'Princess Diaries' Author Meg Cabot on the Witchy Inspiration Behind Her New Book

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

My mother was born on Friday the 13th, earning her the family nickname of Jinx. Naturally, as a kid, I assumed this meant my mother was a witch.

I was over the moon about this. A fan of Sabrina the Teenage Witch, I was sure that I would inherit mom’s witchy powers one day, and then be able to cast spells, fly and bend my enemies to my will.

Alas, that day never came. There was a problem: my mom wasn’t actually a witch. When I finally asked her about it, impatient to know when my powers would show up, Mom not only denied possessing any supernatural powers whatsoever; she insisted she’d never done anything remotely magical.

As much as I loved my mom exactly the way she was, I was disappointed. It’s human nature to romanticize our family history. Who wouldn’t want to find out they’re descended from royalty, someone famous or even — in my case — a witch? It’s been hundreds of years since an accusation of being a witch could get you tried and even executed, at least in the United States. (As recently as a decade ago, two women were beheaded for “sorcery” in Saudi Arabia.)

But now the only people who talk about "witch hunts" are politicians. To nearly everyone else, witches are considered feminist icons: empowered, glamorous and cool. It wasn’t until I was an adult — long past the age of believing in magic, but still loving its fictional allure — and had begun writing a new paranormal rom-com featuring feminist witches that I learned I might not have been so wrong about my family’s connections with the supernatural after all.

“Your great-grandmother Serafina was a witch,” my dad’s sister told me when she heard about the book. “Didn’t anyone ever tell you?”

Um, no.

My dad, who died when I was 26, had never talked much about his family. It turns out there was a reason why. His grandmother, Serafina, had immigrated to the U.S. from a small village near Naples, Italy, at the turn of the last century. There, according to my aunt, she’d “lived in a cottage surrounded by a white picket fence with a flowered vine running through it” and cured any number of neighbors and relatives of various maladies — everything from warts to migraines — with her “home remedies.” This included my science-minded dad, who was so freaked out as a child when his grandmother cured him overnight of a wart using a “magic cloth” that she rubbed lightly over his fingers, he never spoke of it (at least in front of me) again.

But there was a dark side to Serafina’s story: One of her relatives had been executed for witchcraft back in Europe, many years earlier.

This was horrifying, but not so unusual. Over three million people were tried for witchcraft in Europe between the 14th and 17th century, and at least 60,000 of them were executed for it. Most of these were women who’d been disenfranchised and had no way to defend themselves, or had inherited wealth or property that the men in their villages hoped to seize upon their death. It’s likely many of us are related to someone who was murdered in this way, just as many of us are related to members of today’s vulnerable marginalized LGBTQ+, BIPOC and immigrant communities.

But when I went to look for documentation of the trial of my unjustly executed ancestress, I couldn’t find anything. That’s because records for people — especially women — tried for witchcraft often no longer exist, not only because municipalities are ashamed of their past wrongdoings, but because these documents were so often stored in buildings that flooded, burned down or were otherwise destroyed over time.

