Prince Philip: A Celebration, Windsor Castle, review: an apt tribute to both sides of the Duke

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

To mark what would have been His Royal Highness the Duke of Edinburgh’s 100th birthday this month, a commemorative exhibition has opened at Windsor Castle. It bears a suitably unfussy title for a laudably unfussy man – Prince Philip: A Celebration – and features 120 objects, drawn mainly from the Royal Collection.

It begins with a brief recount of its subject’s peripatetic youth and early career in the Royal Navy. It is the Duke’s years as Britain’s longest-serving royal consort, though, that are the focus. One of the standout exhibits is the flowing robe he wore to the Queen’s Coronation at Westminster Abbey in 1953, made from a combination of red velvet and black-and-white ermine.

Shortly after the coronation, the Prince knelt before Her Majesty and swore his allegiance to her with the pledge “I Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, do become your liege man of life and limb”. Reunited with his wife, in a more private moment later in the day, he eyed her crown and asked: “Where did you get that hat?” Those respective sets of words reflect two very different sides to the Duke: the official and the unofficial; the formal and the informal. This is a dichotomy that runs throughout the exhibition.

Another showstopper is the Duke’s high-backed Chair of Estate, normally kept beside the Queen’s matching example in the Throne Room at Buckingham Palace. Made of gilded beechwood, the chairs are upholstered in crimson silk damask: his with the letter ‘P’ embroidered into the back, hers with the letters ‘ER’. They’re so ornate that the Royal couple hardly ever used them. The contrast is marked with the much-treasured bracelet on view, which the Duke designed (using diamonds from a tiara of his mother’s) and gave to the Queen as a wedding present.

This exhibition is one of two that the Royal Collection Trust is organising in the Duke’s honour this summer: the other opens in late July at the Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh. Though they cover similar ground, a key difference between the shows will be how each considers its subject’s links to that particular setting.

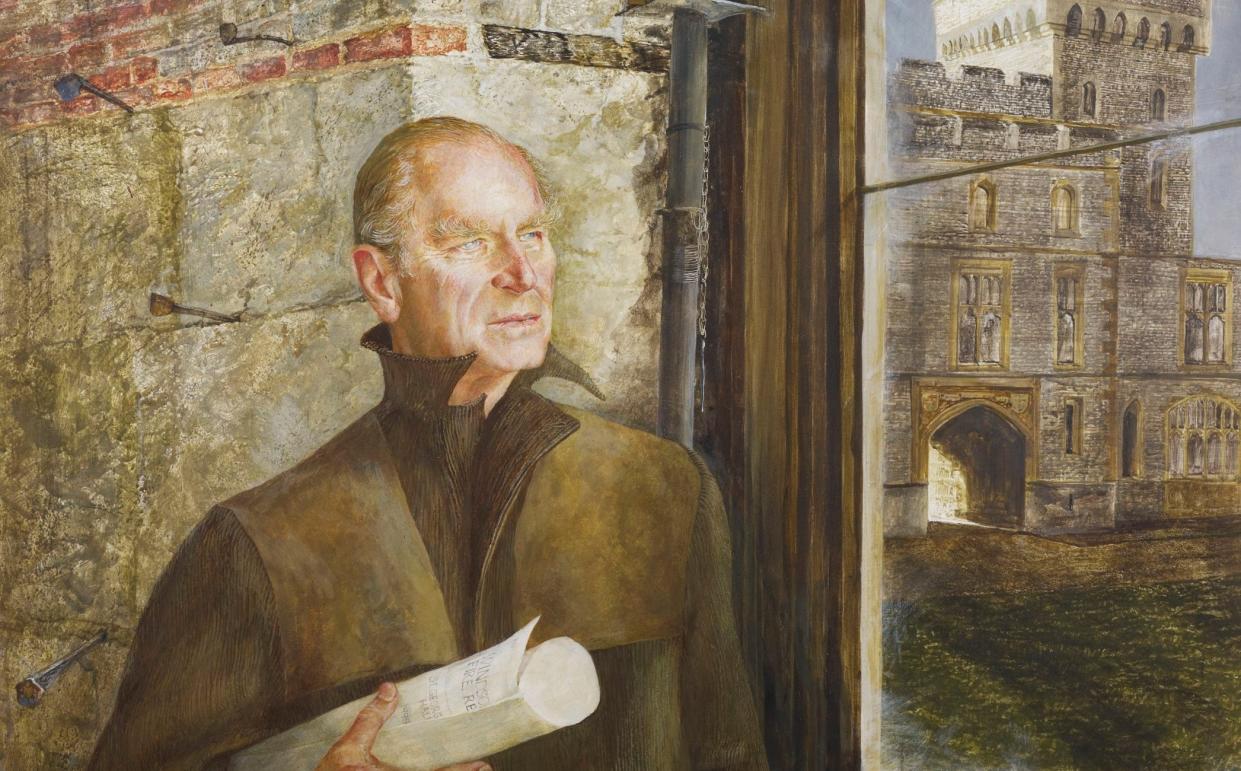

Here at Windsor Castle, a whole section is dedicated to the Duke’s close association with the residence (where his mother, Princess Alice of Battenberg, was born in 1885). He was named chairman of the restoration committee after the devastating fire of 1992. In a portrait by the American artist George A Weymouth, painted three years later, we see the Duke standing in the shell of St George’s Hall. He looks ready for the task of rebuilding – his jacket collar raised, a steely look in his eyes, a roll of floor-plans in his hand.

The Duke was a man of myriad interests, and one of the good things about this exhibition is how it nods to so many of them. His love of driving and his support for British industry are captured in a single exhibit: a steering wheel given to him by Lotus in 1979, from the car driven by Mario Andretti to the previous year’s Formula One World Championship.

We’re never in danger, however, of forgetting the Duke’s role as consort. On display are several gifts he received on state trips from foreign leaders – including a giant wine cooler in the shape of a grasshopper. More than a metre long, this was designed by the quirky French sculptor François-Xavier Lalanne, and given to the Duke by the French president, Georges Pompidou, in 1972.

I have two criticisms of this exhibition, both relatively minor: first that much of its content will be familiar to those who attended a similar Windsor Castle show, Prince Philip: Celebrating Ninety Years, a decade ago. Secondly, the seven or eight artworks depicting the Duke himself are almost all poor. In Ralph Heimans’s 2017 portrait, set in Windsor’s Grand Corridor, he bends forward with his hands behind his back and looks at us in a manner more resembling a butler than a prince.

But the artists’ struggles aren’t entirely their fault. The Duke had too rich a character and life-story to be pinned down in one image. This exhibition succeeds precisely by shedding light on so many aspects of the man. It’s a fitting and fascinating tribute.

At Windsor Castle until Sept 20 and the Palace of Holyroodhouse from July 23 until Oct 31. Tickets: rct.uk