Praise for the ‘Great Agnostic’: 19th-century defender of free thought brought ideas to Stockton

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Earlier this year, I documented the ongoing moral prejudice against religious non-believers and explained how living a moral life does not require belief in a supernatural deity or a commitment to organized religion.

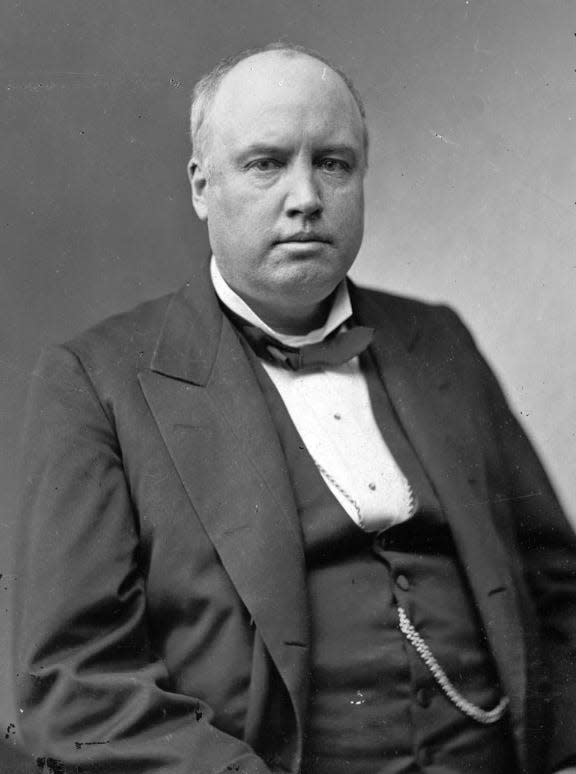

One of the pioneering exemplars of a non-religious or secular moral life in the U.S. was Robert Ingersoll, a late 19th-century religious agnostic who is regrettably little-known today. In his lifetime, Ingersoll was the most sought-after political orator for the Republican party and became the most famous defender of free thought and agnosticism. He spoke all over the U.S. to large crowds, including three times in Stockton. In 1877, he gave his celebrated lectures "The Liberty of Man, Woman and Child' and 'Ghosts' " at the Stockton Theater, which were advertised, and reported on, by the Stockton Daily Independent.

When Ingersoll died in 1899, the Stockton Daily Record published a laudatory eulogy, stating that his ‘example in the matter of virtue can well stand comparison with those of most if not all of the professional teachers of religion ... his influence on the churches has been for their good. Its effect has been to liberalize them ... [he] was, in short, one of the noblest men the world has ever produced...this age does not fully appreciate Ingersoll, but as the religion of superstition and impulse and passion gives way and the religion of intelligence, of love and justice is developed, he will be appreciated as a hero.’

Why would this religious infidel be seen as heroic?

Col. Ingersoll was an abolitionist who formed his own regiment to defend the Union at the outbreak of the Civil War. He was a lawyer who argued before the Supreme Court. He had the courage to speak all over the country to promote scientific and critical thinking and to dispel superstitions and ignorance that stemmed from the Bible, especially from the new form of fundamentalist Christianity. He was a loving father and husband who said ‘he who builds a home erects the holiest altar beneath the stars.’

Ingersoll was also outspoken on vital social and political issues, issues that are still divisive today. Here are Ingersoll’s own words about some of them.

Racial equality. A friend of Frederick Douglass, Ingersoll objected to an infamous 1883 Supreme Court case that overturned the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which outlawed racial discrimination in public housing and transportation. He said, ‘it leaves the best of the colored race at the mercy of the meanest of the white. It feeds fat the ancient grudge that vicious ignorance bears toward race and color. It will be approved and quoted by hundreds of thousands of unjust men…The men who, by mob violence, prevent the negro from depositing his ballot.’

Women’s rights. A friend of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Ingersoll defended the equality of women, including their bodily autonomy and right to determine whether to become a mother or not. ‘In my judgment, the woman is the equal of the man. She has all the rights…if there is any man I detest, it is the man who thinks he is head of the family.’

Ingersoll had a simple philosophy of life:

My creed is this: Happiness is the only good. The way to be happy is to make others happy...that man is happiest who is nearest just—who is truthful, merciful, and intelligent...The time to be happy is now, and the place to be happy is here.

Ingersoll elaborated on his credo in a later writing, expressing a secular moral worldview that he steadfastly maintained was an intellectual and moral improvement over supernatural monotheistic religions:

to love justice, to long for the right, to love mercy, to pity the suffering, to assist the weak, to forget wrongs and remember benefits — to love the truth, to be sincere, to utter honest words, to love liberty, to wage relentless war against slavery in all of its forms, to love wife and child and friend, to make a happy home, to love the beautiful…to cultivate courage and cheerfulness, to make others happy, to fill life with the splendor of generous acts, the warmth of loving words, to discard error, to destroy prejudice, to receive new truths with gladness, to cultivate hope, to see the calm beyond the storm, the dawn beyond the night, to do the best that can be done and then to be resigned—this is the religion of reason, the creed of science. This satisfies the brain and heart.

Amen.

Lou Matz is an aging basketball player and professor of philosophy at University of the Pacific.

This article originally appeared on The Record: Praise for Robert Ingersoll, an early agnostic