The Progressive Prophet Naomi Klein, Hope, Terror and Climate Change

This past June, Naomi Klein makes her way through the crowd outside the Bloor Street United Church in Toronto. There are young people chalking slogans on the sidewalk, old people leaning on canes, and a contingent wearing neon-pink “Justice for Foodora Couriers” T-shirts. All are there for an event titled A Green New Deal for All, at which the last speaker will be Klein, an author, intellectual, and environmental activist who is one of the leading progressive voices of our time. She looks up at the building, a rugged 129-year-old stone structure. “This is a very run-down church,” she says matter-of-factly. “We could have all kinds of technical problems.”

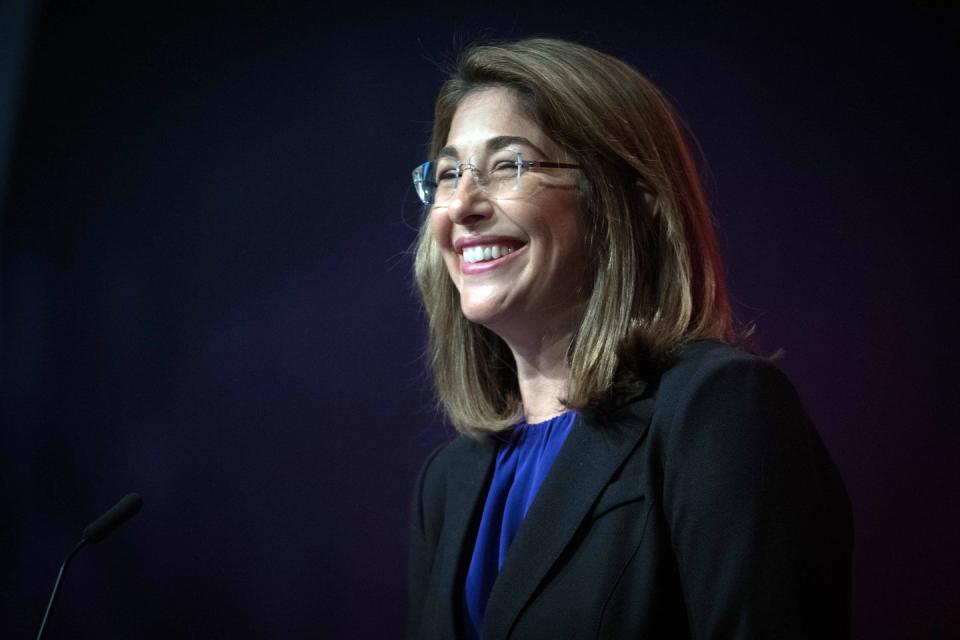

Klein is wearing, as she often does, dark, chic but inconspicuous clothing; rimless glasses; and a statement necklace, her hair in a version of the neat blowout she’s maintained for the last 20 years. “Sometimes I get strong urges to pierce everything in sight and stop looking so acceptable,” Klein once told the Village Voice. “But then I go to an event and there are 17-year-old girls there, and I know it’s in part because they’ve seen someone they can relate to.” When we met at a coffee shop beforehand, her demeanor was warm, if reserved, and her attention felt slightly appraising. She was funny, but her sense of humor had an edge (one friend described it to me as arch). While she was patient in her replies, I had the impression that almost every question I asked she’d heard before, perhaps more than once.

Klein has been in the public eye since 2000, when her first book, No Logo: Taking Aim at the Brand Bullies, an account of sweatshops, marketing, and the rise of anticorporate resistance, established her as a prodigiously capable systemic thinker and a writer of uncommon prescience. As she later explained on C-Span, when she would tell people she was writing a book about anticorporate activism, they would respond, “What anti- corporate activism?” “This was the ’90s,” she said. “This was the boom years.” But the book, with its explicit critique of free trade, was at the printer when upwards of 40,000 activists convened on Seattle in late November 1999 for raucous protests of that year’s World Trade Organization conference. It went on to be dubbed “the Das Kapital of the anticorporate movement,” and there are now over a million copies in print. Her subsequent book, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism, a scathing indictment of free-market fundamentalism as a system that just further enriches the already rich, was published in 2007. A year later, the U.S. economy collapsed. “If that book had come out in 2009, it would have been an explanation of everything that was happening,” says Avi Lewis, Klein’s husband and frequent collaborator. “Instead, it was like a foretelling.”

