Pregnancy Is Not Supposed to Kill Us, Yet I Almost Died — Twice.

On a crisp day in November 2017, my husband raced me to the emergency room, our newborn nestled next to me in her car seat, as I dictated my last wishes into a recording app on my cell phone.

I was 38 and in tremendous pain. Please, God, I thought, don’t let me die. I need more time with her. I had already lost a baby to an ectopic pregnancy before conceiving this one, a terrifying, emotionally devastating experience that almost killed me. And now this.

Less than a month earlier, I’d given birth to Madeleine Grace at the hospital to which we were headed, near our home in New York’s Hudson Valley. My pregnancy had been uneventful, but the delivery was far more dramatic: I had an emergency C-section after the baby didn’t respond well to the drug I was given to speed up my labor. Mercifully, my sweet Madeleine was born perfect and screaming with life. As they examined her and sewed me back together, I was overcome with relief. The worst was behind us — or so we thought.

But one night three weeks after her birth, I felt a sharp pain beneath my ribs. I thought it was just gas, or maybe a pinched nerve. When I struggled to breathe on the second day, my husband and I suspected a panic attack. The breathing difficulty abated, but the pain persisted, evolving into a mysterious, crippling agony of body and mind. An on-call doctor at my ob/gyn office, seeming unconcerned, told me that because I was no longer pregnant, I wasn’t their practice’s concern anymore and directed me to call my primary care doctor. She was out, so I saw another doctor in the practice, a man who looked to be in his 60s or 70s. “You’re an older mom,” he said in a tone that felt somehow accusatory. He chalked up my pain to a likely torn muscle. Two days after that, I was coughing up blood into my bathroom sink.

Luckily, my regular doctor, a fellow mom, was back by then. “You need to get to the ER immediately,” she said. “This sounds like it could be a pulmonary embolism.”

ALL TOO COMMON

A pulmonary embolism involves blood clots that journey from the legs or other body parts through the heart before getting lodged in an artery in the lungs. If left untreated, the condition carries a mortality rate of up to 30%.

That’s how I found myself readmitted to the hospital, in fear for my life. Tests confirmed that blood clots had been tearing through my core, killing lung tissue. I now know that pulmonary embolism is one of the most common causes of pregnancy-related death in the U.S., responsible for about 10% of cases. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), women are five times as prone to blood clots while pregnant, and a C-section nearly doubles that risk; the most dangerous period is during the first weeks after childbirth. Such cases fold into dismal CDC statistics indicating that more than 50,000 women in the U.S. annually face a range of serious and sometimes long-lasting pregnancy and childbirth complications. I am one of the fortunate ones, unlike the roughly 700 American women who die each year, a disproportionate number of whom are people of color.

WHY HERE, WHY NOW?

America’s maternal mortality rate is significantly higher than that in other high-income developed countries. While 20.1 deaths per 100,000 live births may not sound like a lot, consider this: Having a baby here, in the richest country in the world, is more dangerous than in less wealthy places like Kuwait and Kazakhstan. While the worldwide maternal mortality rate fell about 38% between 2000 and 2017, U.S. numbers are actually getting worse, more than doubling over the course of three decades.

Of those deaths, the CDC found that about a third occurred during pregnancy, a third happened during or within a week of delivery and the remaining third happened up to a year postpartum. The most common causes are cardiovascular conditions, infections or sepsis, hemorrhaging and embolisms. “A mother or mother-to-be dies every 12 hours in the U.S.,” former U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams said in a December 2020 press statement.

Worldwide maternal mortality rates are falling. In the U.S., they’ve more than doubled over three decades.

Experts have been pointing to a rising crisis for years. ProPublica and NPR copublished their lauded “Lost Mothers” series the year my daughter was born. Several high-profile Black moms, including Beyoncé and Serena Williams, forced the subject into mainstream headlines following their own close calls. The Black Lives Matter movement helped put a spotlight on all facets of institutional racism in the U.S., including the disproportionately devastating maternal health outcomes in communities of color.

