At Qatar World Cup, Teams May Win But Brands Will Not

Over the past few weeks, rumors around fashion at the soccer World Cup in Qatar have been swirling.

There was a story about models due to work at a special fashion event there who were refusing to go because of the country’s record on LGBTQ rights, and gossip that some of the biggest names in the fashion world were thinking about pulling out of the same mega-runway event for similar reasons. There were also rumors that traditional sportsman-like behaviors, such as hugging after scoring a goal, would need to be altered in the socially conservative country. Those surfaced after Khalid Salman, World Cup ambassador and former international footballer for Qatar, described homosexuality as “damage in the mind” during a TV interview in early November.

More from WWD

But those rumors are said to be false: British media have reported on conversations between officials from FIFA, the event’s organizing body, and Qatari authorities in which the Qataris said that, during the World Cup, security staff would take a more lenient attitude toward things that are usually unacceptable in the country, including public displays of affection, wearing or carrying a rainbow flag, unmarried couples staying in the same room, as well as standing on a table or chair and singing a football fan song.

Usually in Qatar, a traditionalist Muslim monarchy, homosexuality is criminalized and consensual sex outside of marriage is illegal, as is campaigning for gay rights.

The chatter about the fashion show isn’t true either, a spokesperson from CR Runway, the Carine Roitfeld-helmed organization that is coordinating the aforementioned fashion show, told WWD. The event, called Qatar Fashion United by CR Runway, is going ahead as planned and will feature some of the biggest names in the fashion world as well as emerging designers from five continents, the company said. Dior, Gucci, Louis Vuitton and Prada are among the planned participants.

“No designer or brand has pulled out of the fashion show,” the CR Runway spokesperson added. “We can confirm all 150 brands and designers will participate and there have been no changes.”

But while the rumors are just that — rumors — there is growing unease about being too closely associated with the Qatar-hosted World Cup.

It is understood that several fashion brands are fulfilling contractual obligations but trying to keep a lower profile around the event and that one business is even postponing a store opening in Qatar because of the negative atmosphere.

The reasons for the discomfort are a number of concerns about Qatar as the host country.

The contest to become a host country for the World Cup, which happens every four years, is intense. As one of the most watched sports contests in the world, with an estimated 5 billion viewers, it is seen as an unparalleled opportunity to showcase the host country. Qatar was awarded the event in 2010 at the same time that Russia was nominated host of the 2018 World Cup.

The decision was plagued by controversy, including suspicions that the Qatar delegation had used money and favors to “buy” votes of FIFA members, who made them the hosts. Since 2015, Swiss and U.S. officials have investigated corruption within FIFA. Russia and Qatar were both cleared of any wrongdoing in 2017.

On one hand, the decision to award Qatar the contest was seen as illogical. The country would have to build new stadiums and the timing of the competition, which usually takes place during the Northern Hemisphere’s summer, would have to be changed. It would be too hot to play soccer in Qatar at the time the contest was usually held.

On the other hand, FIFA justified the decision by hailing the fact that, for the first time, the World Cup would take place in the Middle East.

Nonetheless, the Qatar World Cup has been dogged by disputes and accusations of “sports washing” — using sports to polish a tarnished reputation — ever since. Human rights organizations, including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, claim that at least 6,500 workers, many of whom migrated from Asia to work on the stadiums, died in Qatar due to inhumane and unsafe working conditions. Qatar spent more than $220 billion on construction for the World Cup, and has refuted allegations that it mistreated workers.

Rights organizations have also highlighted the dire situation for women’s rights in Qatar, where women have to obtain permission from their male guardians for many major life decisions, including who they can marry and where they can travel. There are also limits on freedom of expression, with democracy monitor Freedom House ranking Qatar as “not free.” Other organizations like Greenpeace have spoken out about the environmental impact of the huge football stadiums, some of which require air conditioning, which is not always required for stadiums in cooler regions.

As a result, various national teams — including 10 European squads, the Australian and the U.S. teams, along with several popular clubs, like Borussia Dortmund in Germany — have spoken out about their unease at playing in Qatar. “Human rights are universal,” the European teams said in a joint statement issued in early November.

Some of the national teams playing at Qatar will now take part in the One Love initiative, a Netherlands pro-diversity campaign, and have their captains wear rainbow-colored armbands in support of the LGBTQ community.

In France, the authorities in several major cities, including Paris, Strasbourg and Lille, France, have said they won’t be setting up outdoor viewing areas to watch the games in protest. An official in Paris explained the city’s decision was because of environmental and human rights concerns, and Strasbourg’s mayor spoke about the exploitation of migrant workers as being her city’s reason.

At the same time, celebrities like former footballer David Beckham, who reportedly signed a 10 million pound deal to appear in the marketing campaign for the event, and model Naomi Campbell, who is launching an initiative for emerging designers together with a Qatari foundation, have come in for hefty criticism from the LGBTQ community and others.

Given all this, it is perhaps no surprise that the event has become something of a marketing quagmire.

And in the fashion world, only a handful of small brands and industry insiders have been outspoken on the subject.