More recently, Klein has focused on climate change. “People sometimes ask, ‘What’s your next thing?’ ” she said at the coffee shop. “I’m like, ‘There’s no other issue. This is it.’ ” The central thesis of this work is that our economic system has put us on a collision course with the planet’s natural systems, and that in order to stave off crisis, we must embrace widespread economic and social change. When she took this up as a subject, there was relatively little grassroots environmental activism. But the same week that her 2014 book, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate, was released, an estimated 600,000 people participated in the People’s Climate March—the largest such demonstration in history. And her new book, On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New Deal, a collection of essays and speeches addressing climate change, came out on September 17, six days before the United Nations Climate Action Summit in New York. “She’s a visionary,” says the playwright Eve Ensler, a friend of Klein’s. “I can’t think of anyone except maybe Noam Chomsky who has the ability to see the big picture the way Naomi does.”

Klein not only spotted the early stirrings of the reinvigorated green movement but helped shape it, too. Varshini Prakash, a cofounder of the Sunrise Movement, which kicked off the push for a Green New Deal last fall when the group occupied Nancy Pelosi’s office, told me This Changes Everything was “a hugely important book to understand the connections between climate, the economy, and social justice.” Sam Knights, who helped establish the Extinction Rebellion, a UK-based group that organizes often theatrical acts of civil disobedience to raise awareness of climate breakdown, told Britain’s The Times it brought him to tears. “It was almost a physical, visceral response to this emergency,” he said. The environmentalist writer Bill McKibben, a friend and colleague (Klein sits on the board of directors of his climate organization, 350.org), has called her “the intellectual godmother of the Green New Deal—which just happens to be the most important idea in the world right now.”

At the Bloor Street event, which is filled to capacity, this sense of urgency is palpable. “I’ve been saying laughingly to my comrades for a while, ‘What an incredibly exciting and exceptionally terrifying time to be working together,’ ” says local organizer Maya Menezes, who introduces the speakers. But while Klein acknowledges that the challenges are immense, her speech is also optimistic. She spends much of her 42 minutes laying out the reasons that a Green New Deal–esque plan, which would invest in green infrastructure and renewable energy to transition the economy off fossil fuels and build a more equitable world, is both economically beneficial and financially feasible. The greatest challenge, she adds, is hopelessness. “It’s a feeling that it’s all too late [and] that we aren’t good enough to do this,” she says. “But something is shifting.... The center is collapsing, yes, and the right is rising to fill that vacuum, but they are not the only political force that is surging—there is also us.”

The question of how to maintain hope in the face of climate change was what I’d most wanted to ask Klein. Last October’s report from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change declared that due to human-caused climate change, the world was on track to hit 2.7 degrees of warming above preindustrial levels by 2040, worsening drought, wildfires, and poverty for millions; at least 50 million people alone could be displaced by coastal flooding. It went on to state that only by cutting our greenhouse gas emissions in half by 2030 could we avoid further warming. And it can be hard to imagine that this is possible, for reasons that go beyond the entrenched power of fossil fuel companies. In May, for example, ABC’s World News Tonight covered the new English royal baby more in a week than it had covered climate change in all of 2018.

In her books, Klein recognizes that the difficulties are immense, but also suggests they can still be overcome, like someone both mapping out the Death Star and the slim opening through which it can be destroyed. “Fear can’t be the driver,” as she said to the Guardian in 2015. When I asked her about her relationship to all this at the coffee shop, though, she was less sanguine than she was in her speech. “I have some hope,” she said. “I [also] have a lot of raw terror. I don’t like the word hopeful. I mean, I’m not even primarily scared of climate change. I’m scared of what scarcity looks like in a culture and economic system as brutal as ours.” The question we all face now, she went on, is whether we’re going to hoard and fortress, or find new ways to live together. “So yeah, my relationship with hope, I mean, honestly, I’m not in a terrific place with it. But I just feel like, What are you going to do? I’ve got a kid, you know? Do you just give up?”

Klein has never liked marching and has described herself as physically incapable of chanting, but she has become increasingly involved in climate activism. In 2011, she was arrested for the first time, protesting the Keystone XL pipeline outside the White House. She was instrumental in developing the divestment movement, which has led to $8 trillion being disinvested from fossil fuels. She also helped organize The Leap Manifesto, a document written in 2015 by a coalition of indigenous leaders, environmental activists, and union heads based around what Klein later described as a key insight: that many progressive battles could be addressed through a so-called “Marshall Plan for the Earth.” In late October 2016, she flew from Toronto, where she’s lived much of her life, to Australia to receive the Sydney Peace Prize for her climate work. (The irony of accepting a prize for work combating pollution by causing more pollution through flying was not lost on her, and she considered turning it down.)

