The Prison Program Healing Lifetimes of Pain

From the outside looking in, Sue Lambert appeared to be a strong, capable, resilient woman. When her marriage fell apart, she took their 7-year-old daughter and left—never mind that she was nearly 40 and had only a high school education. She got a job as an assistant at a property management company. Zoomed up the ladder. Eventually owned her own firm. It oversaw a large homeowners association and came to earn her nearly $200,000 a year. Lambert bought a house, her dream cabin in the mountains. When her lifelong struggle with obesity forced her into two knee replacements by age 50, she faced the hard truth: She was never going to lose the weight and keep it off by dieting alone. So she braved gastric bypass surgery, lost 150 pounds, and hit a decent BMI for the first time in her adult life. As she headed into her 60s, Lambert seemed to not only have it all but have earned it all. Especially the important stuff. The respect of those she worked with. The affection of her friends. The love of her daughter.

From the inside looking out, though, the view was very different. Lambert didn’t know what was wrong with her, but she was sure something was—something very bad that had always been there. She had begun drinking at the age of 11 and had alcohol use disorder by the time she was a teenager. Except for the year or so she was pregnant and breastfeeding, she downed a good quart of hard liquor (or the equivalent thereof) a day—most every day. Those knee replacements, they hurt. Doctors prescribed oxycodone. Soon, she was hooked. When she felt kind of pretty for the first time in her life after the gastric bypass surgery, Lambert bought herself some nice outfits and started going with friends to a casino that had opened not far from where she lived in Northern California. In a way, those nights at the slot machines were fun. In another way, they were the epitome of the wasted emptiness she’d felt her whole life. At first, Lambert let herself lose only $400 per visit. But soon she was hitting a casino ATM for more cash most every visit. Within a year, Lambert didn’t have enough money to pay for things like her mortgage.

A contractor she worked with had an idea to solve that problem: Create fake work invoices for the homeowners association she oversaw. They’d split the proceeds. Lambert told herself she’d pay the money back. Instead, she started using her company credit card for personal stuff—specifically, her gambling expenses. It wasn’t enough. At age 62, Lambert filed for bankruptcy. She lost her cabin, her home. The association she managed figured out she’d been stealing and fired her. Turned out Lambert had dropped $1,081,827.36 at the casino.

Lambert’s bankruptcy attorney referred her to a criminal attorney. Explaining she could face more than seven years in prison, the lawyer started laying out a strategy to fight the charges. Lambert cut him off. She didn’t want to fight them.

In 2015, at age 64, Lambert stood behind a table in a San Mateo, California, courtroom. Superior Court Judge Elizabeth K. Lee asked if she was there to turn herself in for embezzlement, forgery, and grand theft.

“Yes,” Lambert said.

“Put your hands behind your back,” said one of two deputies behind her. Lambert did. As she was handcuffed, she turned toward the gallery, where her 37-year-old daughter was sitting. Each gave the other as brave a smile as they could muster. Then the deputies led Lambert away to have her mug shot taken and be transported to San Mateo County jail. As she got into her orange jail scrubs, Lambert had a thought: While I’m in here, I’m either going to figure out what’s wrong with me or I’m going to accept that I’m just defective. Accepting the latter, she knew, meant a life sentence of self-hatred.

San Mateo County jail didn’t offer a lot of self-improvement programs, but Lambert signed up for everything she could. The first was a grammar course; she wound up the teacher’s aide. The second was a kind of anger management class. Unfortunately, the class didn’t help her get in touch with her anger—which she learned later that she had a lot of. The third was called the Enneagram Prison Project (EPP) Self-Awareness Training Program.