But tangible progress, in terms of targeted legislation and health care reform, has been painfully slow. Efforts at passing federal maternal mortality–related legislation in March 2020 were hampered by the onset of the pandemic.

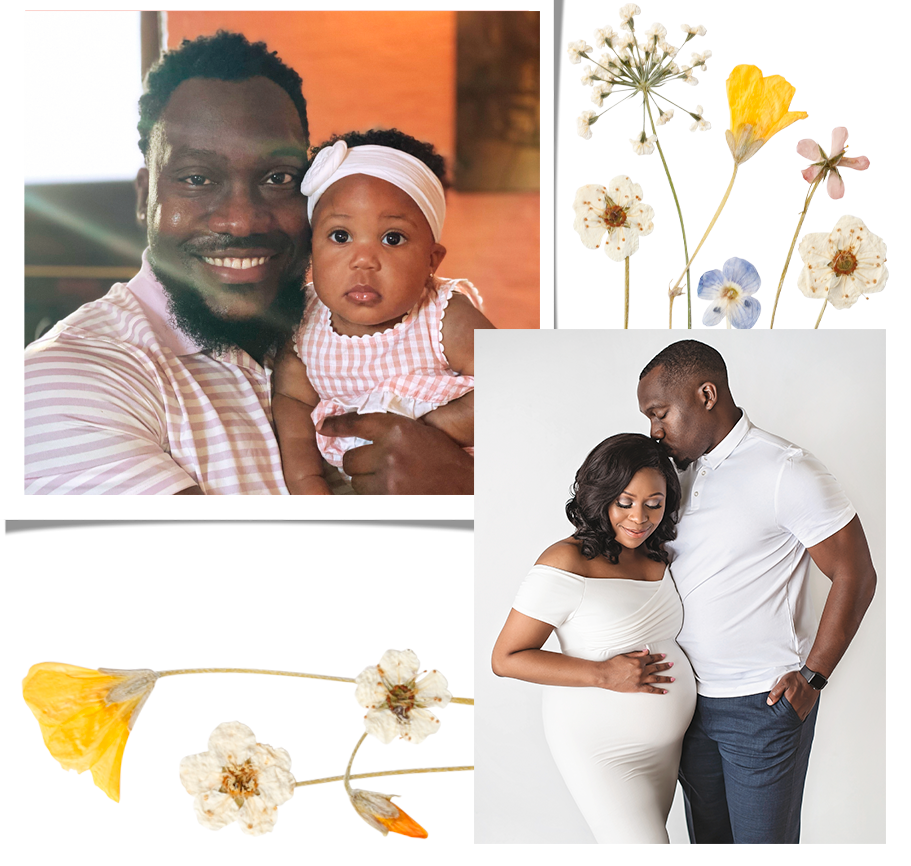

Yet for moms, the consequences keep coming. Thirty-year-old Chaniece Wallace, M.D., an Indiana pediatrician, was added to the head count of lost mothers in October 2020. She died just two days after she and husband Anthony Wallace welcomed Charlotte, their first child. Charlotte arrived a month premature, via C- section, following her mother’s preeclampsia diagnosis. (Preeclampsia is a serious pregnancy condition that arises in about 3% to 7% of pregnancies; it is characterized by high blood pressure and liver and kidney damage.) Anthony Wallace recalls that Chaniece’s pregnancy had been uneventful until signs indicative of preeclampsia arose in the weeks prior to her passing. “She was so ready to become a mother,” he says. “We just imagined the different possibilities that Charlotte would grow up to be.” Of course, neither imagined that their daughter would grow up without her mother.

Dr. Chaniece Wallace’s death underscores the disparities in maternal health outcomes for women of color in the U.S. According to the CDC, Native American and Black women are two and three and a half times as likely, respectively, to die from pregnancy-related complications as white, Hispanic and Asian women. Data indicates that higher income and education levels make little difference — college- educated Black women are 5.2 times as likely to die from pregnancy-related complications as their white counterparts. Anthony says, “I believe that [what happened to Chaniece] was partially because of her ethnicity.” Now, as little Charlotte gets ready to celebrate her first birthday, Anthony is raising her as a single dad, without his wife by his side. Arranging child care and making sure he cares for himself are big challenges, he says, “and just making sure I’m having time to process my wife’s death.” His loss hits him hardest during Charlotte’s nightly bedtime routine. “I think that putting a child to bed has always been a very intimate piece of parenthood — just the idea of tucking a child in or reading them a bedtime story, singing them a melody,” he says. “I just wish she was here to share in those moments with me. With Charlotte.”