Klein endorsed Bernie Sanders during the U.S. primary (Klein’s parents were both born in America and she is a citizen of both Canada and the U.S.) and often criticized Hillary Clinton for her corporate connections, but a Donald Trump presidency was unthinkable. Three days after his election, at the beginning of Klein’s acceptance speech for the prize, she apologized if it seemed rushed. She’d known she should prepare two versions, but “I couldn’t quite bring myself to write the ‘Trump wins’ version,” she said. “My typing fingers went on strike.”

Afterward, however, she got to work, writing a new book, No Is Not Enough: Resisting Trump’s Shock Politics and Winning the World We Need, in three frenzied months. “I was a woman possessed,” Klein said to the Globe and Mail. Though, she added, “I really shouldn’t say that in interviews.” Her fear was that in the event of a major shock, Trump, whom she saw as a “pastiche of pretty much all the worst trends of the past half-century,” would follow the playbook she’d documented in The Shock Doctrine and exploit the subsequent public disorientation to institute vast changes. Her hope was that alerting people to this possibility might help combat it. (A short film about The Shock Doctrine produced by director Alfonso Cuarón, who was so inspired by the book he worked for free, ends with the phrase “Information is shock resistance. Arm yourself.”) But No Is Not Enough is grim when it comes to climate change. “In four years, the earth will have been radically changed by all the gases emitted in the interim,” she writes. “And our chances of averting an irreversible catastrophe will have shrunk.” Given the possibility of a world warmed by 7 degrees Fahrenheit—which we could hit as soon as the end of the century if emissions continue at the current rate—she quotes a climate scientist who says that the result would be “incompatible with any reasonable characterization of an organized, equitable, and civilized global community.”

The night of the election, Klein’s father had texted her, “Aren’t you glad we already moved to Canada?” But since then, in a reverse commute of sorts, Klein, Lewis, and their son, Toma, relocated to New Jersey, where last fall Klein was named Rutgers University’s first Gloria Steinem chair in Media, Culture and Feminist Studies. A week after her Toronto talk, I visit Klein in her Rutgers office, which has elegant arched windows and is filled with books. She explains that the move was partly for Toma, who’s on the autism spectrum. “I feel disloyal as a Canadian, but the public school system here is better, especially for kids like him,” she says. In Toronto, he’d been in a class with 29 kids. In New Jersey, he’s in a class with only five.

Toma’s diagnosis is similar to that of Greta Thunberg, the 16-year-old Swedish climate activist who launched the school strike movement and has corresponded with Klein. (In a blurb for On Fire, Thunberg writes that Klein’s work “has always moved and guided me. She is the great chronicler of our age of climate emergency.”) “One of [their] challenges has to do with social skills, because they don’t have the impulse to mirror,” Klein says. “But in the context of climate change, that tendency is a disaster. One minute we think the house is on fire, but if it were, why would everyone be talking about facial contouring? Something I find so moving about Greta is that she shows that if someone yells ‘Fire!,’ all these folks who are neurotypical start trusting their original reaction.”

Climate activist @GretaThunberg on the #1 thing people can do to help mitigate climate change.

Extended interview: https://t.co/Fxm575fEtw pic.twitter.com/l63QEcjYhG— The Daily Show (@TheDailyShow) September 12, 2019

Once we’re done talking, Klein drives me to the train station in her white Prius. She avoids red meat but eats fish, and she brings her own grocery bags to food stores. She also flies less than she used to, but she still flies. “I’m not making a fetish of my lifestyle,” she says. Which is partly because she believes such changes will never be enough. Neither does Klein want to give the impression that buying greener products is sufficient. (One answer people often don’t want to hear: Buy less.) “I really do believe that this is not going to be solved without regulation,” she says. But details about Klein’s life have also been used to suggest she’s a hypocrite. Michele Landsberg, Klein’s mother-in-law, herself a well-known feminist journalist in Canada, recalls that after No Logo became successful, a reporter went through Klein’s garbage. “Is she supposed to wear burlap?” Landsberg says. “Did they expect you could live in consumer capitalism and not consume anything?”

One thing noted by multiple people I spoke to about Klein was that they find it surprising that she’s often referred to as polarizing. “In fact, she has this unbelievable nurturing underside, and there’s such a spiritual bent to her work,” Ensler says. “We could spend hours talking about our love of trees.” Over the course of Klein’s career, though, she’s often been willing to make herself a “lightning rod for important, controversial discussions,” says Louise Dennys, her longtime book editor, and she’s been attacked by people all over the political spectrum. On the right, she’s been referred to as a far-left ecosocialist, while socialists have said her analysis of capitalism doesn’t go far enough (Klein critiques deregulated capitalism but doesn’t go so far as to say we need to get rid of capitalism altogether). Meanwhile, a piece that appeared on the website of the ecomodernist Breakthrough Institute denounced Klein’s “everythingism—her conviction that everything is threatened, that everything must change, that everything is settled about how to change.”

