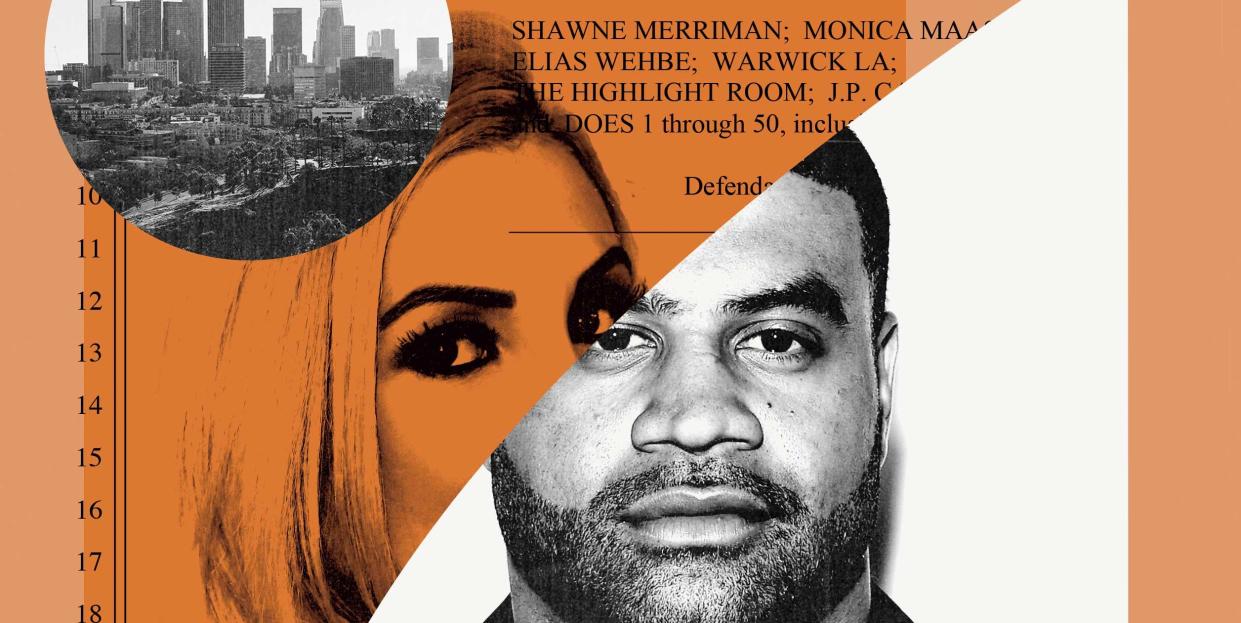

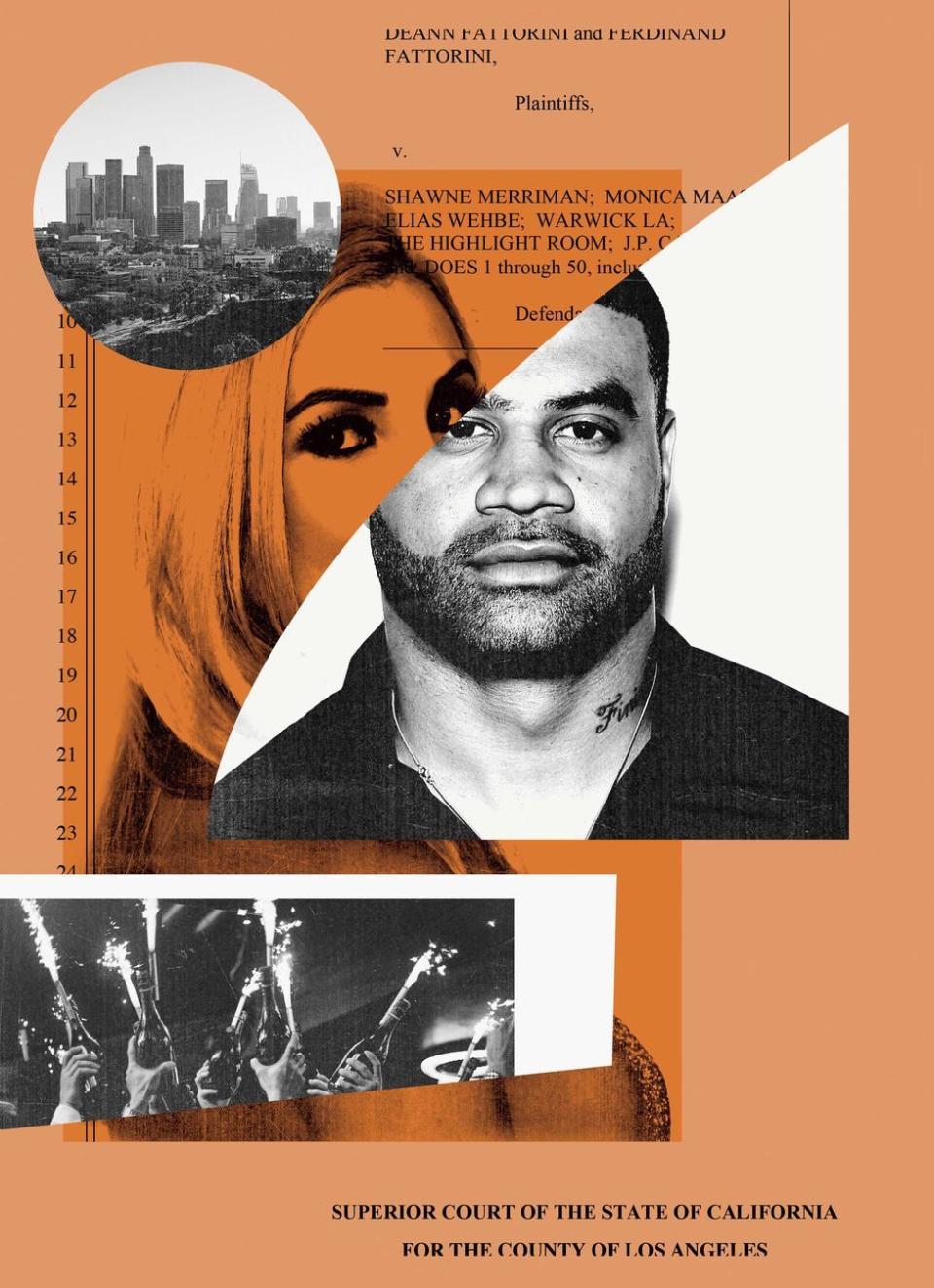

Police Assume She Died of an Accidental Overdose. But What Really Happened After She Left the Club?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It was a tragically beautiful day to die in West Hollywood. The summer sky was Technicolor blue, and palm fronds undulated in the breeze outside the low-rise 1960s apartment block where 30-year-old Kimberly Fattorini, a Playboy casting associate and part-time model, was drawing her last breaths on a friend’s couch. At some point between 10:30 a.m. and 3:30 p.m. on Friday, July 21, 2017, she slipped from chemical oblivion into eternal slumber.

