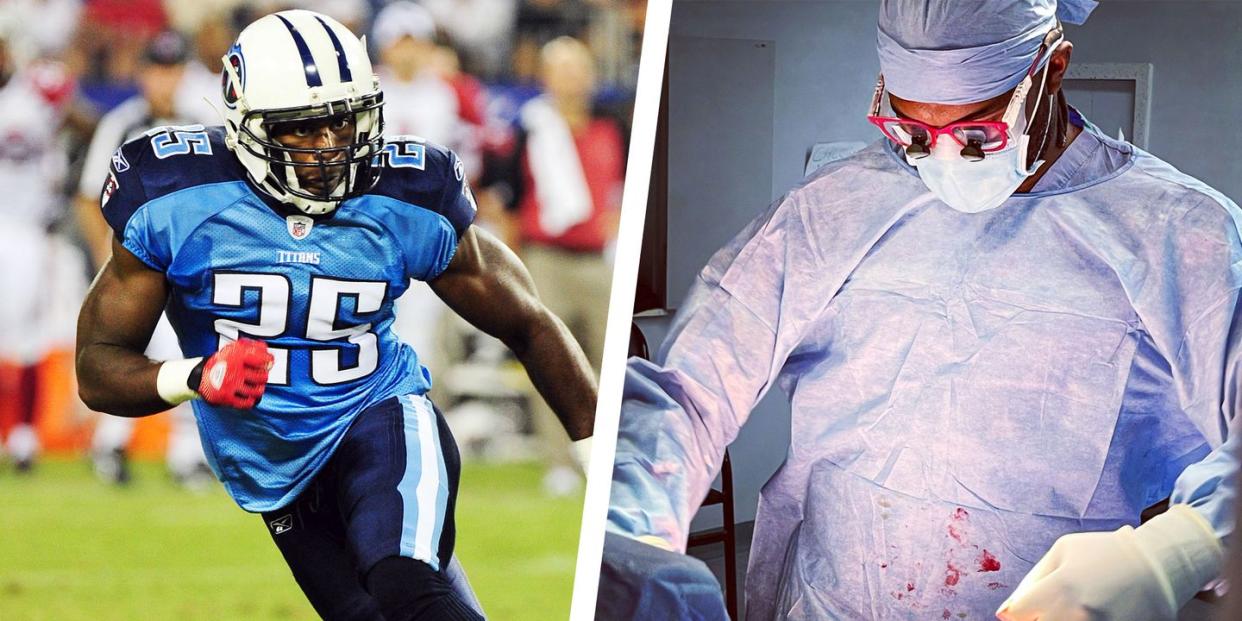

The Playbook That Helped Myron Rolle Transition from NFL Player to Neurosurgeon

BANGING HEADS and fixing heads might seem like totally different pursuits, but Myron L. Rolle, M.D., says that doing the one prepared him to do the other. Football “has given me so much. Friends, fitness, focus, and the intangibles: communication, teamwork, structure, discipline, and overcoming adversity."

As he details in his new book, The 2% Way, Dr. Rolle was a standout safety at Florida State University, but instead of playing his senior year, he went to Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar. He returned a year later, was drafted in the sixth round in 2010, and played three years in the NFL until he was cut by the Pittsburgh Steelers. After that, he put his energy into studying for the MCAT, which took him to Florida State University College of Medicine and eventually to a residency at Harvard-Massachusetts General Hospital. Many of the processes and mental skills that helped him find success in football prepared him to excel in the OR.

Dr. Rolle is Zooming from the sunny Bahamas, but there’s no sand between his toes. Currently a senior neurosurgery resident and the global neurosurgery fellow at Harvard-Massachusetts General Hospital, he’s spent the past nine months on a medical mission to improve care in low-resource settings. That involved performing surgeries at Princess Margaret Hospital in Nassau, as well as working on policy, training, and education and doing whatever he could to help elevate neurosurgical treatment in the Bahamas, especially for people who face systemic barriers to care. In 2010, his aunt Annie Smith, a native Bahamian, was hit by a car while walking and died from a traumatic brain injury. “My auntie did not see a neurosurgeon for seven hours,” says Dr. Rolle, 35. “No MRI, no CT scans, no diagnostic work, and she died without any medical care. That moment encouraged and motivated me to want to do something.”

It’s what Dr. Rolle does: try to make a difference. He follows his philosophy of seeking small improvements in all aspects of life, including his mental fitness, and it’s helped him with everything from dealing with hate-spewing patients and tricky surgeries to managing stress and disappointment. These are some of the key tactics that have worked for Dr. Rolle.