Then there are the tens of thousands of survivors of “severe maternal morbidity” such as I, those who experience serious medical issues related to pregnancy and childbirth like clotting and bleeding, hysterectomy, acute kidney failure and sepsis. For every pregnancy-related death in the U.S., 70 women come close. “We all know someone, whether it’s ourself or our sister or our best friend or our neighbor,” says Rep. Lauren Underwood (D-IL), cofounder and cochair of the House of Representatives’ Black Maternal Health Caucus. “It’s something that unfortunately unites so many birthing people and families around the country.”

I share such survivorship bonds with my college roommate, Katie Erickson, 44, of Fort Collins, CO. After she brought her twin boys home in 2016, “I woke up and there was blood pouring out of me,” she recalls. “I felt like I was going to bleed out.” She was readmitted to the hospital, where she was treated for a uterine infection and underwent a dilation and curettage to help clear the blood clots from her uterus. “It felt like an eternity,” she remembers of those days spent apart from her newborns while she grappled with her mortality — the trauma of which she says she still deals with five years later.

It doesn’t have to be this way. The CDC indicates that two out of three pregnancy-related deaths are entirely preventable, yet newly released data shows that rates in the U.S. surged another 15% from 2018 through 2019. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, involving both disruptions to health care access and increased risk of serious illness for pregnant moms, has yet to be measured, but preliminary data shows that it only made things worse.

The reason for the continuing growth in death rates boils down to this: While the subject of maternal mortality has historically been ignored from a legislative and/or health care reform standpoint, the major contributing factors to it continue to trend upward. The box at left explains some of those factors — including the fertility treatments that may have contributed to my first ordeal.

DANGEROUS DELIVERIES: MAJOR FACTORS THAT PUT MOM AT RISK

WOMEN BEGINNING THEIR PREGNANCIES LESS HEALTHY. With national rates of conditions like diabetes and heart disease on the increase, research points to a correlation between these preexisting conditions and poor outcomes.

TOO MANY C-SECTIONS. Almost one-third of U.S. births are via C-section, far more than the World Health Organization recommends. A C-section is major abdominal surgery, and potential complications include blood loss or, as in my case, blood clots. Among the possible driving factors for nonessential cesareans: The Atlantic reports that doctors can charge about 15% more for a C-section than for a vaginal birth.

OLDER WOMEN HAVING BABIES. The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) says women over 35, like me, are one and a half times as likely to experience serious pregnancy complications. The most recent data shows that the death rates for women 40 and above are six times as high as those for women under 25.

MORE FERTILITY TREATMENTS. Along with the potential for increased comorbidities for older moms, the parallel trend of more women using assisted reproductive technologies to become pregnant may be contributing to the increase.

MY PREGNANCY JOURNEY

I first started trying to get pregnant at 35. After nearly two years with no luck, I consulted with a fertility specialist and was prescribed the typical course of fertility drugs, including clomiphene citrate (ovulation-inducing pills) and injectable hormones (gonadotropins).

I did get pregnant, but a routine ultrasound showed the pregnancy to be ectopic, meaning the embryo was growing outside the uterus. Within hours, I underwent an emergency laparoscopic surgery requiring the removal of my right fallopian tube as well as the embryo. That day in September 2016, I learned the difference between mere crying and weeping.

Ectopic pregnancy is the leading cause of death for pregnant women in their first trimester. What I wasn’t told at the time is that one case-control study linked each of the fertility drugs I was prescribed with as much as a fourfold increase in the risk of ectopic pregnancy. Being a woman over 35 is one risk factor.