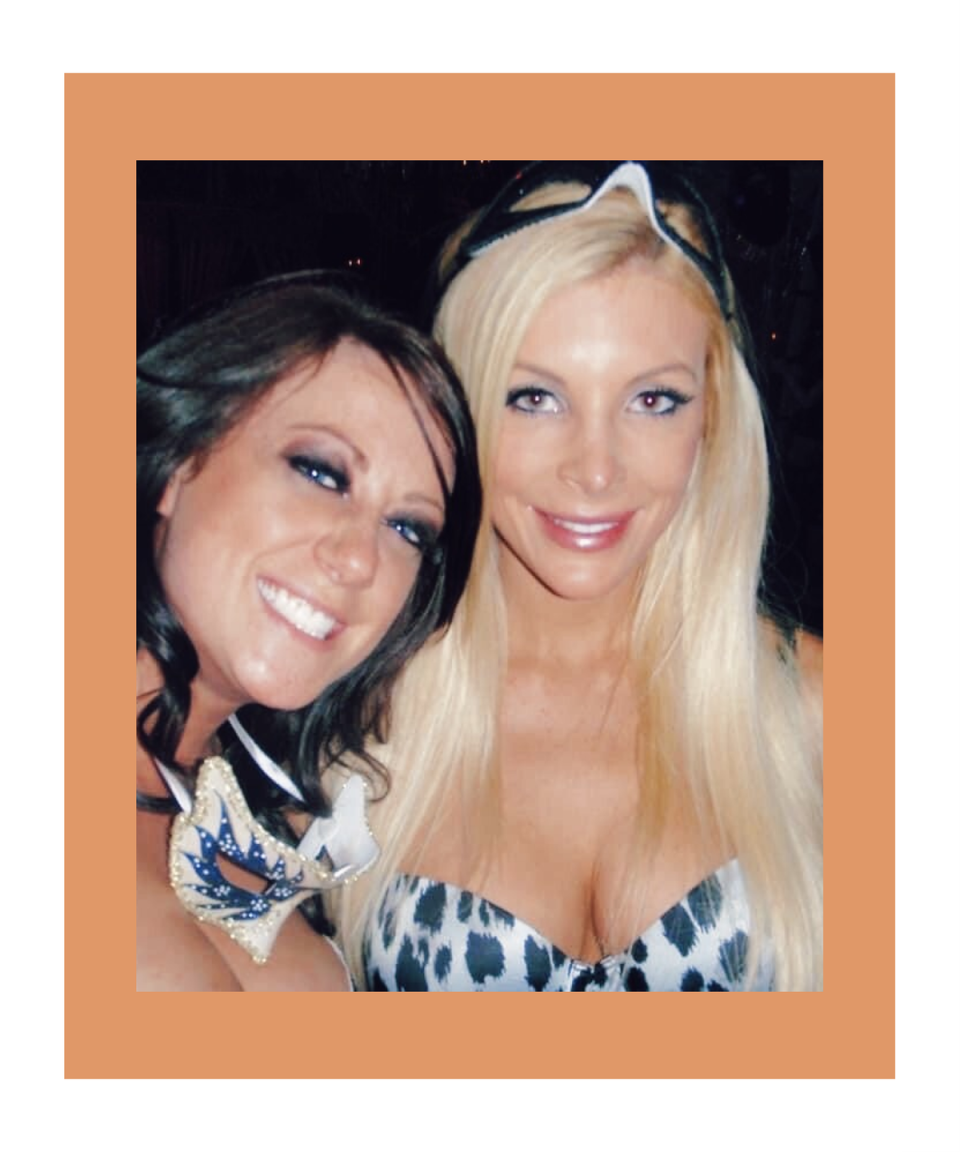

Even before the toxicology report was complete, word spread that Fattorini had overdosed. She had spent the previous night at a new club called The Highlight Room with her friend Monica Maass, a Playboy model. Maass told an investigator from the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department (LASD) the two women had been out all night drinking and doing cocaine before returning to Maass’s apartment at 5 a.m., where Fattorini had fallen asleep. At about 3:15 p.m. Maass realized Fattorini wasn’t breathing and called 911.

Maass’s initial recollection of events would eventually be contradicted by text messages found on Fattorini’s and other people’s cell phones, according to allegations in a wrongful death lawsuit filed in July 2019 by Fattorini’s grieving parents. But that Friday afternoon, as the investigator surveyed both the body and the apartment, he found no reason to suspect foul play. Neither did the coroner, who ruled Fattorini’s death an accident, despite the bruises on her legs and gamma hydroxybutyrate—better known as the date rape drug GHB—in her system. On the face of it, Fattorini was just another unlucky blonde who lived too fast and died too young in Hollywood. Until, that is, earlier this year, when her parents’ lawsuit surfaced on social media, putting forth a different and decidedly more sinister version of events, one that shines an uncomfortably bright light on the excesses of the shady Hollywood club scene and the danger that lies beyond the velvet ropes.

The Fattorinis’ lawsuit claims that sometime after The Highlight Room closed at 2 a.m. on July 21, Fattorini, Maass, and a third Playboy model named Stefanie were invited to the home of a notorious nightclub promoter named Eli Wehbe. The lawsuit also alleges that unbeknown to the three women, Wehbe had “assigned” each of them to himself and his two buddies: a car dealer named J. P. Castro and former NFL linebacker Shawne Merriman.

According to a series of text messages attached to the complaint, while Fattorini and her friends were partying at Wehbe’s house in the early hours of Friday morning, Wehbe was texting Castro to say he was entertaining a group of women who were “hot as fuck” and telling him to bring chasers. “Only one is weak putting her to sleep tho,” Wehbe added. “Coke dealer can bang her. He gets the scum.” A few hours later, Wehbe texted Merriman: “Got 3 whores over. I’m tryna get rid of them so I can smash [Stefanie].” (Smash meaning “have sex with.”) “Aight, I can come and take them,” Merriman replied, referring to Fattorini and Maass. Merriman, who was 20 minutes away, told Wehbe he planned to take Fattorini to a hotel “if she’s down.” “If she’s not I can chill here idc [I don’t care],” he added. “Not in the mood for games.”