“It’s worth noting that people are putting on fashion events in a country that completely negates the values many in the industry are supposed to have,” Markus Ebner, the founder of German indie fashion magazine Achtung, told WWD.

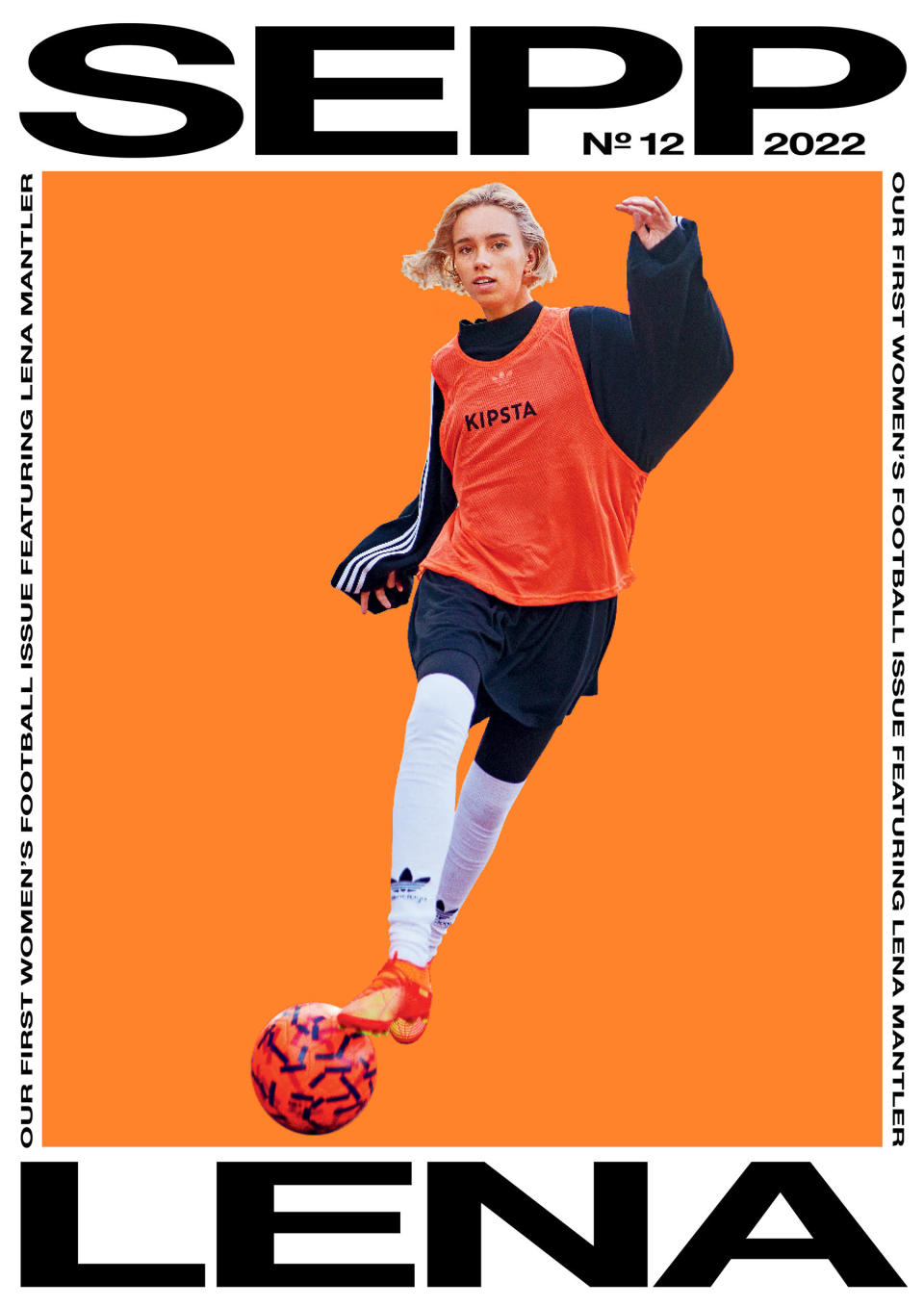

Achtung publishes a biennial football fashion magazine, called Sepp, usually to coincide with either the European football championships or the World Cup, both of which happen every four years. However this year, Ebner said, Sepp is bypassing the World Cup and the 2022 issue focuses on the women’s European football championship, which was held over the summer.

The Qatar World Cup is just “bad news,” Ebner said of why Sepp is focused on the female game in the magazine’s latest issue. “The things that Khalid Salman was saying [about being gay], the fashion and magazine world is completely against that,” Ebner told WWD.

As an observer of fashion and football over the past decade, the Sepp publisher said there’s a comparatively muted response to this year’s World Cup. “I feel like everyone got the memo and is trying to stay out of it,” he said.

One larger clothing company that has been more open with its concerns is Danish sportswear brand Hummel. The company’s uniform for the Danish team will be almost-plain red or white with an extra black shirt that represents mourning for the laborers who died while building the stadiums.

