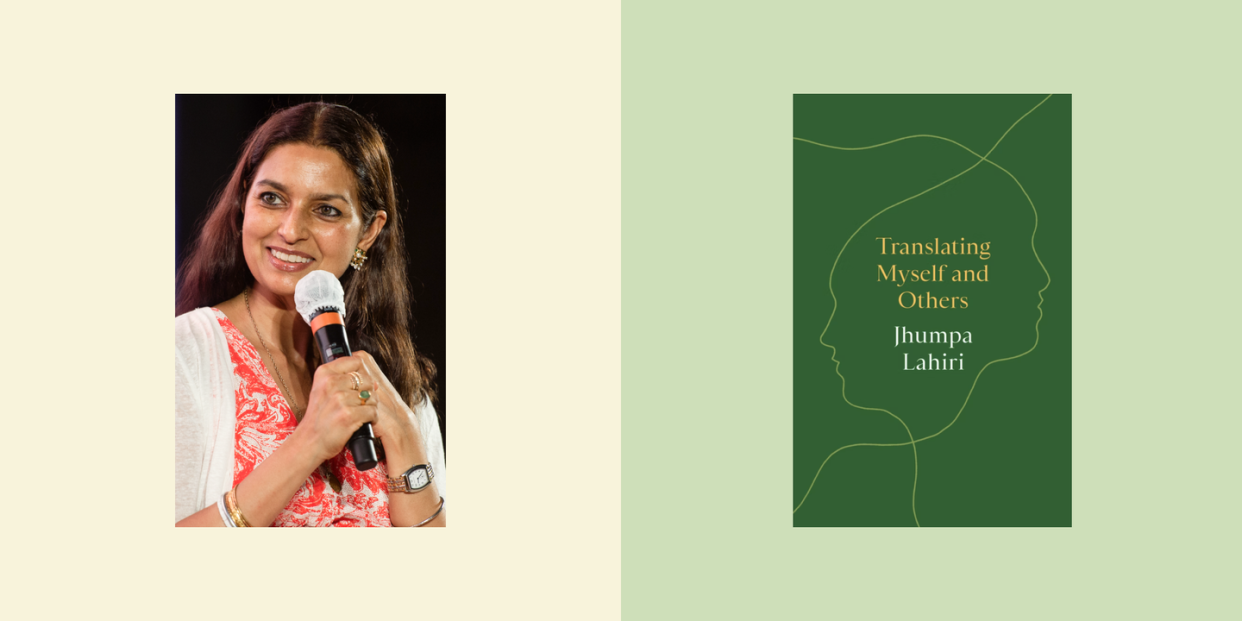

Pulitzer Prize Winner Jhumpa Lahiri’s Afterword from Her New Book, “Translating Myself and Others”

The winner of the Pulitzer Prize and other accolades and an abiding figure in literary culture, Jhumpa Lahiri wears various hats: novelist, story writer, critic, translator. This last role has fired her imagination over the past decade, after a 2011 move to Rome, where she immersed herself in the lavish music of the Italian language. Now a professor at Princeton, she’s turned to arguably her most ambitious project: a years-long English rendering of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the magisterial Latin poem from the first century CE. She’s collaborating with Yelena Baraz, a scholar in Princeton’s classics department. In an exclusive, Oprah Daily excerpts “Translating Translation,” the afterword from Translating Myself and Others, out next month from Princeton University Press.

