Adrienne Kennedy Will Always Tell Stories

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When I was young and obsessed with the challenges that come with living a creative life, there was only one writer who did the kind of work I wanted to do: the playwright Adrienne Kennedy.

I first encountered Kennedy’s work in a Black theater class in college where we read one of her early plays: Funnyhouse of a Negro, alongside Amiri Baraka’s Dutchman. Both works depict how racial violence might be veiled by the rhetoric of assimilation. Kennedy’s plays highlight experiences that had not yet been valorized by dramatic action. No one else captures the absurd and uniquely American ways that racial tensions can impinge on one’s sense of personal security, masterfully depicting characters in moments of crimping suspension, caught in the pinch between frustration and rage, where one tries to decipher if they are powerful or powerless.

Kennedy is now 91 years old, and her work is, at long last, showing on Broadway. A brand-new production of Ohio State Murders opened in New York in December and has its last performance this Sunday, January 15. It is directed by Kenny Leon and stars six-time Tony Award winner Audra McDonald in a virtuosic performance. Ohio State Murders took Kennedy nearly 20 years to complete.

Upon this milestone, I want to know which piece in Kennedy’s body of work she is most proud of. Her answer is more nuanced than my question allows. Writing through email, she tells me, “I would never use the word proud to connect to my writing. In spite of me, it comes out of long periods of bleak thinking. I struggle with several attempts for long times.” It would not surprise me to hear a similar response from the main character of Ohio State Murders, a playwright named Suzanne Alexander, who resembles Kennedy in many ways. In previous productions, two actors play the role of Suzanne—one of them young and another in middle age—but McDonald wields a unified character with great intensity in this production, where the playwright is both onstage and behind the story.

Ohio State Murders opens in a perfectly anodyne way, with Suzanne delivering a guest lecture. She says, “I was asked to talk about the violent imagery in my work; bloodied heads, severed limbs, dead father, dead Nazis, dying Jesus.” Her focus quickly shifts to her time as one of a few Black students on the campus of Ohio State in the late 1940s, along with the strong feelings that are awakened in her by the literature she reads in her courses. At first, these themes appear to be disconnected, but the path between them is drawn like footprints in snowstorm, each step a hollow that also gathers the cold like a basin.

In other plays like She Talks to Beethoven and Sleep Deprivation Chamber, a collaboration with her son Adam Kennedy, the action usually takes place in an atmosphere of fear and suspicion. At times, Kennedy’s characters are bolstered through references to icons from literature and music as imagined places become real. In some of her plays, Kennedy brings these figures to life onstage. In A Movie Star Has to Star in Black and White, figures from Hollywood’s Golden Age such as Bette Davis and Shelley Winters reenact key performances, and amplify the emotional state of characters of Kennedy’s own invention as her protagonists work through their intimate dramas.

In a New York Times profile on Kennedy published in 2018, Yale professor Daphne Brooks proclaimed that Kennedy’s plays “brought to life the depths of black female interiority and the aching humanity of black womanhood.” And long before Hamilton’s color-blind casting, Kennedy’s Funnyhouse challenged the visual imaginations of readers and audiences by creating racially composite characters who show how one’s ancestors might manifest as antagonists.

Kennedy’s plays embrace abstract characters, perhaps because they often engage abstract concepts, such as racial identity. The works are as much focused on ideas as they are on action. Like other playwrights who used abstract expression to amplify the emotional weight of daily injustices—Ibsen, Chekhov, Beckett, and Fornes—Kennedy stands as one of the greatest practitioners of abstract drama, ever.

In many of Kennedy’s plays—but not in all of them; I do want to be clear about that—Black women struggle with their creative ambition and the elusiveness of success. I have been most affected by Kennedy’s plays that depict creative Black women attempting to write in an atmosphere where there is a symbolic or realistic threat to her children. In the years following the killings of Tamir Rice, Trayvon Martin, Renisha McBride, and Michael Brown, among a devastating list of others, these works have become portentous of the kind of experiences too many Black mothers share.

But in the post-Obama years—which have brought both recognition of these dynamics and a crescendo of recognition and support for Black literature, drama, television, and film—Kennedy still has not been given the kind of acknowledgment she deserves. Prompted by this frustration, years ago, I decided in my own short fiction to testify to her influence. As an homage, I wrote Kennedy into a story about my struggles as a writer—Kennedy walking into my scene just as Shelley Winters walked into hers. It opens at a diner, where my protagonist attempts to interview Kennedy, who deflects all questions. When she departs, her enigmatic presence lingers. I didn’t want to publish the piece without her permission. So with the help of my friend Margo Jefferson, I sent it to Kennedy. To my surprise and delight, she agreed to its publication. Her consent was also a nod of encouragement that serves as an affirmation to this day.

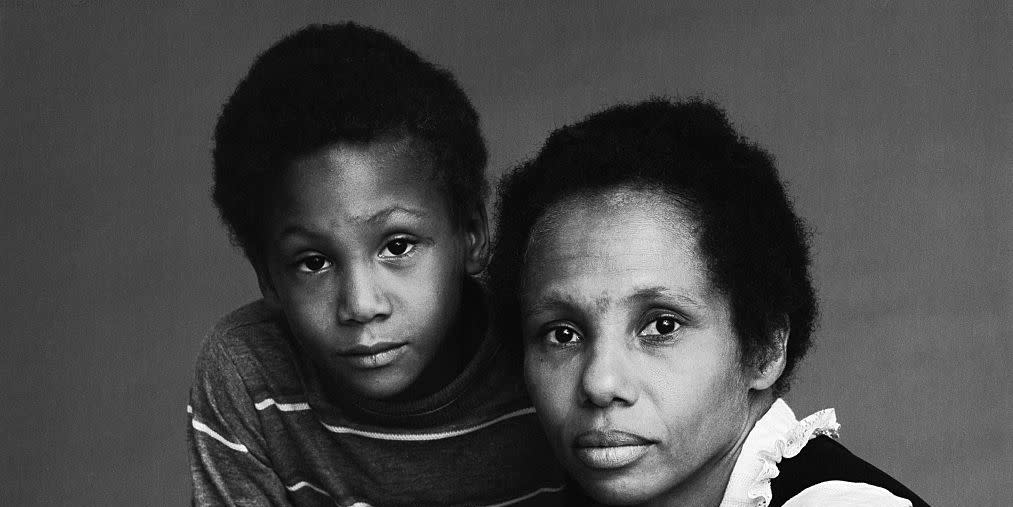

More accolades for Kennedy have come in recently. In 2021, she received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Dramatists Guild of America. This year, she was awarded the Gold Medal for Drama from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. These acknowledgments, along with the new Broadway show, however, do not mean that Kennedy’s work is done. She notes that one of the things she still hopes to write about are her children Adam and Joe Jr.’s childhoods, “which were both exhausting and enchanting.”

She also wants to write about her divorce from her ex-husband, Joe Kennedy, which along with struggles in her writing life made for a very difficult time. Her time with her children, however, served as counterpoint to other worries, and her connection with them allowed her to withstand the vicissitudes of a public, creative, and political life. She still has stories to tell about “successes and failures, and often how I sought comfort from their faces. Raising children as a light from the worries about my career.” For Kennedy and for us, these are plots yet to be written.

You Might Also Like