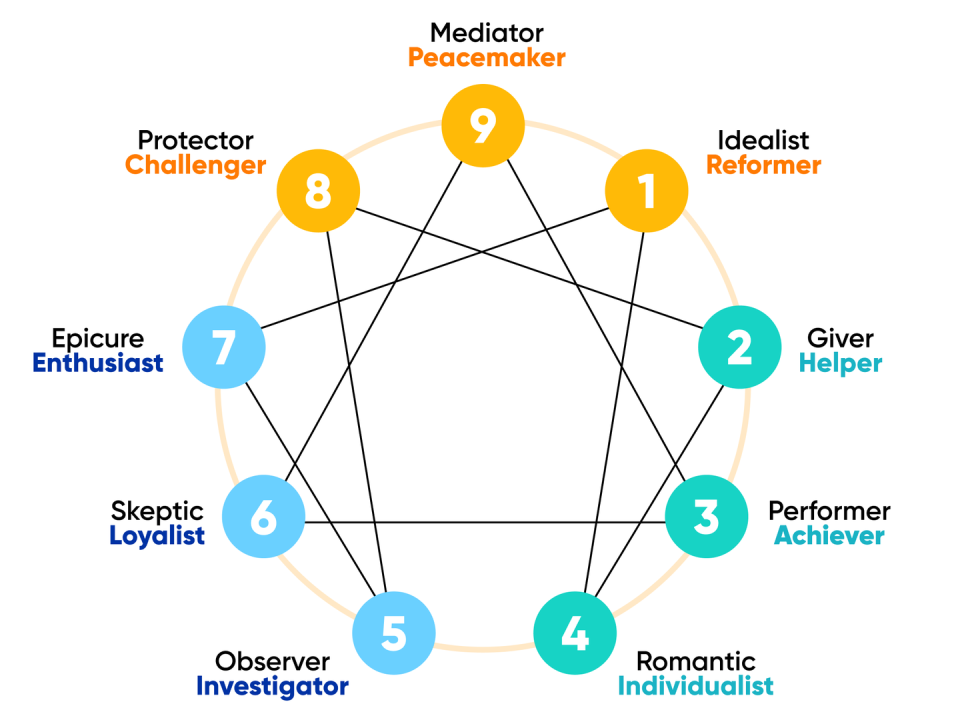

The Enneagram turned out to be a geometric figure—a triangle overlaid with a weird-shaped hexagon, both inside a circle. The inner shapes create nine points, each of which the Enneagram system says corresponds with a personality type. Some compare the Enneagram to commonly used personality tests, such as the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator or the Caliper Profile. Others say it’s a lot more like astrology. Some say it’s a powerful tool for personal development; others dismiss it as pseudoscience. Lambert thought its symbol-thing looked like witchcraft. But she was desperate, so she signed up.

The 9 Enneagram Personality Types

Lambert wound up taking the eight-week, eight-module course five times. In all that time, in doing all that work, Lambert never figured out what was wrong with her. She did, however, learn what was right.

The gist of Enneagram theory is universal: We’re all born with a “divine spark,” but, because no one has a perfect childhood, we all lose touch with it. As our needs go unmet, we develop cognitive, emotional, and behavioral patterns. In other words, our personalities form as an amalgam of our innate natures and our efforts to cope with whatever nurturing we lacked and violations we suffered.

While every human being is unique, there are nine Enneagram types or personalities. (See diagram above.) No type is better or worse than any other; however, each one has distinct core motivations and fears. The theory is that people who study their type become more mentally, emotionally, and spiritually healthy. They can even reconnect with their divine spark, which was inside them all along.

It gets way deeper from there. If you want to dive in, one place to go is the Human Potentialists, a.k.a. THP, a benefit corporation that serves social and environmental justice.

Susan Olesek is the founder of the EPP and THP. She first learned about the Enneagram in a parenting class about 25 years ago. A trauma survivor herself (at age 5, when Olesek was eating dinner with her siblings one evening, her father discovered that their mother had hung herself in the basement earlier that day), she quickly felt that it could—more than therapy, more than workshops, more than the maybe dozens of self-help books she’d read—enable her to become not only the kind of mom she wanted to be but the kind of person she wanted to be. In 2009, she became a certified Enneagram instructor. Because she lived in the Bay Area, she expected to teach employees and executives at companies like Apple and Google—and eventually, she did just that. But one of the first places that invited her to come teach the program was a prison in Texas.

Olesek was daunted. She was afraid that gang members, rapists, and murderers would be far too damaged or rageful to “get it.” But the moment guards brought her to a classroom in the facility, she realized she’d been terribly wrong. “They were starving to know the truth about themselves,” Olesek says. “They shocked me with their transparency and what they were willing to admit to having done—and also [what] happened to them during their childhoods. [I learned that] when we give them this incisive psychological tool and the loving support they need to unpack what happened to them, people who have been practically thrown away, warehoused, do what hardly anyone believes is even possible to do. They begin to heal.” In short, Olesek had a major “aha moment.” Until we really understand ourselves—until we reconnect with our divine sparks—“we are all in prisons of our making,” she says. In 2012, Olesek founded the EPP and began teaching an Enneagram-based self-awareness training program she designed in any correctional facility that would let her.

The first module of the EPP’s Self-Awareness Training Program is called “What’s Right About You?” that includes an Enneagram Personality Test. There are many versions of this test. The one THP and EPP uses, the Essential Enneagram, was developed by David Daniels, MD, and Virginia Price, PhD, of Stanford University. You can take it here for $10. When Lambert took it, she learned that she’s a Type 1, the “Idealist/Reformer.” Type 1’s are extremely hardworking, hyper-conscientious, and competent. As disgusted as she was with herself, Lambert could not deny that the description fit her to a T. Nor could she deny what it said her “blind spot” was—hypocrisy.

The program’s second module is called “How We Develop,” in which students write a timeline of their lives, starting with their earliest memory. Lambert’s included the following:

Age 3 or 4: Father beats her for playing in the mud.

Elementary school: Father either comes home drunk and violent or is gone for days at a time.