But while Klein can be peevish about criticism (“p.s. BTW, you do know I didn’t write the headline, right? Just checking, cuz you seem to know so much,” she wrote in one response), she often just ignores it, rebuts it, or lightly corrects the record. After an article noted that she had a plastic playhouse at her Toronto home “that was probably made in China,” Klein tweeted that it was a hand-me-down. And in 2014, despite having recently found herself in the midst of a Twitterstorm for her claim that long-established environmental groups had been more damaging to climate change than climate deniers, she told British magazine The New Statesman that her greatest difficulty on Twitter was being confused with the controversial author Naomi Wolf. I made this same mistake last May when I read that Wolf, in the midst of an interview, had discovered that the central premise of her new book was incorrect—for a brief, disorienting moment, I existed in a reality where global warming wasn’t actually a problem. Not long after, referring to the incident with Wolf, Klein reposted a tweet that read, “The real victim in all this is Naomi Klein.”

Klein has always had a clear sense of right and wrong. As a teenager, she also loved makeup and going to the mall. She got a job at Esprit because she thought they had the best logo (though she was fired for having a bad attitude); her high school yearbook described her as the girl “most likely to be in jail for stealing peroxide.” “I was just an average kid in the ’80s,” she says. But this put her at odds with her parents, staunch leftists who had moved to Canada from the U.S. before she was born to avoid the draft. (Klein also has an older brother and an older half sister.)

The family settled in Montreal, where Klein’s father, Michael, worked as a pediatrician at a public hospital and her mom, Bonnie, became part of Studio D, a state-sponsored women’s film studio, producing documentaries, most notably Not a Love Story, a critique of pornography that proved controversial not only for its message but for its inclusion of hard-core imagery. (A young Klein appears, briefly, her hair tied up in a ribbon, walking into a corner store that happens to have X-rated magazines for sale.) It came out in 1981, when Klein was 11, a scenario that “was not ideal from the perspective of a preteen,” Klein explained on C-Span. As her mom later wrote in a Ms. magazine essay, “Conflicted by her mother’s highly visible feminism, [Naomi] has asserted her individuality by learning the skills of femininity.”

Klein often felt judged by her parents, and they fought frequently. “Both my parents were free spirits, especially my mom,” Klein says. “I keep a fairly tight lid on things.” But their relationship shifted the summer Klein was 17, when her mother had two strokes. (Bonnie was initially immobilized but eventually became able to walk with two canes.) “Now there would be no more bull between my mom and me,” Klein writes in her mother’s memoir, Slow Dance. “We would stop fighting and be allies.”

At the University of Toronto, Klein focused on journalism. At one point during the Palestinian uprising known as the First Intifada, she wrote an article for the student newspaper that criticized Israel and subsequently received bomb threats, but she still went to the meeting organized around it by the Jewish student union, which she knew opposed the piece. “The woman sitting next to me said, ‘If I ever meet Naomi Klein, I’m going to kill her,’ ” Klein recounted to the Guardian in 2000. “I just stood up and said, ‘I’m Naomi Klein…and I’m as much a Jew as every single one of you.’ I’ve never felt anything like the silence in that room.”

So glad to finally meet! @NaomiAKlein #ourclimatefuture pic.twitter.com/aKCzeQBKM9

— Greta Thunberg (@GretaThunberg) September 9, 2019

After three years, Klein dropped out to take a job at the Globe and Mail, then became editor-in-chief of the left-leaning This Magazine. But eventually she decided there wasn’t enough of a left to even report on, and returned to college in 1996. By then, she was dating Lewis, who was working as a host on MuchMusic, Canada’s version of MTV, and who also came from a family of well-known leftists (his father is Stephen Lewis, a prominent member of Canada’s social democratic New Democratic Party; his grandfather led the party during the 1970s). “He said to me, ‘It’s incredible, Ma, we even grew up singing the same folk songs!’ ” Landsberg says.

Klein moved into Lewis’s warehouse loft, then dropped out of college, again, to work on No Logo. They ended up spending part of their honeymoon in Jakarta, Indonesia, so that Klein could interview Nike workers. (Today they remain a symbiotic-seeming couple—after I asked Klein if I could speak with Lewis, he responded with an email whose subject line read, “Chatting about my favorite subject!”)