Lahiri’s early days with Ovid overlapped with a wave of Covid shutdowns and her mother’s final illness. With her internal compass off-kilter, Lahiri and Baraz pored over Ovid’s epic in the university’s classics library, a sanctuary where the requisite masks and social distancing no longer seemed nuisances. “I felt protected not only by the beautiful, spartan, and ghostly room, but by the beauty of the poem itself,” she notes. Amid grief and a world in flux, she found her way back to what the Greeks and Romans knew: the interconnectedness of the cosmos, its wheels and gears grinding in cycles of renewal. Our bodies are stardust—no energy is lost, no molecules vanish. They transform. —Hamilton Cain, contributing editor at Oprah Daily

Translating Transformation

Ovid

In January 2021, I traveled from Princeton to Rhode Island to visit my mother. I had not seen her other than on Zoom since the previous August. I was concerned for her health; she complained of less and less energy and sounded out of breath on the phone. When I entered the house, she wasn’t in the kitchen excitedly putting finishing touches on the food she planned to serve as soon as my family and I arrived. Instead, she was sitting quietly in her armchair and did not stand up to greet us when we stood before her. In the five days I spent with her, she barely entered the kitchen. When we sat down to play Scrabble, her hands kept shifting the tiles previously arranged on the board. Her voice, once supple and expressive, had drained to a murmur.

The following week, in Princeton, I took a walk with Yelena Baraz, my colleague in the Classics Department. I told Yelena that my mother was in considerable decline; that in certain fundamental ways, she no longer resembled the woman who had raised me. We spoke about the difficulty of watching loved ones age and alter. As we were about to part ways, Yelena changed the topic, and proposed translating Ovid’s Metamorphoses, together. It would be a new translation published by Modern Library, the first English version of the poem translated by two women.

Yelena knew of my reverence for the text. The previous semester, we’d co-taught sections of the Metamorphoses, in English, in a Humanities Capstone seminar we’d conceived together called “Ancient Plots, Modern Twists.” It had been a lifeline for both of us during the long Pandemic Fall of 2020. She knew that I’d looked to Ovid—to the myth of Apollo and Daphne—to describe the process of becoming a writer in Italian in In Other Words. Ever since I’d begun teaching at Princeton, the Metamorphoses had been an increasingly pertinent point of reference for my translation workshops, and my reflections based on those workshops generated the essay on Echo and Narcissus that appears earlier in this volume, as well as additional essays and lectures building on the theme of translation. For years I had been telling students that the Metamorphoses, governed by ambiguity, instability, and acts of becoming, was a trenchant metaphor for the process of converting literary texts from one language to another. In keeping with the plot of my creative journey, translating Ovid’s masterpiece was the next logical twist.

That said, I had not read Latin with facility since my undergraduate years. It was one thing to pull out my Latin dictionary and look closely, now and then, at a few lines of the Metamorphoses in its original form. Translating all 15 books—11,995 lines, to be precise—would be another. Mount Everest came immediately to mind. And at the same time, a shiver of destiny. As daunting as the task felt, I knew that Yelena would be accompanying me, and on that cold January day, my heart heavy with the knowledge that my mother was transforming, I said yes.

We began by preparing a sample section for the editor, choosing the myth of Io in book 1—a double metamorphosis in which a girl is turned into a cow and back again. Yelena kindly arranged for me to use the Classics Graduate Study Room at Firestone Library. There I sat, alone, at a beautiful large wooden table, behind a partly frosted glass wall, before three Roman epitaphs from the second century BCE. In that room, removed from everyday reality, every edition of Ovid, every commentary, and every dictionary I might possibly need was at arm’s reach. Something about the silence there, and the three Roman epitaphs, and the red Eames armchair where I would take breaks, grounded me. As in my study in Rome, there was a single window facing east. Only Ovid kept me company in that room, and I was able to keep most other thoughts at bay. I was scarcely aware of the hours that passed, and was always sad to pack up and go.

Though Yelena was providing literal translations of the text, I was determined to reengage directly with the Latin on my own terms. I therefore transformed from a 53-year-old professor into my undergraduate self: Once again I grew used to looking up countless words in the big two-volume Oxford Latin dictionary, studying their dense, ample definitions, and stopping to ponder and unpack the syntax line by line. A small notebook of words—an arbitrary handwritten dictionary of terms that required further reflection, another practice of my undergraduate years—began to fill up.