Age 7: Mother, who doesn’t drive, starts taking two buses to a secretarial job. Lambert is left alone from about 5:30 a.m. to 7:30 p.m.

Age 8: Not enough food in the house.

Age 11: Molested by friend’s father’s friend.

Age 11: Starts drinking alcohol.

Age 13: Sees father with another woman and young boys, discovering he has a secret other family.

Age 16: Mother takes a job in another city, leaving Lambert to pay her own rent and live on her own.

After EPP students finish their timelines, they learn about how our childhoods not only affect but also shape us. Neuroimaging shows that early-in-life trauma can disrupt healthy brain development, but the good news is that the brain is wired to survive. The Enneagram system says that the brain actually has three emotional alarm systems that activate when—despite what our parents or caregivers might tell us, despite what we might even tell ourselves—we perceive that our needs are not being met. For Enneagram Types 8, 9, and 1, the emotional alarm is anger or rage; for Types 2, 3, and 4, the emotional alarm is grief or shame; and for Types 5, 6, and 7, the emotional alarm is fear or terror.

Lambert knows this will sound nuts to a lot of people (maybe especially Oprah Daily readers), but until she learned the Enneagram, she never thought her childhood—being beaten, molested, and abandoned—had anything to do with her adulthood. “I just felt like that was my school of hard knocks. Get over it,” Lambert says. But suddenly her Type 1 perfectionism and hiding in a body with obesity until that body literally started giving out didn’t seem like random defective behaviors. Rather, they appeared to be acts of desperation. “Finding out they were connected was a jaw-dropping moment for me,” Lambert says.

It was also a breakthrough. As Daniel Siegel, MD, the founding codirector of the Mindful Awareness Research Center at UCLA, says, “Making sense of a past that made no sense is how you can free yourself to live the life you want now.”

The course’s third module is simply called “Addiction.” The EPP really drills into that topic because research shows that about 85 percent of incarcerated people have or have had substance use disorders. The fourth, fifth, and sixth modules of the EPP are deep dives into the system’s nine types of personalities. They describe the key characteristics, ego fixations, basic fears, basic desires, survival strategies, defense mechanisms, blind spots, and red-flag fears of each Enneagram type. And the course’s seventh module covers each type’s defense mechanisms.

In the eighth and final module of the EPP, students reflect on how learning self-awareness through the Enneagram system has changed them.

Lambert says she wasn’t changed during the nearly two years she spent behind bars, studying the Enneagram—rather, she was “transformed.” Just as she became an official senior citizen, she began to understand herself. That understanding freed her from the compulsion to do self-destructive, hurtful things. And that freedom gave her grace—to find her personal purpose, meaningfulness in her life, and even self-love, which, paradoxically, is the opposite of egotism that used to drive her to super-achieve.

Upon her release from jail, Lambert happily took a job folding shirts at a Target. She also began studying to be an Enneagram teacher and an EPP Ambassador.

Olesek describes the Ambassadors as “the heart of our project.” They are people who, through the EPP, “found personal inner freedom while incarcerated.” And, after being physically freed from custody—as well as becoming emotionally and economically stable “on the outside” (which is often as hard as anything else they’ve had to do in their lives)—they go back to jails and prisons, often to the very facilities at which they did time, to teach the EPP Self-Awareness Training Program to people currently behind bars. Since 2012, the EPP has been taught in 30 correctional facilities around the world—literally, every place that’s let Olesek in, including California, Colorado, Illinois, Minnesota, Kentucky, and Washington State—as well as Canada, Belgium, France, and the U.K. So far, 3,743 students have graduated from the program.

Last year, Lambert taught the EPP Self-Awareness Training Program at San Mateo County jail, the very facility where she’d done time. She was shocked to see Judge Elizabeth Lee—the judge who’d sentenced her—among them. At the end of the ceremony, the judge asked if she could say a few words.

“Of course,” Lambert said.

The judge took out a piece of paper. It was a letter Lambert had sent her years earlier while she was in custody. Judge Lee read aloud one of its last paragraphs.

“I will always have remorse for my bad decisions, for the people that I hurt, and those who trusted me and I let down,” Lambert had written. “I set up my restitution payment that I will expect to pay forever. I have faith that my service to other suffering human beings is also a way to give back to our world. I hope that if I, or my story, can help one person change, then my experience will be of service to the world.”

The judge then said that the EPP graduates were absolute proof that Lambert’s experience has been of extraordinary service to the world.

The last time we spoke, I told Lambert how much her story had personally touched me, and that I was sorry for all the suffering she’d endured.

She was silent for a long moment. Then she said, “Through the transformation of all the ‘work,’ I don’t look back thinking If I only knew, my life could have been different. I look back and say, Thank God for the path to get here.”

As I’m writing that down, Lambert tells me she needs to get off the phone. She’s heading into a prison—the place, she says, she knows she belongs.

You Might Also Like