Klein launched No Logo at the same Bloor Street church she spoke at last June. Once the book became a worldwide sensation, she found herself traveling the world to report on the anarchic, diffuse movement she’d foreseen and give talks about it. Lewis recalls being in Italy with Klein as photographers walked backward shouting, “Miz Klein! Miz Klein!” No Logo’s success meant Klein was pressured to follow it with a similar book; instead, she moved to Argentina with Lewis to film The Take, a documentary about the country’s worker uprising. Since then, Klein has reported from Iraq during the U.S. occupation, post–Hurricane Katrina New Orleans, Standing Rock, and so many other places she can almost seem to be some sort of progressive superhero, popping up wherever crisis occurs. Klein, however, would dislike this analogy—she worries about such a narrative even when it’s applied to the young people bringing fresh energy to environmentalism. “No one’s coming to save us,” she says. “We’re on our own, and we have to save ourselves.”

Klein first became interested in writing about climate change in 2009, when Angélica Navarro Llanos, Bolivia’s ambassador to the WTO, explained that it offered a strong argument for economic reparations from wealthier countries to poorer ones, who will bear the brunt of global warming yet have done the least to cause it. “I was like, ‘Oh, climate change isn’t just an environmental issue, it’s an economic justice issue,’ ” Klein says. “Why have you been sitting this out?” she says of the left during a 2014 Grist interview. “This is the best argument you’ve ever had.” (This approach also opens her to critique: “The ideas associated with climate change are so broad, complex, and plastic that pretty much any ideology can [use them] to endorse their vision of the world,” says Mike Hulme, a professor of human geography at the University of Cambridge. “That’s as true for Naomi Klein as it is for the rest of us.”)

Another pivotal moment in Klein’s thinking about global warming was when she went to Copenhagen for the 2009 UN Climate Change Conference. “Obama had just been elected, and there was this drumbeat of, ‘Are we going to solve global warming now?’ ” says journalist Johann Hari, a friend who was there with her. “Instead, the leaders of the world looked at each other, shrugged, and walked away.” The experience was devastating for Klein. Back home, she learned of a new poll that found that among Americans, belief in human-caused global warming had dropped from 71 percent to 51 percent in two years. This Changes Everything grew out of her attempt to answer how this could have happened.

While she reported it, she was also trying to get pregnant. For years, Klein had been ambivalent about having children, partly because of global warming—“I imagined him like a Mad Max warrior fighting with other kids for water”—but also because it didn’t seem possible with her life. At one point, while reporting The Shock Doctrine, she and Lewis drove overnight across Sri Lanka on a pothole-riddled road, in a van without shock absorbers. “You know what would be even better than doing this?” Klein asked him. “Doing this with a six-month-old.” By the time she started trying to have a baby, she was in her late thirties, and she had multiple miscarriages before giving birth to Toma. Then two years later, as This Changes Everything was about to come out, Klein was diagnosed with thyroid cancer, which was treatable, but left her with a scar on the side of her neck and a topic she’d rather not discuss in interviews.

These days, Klein thinks constantly about Toma’s future. “It obsesses me,” she says. She’s also deeply aware of the stakes of the next election. As she writes in her new book, “As our societies fail to act like our house is on fire, the house does not just sit there burning like some sort of fixed, looping GIF.... Irreplaceable parts of the house actually do burn to the ground. Gone, forever.” She continues to try to spread awareness of the alternatives that remain before us and to enable a broader discussion of what’s possible. In On Fire, for example, she quotes author Ursula K. Le Guin: “We live in capitalism, its power seems inescapable. But then, so did the divine right of kings.” Though sometimes Klein also worries she’s just helping people fail with open eyes. “For Naomi, hope is not a passive thing,” Hari says. “But what is it like to see there is an alternative? I think the grief is all the greater precisely because it doesn’t have to happen.”

As Klein explained in her Sydney Peace Prize speech, while in Australia she’d taken the opportunity to bring her son to visit the Great Barrier Reef, along with a Guardian film crew, who produced a short video. In it, Toma, four, appears in the water, wearing floaties, peering down into the deep as Klein and a diving instructor hold on to his arms. Already, a quarter of the Great Barrier Reef was dead—Klein describes those areas looking like they’d been passed over by “an angel of death”—but the portion she visited with Toma was alive, and he saw “Nemo” and a sea cucumber. That night, tucking him into bed, she tells him, “Toma, today is the day when you discovered there is a secret world under the sea.” What happened next made her burst into tears. He looked up at her, his face an expression of bliss, and said, “I saw it.”

You Might Also Like