Merriman arrived at Wehbe’s house between 8:30 and 9 a.m., allegedly clutching a bottle “filled with a liquid.” Shortly afterward, Fattorini sent Wehbe the following messages:

“But Your friend just poor’d half G in my drink [“G” meaning GHB]

And I have never

Don’t go to sleep come Check on mr llllllllllllqlqllqllll

Me when you can”

In a statement posted on his website after Fattorini’s parents’ lawsuit surfaced earlier this year, Wehbe claimed that after receiving her texts, he checked Fattorini “was okay” and that when he walked her, Merriman, Castro, and Maass to the front door to say goodbye a short time later, “everyone appeared in good spirits and in good shape.” However, the lawsuit—which names Wehbe, Merriman, Castro, Maass, The Highlight Room, and another nightclub called Warwick as defendants—suggests that Fattorini was so out of it at Wehbe’s house she didn’t even realize she and Merriman were still in the same building.

When the football player, who was downstairs, repeatedly texted Fattorini to ask for her address (“I’ll call a car for us,” he offered), she kept responding “Where r u” interspersed with gibberish such as “No dgtvr nnmmmmmmmmo” before sending him a screenshot of Wehbe’s house on a map. At around 10:09 a.m., Merriman ordered an Uber to take him, Fattorini, Maass, and Castro back to Maass’s apartment, where, according to the complaint, Maass invited everyone inside for a drink.

By the time paramedics arrived five hours later, Merriman and Castro were gone, and Fattorini was lying on the living room floor. According to the lawsuit, her lips were blue, her bra was twisted, and her jeans were “unzipped and unbuttoned.” She was pronounced dead at 3:30 p.m.