As is the case in Ovid’s poem, the transformed individual is never free of the former consciousness. And so I was constantly reminded of the degree to which my Latin had faded. Like Ovid’s poem, which insists on hybridity, Latin was both old and new, in turns familiar and confounding. I’d forgotten entirely about deponent verbs and future participles. But I soon realized that something had changed, and that I was reading Latin differently compared to my college years. Now, more often than consulting an English-Latin dictionary, I turned to an Italian-Latin one. In my notebook, the definitions I jotted down were all in Italian, a language which is of course a direct metamorphosis of Latin itself. For, though the objective was to translate Ovid into English, I now had a new linguistic point of entry that positioned me closer to Latin than ever before. The itinerary of my translation was no longer point-to-point but triangulated, given that I was now reading him, instinctively, with an Italian brain. The process felt richer, more intimate, more revelatory, and even more satisfying.

Though I read slowly and haltingly, I also fell headlong into the poem, as if swept up myself in the current of the River Peneus that boldly opens the Io episode: “churning with frothy waves and tossing up clouds / as it cascades down, releasing a faint mist / that showers the treetops with spray / and assails distant regions with its thunder.”1 I remembered the excitement, decades ago, of encountering Ovid’s figurative language, his textual playfulness, his descriptions of nature. I marveled at all the words that defined the sea and the sky. I was struck by descriptions of aching states of separation between parents and children.

Once a week, usually on Friday afternoons, Yelena and I would meet and discuss the lines we’d prepared, masked at opposite ends of a table in the Classics Library in East Pyne Hall. This, too, felt both old and new, and it also felt mildly transgressive; with only a handful of professors on campus, all of us rigorously abiding to testing protocols and social distancing rules, it was the only consistent in-person contact I’d had with a colleague in a year. We questioned and discussed and corrected and adjusted the translation-in-progress, flagging troubling bits to return to. We talked about how to resolve Ovid’s penchant for using multiple names or epithets to identify characters, how to translate acts of sexual violence. We talked about how to reproduce the alliteration that runs rampant in the poem, how to honor golden lines. We looked at ancient atlases to trace the coordinates of Ovid’s inventive geography.

By early March, we had made it to the myth of Apollo and Daphne, which resonated with me in particular. As I’ve said earlier, I had drawn on that myth, in which a nymph is turned into a laurel tree to maintain her freedom, to describe the process of shifting from writing in English to Italian. One day, sitting in the armchair and peering through the grille of the heating unit, a small yellow label caught my eye. Examining it closely, I realized it covered an on-off lever, and was stunned to discover that there was a word written on it: Apollo. It was the name of the company that fabricated the heater. The healing god.

I felt protected not only by the beautiful, spartan, and ghostly room, but by the beauty of the poem itself. The Latin contained me like Peneus’s penetralia, his innermost chamber, even though, as a translator, I had to swim away from it. It occurred to me that the letters in Ovid, rearranged, spell void.

I started visiting the Classics Graduate Study Room nearly every day of the week, and often on weekends. The more I intuited my mother’s end, the more galvanizing it felt to be at the start of a long translation, a project that would take several years and the conclusion of which was far beyond my sight. And the more I feared my mother was slipping away, the more I felt comforted by those three gray inscribed tablets looking over my shoulder, honoring four souls—two male, two female—dedicated to the spirits of the dead, dis manibus: Primus Apollinaris (who lived 22 years, eight months), Venustus (who lived eight years, four months, 15 days), Aurelia Iusta, and Artellia Myrtale. All three tablets were dedicated by Roman family members: by a mother, a sister, a husband, an unspecified relative. It struck me that Aurelia Iusta’s epitaph, at the center, was made by herself while still alive: Se biva fecit2 (“while still alive . . . [she] made this”), to commemorate herself, her husband, and her son.