CELEBRATE THE SMALL WINS

DR. ROLLE learned one of the most important mental skills from FSU coach Mickey Andrews (who learned it from legendary Alabama coach Paul “Bear” Bryant). He’d shout, “‘Myron, 2 percent better on your backpedal, 2 percent!’ It’s about taking very small steps of improvement daily towards a bigger goal that sometimes seems overwhelming,” he says. “You break it down piece by piece and have those small victories that empower you and motivate you.” It also requires a sense of vulnerability, being able to recognize and acknowledge your own weaknesses so you can improve. Dr. Rolle applied the 2 percent way to both his physical training (whether focusing on his first step or his vertical leap) and med school (getting extra practice tying sutures and studying obscure cases). He even applies it in his personal life, recently making an effort to be more punctual and to call his parents more often, micro adjustments that help him incrementally become a better version of himself.

USE FAILURE TO STOKE MOTIVATION

PLAYING IN the NFL is an experience Dr. Rolle calls his biggest failure. “I did everything I could. It didn’t work out [as I wanted it to]. "The NFL is known for Not For Long,” he says, referring to his brief playing career. He retired from the NFL at 26. That experience recharged his desire to go to medical school, a goal he’d harbored since his older brother tossed him, at age 12, a copy of the book Gifted Hands, in which Ben Carson, M.D., describes his journey from child in inner-city Detroit to noted neurosurgeon. A deeply religious man, Dr. Rolle wonders whether having his time cut short in the NFL “was the Lord saying, ‘This is not for you right now, and I’m protecting you from hurting your hand or getting a concussion and not being able to be a neurosurgeon.’ ” He embarked on the six-year journey, all the while using the 2 percent way to find small victories that kept him on track.

HAVE A PLAN AND A BACKUP (AND A BACKUP TO THE BACKUP)

DR. ROLLE’S hands play a major role in his work, having converted from catching interceptions to artfully making people’s brains whole again. At med school, he trained himself to be ambidextrous by using his left hand to write, suture with shoelaces, and perform other knot-tying and stitching drills surgeons do. Dr. Rolle deals with the stress of surgery by spending hours rehearsing his hand movements, visualizing the surgery the same way he prepared for a play on the field. “Because if A and B fail, based on anatomy that I wasn’t expecting, or there’s a bleed or a leak that happens that I wasn’t aware of, what are options C and D?” he asks. “I need to have other plans so that I’m not flustered and paralyzed in the moment. In the shower, I’ll close my eyes and my hands move as if I’m lifting up a part of the tissue using my right hand with a tumor forceps, imagining myself going through it over and over again. I anticipate [extra blood] the same way I anticipated a receiver running an in-route but he runs a hitch or a stop-and-go.” If you’re prepared for contingencies, it’s easier to stay calm.

RELEASE YOUR EMOTIONS TO STAY IN CONTROL

DR. ROLLE must deal with patients with everything from gunshot wounds to the head to cancerous lesions on the brain. Losing a patient is a reality of the job, but he refuses to be jaded and acknowledges that it hurts. “If I ever get to a point that I get so numb by situations that are poor or negative, then I should no longer be a physician,” he says. “I want to feel that pain, because it humanizes the situation and makes me go harder for the next patient and the next family. If we have this blockade about expressing our emotion, it will drive you to dysfunction. You can’t have that when your hands are responsible for lives in the operating room.” When Dr. Rolle lost his first patient, a middle-aged woman with a partially blocked carotid artery, in 2013, he cried all the way home and called his father the next day. He expected his father to tell him to toughen up, but his dad only affirmed his choice of profession, noting his sense of caring and empathy. “I don’t mind a good cry, especially in spaces where I feel comfortable and safe with my brothers, my wife, my parents, my best friends,” he says. “It’s an expression of sorrow, but it’s also an expression that I feel comfortable with you and I can share the emotions that are happening to me. Crying is part of life.”

MAKE IT PERSONAL

BEING A BLACK neurosurgeon amid a white majority brings with it unique challenges. Dr. Rolle recalls how he’s been mistaken for a food-service worker or a member of the cleaning crew, and in one instance a patient’s brother used hate language when referring to him during a preoperative consultation. After discussing it with another surgeon, Dr. Rolle decided to go ahead and perform the surgery, because he wanted to turn a negative (the trauma of a racist insult) into a positive (saving a man’s life). Plus, he was a junior resident at the time and says he needed the surgical hours. In terms of how he focuses during an operation, Dr. Rolle says he thinks of his family. “My wife asked, ‘Myron, how do you get ready for a consult when the doctor calls you at 2:00 a.m. saying there’s someone with a brain bleed in the ER and you’re dead asleep?’ I say, Well, it’s tough. You wake up, wipe the sleep from your eyes, and shake yourself loose. At the same time, if this were my auntie or my mom or someone close to me, I’d want whoever was seeing her or him to be ready, charged up, mind acute, and ready to go. I put myself in that position quite often, and that pushes me to try to be the best I can.”

This story is in the July-August 2022 issue of Men's Health.

You Might Also Like