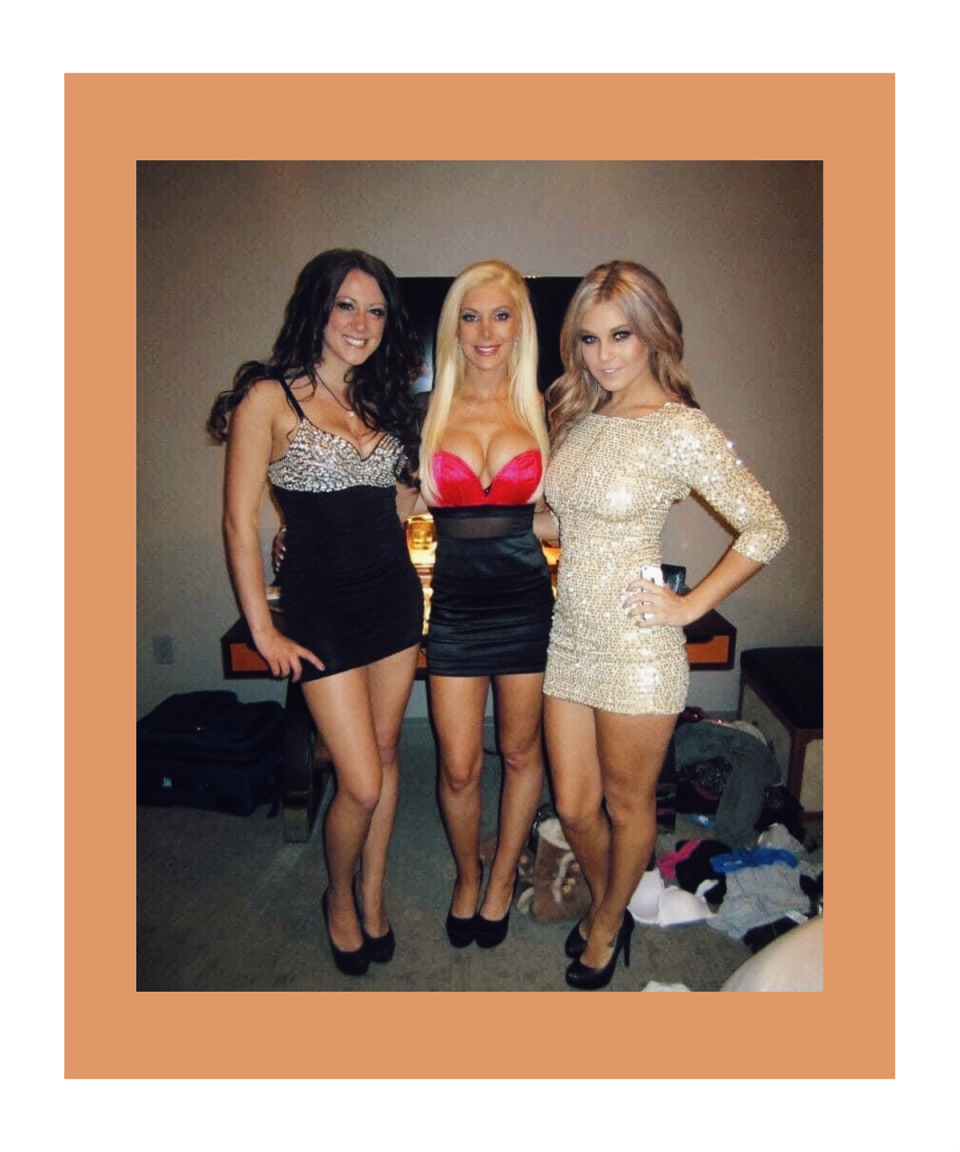

Kimberly Fattorini was blonde and beautiful, with a cool job and a significant Instagram presence (over 150,000 followers). Her life resembled a sizzle reel of mid-2000s chick flicks: The House Bunny meets Legally Blonde, with a touch of Mean Girls, remastered for the social media age. She was always immaculately groomed: her butter-yellow tresses elegantly coiffed, nails polished, eyelashes expertly glued on. Even at 6 a.m., when she arrived at Playboy Plus, Playboy’s broadcast and digital arm, to oversee casting for The Playboy Morning Show, she looked “perfect,” recalls Tricia Cruz, a sound engineer. “I would sit there and go, How did she do it?”

Before arriving in Hollywood, Fattorini completed a double major in business administration and economics at Whittier College in Whittier, California, where in 2009 she was honored as an “Outstanding Student.” She dressed the part, too. For the office, she favored “the cutest little business outfits,” says model Lola Palermo.

In addition to her desk job at Playboy Plus, Fattorini would step in front of the camera, starring in a Playboy TV segment called “What a Girl Wants: Bedroom Etiquette,” or would appear as a guest on Playboy Radio. If her father, Ferdinand, a senior vice president at Sony Pictures, and mom, DeAnn, had reservations about Fattorini’s career, they didn’t tell her, according to Cruz. Fattorini once tweeted about DeAnn meeting her for lunch at work. (Ferdinand and DeAnn declined to be interviewed.)

Until shortly before her death, Fattorini was also in a long-term relationship with fellow casting director Sam Rhima. At one point the couple were so close—some described them as “codependent”—that as well as living together, they shared a desk at Playboy Plus. At nightclubs or on red carpets, the duo would often be flanked by an entourage of models. “All the girls would look up to Kimmy,” says Fattorini’s friend Carrie Overgaard. “And a lot of the girls would have crushes on Kimmy.”