One day as I was translating in that room, my mother called me. It was a FaceTime call; for several weeks, she could only communicate if she could see my face, perhaps because she was aided by my image and expressions. As we were speaking that day, my father turned on the microwave in their kitchen, and because a space heater was also running, all the lights temporarily went out in their apartment. As my father went down to the basement, guided by a flashlight, to flip the switches on the fuse box, I looked at my mother’s face on my cellphone screen, floating in a pool of darkness. It was one of many premonitions I was to feel in the final weeks of my mother’s life, including a perfect hole that mysteriously formed in the middle of a bar of white hand soap in my bathroom, and a violent wind that flattened the peonies and shook the petals off the rosebushes in our garden. By then I was so ensconced inside the Metamorphoses that everything seemed Ovidian. The wind that coursed through Princeton evoked “horrifer [chilling] Boreas”; the unsettling dark hole in the white bar of soap summoned Callisto and Arcas snatched up “in a wind-born void,” and paradoxically suggested even a microscopic version of the primordial chaos described in the Creation: “a rough, unprocessed mass, nothing but an inert clump heaped together in one spot.”3

By the middle of March, more and more people I knew were getting vaccinated against the coronavirus, and the snow that had covered Princeton for nearly a month was finally beginning to melt. The emerging crocuses did not console me, nor did that collective, growing sense of hope. Only Ovid did. Only a poem in which humans, or human-like beings, were transforming page after page into stone, stars, animals, plants, water, and other elements, made sense. Only those myths and legends that Ovid translated and transformed in his own right, from previous incarnations, contained meaning. Only that liminal zone where identity is reshaped and redefined. Translating the Metamorphoses was not only resurrecting my Latin, but reminding me that there is no plot without change.

In late March, I traveled to Rhode Island to visit my mother in the hospital—the same hospital in which she gave birth to my sister in 1974 and became a mother for the second time. She had been admitted a few days earlier, when her doctor, after observing her at home during a telehealth appointment, wanted to rule out the possibility of a stroke. She had not had a stroke. Instead, tests revealed that there was too much carbon dioxide in her blood, and we were told that her life was ending. I both accepted and did not accept this fact. For though I knew that her time was limited, I kept thinking to myself, she’s not dying as much as becoming something else. In the face of death, the Metamorphoses had completely altered my perspective. Every transformation in the poem now assumed a new shade of meaning. Though certain beings do die in Ovid, the vast majority cease to be one thing but become something else. I was convinced that it was the inevitable passage from life to death that Ovid was recounting and representing again and again in order to enable us, his readers, to bear the inevitable loss of others.

nec quidquam nisi pondus iners congestaque eodem” (1.7–8).

We were told, in my mother’s final days, to read a booklet that would help us to interpret the signs of her bodily transformation. We studied the color of her nails, the temperature of her skin, her insatiable thirst, her voice, which had dwindled to a whisper. Each alteration felt astonishing in its own way. I kept thinking of Ovid, and how charged each moment of transition is; charged due to its very precision. The narrative slows down and verb tense often changes from past to present as the metamorphosis, bristling with specificity, commands the reader’s attention. As my mother’s penmanship became inscrutable, as her already compromised speech dwindled from brief sentences to words to near silence, I thought of the many characters in the poem—more often than not women—who are deprived of language. I wanted to pray for her but knew no prayers. The first line of the Metamorphoses, which I’d write on the blackboard the first day of my translation workshops, which I’ve cited earlier in writing about Domenico Starnone, became one. I memorized it and kept saying it in my head, hoping it would accompany her: “In nova fert animus mutatas dicere formas / corpora.”4

On the day we brought my mother home from the hospital, four days before she died, I followed her in the ambulance by car, stopping off to buy two potted plants—a hydrangea and a daffodil—to keep her company.5 My mother loved plants, and they always thrived under her care. After arranging them on her dressing table, I asked her if she liked them. She immediately replied, pointing, that she would continue to dwell inside them. She said this with a calm conviction. It was as if she had intuited the force of Ovid’s poetry that was flowing like an antidote through my veins. Her words to me that day turned her, too, into a version of Daphne, reinforcing our bond, and they enable me to translate her unalterable absence into everything that is green and rooted under the sun.

ROME, 2021

You Might Also Like