Natalie Dayan, M.D., director of obstetrical medicine at McGill University Health Centre in Montreal, Canada, worked on a separate 2019 Canadian study that linked heightened maternal risks with infertility treatments. The likelihood of severe maternal complication, she says, was about 1.4 times higher in women who used infertility treatments compared with that for those who didn’t, and she adds that doctors should use “extra caution and surveillance” for pregnant women who have undergone infertility treatment.

WHO’S AT GREATEST RISK?

Overall, women in rural areas face the most danger, according to the HHS, in part because these communities have experienced a significant decrease in access to hospitals with obstetric services over the past two decades. A 2020 report from the nonprofit advocacy group March of Dimes found that 7 million American women of childbearing age lived in maternity care deserts. This includes women of all races. But there appears to be no group at greater risk than people of color. Government data has tied the disparities to a variety of circumstances, including unequal access to care and this group’s greater tendency to have certain underlying health conditions. Experts say that above all, the poorer outcomes are driven by institutionalized racism extending into the health care system.

Rep. Underwood, who is also a registered nurse, notes that among maternity care providers, “we see implicit bias and, in some cases, explicit bias — a.k.a. racism.” She adds, “We also see racism at a systemic or structural level throughout our maternity care system and our health system broadly, and rooting that out requires comprehensive solutions."

Mary-Ann Etiebet, M.D., associate vice president for health equity at Merck and lead of Merck for Mothers, an initiative aimed at preventing maternal death worldwide, says that at the most basic level, women, especially women of color, consistently report that their health care providers are simply not listening to them. She cites feedback from pregnant women of color who have “shared experiences of poor communication, dehumanizing care, abandonment and rough treatment — they felt that they were ignored.” She adds that this is “a big driver of the systemic inequity we see around maternal health.”

BRINGING THE HOPE

Dr. Etiebet believes that the time is ripe for change: “We are now moving from just raising awareness of the issue to actually bringing momentum for collective action around solutions.” In December 2020, HHS and the then U.S. Surgeon General laid out a sweeping joint initiative on improving maternal health outcomes in the U.S., incorporating goals of reducing racial disparities. The plan’s main objectives include improving the quality of and access to maternity and postpartum care as well as bolstering data and research efforts. The hope is to cut maternal mortality rates in half by 2025 as well as reduce C-section delivery rates by a quarter within that time frame.

The Biden-Harris administration has promised further action too, anchored on a nationwide expansion of the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative, founded in 2006, which so far has helped halve California’s maternal death rate. In February, congressional members of the Black Maternal Health Caucus introduced the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act of 2021, a 12-pronged legislative package aimed at improving maternal health outcomes while countering related racial inequities. Rep. Underwood, who leads the bill, says that some measures have bipartisan support and are expected to pass quickly: “Saving moms’ lives is something we can all get behind.”

Whatever the path forward, experts see increased access to postpartum health care for everyone as a pillar of reform. A single six-week postpartum checkup remains standard, despite the fact that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists changed its recommendations in 2018 to state that mothers should have an initial checkup within three weeks after delivery. Another proposal is the expansion of midwifery and doula care, which evidence indicates can improve outcomes by lowering rates of C-sections and other medical interventions. But this approach can work only if insurance providers reduce barriers to care. Promisingly, part of the $1.9 trillion stimulus package passed in March provides federal funding to states to expand pregnancy-based Medicaid health coverage (Medicaid finances more than 40% of births nationally). The money pays for postpartum maternal coverage for up to a full year, up from the current two months.

“If I wasn’t on Medicaid and I had to worry about a medical bill, I might have hesitated, and it might have been too late,” says Erickson of her ordeal. “Medicaid saved my life.”

Of course, I hate to tell any expectant mom that things can go terribly wrong. But until we advocate for real change, things won’t get any safer for mothers. My daughter is now almost 4 — a wondrous little creature who, for me, is such a marvel to behold that my heart spills over with gratitude for her. But I’ve buried the haunting trauma — how I walked through the depths of Hades, twice, to have her. I can only hope that necessary policy changes are enacted to spare future mothers — including, perhaps, my own daughter one day — such devastating journeys to the underworld. Because it’s painfully clear that not all of us make it back.

You Might Also Like