Like everything in Hollywood, however, life wasn’t always as glossy as it appeared onscreen. What Fattorini really wanted was to be a Playboy centerfold. In her downtime, she burnished her portfolio, posing for men’s magazines like Maxim and FHM Thailand, but with each passing year, her chances grew slimmer, especially after she turned 30 in October 2016. By then, Playboy was also in crisis, buffeted by the triple threat of falling circulation, the burgeoning #MeToo movement, and founder Hugh Hefner’s failing health. “We saw the writing on the wall,” Cruz recalls. “Everybody was told to start looking for other jobs.”

Cracks had also begun to appear in Fattorini and Rhima’s relationship. “She wanted to have a baby and get a house,” says friend Jennifer Riley. “She was growing up.” However, Rhima, a Hefner wannabe, apparently wasn’t ready to settle down. According to Riley, sometime after her thirtieth birthday, Fattorini broke things off, although friends suspected the couple would get back together. At her funeral, Rhima gave a eulogy lamenting that they would never get the chance to wed. “I think he had a lot of guilt about that,” Palermo says. (Rhima declined to be interviewed.)

In the aftermath of the breakup, Fattorini moved in with a friend and began partying even more. But few of the pressures weighing on Fattorini in early 2017 were evident to her social media followers, who were only exposed to the highlights: a pool party on Sunset Boulevard; walking the runway at a fashion show; dancing at a nightclub. “When she started to have problems with Sam, she started to go out a lot more and was doing more drugs,” says a model who shared a close friend with Fattorini and spoke on condition of anonymity. “Her life was just spiraling, you know, inside. No one saw it from the outside.”

