institute of Standards and Technology, a laboratory in Gaithersburg, Maryland, where he made the discovery. Thankfully for Shechtman, vindication arrived in the form of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2011. Since then, scientists have even found some (but not many) quasicrystals in nature.

Fast forward 12 years later, and a team of physicists from France’s University of Paris-Saclay have successfully created the world’s largest quasi-crystalline structure in the lab.

“This was born as a bet with a colleague who said it would not work, but I said why not try it, it could be interesting,” University of Paris-Saclay physicist Giuseppe Foffi told New Scientist.

Foffi won the bet. The results are in a paper awaiting peer review on the arXiv preprint server.

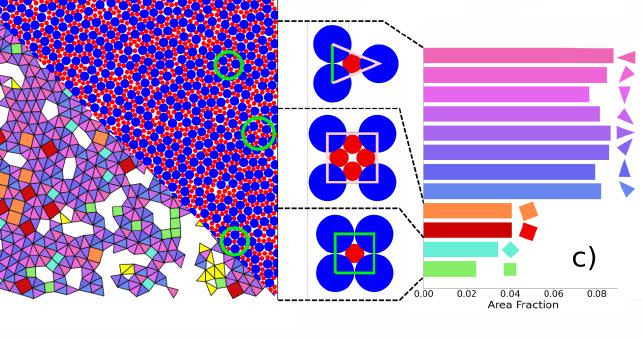

Scientists have known about nanometer or micrometer-sized quasicrystals, but Foffi wanted to see if he could create a quasicrystal nearly 1,000 times bigger. To do this, his team used 4,000 small spheres—either 2.4 or 1.2 millimeters in size—spread flat in a shallow box. After employing computer simulations to figure out the exact combination of spheres to use, the team vibrated the box of spheres at 120 hertz for 170 hours. Eventually, these spheres aligned in a quasi-crystalline shape, much like a tiled floor where the pattern never repeats.

Understanding how these structures form is incredibly important, as quasicrystals can have a wide range of different capabilities. According to NPR, quasicrystals can vary depending on their direction, for example, so that one structure is an excellent conductor while another is a poor one. They’re also found in everything from non-stick pans to surgical equipment.

Understanding the inner workings of these materials that were once thought to be impossible could unlock even more innovations.

You Might Also Like