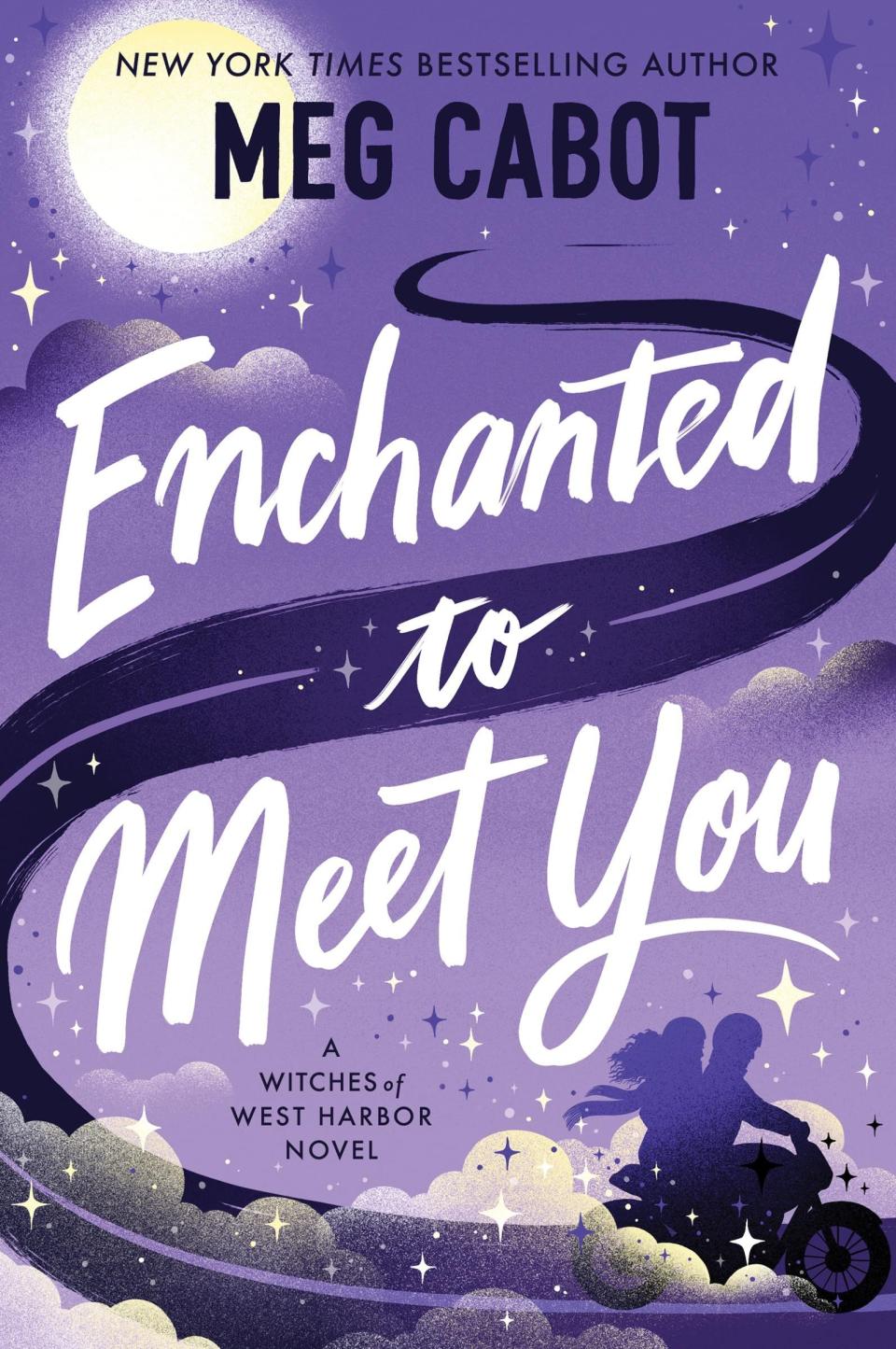

Enchanted to Meet You: A Witches of West Harbor Novel

amazon.com

$30.00

Frustrated by the realization that I was about as likely to find out what really happened to my long-dead relative as I was to magically cure someone of warts, I poured my feelings about the injustice into my book, Enchanted to Meet You. It wasn’t until I was finishing it that I got some startling news: Modern-day ancestors of people executed for witchcraft in Connecticut nearly 400 years ago had successfully lobbied to get the names of their long-deceased relatives officially exonerated of the “crime.”

Without trial records or even her name, there was no way I was ever going to be able to do this for my own relative, but I was so happy for the families who’d succeeded in getting this small piece of restorative justice for theirs. As my aunt regaled me with more stories about my own witch foremother — her beloved black mutt, cake recipes and of course “magic cloths” — I realized something important.

Despite my mother’s insistence that she’d never done anything remotely magical, she’d managed to raise three kids, all while also working part-time, earning her master’s degree and volunteering for Planned Parenthood. Just like my great-grandmother’s ability to heal, that’s not only magical, but miraculous.

And while my mom’s achievements might not be otherworldly, they’re now even more empowering to me than anything Sabrina ever did.

Meg Cabot's new book, Enchanted to Meet You, is now available from your favorite bookseller. This essay is part of a series highlighting the Good Housekeeping Book Club — join the conversation and check out more of our favorite book recommendations.

You Might Also Like