If Fattorini represented the aspirational, PG face of L.A.’s clubland, Eli Wehbe was the R-rated version. Until April, when the Fattorinis’ lawsuit was made public, Wehbe, who’s tall, with dark eyes, chiseled cheekbones, and tattoo sleeves, was considered the king of clubs. His profession—and the middle finger he often held aloft in photos—belied a devout family, who lived an hour away. “Loving my brother requires patience, understanding, and walking with him though we are incredibly different people,” his sister Diana, a Christian motivational speaker, wrote in a Facebook post contemplating the Catholic meaning of family.

Wehbe’s fiefdom was a hot spot called Warwick, where he was a partner and often butted heads with his colleagues. “He wasn’t very gracious,” says Kelsi Kitchener, cofounder of event company VIPER by KCH, who worked alongside Wehbe at the club: “You’d be hard pressed to find someone who would say, like, ‘Eli is such a great, nice, kind guy.’ ” Kirstina Colonna, who used to work as a bottle server at Warwick, says Wehbe was once so rude to her she threw a tray of drinks at him. “He’s the kind of guy, if you’re not gonna play his game, he’s not gonna be nice to you. And so he wasn’t nice to me,” she says. “And to be fair, I wasn’t very nice to him either.”

It’s unclear how Fattorini met Wehbe—the lawsuit claims it was a month or two before her death—but they had long operated in the same orbit. Wehbe was adept at cultivating strategic relationships with celebrities such as Paris Hilton, Brody Jenner, G-Eazy, and the so-called King of Instagram, Dan Bilzerian, a friend of Fattorini’s. “His clientele was a lot of influencers, YouTubers, CW actors, athletes,” Kitchener says.

According to the lawsuit, after meeting Fattorini, Wehbe began plying her with invitations to Warwick. “He definitely paid attention to her,” Riley says. For Fattorini, just out of an intense seven-year relationship, Wehbe’s solicitations no doubt represented an opportunity to let loose and, perhaps, make Rhima jealous. What Fattorini may not have realized was that in the dimly lit world of Hollywood nightclubs, she was vulnerable—especially if, as her parents allege in the lawsuit, Wehbe was lavishing alcohol and drugs on her. “He would also offer and urge everyone, including Kimberly, to use cocaine and party with him around his VIP network until the sun came up,” the Fattorinis’ complaint claims. “It was the nature of his business. He was bringing the women to get the VIPs and bring them together at his clubs. He would push drugs and after-parties in order to keep the experience going for the VIPs, thereby ensuring repeat business for the clubs, an extension of his network, profit, and a rise in the ranks.”

In July 2017, The Highlight Room opened on the roof of the Dream Hollywood hotel, and Wehbe started promoting Thursday nights there. That summer, the club was the place to be seen in L.A. Even before its launch, it was attracting marquee names like Calvin Harris and Lana Del Rey. So although Fattorini was due to go on vacation with her parents the following day (clothes and a suitcase were found laid out in her apartment after her death), Wehbe’s invitation to the grand opening on July 20 was presumably a no-brainer.

Because her trip meant she’d also be missing Maass’s birthday party that weekend, Fattorini suggested that Maass join her at the opening. The women, who’d met at a Playboy Plus casting some five years earlier, were close, vacationing in Hawaii and Las Vegas and celebrating holidays together. “Kim viewed her and trusted her as a friend,” Tawnie Jaclyn, Fattorini’s roommate, wrote on Instagram.

The lawsuit is silent about what exactly took place between the group arriving at Maass’s apartment and the 911 call, but it alleges that Merriman was still present when Maass spoke to the operator—that, in fact, he was the one who moved Fattorini from the couch onto the floor at the 911 operator’s request—and that when the operator instructed Maass to begin CPR, she replied: “I’m not gonna do that. I don’t want to touch her.”

In her initial statement to the investigator, Maass claimed that she and Fattorini arrived at her apartment at 5 a.m. and went to sleep (according to the text messages attached to the complaint, they were actually at or on their way to Wehbe’s house at that time) and failed to mention that both Castro and Merriman had been present. “Foul play is not suspected,” the deputy coroner wrote in his initial report, in which he also recorded Maass’s version of events. It was this assumption, the Fattorinis claim, that led to the coroner failing to perform a sexual assault exam; by the time an LASD detective requested one, “in light of additional information he had received,” it was no longer possible.