“We don’t wish to be visible during a tournament that has cost thousands of people their lives,” Hummel said in a statement on its Instagram page. “We support the Danish national team all the way, but that isn’t the same as supporting Qatar as a host nation.”

Still, there hasn’t been much criticism of Qatar from the fashion sector.

“It comes down to a very simple fact that these entities, whether in the fashion sector or elsewhere, are businesses first, and brands second,” said Harry Lang, a British marketing expert who regularly writes about sports marketing and the author of “Brands, Bandwagons & Bullshit,” a book about marketing.

“As a brand, they might have some good intentions about human rights or best practices, and they might want to make noise about it. But their first priority is business and the commercial obligation to make money,” he said.

This is especially true of the luxury sector, Lang theorizes, which continue to do well and which appeals to a lot of high-net-worth individuals living in this part of the Middle East.

The Qatari royal family, through various investment funds, is involved in the fashion and luxury sector and owns the brands Valentino, Balmain and Pal Zileri, as well as the British department store Harrods and French chain Printemps. The latter opened its first store outside France, in Doha, in early November.

The Qataris have also regularly courted some of the biggest names in the business by funding glamorous events like the recent Fashion Trust Arabia prize, which promotes emerging designers in the region, as well as such things as a major exhibition for Italian brand Off White in a Doha museum.

As former Puma boss — and incoming Adidas chief executive officer — Bjorn Gulden has pointed out, in clothing, every sponsoring opportunity brings its own challenges and all factors need to be weighed.

“Unless a brand has actually made its name from having a social conscience and having a good corporate social responsibility policy — brands like Patagonia, for example — then I don’t necessarily see them changing hugely [because of the World Cup],” Lang continued. “That is, until something starts either negatively or positively affecting their brand’s worth, and thus their sales capability.”

Market insights company Global Data has noted that World Cup sponsorship revenues — the money FIFA makes by partnering with brands at the event — fell 16 percent since the 2014 World Cup in Brazil, dropping from $1.35 billion to $1.1 billion this year. In a statement, the company’s analysts suggested that concerns over the Qatar tournament might have played a part in the decrease. It also noted that as Western sponsors like Sony and Johnson & Johnson have dropped out, their places have been taken by Chinese and Middle Eastern companies, like Wanda Group and Qatar Airways.

And it is the larger Western brands and event sponsors with long-term or contractual obligations to the event or to FIFA that continue to feel the most pressure.

For example, German sportswear giant Adidas makes outfits for seven national teams, including those of Germany, Belgium, Argentina and Mexico, and is a long-term sponsor of the World Cup, with its annual brand partnership estimated to be worth $50 billion, according to Global Data. After human rights organizations sent an open letter to FIFA last July, demanding compensation for migrant laborers and their families, who mostly come from Nepal, India, the Philippines and Africa, Adidas was one of only four of the event’s major sponsors to issue a statement of support. The others were McDonald’s, Budweiser and Coca-Cola.

This behavior aligns with one of the two routes most brands seem to be taking through the increasingly pressured, marketing morass around the World Cup.

The first involves keeping a lower profile. Sector observers have already noted that much of the advertising around the World Cup has not emphasized the Qatar connection in a big way, if at all.

Larger corporations have also done things like cut back on hospitality offers around the event. Major sponsors of the Dutch national team, including the multinational ING bank and the Albert Heijn supermarket chain, are not using their ticket options and will not travel to Qatar. Belgian team sponsors, including chocolate brand Côte d’Or and courier service GLS, have said they won’t go either.

The other route involves emphasizing the good that a company can do by turning up in Qatar.

In Adidas’ statement of support, the company said it would take up human rights issues with FIFA. And, as CR Runway’s spokesperson told WWD, the fashion mega-show they are planning is meant to “showcase the next generation of remarkable design talent from every corner of the globe…contribute to their countries’ cultural and social development” and “open doors and create equal opportunities.”

Qatar Fashion United by CR Runway is associated with a Qatar-based education foundation, Education Above All, the spokesperson stressed, and all proceeds from the show will go to the organization.

That’s the right way to play it, said Carrie Parker, chief marketing officer at Brandwatch, a U.K.-headquartered business providing companies with market intelligence and social media insights.

“Participating brands need to walk a tightrope and make it very clear what they are supporting,” she told WWD. “That is, the athletes, the competing countries, the sport. And then they should ensure clarity on what they do not endorse associated with this event.”

The question now is whether all of the controversy simply fades away once the first whistle blows — and sports marketing experts are divided.

It’s not likely, said Paloma Castro Martinez de Tejada, a partner at Paris-based brand strategist Darwin Associates. Because it’s part of a broader social change among consumers where they are demanding more social responsibility from their favorite brands, she said.

The World Cup in Qatar “is the outcome of something that happened over 10 years ago,” Castro Martinez de Tejada told WWD. “Possibly, back then, it was even done to give a small country a chance to shine. But 10 years later, and we are looking at a very different landscape.”

It’s important to be pragmatic, Castro Martinez de Tejada, a former global director for LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton corporate affairs, conceded. But in an age where consumers are demanding more accountability, brands, she said, “cannot afford to be ambivalent.”