Two hours after calling 911—and with Fattorini’s body still sprawled across her living room floor, awaiting removal by the coroner—Maass went to meet up with Merriman. According to the complaint, even Wehbe was surprised the duo had reconvened that evening, replying “Wtf” when Merriman told him via text.

No one has ever been arrested in connection with Fattorini’s death. According to Lieutenant Robert Westphal of the L.A. Sheriff’s homicide bureau, the case was closed in September 2017, two months after she died. “The coroner’s office ruled the cause of death an accident, so based on that, and no other evidence that would support any other conclusion, we’re no longer investigating,” he told ELLE. “I’m sure every possible clue or lead would have been investigated before this conclusion was reached.”

In the absence of any criminal proceedings, whispers have inevitably surfaced that Fattorini’s parents, blindsided by their daughter’s drug use, are simply looking for someone to blame. “Her parents—plaintiffs in this action—understandably are searching for answers,” Wehbe points out in a court-filed response to the lawsuit, in which he seeks to be dismissed as a defendant due to the “vague and uncertain” claims against him, among other grounds.

Although the lawsuit points to the high levels of GHB in Fattorini’s blood, a spokesperson for the coroner’s office stresses that it wasn’t the GHB alone that killed her: “All three of the drugs [cocaine, alcohol, and GHB] were contributing factors in her death.” Similarly, the bruises on her legs may have been self-inflicted (“I have bruises on my legs too!” Fattorini once tweeted a friend. “Haha. Guess we had a good time”). And the coroner’s failure to conduct a rape exam may have been influenced as much by the “appropriately positioned” tampon found inside Fattorini’s vagina as Maass’s statements.

In May 2020, Maass filed her response to the lawsuit, claiming the Fattorinis’ selective choice of texts and other “electronic communications” from that night “has created a false narrative, has led to unwarranted speculation, conjecture, and has unfairly and dangerously placed the defendant in a patently false light.” An ex-roommate, with whom she fell out last year, tells ELLE that Maass’s version of events is “plausible” based on her hard-partying lifestyle. “The story of [how] she didn’t find [Fattorini] until the next afternoon was very possible,” says the roommate, explaining it wasn’t unusual for Maass to sleep in until 4 p.m. after a late night out.

Maass and Merriman, who share a lawyer, declined ELLE’s requests for an interview, as did Wehbe and Castro. However, in the statement posted to his website, Wehbe wrote, “I want to make it very clear that I did not give any illegal substances to Kim,” and apologized for the “inappropriate, hurtful, and disrespectful” text messages he sent that night. A spokesperson for Tao Group Hospitality, which owns The Highlight Room, tells ELLE via email: “Our highest priority is to provide a safe environment for all our guests. We are saddened by Kimberly’s passing and would always cooperate with law enforcement in any such matter, but have not been contacted regarding these allegations.”

In April, after the Fattorinis’ lawsuit went viral on social media, a petition titled “Remove Eli Wehbe as partner from Warwick L.A. and all other nightlife establishments” appeared online. Warwick (which declined to comment) released a vague statement on Instagram Stories distancing itself from Wehbe: “A lawsuit regarding this incident has named an associate of our establishment. We have since ended our relationship with this individual.” A spokesperson for Tao tells ELLE that Wehbe “ceased working as an independent contractor for The Highlight Room well before these allegations came to light.”

Following the outcry online prompted by the lawsuit, the women of clubland are pushing for reform, led by the female-fronted event company VIPER by KCH. In July, VIPER launched a nightlife safety initiative backed by some of L.A.’s hippest clubs—including both Warwick and Tao—which includes sexual harassment training for staff, renewed efforts to counteract drug use, and the establishment of an advisory board for the industry. Although any change will come too late for their daughter, there is hope that the Fattorinis’ lawsuit, which is due to be heard in January 2021, will make nightclubs safer places for the women who continue to work and play there.

What is perhaps most revealing about Fattorini’s death is that she was no ingenue. Yet despite being a veteran of Hollywood nightlife, she still ended up as its victim. “What happened to that poor girl Kim could have happened to literally anyone,” Kirstina Colonna says. “It’s just that she was the unfortunate one.”

This story appears in the November 2020 issue.

You Might Also Like